Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Chasing Things That Cannot Be Chased

Share:

Kameelah Janan Rasheed is a learner—an elastic term that includes artist, writer, teacher, collaborator, and public speaker. In Smooooooooooooooth Operator, a new solo exhibition mounted this fall at the Athenaeum in Athens, GA, Rasheed centers what happens at the margins. Phrases, snippets, footnotes, attributions, and citations collide in an accumulation of layered drawing, text, and imagery, along with one video projection. As the viewer, I crouched, scanned, read, and reread while hypnotized by Sade’s “Smooth Operator,” for which the exhibition—which champions “bumpiness”—is named. Rasheed and I met via video conference and discussed authority in relation to annotation, opacity as an artist’s tool, and sustaining curiosity.

Courtney McClellan: Annotation and revisions seem to be at the center of this exhibition, and your practice overall. What sparked your interest in annotation?

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I used to be a high school history teacher. A large part of that practice involved supporting students in looking at primary sources, not just to capture or extract some type of scenario or summary, but for them to engage in close reading. Annotation is a protocol we use in instructional practices. This pedagogical approach, when included in an art practice, is pointing people’s attention, not towards passive reading or passive processes of engaging with art or ideas, but this active process, where, not only are you looking at the things but, in terms of revision, you’re going back and looking again, adding [to] your thoughts from your reflections. You revisit a former version of yourself through those annotations. One of the things I often enjoy is going back and looking at things that I annotated years ago to see where my brain was. It is my old self meeting my current self. So, that’s one element of it.

I think that there’s both [a] right and [a] responsibility that I associate with revision. We have the responsibility to constantly be in a state of movement, constantly be in a state of reflection, in revision, and actively not correcting. I don’t think about the language of correcting, but to actively interrogate how we got to where we are in our thinking and engage in this self-citation practice.

In terms of this exhibit, I’m thinking about annotation as this active way of troubling a quick or fast reading process, where something is very smooth, evenly organized, plain, or easy. To make legible thinking about annotation as [a] productive slowing down, where we’re being asked to read the text, the meta subtext, the markings, and all these other elements that are around the images or the artwork itself.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation view, 2022 [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

The last thing that I’ll add—there is also thinking about Umberto Eco, who talks a lot about the notion of inferential walk. He talks about the role of the reader, and the inferential walks we [take] when we read something and try to make associations and connections. Toni Morrison talks about it, as well, as this improvisation between the author and the reader, where they make up their own tune in relation to the text. In both those examples I’m really interested in nonpassive engagement. Annotation is this invitation for me to be an active reader, but also an invitation for viewers to be active readers, as well. I think the thing that I find most lovely about Eco’s inferential walks is [that] he talks about how ghost chapters are created from that process. This notion, that because you are going through this text and creating this other world in your head—through these associations, connections, indexes—what happens is that ghost chapters are created, and I think that’s a very lovely image. [It’s] this chapter that exists ephemerally, without having a concretized form. But it haunts the original. I think about revisions and annotations as a generative haunt of the so-called original, or core, text.

CM: Often annotation, like margin notes, is a record of an effort towards clarity. But in contrast, you seem to take pleasure in the illegible, the opaque. Can you talk about the benefits of opacity, visually and conceptually?

KJR: One thing I always say about our capacities and vulnerabilities is that what’s illegible to one person isn’t necessarily illegible to another. In making my work, I don’t assume a smooth foundation in terms of everyone coming to the work with the same background or even subjectivity. I think that there are moments that are completely legible to some people that are not legible to others. I find pleasure in that because it’s a reminder, at least for me, that I have no responsibility, nor do I have a desire, to make universal works. Folks have the right—even the language of rights is a bit troubling to me—but you can, and you should play with it. But really, you’re catching a thought and [a] process. When I slow down the thought and try to concretize it, this is what [comes] out. I’m not going to make this difficult to make it difficult. It’s still forming for me, and I can’t give you what I don’t have yet. What I have at this moment is a set of annotations and references and notes and drafts of things.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation view, 2022 [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

That’s what I offer in my installations. They’re never final pieces, where I’m, like, “Here’s what I think.” I’m identified as a learner. As a learner, here are my research notes and here’s how I’m sharing them. I think there’s an aesthetic nature to how I display my work as research notes, as learning notes. But I think, at the core, I never want to offer performative obscurity, and I never want to offer performative clarity. I dance somewhere in the middle, and I think that there’s a choreography to how I arrange work in space. There are things that are extremely clear, and there are things that are not. I think that’s the nature of learning. To assume that, once we create [an] installation, we’ve arrived at this point of clarity feels … unnatural and unnecessary.

