Jonathan Lasker: Visible Thoughts

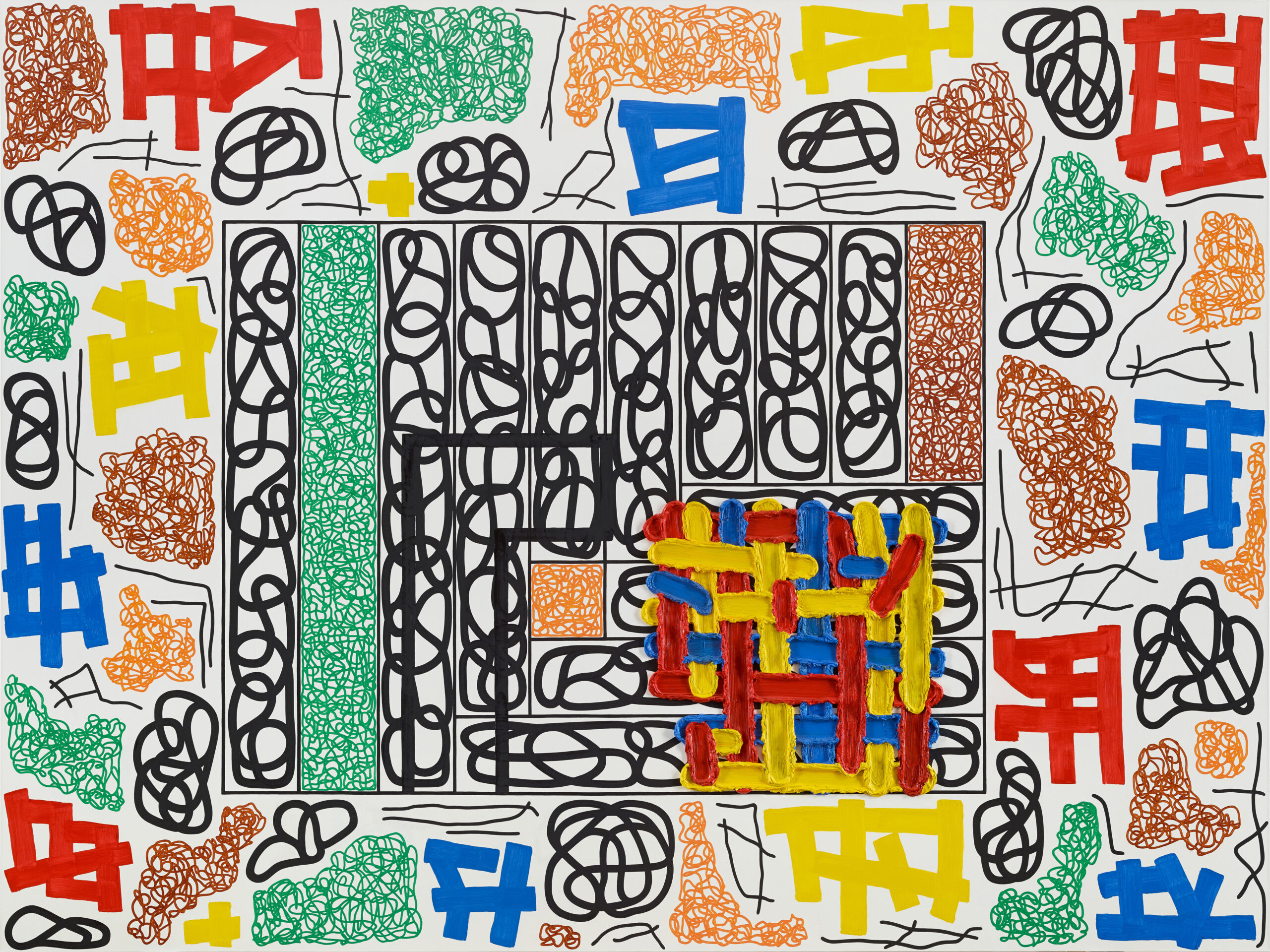

Jonathan Lasker, Main Event, 1981, oil and alkyd on canvas, 48 x 72 inches [courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York]

Share:

This feature was originally published in ART PAPERS September/October 2001, Vol. 25, issue 5.

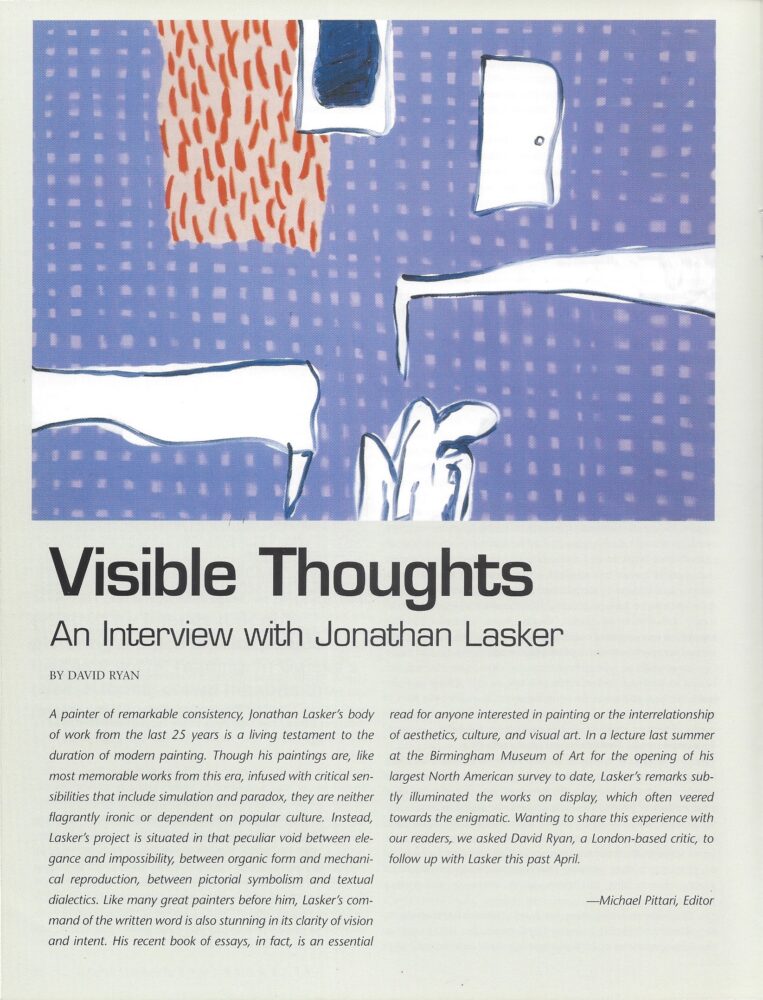

A painter of remarkable consistency, Jonathan Lasker’s body of work from the last 25 years is a living testament to the duration of modern painting. Though his paintings are, like most memorable works from this era, infused with critical sensibilities that include simulation and paradox, they are neither flagrantly ironic or dependent on popular culture. Instead, Lasker’s project is situated in that peculiar void between elegance and impossibility, between organic form and mechanical reproduction, between pictorial symbolism and textual dialectics. Like many great painters before him, Lasker’s command of the written word is also stunning in its clarity of vision and intent. His recent book of essays, in fact, is an essential read for anyone interested in painting or the interrelationship of aesthetics, culture, and visual art. In a lecture last summer at the Birmingham Museum of Art for the opening of his largest North American survey to date, Lasker’s remarks subtly illuminated the works on display, which often veered towards the enigmatic. Wanting to share this experience with our readers, we asked David Ryan, a London-based critic, to follow up with Lasker this past April.

