Obstacle Race

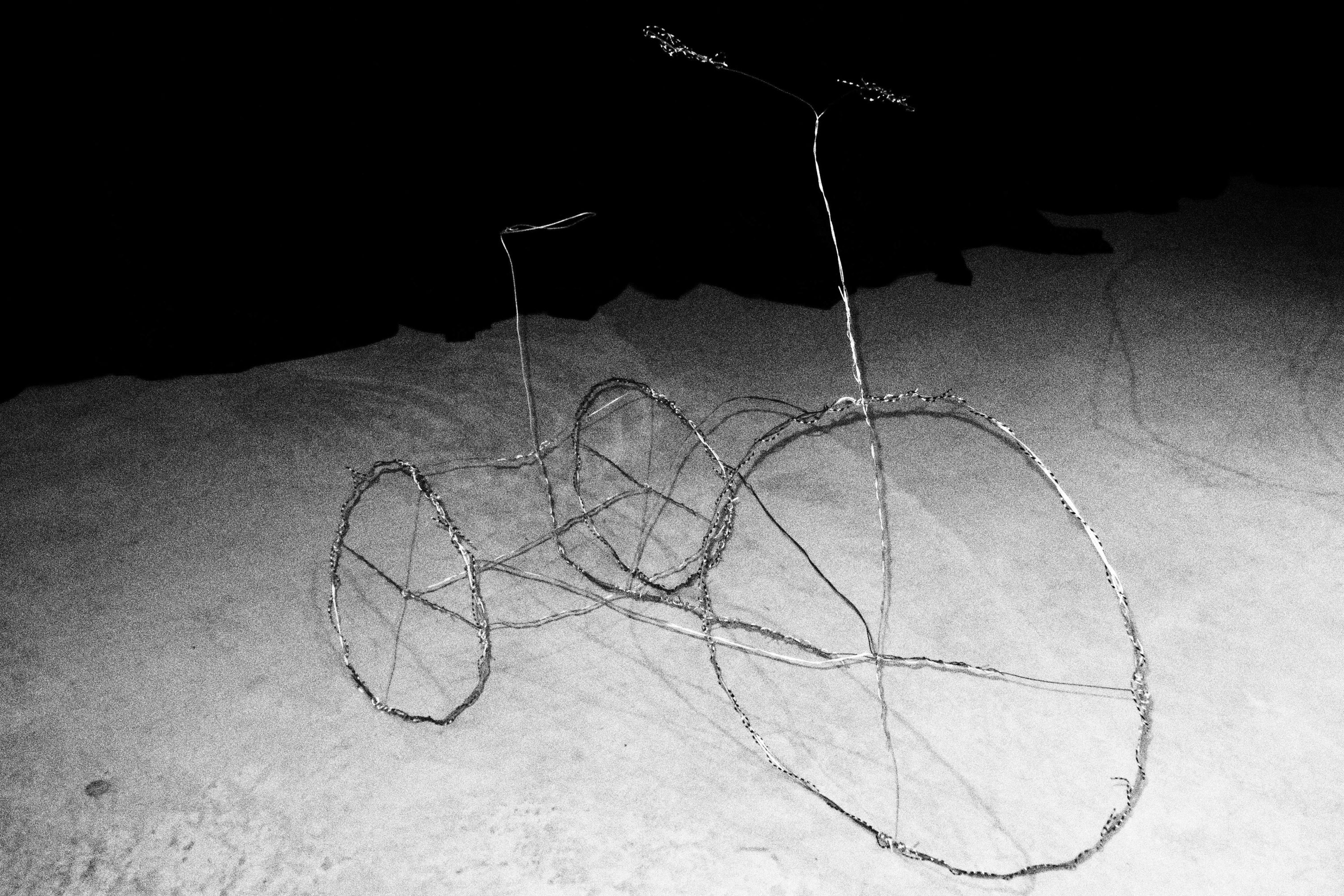

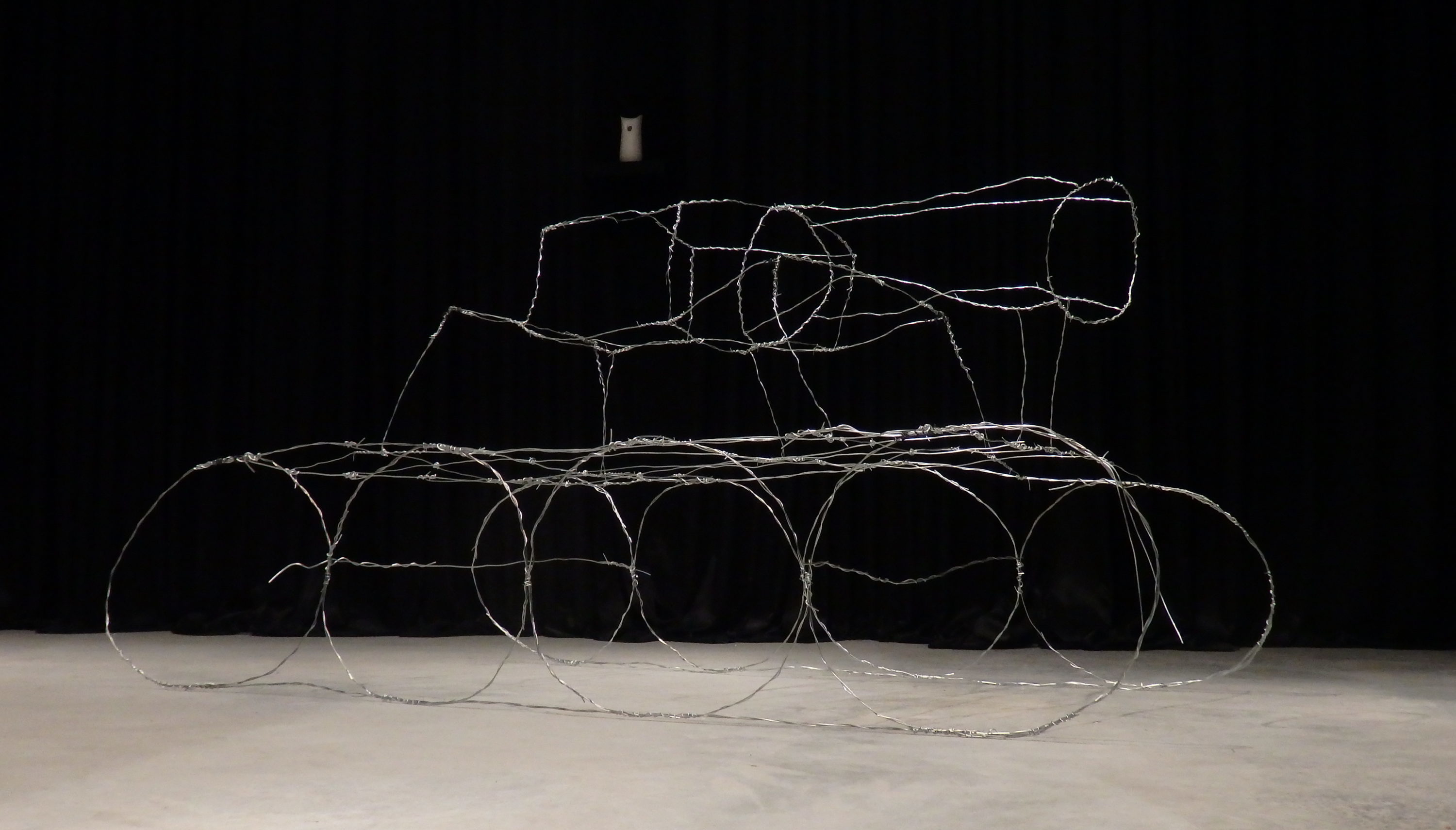

Amalia Ulman, Stock Images of War, installation view, 2015 [courtesy of Artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Share:

Egg Heels

I’ve never really written a piece on disability because of the conflicting nature of many perennial published writings and human bodies.

I never felt I could possibly commit to a deadline about something which is changing by the minute, or to form an opinion when I’m constantly learning about my body, either through research or the different ailments which surprise me whenever I’ve considered myself to be “healthy” again.

This will be an attempt to write about disability, but only about a very specific and quantifiable one, which is my injured legs. Even though bodies are a messy whole and not a clean sum of its parts, I will try to leave aside autism and any other problems which continue to contribute in making life difficult on a daily basis.

Maybe it is a good way to start the conversation about disability and visibility with the fact that I only feel confident talking about the things which I can back with scars, x-rays, and medical ephemera.

Trotting, Pedestal

I became disabled at the peak of my mobility. As a sort of wake-up call from a simultaneously successful and precarious lifestyle which had to come to an end whether crippled or not. Since then, many of those around me have both rolled their eyes whenever I asked for help or apologized profusely at the sight of my scars or cane.

As a visual artist, I’ve always been aware of the power of images, but the inability to portray pain made me suspicious of the belief that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” It is for this reason that we often use the adjective “unimaginable” when talking about extreme pain.

Pain is one of the hardest things for humans to describe and imagine. Once the pain is gone, it is hard for us, even those of us who have been through the highest levels of pain (think of the hospital scale, number 10), to remember the feeling of it once we are out of such agony—so willing are our bodies to recover from trauma.