I remember, during the artist’s talk on September 1 [2022]—I can’t remember who it was, but they asked to what extent my interest in the unfinished is aesthetic. “Is that an aesthetic? Is that a mindset?” And I remember saying that I think, more than anything, it’s a mindset. And I remember [that], when I got home, I started writing notes to myself to say that it can’t be an aesthetic. That’s how we slipped into the commodification of things. Right? So, for me, it’s not an aesthetic. It may have aesthetic elements to it, but at the first level it is a disposition. It’s a choice for me to wake up and do what Ashon Crawley talks about. In Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility [2016], he writes about being in a state of undoneness—“sustaining undoneness.” If we always think about it as an aesthetic gesture, we miss the actual learning that comes as a part of surrendering to things being unfinished, putting ourselves in the disposition where we want to learn.

I guess the last thing I’ll mention here is the text Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins by Amelia Groom. Beverly Buchanan—I love her work and trajectory. In an endnote, Groom references the work of Trinh T. Minh-ha, specifically a voiceover from her film—her first film—Reassemblage (1982). She speaks about the importance of indirectness. She says, “for me, in the context of late capitalism where externalised directness is ultimately made to serve reductive and consumerist ends, it is important to work with indirection and understatement, if meaning is to grow with each viewer, and if the interstices of active re-inscription are to be kept alive.“ She talks about indirectness, not as this sort of superlative and ridiculous, hyperbolic moment of just being illegible for the sake of it, but she talks about it as a necessary disposition to give yourself space to work through things, I think. Or maybe, she is speaking to a particular pacing to allow for slow accretion of meaning rather than quick and convenient conclusions—smooth readings. I like indirectness, I like the erotics of rubbing up against the edge of something, but not touching it. I think that there’s a lot of pleasure in not trying to make everything complete, simply because it’s impossible to make everything complete. It allows for a bit of hedging, which I don’t think you can create if you put a period at the end of every sentence.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation view, 2022 [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation detail, 2022, ink and paper [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

CM: In the gallery space, I thought about the experience of discovery, of learning something new, but I also thought about the aesthetics of learning. I felt like I could smell the photocopier ink, and I could recognize the academic typeface. How are you employing the aesthetics of learning in your work?

KJR: I’m currently teaching this class at Cooper Union called Teaching as Collaborative Social Practice, which was a class that I inherited from someone else. I feel grateful, and while I’ve made some changes, one of the things that feels most important about that class is thinking about the architecture and spatial environment, and how learning should not be restricted to sitting at a desk and having information given to you. In the ways that I collaborate with that architecture, I’m [asking], “Are there ways that people can learn, that are not directed by a sole facilitator, that allow for discovery?”

There are a lot of ways in which I think about the space. Not strictly pedagogical, I think it’s so much more organized around elements of play, which should be at the center of pedagogy. There’s an element of me being, like, “How do I create play around a series of ideas?” To create space where people are not given something. Not because I don’t think people should be given things. I respect the intellect and subjectivity of the folks coming into this space to say that there are opportunities for them, not so much to discover but to find themselves and find other things.

I think in terms of the actual installation, I like to work with variations of different opacities. I like to work with a lot with layers. I like to hide things in corners of walls. There are some other elements in the show, like the projection. I’ve worked with these small, inexpensive adhesive mirrors to create other points of projection for the video to be seen. There are elements of my experimenting with sightlines and experimenting with layering to invite people to not just stand in the center and walk from thing to thing, but to look behind things, to look under things, to crouch. To look at something [along] one sightline, but then move over to another sightline. There is a deep interest in kinesthetic learning and what it might mean to process spatially, and what it might mean for you to read with your entire body versus just with your eyes.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation view, 2022 [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

CM: The exhibition celebrates bumpiness, rejecting the smoothing out of images and language, [and is] also a rebuff of singular meaning. After hearing the talk and seeing the exhibition, I thought about bumpiness in an auditory way. I thought about tempo, cadence, and pacing. In your talk, you started by saying that when you talk about your work, you get excited and may start speaking quickly, but you also address how the exhibition requires a slowing down. What is the role of pacing or cadence in your practice?

