Nicole Eisenman: Fantastic Worlds

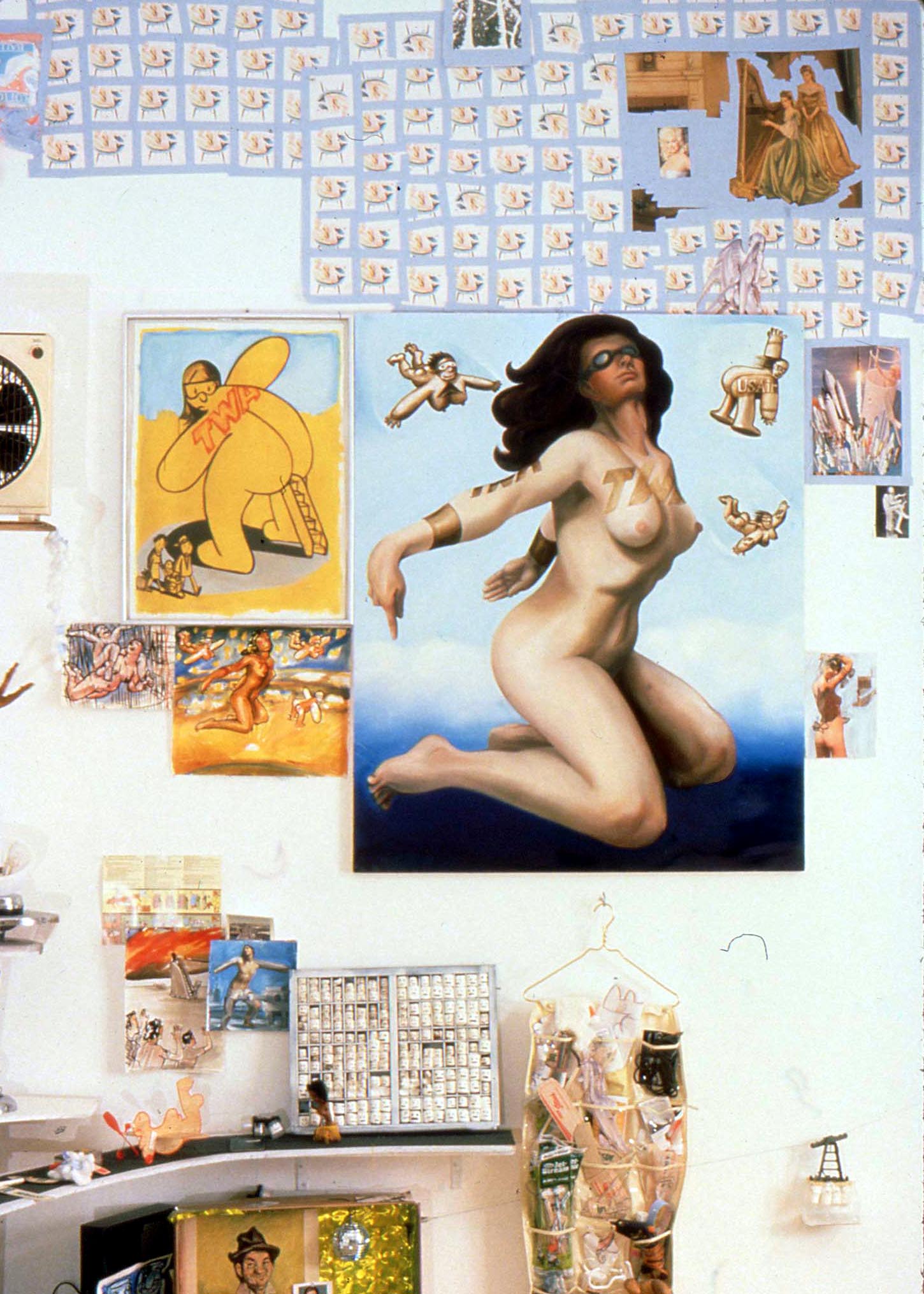

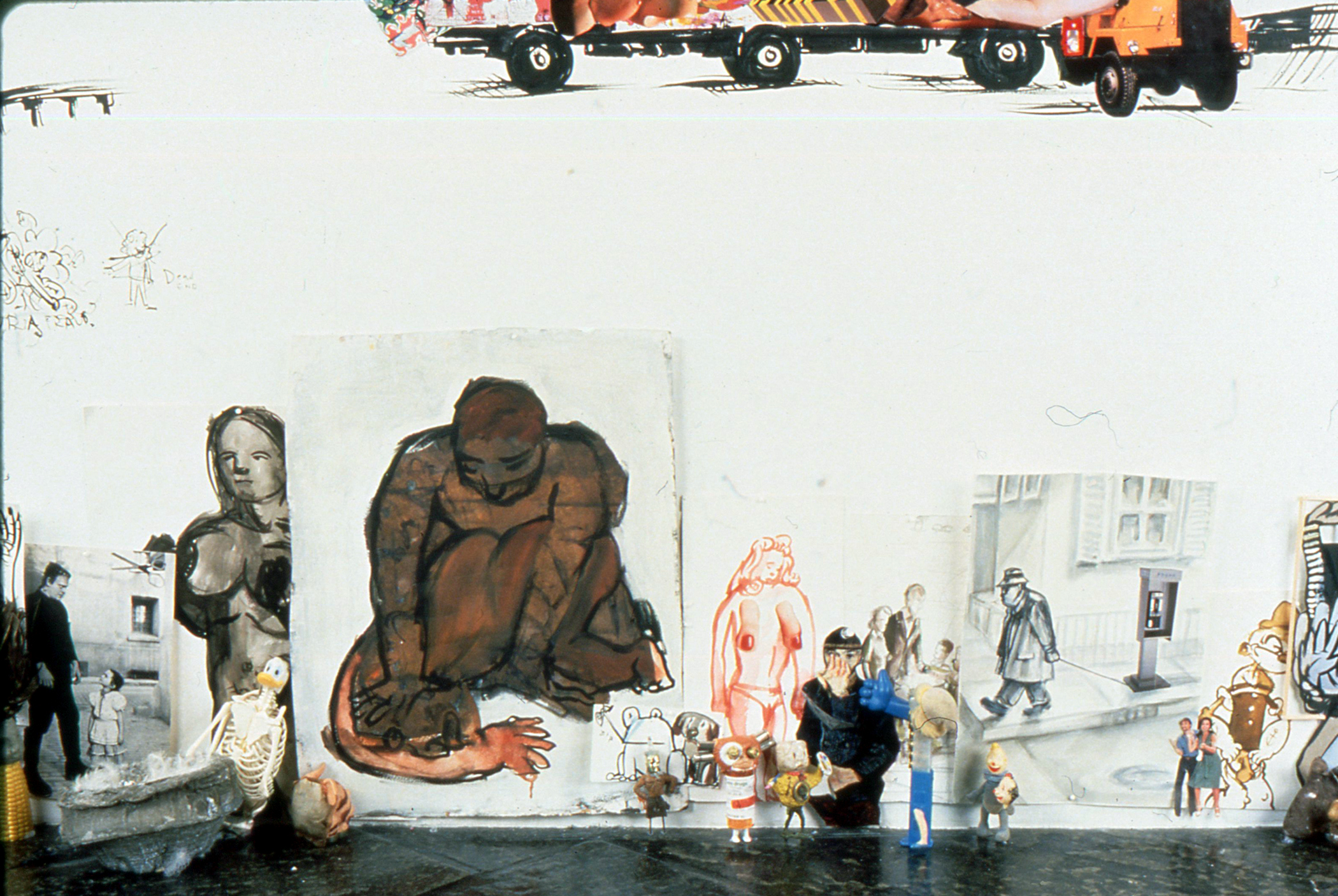

Nicole Eisenman, Airport, installation view at Grenoble, France, 1997 [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS July/August 2000, Vol. 24, issue 4.

Nicole Eisenman lives and works in a loft in the heart of Chinatown. Walking down her street, I was jostled by people briskly moving through the restaurants and shops that line the pavement. Nearby jackhammers sang their monotonous song in the street. When the door buzzer signaled my entrance, the difference could not have been more stark. Climbing up to her third floor space, my only view was of four men silently playing Mah Jongg in a sparsely decorated room, a common pastime according to my host.

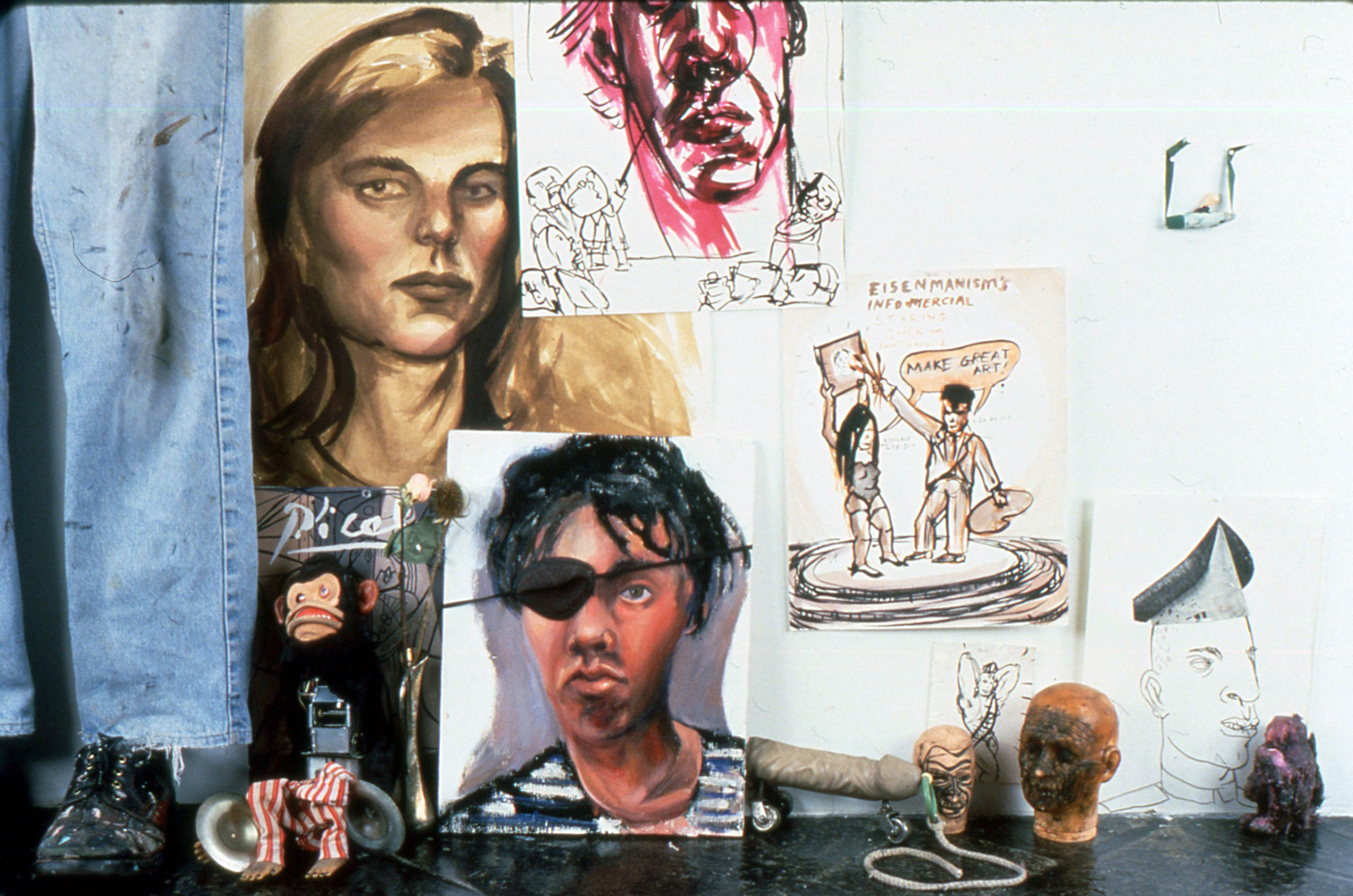

Eisenman’s loft is quite similar to these surroundings. In places she has pasted dense arrangements of “stuff” on the walls-torn magazine clippings, photos, even her own drawings. In contrast to these busy areas, the tonal simplicity of the decor gives the illusion of quiet space. It was the perfect setting for the following conversation, in which we touched on topics that range from the activity that feeds her installations to the more confident, thoughtful approach she now brings to her work

– Rebecca Dimling Cochran

Original lay out of this interview in the July / August issue ART PAPERS in 2000.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran: You often exhibit your work in large rambling assemblages of paintings, drawings, and found objects that engage in a dialogue with a wall and the floor space in front of it. Do you think about the space first or do you think about the evolution of the piece?

Nicole Eisenman: Initially, I think more about the theme of the piece. I’m not as concerned with the space I’m showing in as I am with the material going into the installation. Of course, the architecture, the shape of the walls and the atmosphere will influence the piece, but I usually can be really flexible with the shape of the space.

RDC: This allows you a great amount of freedom to translate work to different spaces. Do you do that often?