–Michael Pittari, Editor

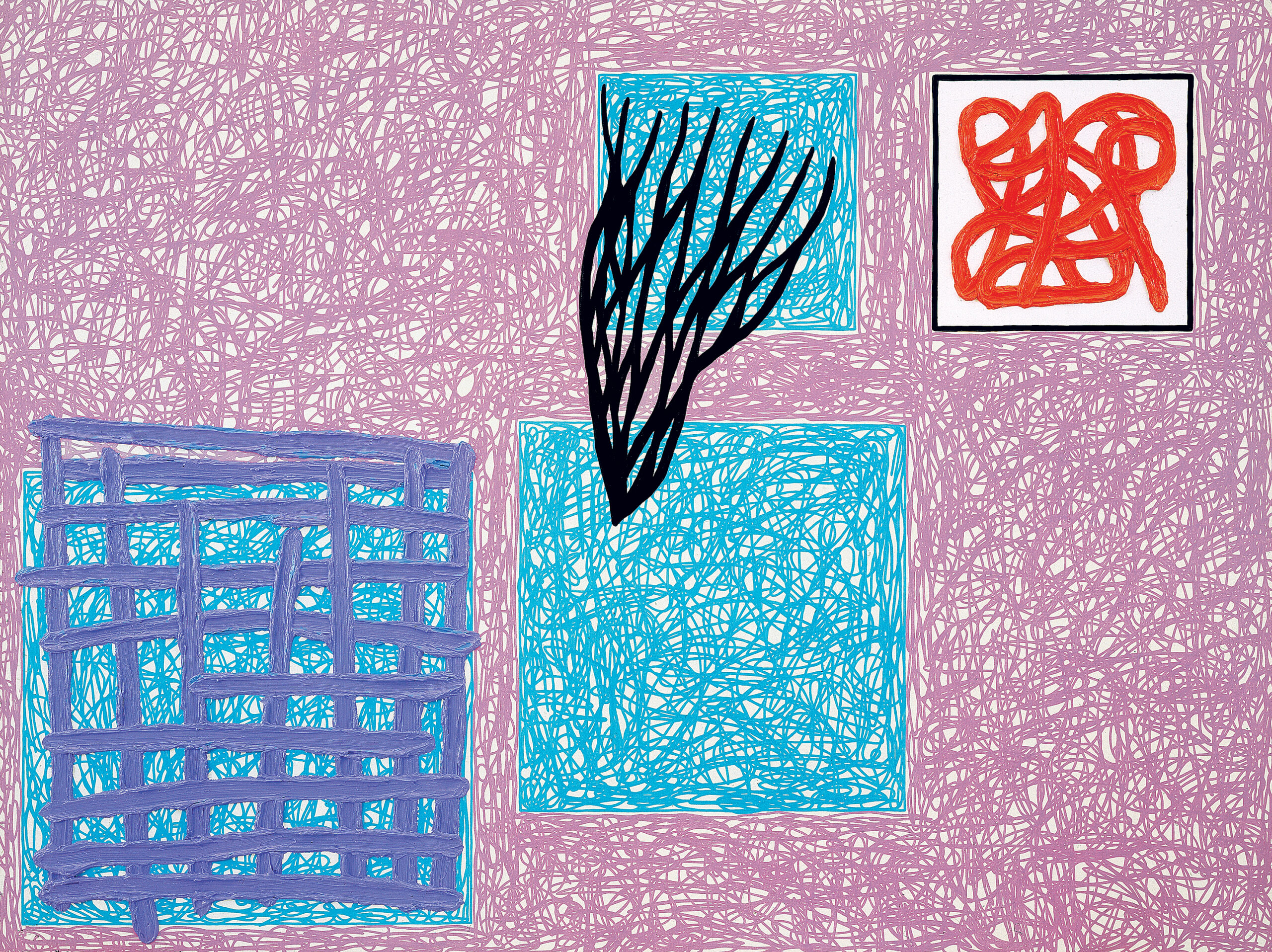

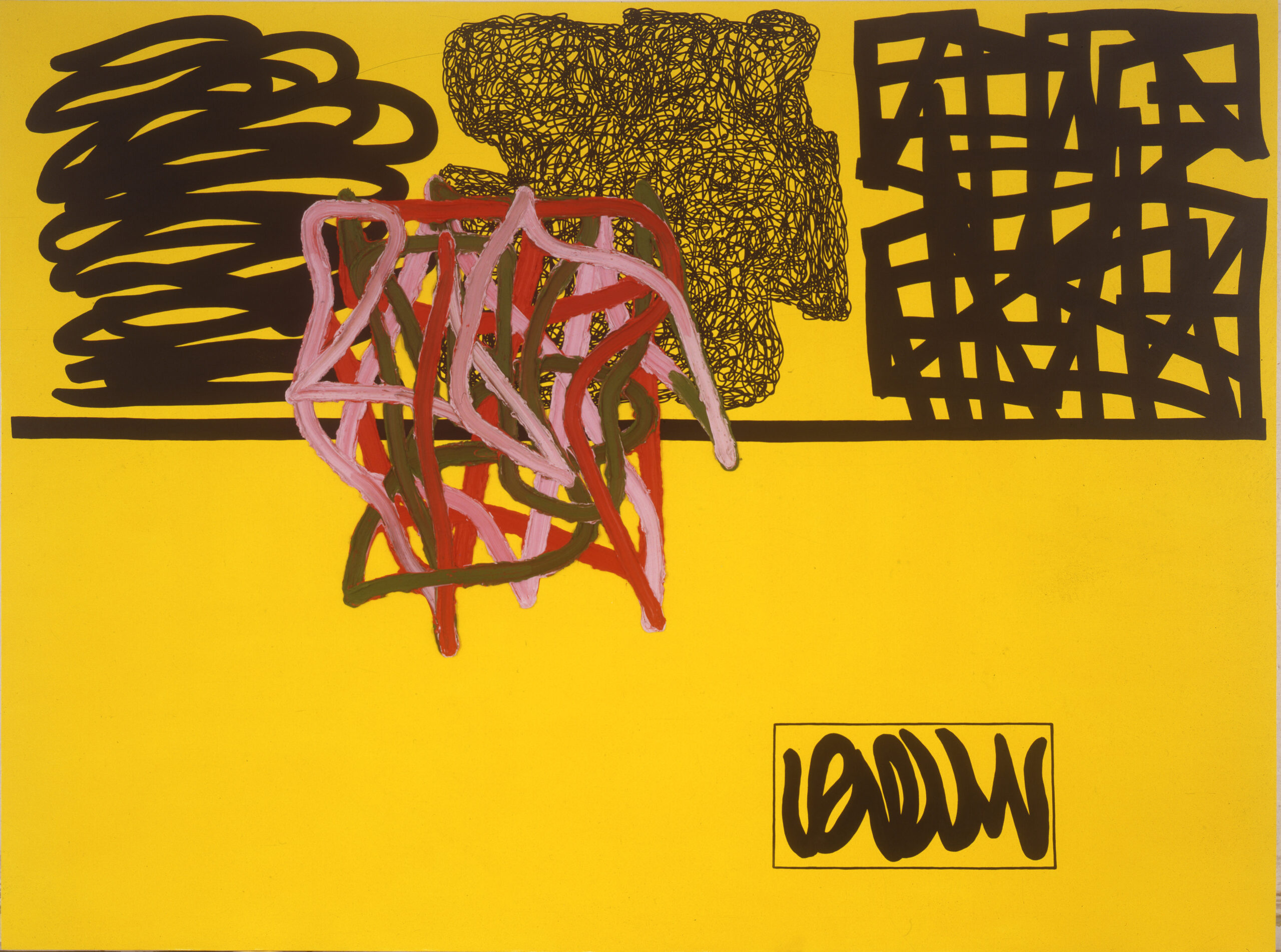

Jonathan Lasker, Born Yesterday: Drawing into Painting, 1987-2020, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York]

David Ryan: I would like to begin with asking about your formative years in the late ‘70s. How do you now perceive this period thinking back to the time, in particular for a young painter attempting to find his own voice?

Jonathan Lasker: In the late ‘70s painting had reached an endgame, a kind of closure, which to my mind was based on trying to paint the last possible picture. We had inherited the ideas of Ad Reinhardt, who had, of course, attempted to paint the “last painting” for himself. To this we might also add Frank Stella’s project with his early black paintings, and of course Minimalism. The notion of completing the project of painting was aligned to emptying out the picture plane and reducing it to its basic elements, as per Clement Greenberg’s prescription of two-dimensional space—or rather a “literalised” version of this outlook—which outlawed metaphor and picture making.

DR: Still at this time?

JL: Yes, and this was the “challenge” as I perceived it. Some other painters were questioning that inheritance—the New Image Painters, and prior to that, the Pattern Painters who were doing things with two-dimensional patterns, but allowing more scope for metaphor, or even a hint of narrative. That project quickly died, and is now half remembered and somewhat buried in history. It was a minor movement, but an interesting position for young painters to look at, and so I started painting all-over pattern paintings, which were rather painterly and had some connection with natural landscape in terms of their coloration.

DR: So these were the roots of your present concerns?

JL: In a way, yes. The surfaces of those early paintings were made of large stroke-like forms cutting into one another, which as I said formed all-over patterns. But, after a while I was dissatisfied with these on their own, so I started to invade the patterns by painting very brushy off-white biomorphic forms on top of these fields. I would then paint a black line off register into those shapes. This implied a plane with outline and accentuated the resonance of those forms on the patterned grounds. This constructed duality became the beginnings of my painting development, and set up the formal game that was involved. Figure, ground, line, and their spatial implications were clear to me. Other implications slowly emerged over the years. But it was a way of re-engaging metaphor, and to re-assert figure/ground relationships, which is, in fact, the rudiments of representational painting. It’s sort of like taking human history back to Adam.