KJR: There’s one video in the show. It’s Smooooooooooooooth Operator [2022], and it’s [referencing a Sade] song that I remember my mom playing [when I was] a kid. I never knew what the song was about, but it reminded me a lot of my mom, because she would listen to it when she was vacuuming. I went back and started looking at the lyrics and listening, and I would watch the video over and over again. And I was, like, “Oh my God! I wonder if there’s any resonance in thinking about machine learning and artificial intelligence in relation to the song.” The song is about this man who’s able to move across the world quite smoothly, being terrible. But there’s a smoothness in the way he’s able to interact. He’s able to assimilate to different environments. He’s able to be very, very imperceptible, and perceptible just when needed. I’m thinking about pace and cadence in that video. One of the things that I questioned—how do I pick up the pace of the song itself?—but not only that. How do I also introduce closed captions that have different lyrics? When I think about tempo and pacing, it’s not so much the pacing or the tempo [as it] is set by the author of the work. Right? It’s also about the perception of the tempo and the pacing. I wanted to play with that. [In the video, I have made] the song slightly off key, and it’s slightly off tempo, and the closed captions [do not reflect] what the song is saying.

There is the change of tempo and pacing in the song itself, but there’s also the change in tempo and pacing in terms of receiving, because you’re trying to make sense of what you’re hearing while also making sense of what you’re seeing. I like to play with some of these moments of perception and recognition. When I think about language capacity or even accessibility, it is rooted in what the author, or the originator, thinks they’re doing versus how it’s perceived and felt by the people who are experiencing it. I want them to be able to play on both sides.

I think part of talking fast, for me, has a lot to do—as part of the question you asked earlier, which was around revision and annotation—[with how,] when I start speaking, I’m trying to catch up to a version of my ideas that I think are clearer. When I speak, I’m constantly trying to chase the thing that I can’t chase, that I can’t capture. I almost end up in a bit of a trance … in a meditative state. Every time I finish a talk, I’m still not there, but there’s something so deeply pleasurable about chasing a thing that I cannot capture. I think each of these artist talks [is its] own sort of mini spiritual experience for me. Going back and listening to myself say things that I never said before to make connections—I think there’s beauty and gray area between perception and intended delivery.

CM: You ask your reader, your viewer, your co-learner for patience, and, in some ways, test their capacity to sit in uncertainty by requesting this kind of engagement. Are you preparing them or training them for something? Asked differently, what kind of relationship do you want with your viewer?

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation detail, 2022, printed black and white photos [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation detail, 2022, ink on canvas [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

KJR: What am I preparing for? [laughs]

I don’t know that I am preparing anyone for anything, but I guess maybe a seed that I’m planting is about [how] generative both slowness and fastness [can be].

I think that part of this conversation around smoothness is about going too fast, because there’s no friction that slows you down. I’m asking a lot of questions around pacing, and I am saying that the work in the show does require durational engagement. And if you’re going to spend a lot of time here, you might want to pick up the pace in other places. This is a place where you can go slow.