NE: There was an installation called “Airport” that I did in a little corner space at the Jack Tilton Gallery in 1996, and the next year I took the installation to Le Magazin in Grenoble, France, and put it on a 20-foot curved wall. Half of the process happens in my studio when I make a lot of the elements that go into the installation. But the piece comes to life as I’m working on the walls and doing the installation in the space. It’s a spontaneous process. I’ll respond to whatever the wall looks like.

Nicole Eisenman, Airport, installation detail, 1996 [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Nicole Eisenman, Airport, installation view, 1996 [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Nicole Eisenman, Airport, installation detail, 1996 [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

RDC: Can you give me an idea of how the installation actually changed?

NE: I added a mural to it and I built larger freestanding sculptural pieces in the room. At Jack Tilton, the piece was anchored up against the wall; in France it moved off the wall more. I added big ladders that acted like mountains; I used whatever I could find in the workshop of Le Magazin to build it out.

Nicole Eisenman, Airport, installation view at Grenoble, France, 1997 [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

RDC: When you approach your installations, there’s still a very formal viewing of a piece. It’s not like an installation that you’re engulfed in, that you walk around.

NE: I have mostly approached installations from the point of view of a painter, so it is always, ultimately, like looking at a painting as opposed to a more theatrical approach. However, the last big installation I did, at Rice University Art Gallery [in Houston], had performative elements, people in the piece, spaces you could walk into, live sound, lots of smoke and video.

RDC: Your recent exhibition at Entwistle Gallery in London also included a video, but it was clips you assembled from other sources. You make most of the other elements in your installations—would you ever make your own video?

NE: I have made a couple of videos for installations, but editing together borrowed footage from movies and TV is really in keeping with the sensibility of the installation. There’s a lot of junk that I’ve bought from stores and flea markets as well.

RDC: Do you consider the videos you make narrative?

NE: Yes. They illustrate ideas that help fill out an aspect of the installation. Or they function like wallpaper, setting a tone, underscoring an idea. For the Entwistle Gallery last May, I made a video with Charlie Atlas about swamps. It was a 10-minute loop made from clips of people going into various swamps and other swamp-related ideas—girls kissing frogs, that sort of thing. It was a central part of the installation, the monitor was sinking down into a pile of dirt in the middle of the gallery and covered with swamp life. The video needs the context of the installation. But it’s a riot to watch it on its own as well.

RDC: In the last few shows, you’ve begun to concentrate more on painting. You’ve developed a style that is less cartoon-like, more fluid, more perspectival, one could almost say more classical. Why has this change taken place?