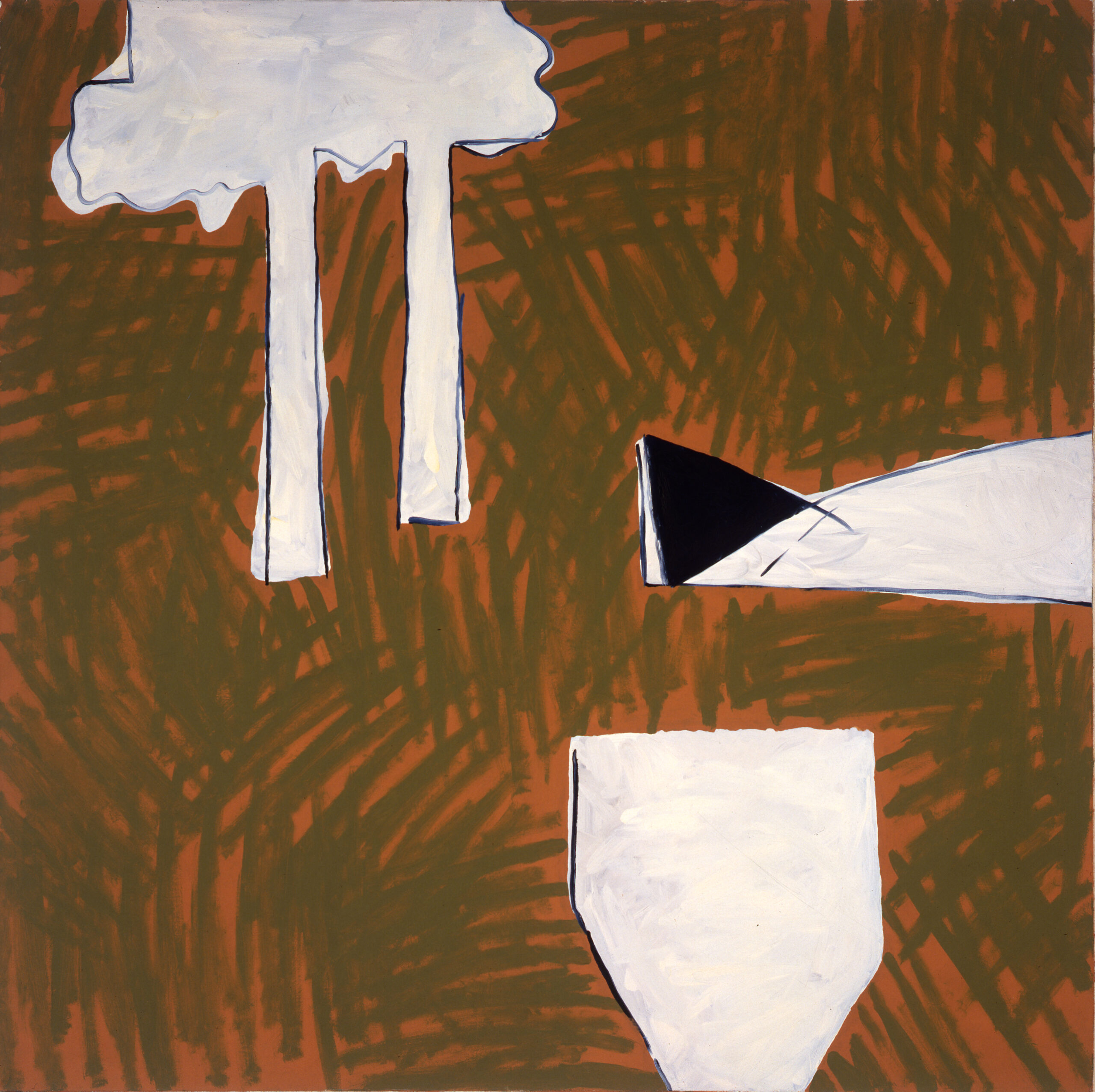

Jonathan Lasker, The View From Home Plate, 1978. oil on canvas, 67 x 67 inches [image courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York]

DR: You mean in order to sidestep those historical constraints or that sense of the seeming inevitable “completion” of painting?

JL: Well, within the context you have raised—about history, or particular inherited histories of painting in this case—one doesn’t have to accept the given history, one can go back to the beginning and there can be another route from that historical juncture. In the ‘70s the literalist, endgame approach to painting was still the dominant inherited history. One either bought into it or found a way of providing an alternative. There was the danger of painting oneself into a corner, and also socially—in terms of social development—pushing ourselves into a corner by saying that there is only one way forward. We are, of course, at a point where people are re-considering history, and re-considering the present. On a modest scale, within painting, I was thinking about some of these problems.

DR: The ‘70s have also been discussed in terms of pluralism—I guess the sense of loss at that time in relation to the great dominant “movements” of the avant-garde, which was also responsible for such reconsiderations of historical progression?

JL: I’m not too sure if that had gained such currency at that time; I think the ideas of pluralism or eclecticism were more of an early ‘80s thing. I think that what was happening—at least in American painting—was a handful of painters who were trying to find their way painting against certain taboos which had been set up. The New Image painters were involved with that. Unfortunately only a couple of them were really good artists, but those who were, produced some very interesting things: early Susan Rothenberg—the horse paintings, the heads, hands etc.; and Robert Moskowitz has remained consistently a very interesting and vital painter. There were also some abstract painters who were attempting to open up form by playing with figure/ground in an interesting way.

DR: Which other painters apart from the Pattern or New Image Painters did you feel provided the most pertinent lessons for you as a painter?

JL: From another perspective, I would say that Johns and Rauschenberg were important to me, particularly in regard to how they treated gesture. Treating it, that is, in an analytical manner. Johns’ method of codifying touch on a certain level—this was very interesting to me. So their thinking was informative, and I still sense something of the spirit of their thinking in the present paintings.

Jonathan Lasker, Main Event, 1981, oil and alkyd on canvas, 48 x 72 inches [courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York]

JL: In my mind I’m still making the paintings from 1977-80. I guess people looking at it from the outside see the early pictures as precursors of my current work. If one thinks in terms of consistent preoccupations, then the three elements I mentioned earlier—figure, grounf, line—have remained my basic formal vocabulary. How I load these individual elements with possibilities, or play one off against the other, makes the specific picture what it is. In the early paintings I sometimes had figurative or landscape references which were clearly defined. So those paintings were not always fully abstract; they went back and forth for about three years, until about 1980 when I distinctly broke with representational form in its conventional sense. In the beginning though, I had the idea of forming visual space and breaking it down at the same time. That was an important concern. Today, the paintings are still involved in picture making, in a way because my abstract forms act like surrogate figures.

DR: David Moos has also mentioned Guston, Twombly, even Ryman…

JL: I think they are great painters, important artists, but none of them were directly informative to me. Perhaps something of Guston’s way of putting line into paint, you know, these off register lines that I mentioned a moment ago, did owe something to his example. But these passages were then placed by me on an alien background, something he would never do.

DR: What about the legacy of conceptualism, did that hold any interest?

JL: Not really, although I think a lot of the conceptualism of the late 60’s, early ‘70s was extremely interesting. But that was not something that informed my thinking as a painter. I think that painting is, unto itself, a conceptual pursuit; it has its own particular history of conception and I was engaged with that.

DR: This is probably a long shot, but what about somebody like Sol LeWitt, I’m thinking of his systematic and yet wobbly line drawings, and the process basis of his wall-based works. Was there a tangential reference here?

JL: I am interested in process, but I’d say Ryman interests me more than LeWitt. At that time I think I hated Sol LeWitt’s work; I have now come to admire it. At that point, being reductively locked into a system was something I wanted to avoid.

DR: Looking at a piece from this period such as Moody Room of 1977, we can clearly identify some of the formal qualities and concerns which might be distantly related to the present ones—the problems, for instance, of the habituation of space (as in figure and interior) and its translation onto the two dimensional physical plane of the canvas. Do you still see this figure/environment relationship as important to the work—albiet on a metaphorical level? The idea, for example, of forms seemingly physically inhabiting space?

JL: In my mind I’m still making the paintings from 1977-80. I guess people looking at it from the outside see the early pictures as precursors of my current work. If one thinks in terms of consistent preoccupations, then the three elements I mentioned earlier—figure, grounf, line—have remained my basic formal vocabulary. How I load these individual elements with possibilities, or play one off against the other, makes the specific picture what it is. In the early paintings I sometimes had figurative or landscape references which were clearly defined. So those paintings were not always fully abstract; they went back and forth for about three years, until about 1980 when I distinctly broke with representational form in its conventional sense. In the beginning though, I had the idea of forming visual space and breaking it down at the same time. That was an important concern. Today, the paintings are still involved in picture making, in a way because my abstract forms act like surrogate figures.

DR: And one could real the grounds as either interior or exterior space?

JL: I think that’s right. There are patterns in the paintings’ grounds that can be seen as representing those spaces.