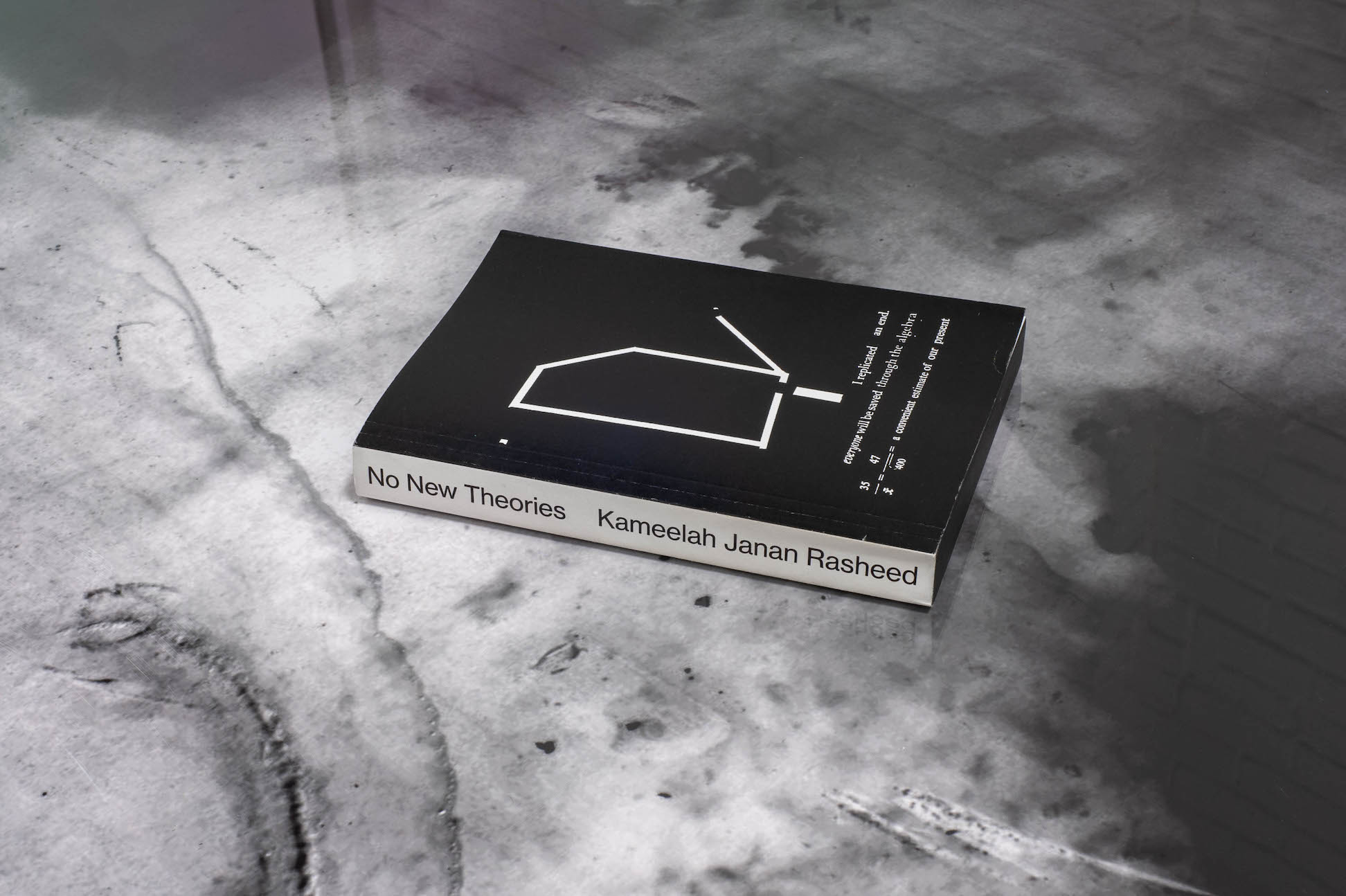

There was a conversation that happened around my book No New Theories [Printed Matter, 2019] in early 2020, when someone asked a question, “Yes, slowness, but what about people who are in the process of suffering? We want to go slow around that?” And I said, “No, we don’t [do that] in very practical matters. Those aren’t the things we want to go slow around.” I’m … not wanting to be in a position where I’m dictating the pace of political change. I do think it’s too slow.

Here’s where I want to say: I don’t want the words to be instrumentalized as a political statement around X, Y, and Z, because I think instrumentalizing artwork ends up being deeply problematic and puts the artist in a position where they become a spokesperson for a series of ideas. But I am interested in troubling the idea of using slowness or gradualism as an attempt to stop social change. There are ways that people intentionally misuse [and] manipulate the notion of slowness to remove culpability.

In Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 Letter From the Birmingham Jail—and I wish more people quoted this letter and not everything else—in that letter he talks about this notion of who sets the timetable for freedom. He talks about the most menacing thing not being the Ku Klux Klan, “but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice … who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom … who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a ‘more convenient season.’“ And this makes me think so much about that concerning … James Baldwin’s The Price of the Ticket, where he asks, ”How much time do you want for your progress?” And then, of course, Nina Simone, who talks about this in “Mississippi Goddam.” She sings, ”They keep on saying ‘Go slow!’ But that’s just the trouble.”

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Smooooooooooooooth Operator, installation detail, 2022, printed matter [photo: Kevin Patrick Bond; courtesy of the artist and the Athenaeum, Athens, GA]

CM: I read an interview in Nylon magazine, in which you quoted Zora Neale Hurston saying, “Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose.” Does your curiosity ever run out? How do you, the learner, stoke or sustain curiosity?

KJR: I wish it didn’t run out. I would argue that one of the things I’ve struggled with the most is that I have so many ideas and so many things to work on. Every day, I start building more connective tissue to more ideas, and I find that really overwhelming. Part of my deep interest in the unfinished is that I don’t know how to function any other way.

I don’t think that it has to run out. I don’t think that it will. I’m very grateful to my parents, who never told me anything was out of bounds. I feel like there’s a lot of space to expand and continue to research and be curious.

Courtney McClellan is an artist and writer originally from Greensboro, NC. Her work addresses speech, performance, and civic engagement. She has served as the Fountainhead Fellow in the Sculpture and Extended Media Department at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA; the Roman J. Witt Artist in Residence at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI; and an Innovator in Residence at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.