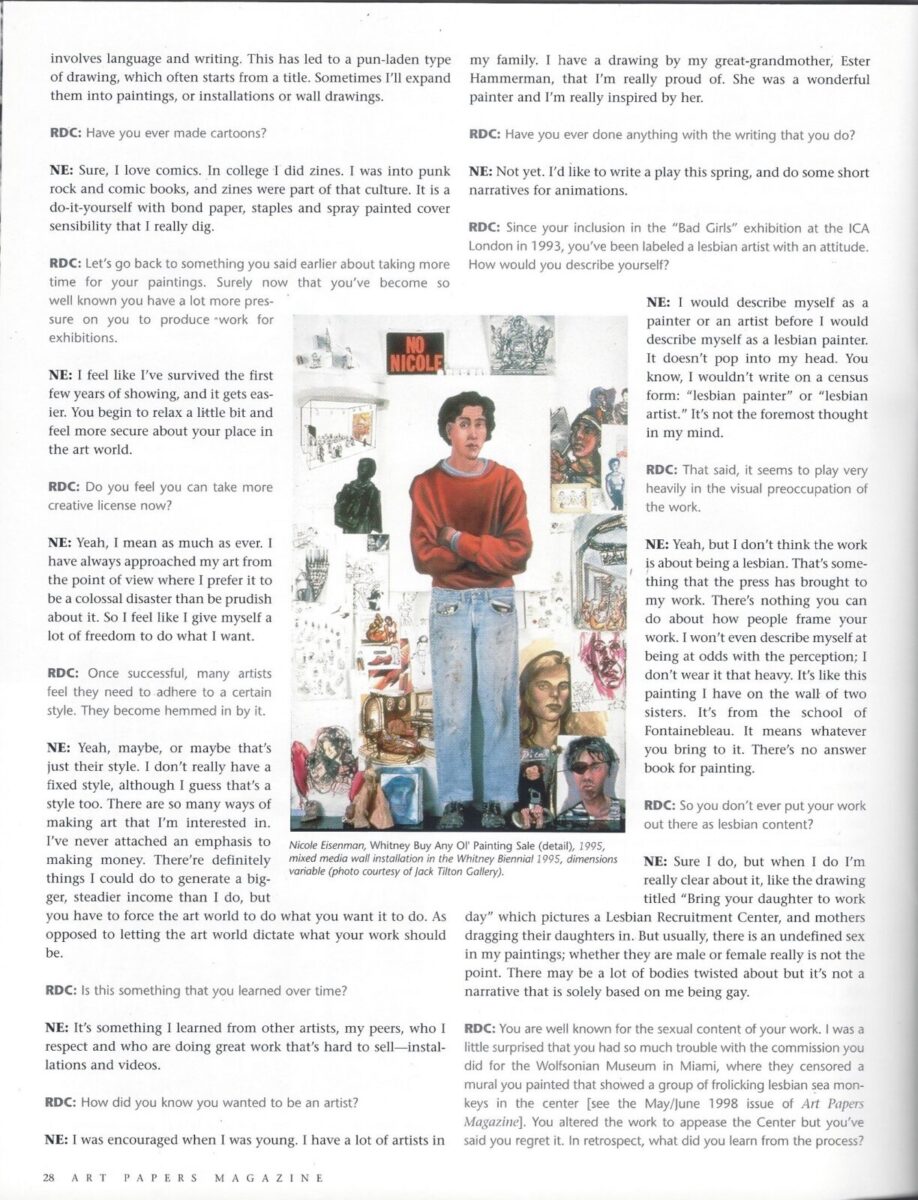

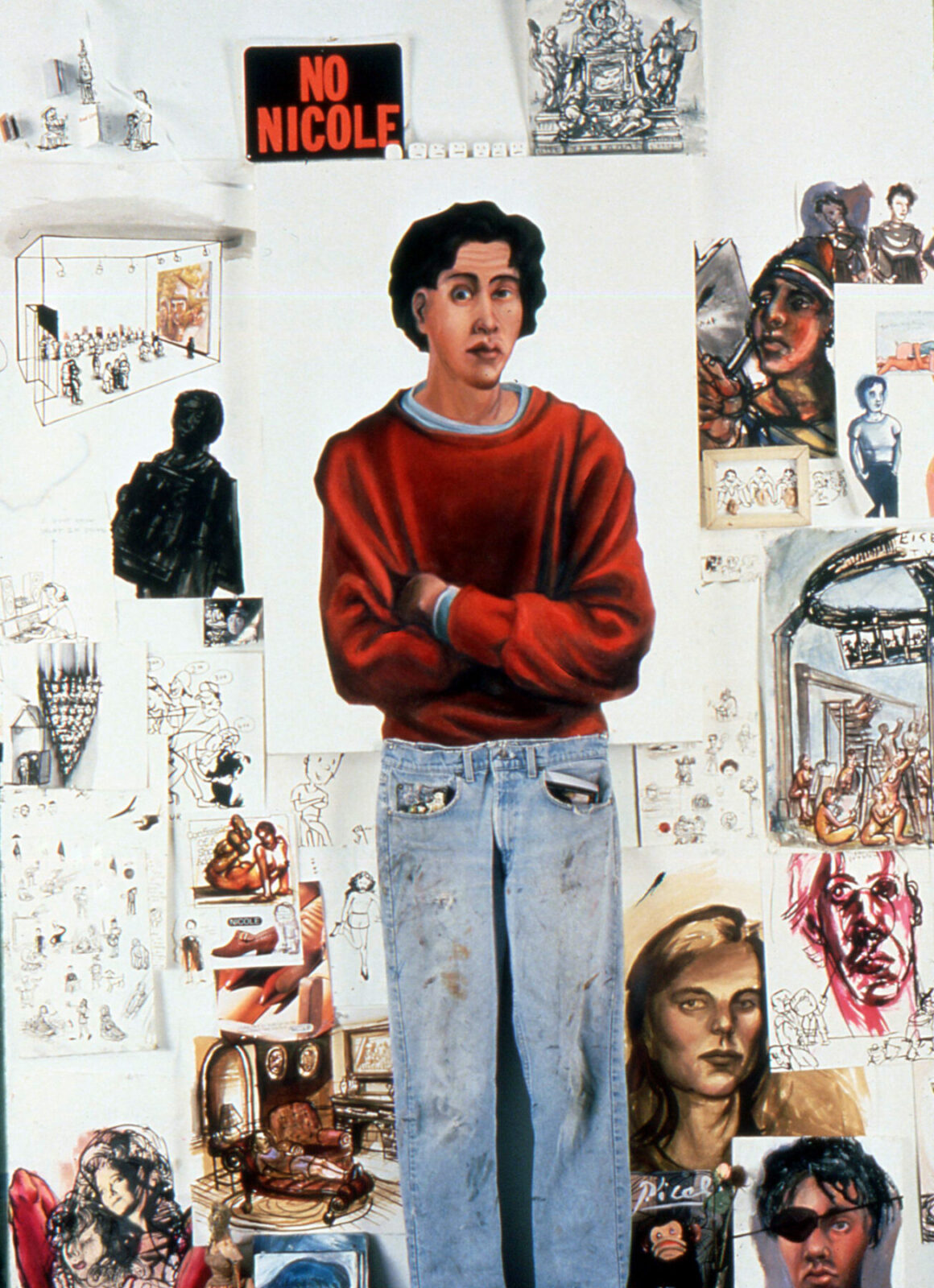

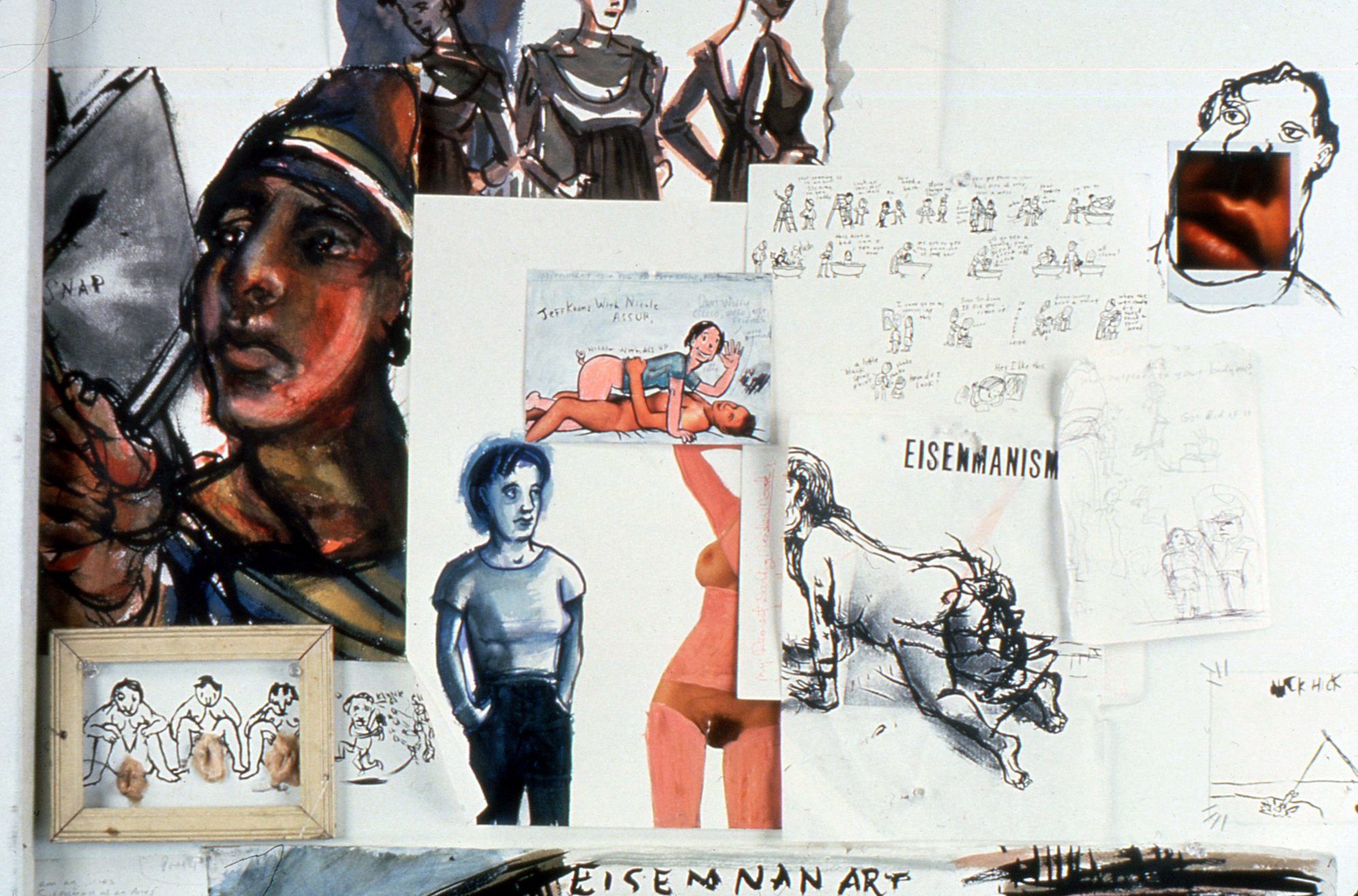

Nicole Eisenman, Whitney Buy Any Ol’ Painting Sale, 1995, installation view, mixed media wall installation in the Whitney Biennial, dimensions variable [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Nicole Eisenman, Whitney Buy Any Ol’ Painting Sale, 1995, installation detail, mixed media wall installation in the Whitney Biennial, dimensions variable [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Nicole Eisenman, Whitney Buy Any Ol’ Painting Sale, 1995, installation detail, mixed media wall installation in the Whitney Biennial, dimensions variable [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