DR: It is relevant here that you have referred to the works as “abstract pictures” rather than abstract paintings per se. I presume it is because of the metaphorical overtones of a basic “ontology” of form—how forms react and interact with their given environment—for example, how a figure might inhabit a space and the reciprocal energies set up by this environmental placement?

JL: It has to do with perception, with how we form images in our mind in order to get to identify things to get through the day and form reference points. At any given time we are all looking at a congeries of things and how we identify is critical to our being in the world. These paintings are a little bit about deconstructing that capacity to identify forms—it’s a step back from taking that process for granted and asking, what actually is this process of recognition?

DR: What is striking about the forms in the paintings is how they have very particular countenances…

JL: I think this can be read in two ways: sometimes it has a very physical countenance, due to the palpable dimension of the paint which almost literally steps into the third dimension, into the space of the viewer; and then they might have a presence which has to do with spatial presence, with pictorial presence. We are led back to that issue of how you actually identify a form, and also this problem of universals and particulars: At what point does a form become recognizable as a universal form? And what characterizes a cluster of marks as being read collectively as a form? What makes them cohere in our perception in this way? The idea is to address these questions and also to unfurl the sensations of being in a space.

DR: And yet you are always holding back from direct recognition…

Jonathan Lasker, Love’s Rhetoric, 1990. Oil on Linen, 60 x 80 inches (152 x 203 cm) Image courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

DR: This comes across if we look at a painting like Sensible Arrangement from 1995—comparing it to the earlier pieces…

JL: Well, yes, I think that is a good example. In that painting two forms attempt to compel a sense of reality, and we might see the more “physical” one as more real, the other form as less real; of course what we are looking at are two fictions. The tri-colored form steps forward in space while the other linear form suggests an image rather than a reality. But on a pictorial level, the linear form is as much a figure as the tri-colored form. These forms inhabit the space of still-life painting but they are not specific objects depicted.

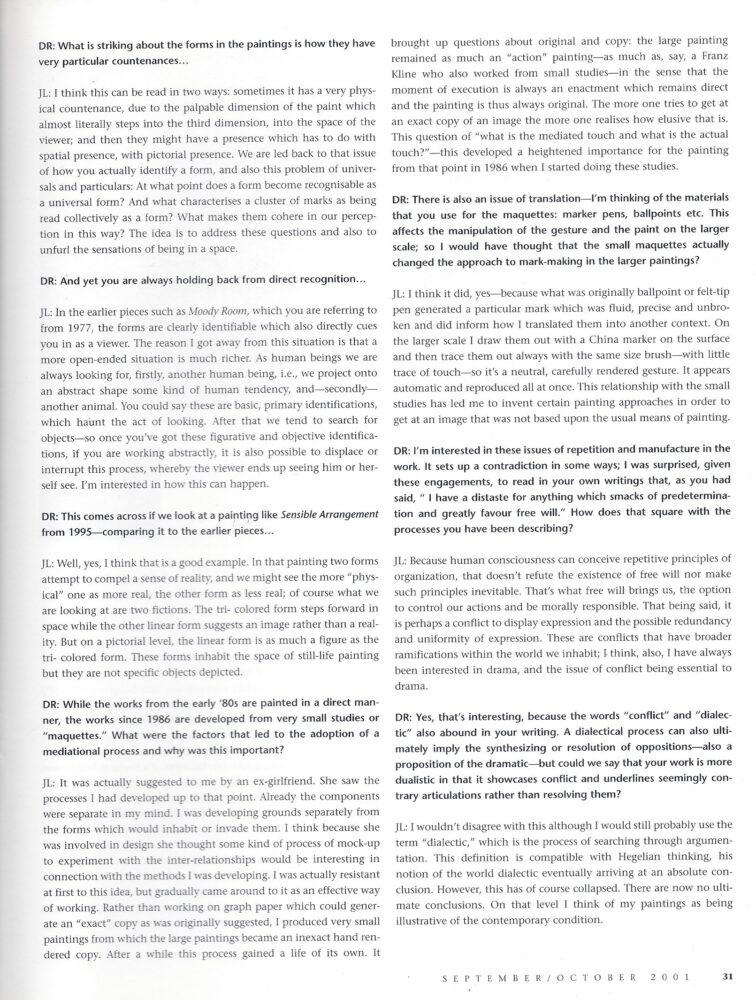

DR: While the works from the early ‘80s are painted in a direct manner, the works since 1986 are developed from very small studies or “maquettes.” What were the factors that led to the adoption of mediational process and why was this important?

JL: It was actually suggested to me by an ex-girlfriend. She saw the processes I had developed up to that point. Already the components were separate from in my mind. I was developing grounds separately from the forms which would inhabit or invade them. I think because she was involved in design she thought some kind of process of mock-up to experiment with the inter-relationships would be interesting in connection with the methods I was developing. I was actually resistant at first to this idea, but gradually came around to it as an effective way of working. Rather than working on graph paper which could generate an “exact” copy as was originally suggested, I produced very small paintings from which the large paintings became an inexact hand rendered copy. After a while this process gained a life of its own. It brought up questions about original and copy: the large painting remained as much an “action” painting—as much as, say, a Franz Kline who also worked from small studies—in the sense that the moment of execution is always an enactment which remains direct and the painting is thus always original. The more one tries to get at an exact copy of an image the more one realizes how elusive that is. This question of “what is the mediated touch and what is the actual touch?”—this developed a heightened importance for the painting from that point in 1986 when I started doing these studies.

DR: There is also an issue of translation—I’m thinking of the materials that you use for the maquettes: marker pens, ballpoints etc. This affects the manipulation of the gesture and the paint on the larger scale; so I would have thought that the small maquettes actually changed the approach to mark-making in the larger paintings?

JL: I think it did, yes—because what was originally ballpoint or felt-tip pen generated a particular mark which was fluid, precise and unbroken and id inform how I translated them into another context. On the larger scale I draw them out with a China marker on the surface and then trace them out always with the same brush—with little trace of touch—so it’s a neutral, carefully rendered gesture. It appears automatic and reproduced all at once. This relationship with the small studies has led me to invent certain painting approaches in order to get at an image that was not based upon the usual means of painting.

DR: I’m interested in these issues of repetition and manufacture in the work. It sets up a contradiction in some ways; I was surprised, given these engagements, to read in your own writings that, as you had said, “I have a distaste for anything which smacks of predetermination and greatly favour free will.” How does that square with the processes you have been describing?

JL: Because human consciousness can conceive repetitive principles of organization, that doesn’t refute the existence of free will nor make such principles inevitable. That’s what free will brings us, the option to control our actions and be morally responsible. That being said, it is perhaps a conflict to display expression and the possible redundancy and uniformity of expression. These are conflicts that have broader ramifications within the world we inhabit; I think, also, I have always been interested in drama, and the issue of conflict being essential to drama.