NE: I think I’m just taking more time now to complete a painting. I don’t feel as rushed to turn out images as I did five or 10 years ago. I have been able to slow down and start doing full-palette paintings where I’m painting wet paint into wet paint again. There’s a full spectrum of colors and it’s a lot more complicated and ultimately the payoff is that you end up with a really rich object. In the past I avidly made lots of quick images sourced directly from my unconscious and fantasy life as drawings and monochromatic paintings. Recently, I have broadened these into more focused, richer, full-palette paintings.

RDC: But there seem to be two types of painting going on. There are now the multi-piece allegorical paintings as well as the one-line “zingers.”

NE: What you’re calling the “zingers” come from a more verbal tendency. I write a lot in journals and do a lot of cartoons, which involves language and writing. This has led to a pun-laden type of drawing, which often starts from a title. Sometimes I’ll expand them into paintings, or installations or wall drawings.

RDC: Have you ever made cartoons?

NE: Sure, I love comics. In college I did zines. I was into punk rock and comic books, and zines were part of that culture. It is a do-it-yourself with bond paper, staples and spray painted cover sensibility that I really dig.

RDC: Let’s go back to something you said earlier about taking more time for your paintings. Surely now that you’ve become so well known you have a lot more pressure on you to produce work for exhibitions.

NE: I feel like I’ve survived the first few years of showing, and it gets easier. You begin to relax a little bit and feel more secure about your place in the art world.

RDC: Do you feel you can take more creative license now?

NE: Yeah, I mean as much as ever. I have always approached my art from the point of view where I prefer it to be a colossal disaster than be prudish about it. So I feel like I give myself a lot of freedom to do what I want.

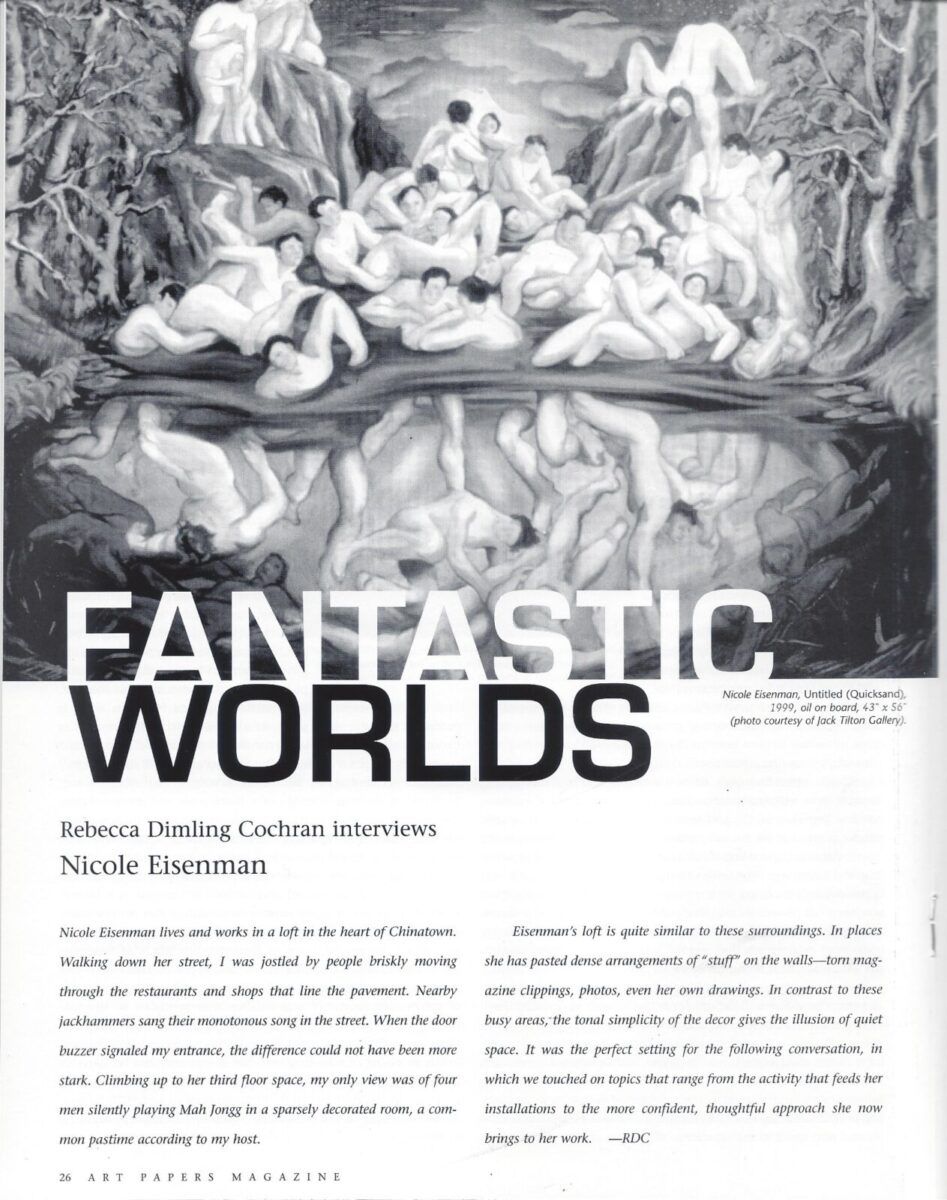

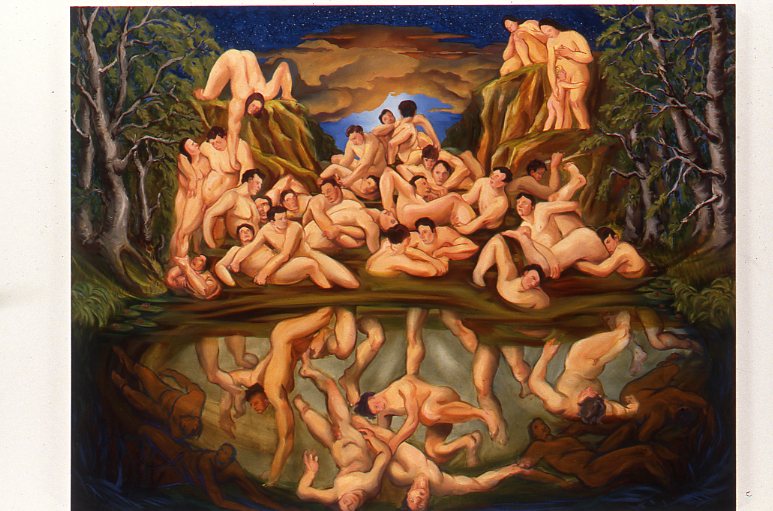

Nicole Eisenman, Untitled (Quicksand), 1999, oil on board, 43 x 56 inches [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

RDC: Once successful, many artists feel they need to adhere to a certain style. They become hemmed in by it.

NE: Yeah, maybe, or maybe that’s just their style. I don’t really have a fixed style, although I guess that’s a style too. There are so many ways of making art that I’m interested in. I’ve never attached an emphasis to making money. There’re definitely things I could do to generate a bigger, steadier income than I do, but you have to force the art world to do what you want it to do. As opposed to letting the world dictate what your work should be.

RDC: Is this something that you learned over time?

NE: It’s something I learned from other artists, my peers, who I respect and who are doing great work that’s hard to sell—installations and videos.

RDC: How did you know you wanted to be an artist?

NE: I was encouraged when I was young. I have a lot of artists in my family. I have a drawing by my great-grandmother, Ester Hammerman, that I’m really proud of. She was a wonderful painter and I’m really inspired by her.

RDC: Have you ever done anything with the writing that you do?

NE: Not yet. I’d like to write a play this spring, and do some short narratives for animations..

RDC: Since your inclusion in the “Bad Girls” exhibition at the ICA London in 1993, you’ve been labeled a lesbian artist with an attitude. How would you describe yourself?

NE: I would describe myself as a painter or an artist before I would describe myself as a lesbian painter. It doesn’t pop into my head. You know, I wouldn’t write on a census form: “lesbian painter” or “lesbian artist.” It’s not the foremost thought in my mind.

RDC: That said, it seems to play very heavily in the visual preoccupation of the work.

NE: Yeah, but I don’t think the work is about being a lesbian. That’s something that the press has brought to my work. There’s nothing you can do about how people frame your work. I won’t even describe myself as being at odds with the perception; I don’t wear it that heavy. It’s like this painting I have on the wall of two sisters. It’s from the school of Fontainebleau. It means whatever you bring to it. There’s no answer book for painting.

RDC: So you don’t ever put your work out there as lesbian content?

NE: Sure I do, but when I do I’m really clear about it, like the drawing titled “Bring your daughter to work. day which pictures a Lesbian Recruitment Center, and mothers dragging their daughters in. But usually, there is an undefined sex in my paintings; whether they are male or female really is not the point. There may be a lot of bodies twisted about but it’s not a narrative that is solely based on me being gay.