DR: Yes, that’s interesting, because the words “conflict” and “dialectic” also abound in your writing. A dialectical process can also ultimately imply the synthesizing or resolution of oppositions—also a proposition of the dramatic—but could we say that your work is more dualistic in that it showcases conflict and underlines seemingly contrary articulations rather than resolving them?

JL: I wouldn’t disagree with this although I would still probably use the term “dialectic,” which is the process of searching through argumentation. This definition is compatible with Hegelian thinking, his notion of the world dialectic eventually arriving at an absolute conclusion. However, this of course collapsed. There are now no ultimate conclusions. On that level I think of my paintings as being illustrative of the contemporary condition.

DR: Is the viewer potentially a site of synthesis or resolution—in that, ultimately, it’s up to them to synthesize those conflicts that you set up within a painting?

JL: The viewer always completes the picture. I am very interested in my viewers and setting them to work.

DR: I also get the feeling that you want each painting to be experienced on a direct one-to-one level with the viewer? It’s the singularity of each piece that you want to speak to—or address—the viewer?

JL: Absolutely. I have always emphasized the different types of pictures in each exhibition. I do not elaborate a theme or show a series of paintings, and I want the viewer to be engaged with each picture, and think about each one, and determine each picture for him or herself.

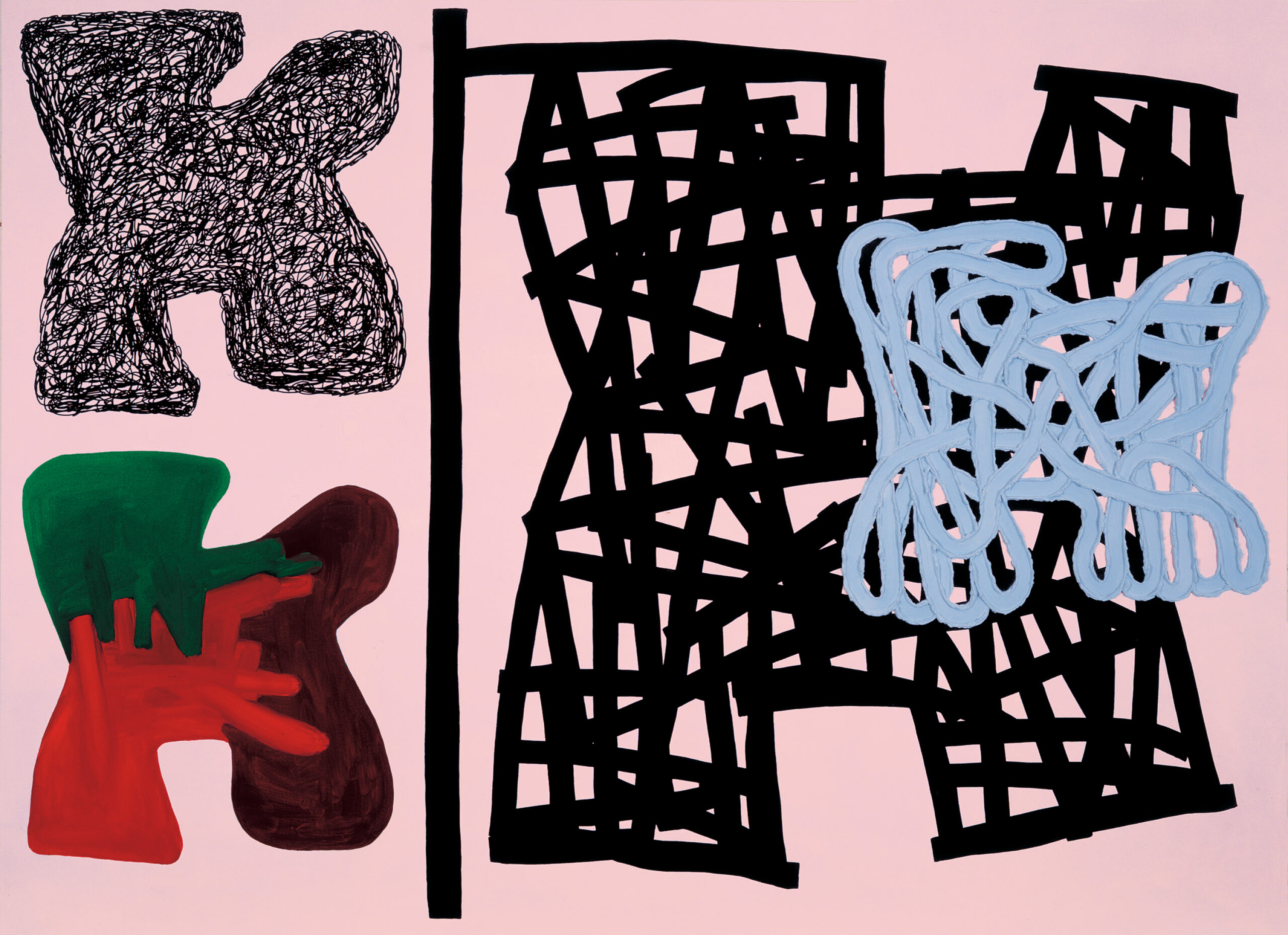

Jonathan Lasker, The Eternal Silence of Infinite Space, 1994. Oil on Canvas, 90 x 120 inches (229 x 305 Image courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York cm)