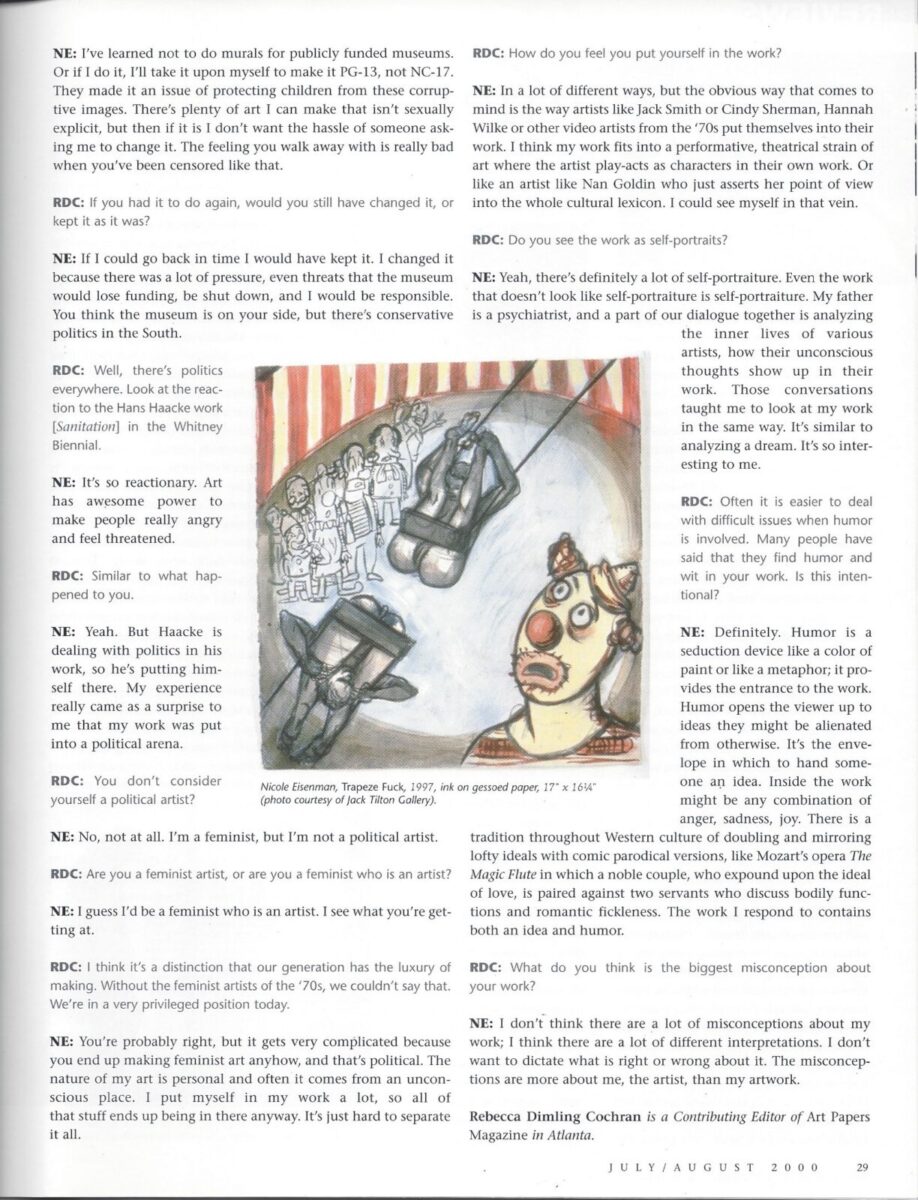

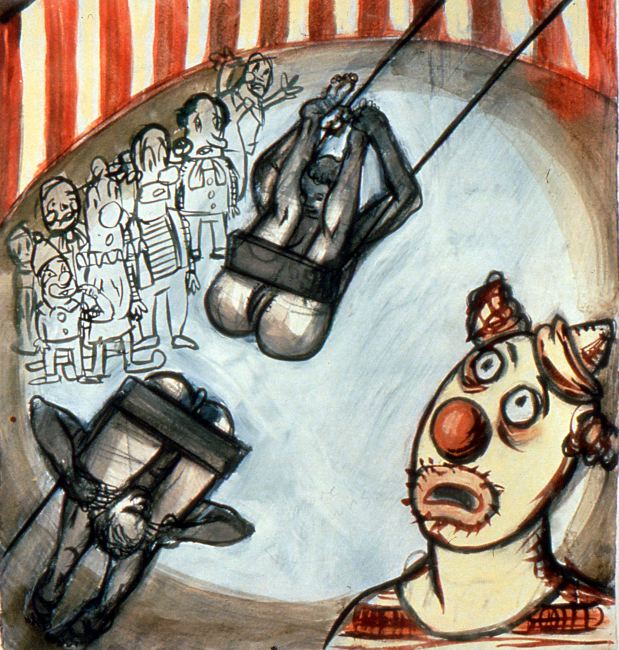

Nicole Eisenman, Trapeze Fuck, 1997, ink on gessoed paper, 17 x 16.75 inches [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