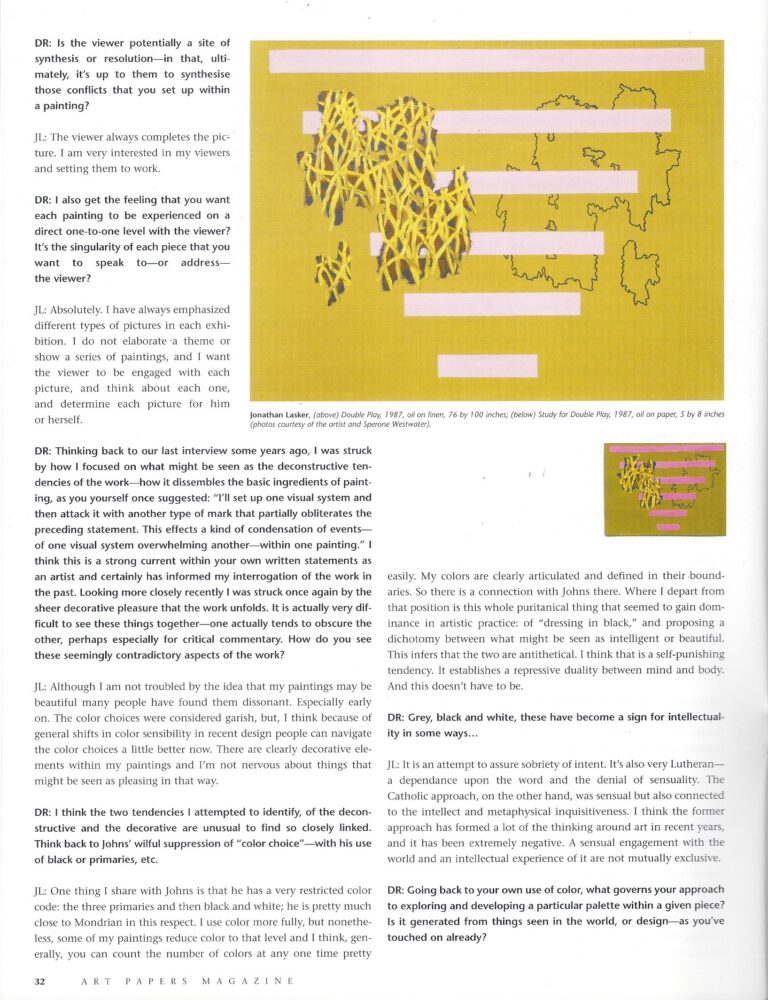

JL: Although I am not troubled by the idea that my paintings may be beautiful many people have found them dissonant. Especially early on. The color choices were considered garish, but, I think because of the general shifts in my color sensibility in recent design people can navigate the color choices a little better now. There are clearly decorative elements within my paintings and I’m not nervous about things that might be seen as pleasing in that way.

DR: I think the two tendencies I attempted to identify, of the deconstructive and the decorative are unusual to find so closely linked. Think back to Johns’ wilful suppression of “color choice”—with his use of black or primaries, etc.

JL: One thing I share with Johns is that he has a very restricted color code: the three primaries and then black and white; he is pretty much close to Mondrian in this respect. I use color more fully, but nonetheless, some of my paintings reduce color to that level and I think, generally, you can count the number of colors at any one time pretty easily. My colors are clearly articulated and defined in their boundaries. So there is a connection with Johns there. Where I depart from that position is this whole puritanical thing that seemed to gain dominance in artistic practice: of “dressing in black,” and proposing a dichotomy between what might be seen as intelligent or beautiful. This infers that the two are antithetical. I think that is a self-punishing tendency. It establishes a repressive duality between mind and body. And this doesn’t have to be.

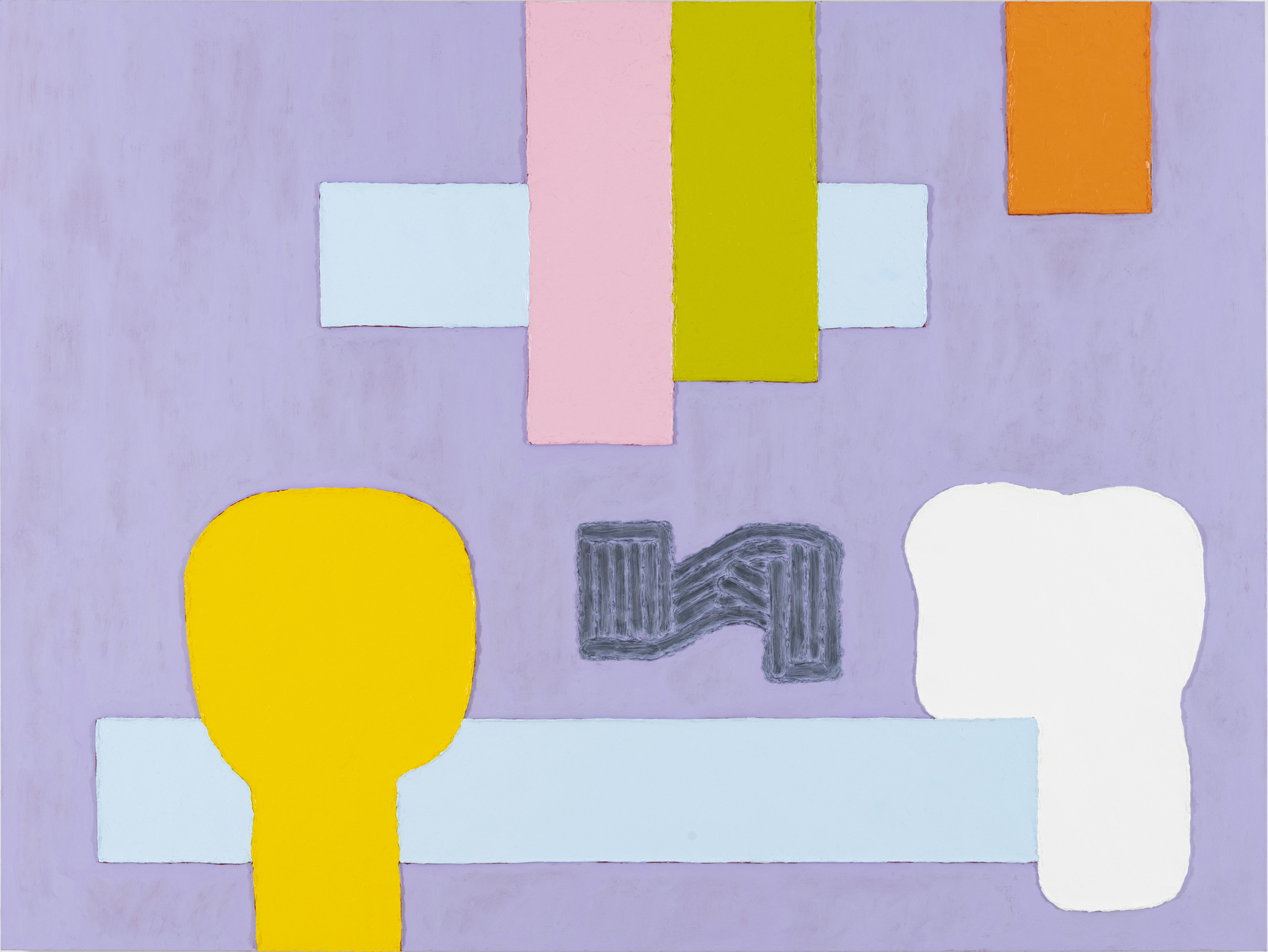

Jonathan Lasker, The Universal Frame of Reference, 2014. Oil on Linen, 90 x 120 inches (229 x 305 cm) Image courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

DR: Grey, black and white, these have become a sign for intellectuality in some ways…

JL: It is an attempt to assure sobriety of intent. It’s also very Lutheran—a dependance upon the word and the denial of sensuality. The Catholic approach, on the other hand, was sensual but also connected to the intellect and metaphysical inquisitiveness. I think the former approach has formed a lot of the thinking around art in recent years, and it has been extremely negative. A sensual engagement with the world and an intellectual experience of it are not mutually exclusive.

DR: Going back to your own use of color, what governs your approach to exploring and developing a particular palette within a given piece? Is it generated from things seen in the world, or design—as you’ve touched on already?

JL: It’s interesting that you mention design again, because in design each object is usually given a local color and in my paintings each element has a local color. They are clear articulated colors suggesting discrete boundaries of forms. This has a codifying effect and leads you to perceive each element. I seek to break down the world into isolated forms. Color helps me achieve this.

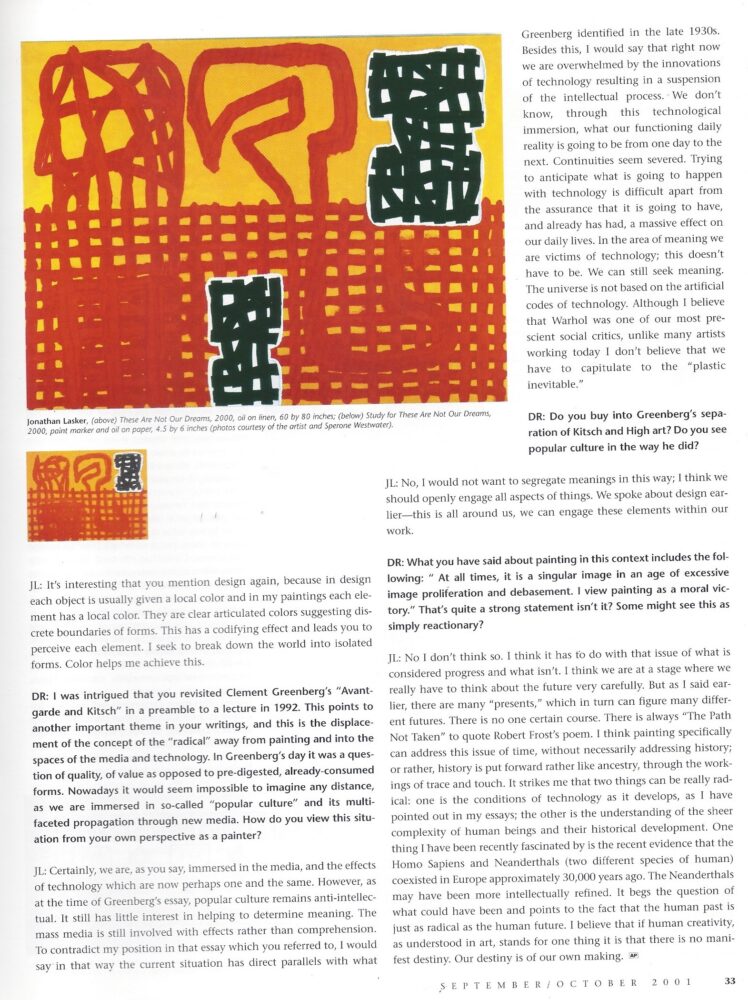

DR: I was intrigued that you revisited Clement Greenberg’s “Avant-garde and Kitsch” in a preamble to a lecture in 1992. This points to another important theme in your writings, and this is the displacement of the concept of the “radical” away from painting and into the spaces of the media and technology. In Greenberg’s day it was a question of quality, of value as opposed to pre-digested, already-consumed forms. Nowadays it would seem impossible to imagine any distance, as we are immersed in a so-called “popular culture” and its multifaceted propagation through new media. How do you view this situation from your own perspective as a painter?

JL: Certainly, we are, as you say, immersed in the media, and the effects of technology which are now perhaps one and the same. However, as at the time of Greenberg’s essay, popular culture remains anti-intellectual. It still has little interest in helping to determine meaning. The mass media is still involved with effects rather than comprehension. To contradict my position in that essay which you referred to, I would say in that way the current situation has direct parallels with what Greenberg identified in the late 1930s. Besides this, I would say that right now we are overwhelmed by the innovations of technology resulting in a suspension of the intellectual process. We don’t know, through this technological immersion, what our functioning daily reality is going to be from one day to the next. Continuities seem severed. Trying to anticipate what is going to happen with technology is difficult apart from the assurance that it is going to have, and already has had, a massive effect on our daily lives. In the area of meaning we are victims of technology; this doesn’t have to be. We can still seek meaning. The universe is not based on the artificial codes of technology. Although I believe that Warhol was one of our most prescient social critics, unlike many artists working today I don’t believe that we have to capitulate to the “plastic inevitable.”

DR: Do you buy into Greenberg’s separation of Kitsch and High Art? Do you see popular culture in the way he did?

JL: No, I would not want to segregate meanings in this way; I think we should openly engage all aspects of things. We spoke about design earlier—this is all around us, we can engage these elements within our work.

DR: What you have said about painting in this context includes the following: “At all times, it is a singular image in an age of excessive image proliferation and debasement. I view painting as a moral victory.” That’s quite a strong statement isn’t it? Some might see this as simply reactionary?

JL: No, I don’t think so. I think it has to do with that issue of what is considered progress and what isn’t. I think we are at a stage where we really have to think about the future very carefully. But as I said earlier, there are many “presents,” which in turn can figure many different futures. There is no one certain course. There is always “The Path Not Taken” to quote Robert Frost’s poem. I think painting specifically can address this issue of time, without necessarily addressing history; or rather, history is put forward rather like ancestry, through the workings of trace and touch. It strikes me that two things can be really radical: one is the conditions of technology as it develops, and I have pointed out in my essays; the other is the understanding of the sheer complexity of human beings and their historical development. One thing I have been recently fascinated by is the recent evidence that the Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals (two different species of human) coexisted in Europe approximately 30,000 years ago. The Neanderthals may have been more intellectually refined. It begs the question of what could have been and points to the fact that the human past is just as radical as the human future. I believe that if human creativity, as understood in art, stands for one thing is that there is no manifest destiny. Our destiny is of our own making.

Jonathan Lasker, Superior Domesticity, 2022. Oil on Linen, 60 x 80 inches (152 x 203 cm) Image courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

David Ryan is a painter and writer based in London. In addition to lecturing on abstract painting at institutions including the National University of Mexico, Forum Konkrete Kunst, Warwick Arts Centre, and the Tate Liverpool, he has written extensively on art and music for publications such as Modern Painters, Munich, Dissonanz, Leonardo Music Journal, Contemporary Visual Arts and Tempo. He has also written various catalogue essays as well as numerous reviews for Artpress.