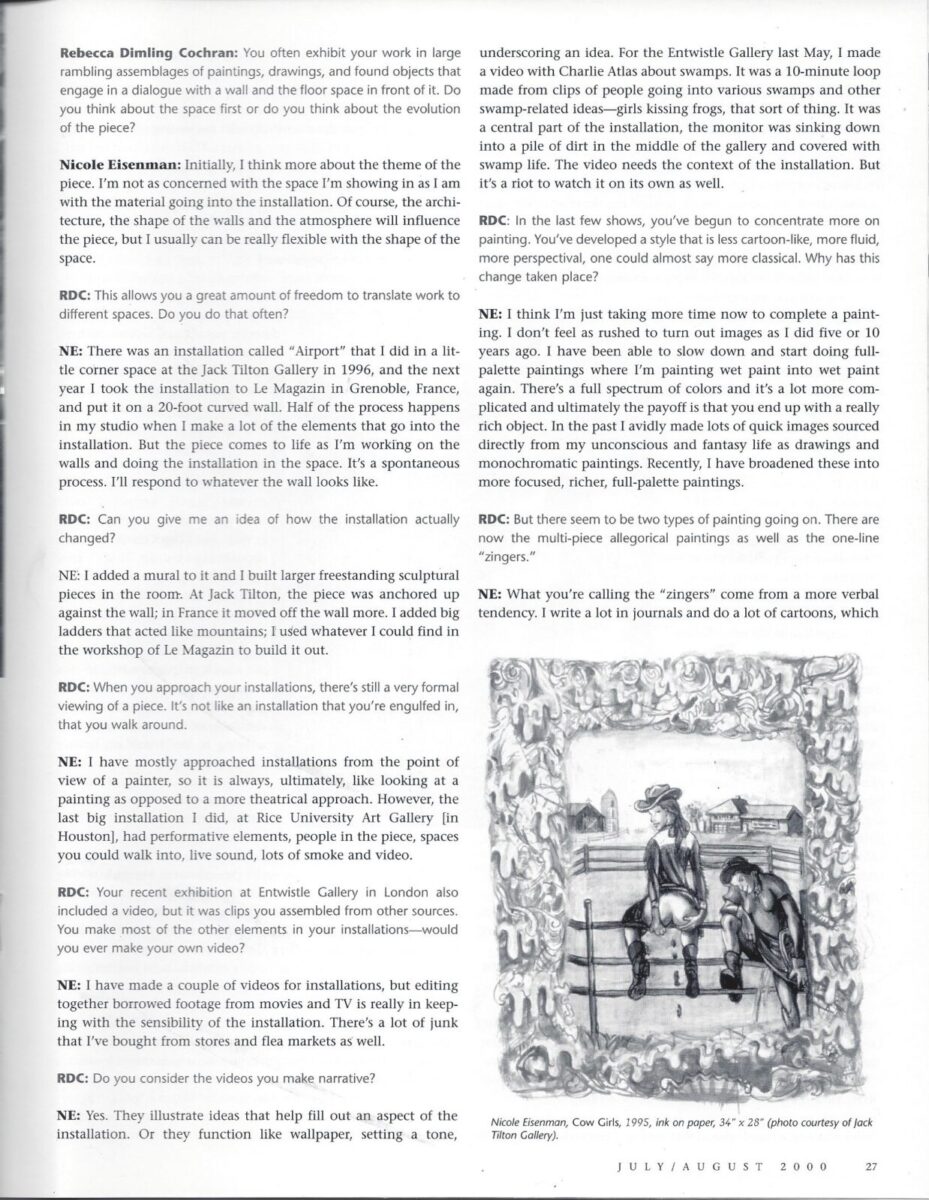

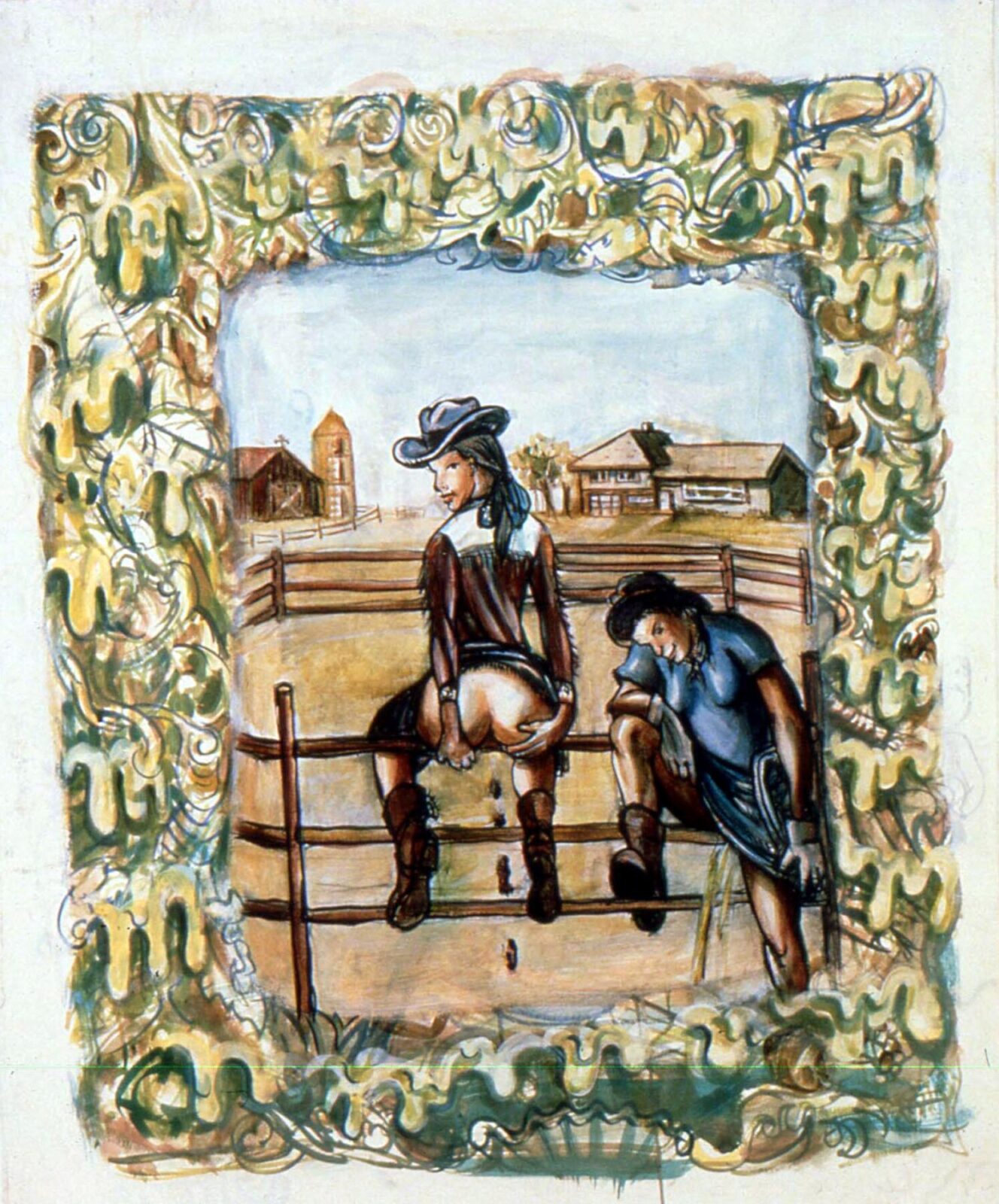

Nicole Eisenman, Cow Girls, 1995, ink on paper, 34 x 28 inches [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

RDC: You are well known for the sexual content of your work. I was a little surprised that you had so much trouble with the commission you did for the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, where they censored a mural you painted that showed a group of frolicking lesbian sea mon- keys in the center [see the May/June 1998 issue of Art Papers Magazine]. You altered the work to appease the Center but you’ve said you regret it. In retrospect, what did you learn from the process?

NE: I’ve learned not to do murals for publicly funded museums. Or if I do it, I’ll take it upon myself to make it PG-13, not NC-17. They made it an issue of protecting children from these corrup- tive images. There’s plenty of art I can make that isn’t sexually explicit, but then if it is I don’t want the hassle of someone ask- ing me to change it. The feeling you walk away with is really bad when you’ve been censored like that.

RDC: If you had it to do again, would you still have changed it, or kept it as it was?

NE: If I could go back in time I would have kept it. I changed it because there was a lot of pressure, even threats that the museum would lose funding, be shut down, and I would be responsible. You think the museum is on your side, but there’s conservative politics in the South.

RDC: Well, there’s politics everywhere. Look at the reaction to the Hans Haacke work [Sanitation] in the Whitney Biennial.

NE: It’s so reactionary. Art has awesome power to make people really angry and feel threatened.

RDC: Similar to what happened to you.

NE: Yeah. But Haacke is dealing with politics in his work, so he’s putting himself there. My experience really came as a surprise to me that my work was put into a political arena.

RDC: You don’t consider yourself a political artist?

NE: No, not at all. I’m a feminist, but I’m not a political artist.

RDC: Are you a feminist artist, or are you a feminist who is an artist?

NE: I guess I’d be a feminist who is an artist. I see what you’re get- ting at

RDC: I think it’s a distinction that our generation has the luxury of making. Without the feminist artists of the ’70s, we couldn’t say that, We’re in a very privileged position today.

NE: You’re probably right, but it gets very complicated because you end up making feminist art anyhow, and that’s political. The nature of my art is personal and often it comes from an uncon- scious place. I put myself in my work a lot, so all of that stuff ends up being in there anyway. It’s just hard to separate it all.

RDC: How do you feel you put yourself in the work?

NE: In a lot of different ways, but the obvious way that comes to mind is the way artists like Jack Smith or Cindy Sherman, Hannah Wilke or other video artists from the ’70s put themselves into their work. I think my work fits into a performative, theatrical strain of art where the artist play-acts as characters in their own work. Or like an artist like Nan Goldin who just asserts her point of view into the whole cultural lexicon. I could see myself in that vein.

RDC: Do you see the work as sell-portraits?

Nicole Eisenman, Exploding Whitney Mural, 1995, installation detail, acrylic and ink on wall [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

NE: Yeah, there’s definitely a lot of self-portraiture. Even the work that doesn’t look like self-portraiture is self-portraiture. My father is a psychiatrist, and a part of our dialogue together is analyzing the inner lives of various artists, how their unconscious thoughts show up in their work. Those conversations taught me to look at my work in the same way. It’s similar to analyzing a dream. It’s so interesting to me.

RDC: Often it is easier to deal with difficult issues when humor is involved. Many people have said that they find humor and wit in your work. Is this intentional?

NE: Definitely. Humor is a seduction device like a color of paint or like a metaphor; it provides the entrance to the work. Humor opens the viewer up to ideas they might be alienated from otherwise. It’s the enve- lope in which to hand someone an idea. Inside the work

might be any combination of anger, sadness, joy. There is a tradition throughout Western culture of doubling and mirroring lofty ideals with comic parodical versions, like Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute in which a noble couple, who expound upon the ideal of love, is paired against two servants who discuss bodily functions and romantic fickleness. The work I respond to contains both an idea and humor.

RDC: What do you think is the biggest misconception about your work?

NE: I don’t think there are a lot of misconceptions about my work; I think there are a lot of different interpretations. I don’t want to dictate what is right or wrong about it. The misconceptions are more about me, the artist, than my artwork.

Nicole Eisenman, The Whitney Buy Any Ol’ Painting Sale, 1995, installation detail, mixed media [courtesy of Tilton Gallery]

Rebecca Dimling Cochran was a Contributing Editor of Art Papers Magazine in Atlanta.