When I think of visibility and disability, I think of cheap attempts at representation, things like showing the disabled in the media, such as including someone in a wheelchair in a fashion shoot. That, of course, is great, (it’s important to not represent only one type of body as beautiful) but not enough, and in a way it narrows down disability into what is already in the collective imaginary. The wheelchair, the cane, the crutches, the bandages. But there are also the things we can’t see. And let’s not forget fashion’s obsession with the strange, the bizarre, the new, which turns disabilities into a fetish.

When I think of visibility and disability, I have to ask myself when and where, under what circumstances. If we are talking about representation under capitalism, where everything has a price, including images, the representation of the oppressed and disadvantaged comes with a price tag.

If everything is transactional and everyone is looking out for themselves, why would anybody help someone with an invisible disability? Helping somebody who is not visibly disadvantaged only provides with personal satisfaction, not virtue signaling. It is a selfless act. Under capitalism it is rare for somebody to help without expecting anything in return. It makes sense then, that my most frustrating exchanges when asking for aid, have taken place in the USA and the UK.

Amalia Ulman, Stock Images of War, installation view, 2015 [courtesy of Artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Stone Steps

I am young and always try to look my best. This has caused me a lot of trouble whenever my scars are concealed under my clothes, or I am not carrying my cane with me. Once at Stansted Airport, running short of time I approached a woman guarding the deserted priority lane to the security check. I asked if this was the disabled lane and she directed me elsewhere, which turned out to be a long, crowded line. After 20 minutes of standing in excruciating pain, and realizing this wasn’t it, I went back to the still empty priority lane where the woman was now accompanied by another colleague. He confirmed that it was indeed the disabled lane and quickly let me pass while the woman who intentionally misled me looked at the floor. When I confronted her about it, she looked straight into my eyes and said, “You are not disabled.” On the verge of tears, frustrated and in pain, I limped toward my gate which was at the other end of the airport. I walk extremely slowly and can’t run. When I finally reached the gate, boarding was already over, and I wasn’t allowed inside the aircraft. The next flight was the next day. I had to spend the night on the floor at the gate.

You may say that I should have prepared better and arrived with even more time, that I should have asked for wheelchair assistance beforehand. As if people on the margins aren’t afforded the privilege of being complicated.

Early on, when I still thought I was on a path to recovery, I resented wheelchair assistance at airports because of that. Whatever it is that you are suffering from, airport assistants will sit you in a wheelchair. Despite my mobility issues, I love freedom, wandering around the airport, taking photos, making my own decisions, buying some food, sitting at a café….On a good day, by using the cart and faster priority lane, I could do well enough. Sadly, most of the times I’ve given up my custody to the airport, it has felt inhumane. Getting “parked” against a wall for 30 minutes is extremely depressing. So at the very beginning, before coming to terms with my limitations, which are now permanent, I tried, in vain, to fight for flexibility. And is there any other way to assist bodies not in a flexible manner? The best airport assistance has always started with the question “How can I help you?”

In case of doubt, assist those who claim to be disabled, those who ask for help. Contrary to popular belief, most people are not willing to put on a show. And if someone does…leave it up to karma to do its job.

You may be wondering why I’m talking about airports so much, but it is ingrained with my art practice. They say that a romantic relationship is marked by its beginning. As if the way that romance commences became a sort of contract for its structure, till its demise. My honeymoon stage with the art world was marked by deterritorialization. And I don’t know if it will ever change but, so far, it is a big part of how I earn a living, going places.

The Mind Hesitant

Some years ago, in a remote beautiful garden in northern California, I was sitting on a bench, reading a book, while a woman tended to the flowers. She was a beautiful woman in her 40s with impeccable style. She wore men’s work clothes, and a straw hat covered her blond hair, which was cut into a wavy bob. It was like watching Marlene Dietrich elegantly getting her hands dirty. I stared at her admiringly and at some point we started talking. I was there because of my legs, because of a crash and, oh, she had been in one, too. But she had just hit her head, and since then she suffered from perpetual migraines. That’s why she had this job as a gardener in exchange for accommodation. She used to be a professional dancer and teacher, but not being able to stand music anymore, she had to retire early and move far away, somewhere where people whispered and the only noise was that of the wind between the trees.

She looked gorgeous and healthy while suffering what for me would be hell on earth. Her disadvantages couldn’t be turned into a profitable spectacle. Her story made me feel grateful for at least having some scars to act as proof for my problems.

And this is why we must find ways aside from identity politics and aesthetics to comprehend these issues. No labels will ever be able to describe disabilities, which are as diverse as humans are on Earth. What we need is an ever-changing and fluid dialogue based upon trust and respect. When it comes to race, class, and gender it always seems taboo to ask questions, but I don’t see any other way to tackle health issues but through dialogue. Dialogue sparks empathy.

Amalia Ulman, Stock Images of War, installation view, 2015 [courtesy of Artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Brilliant Snail

With disabilities came a different perception of time—which is not the most fortunate thing to deal with when you live under capitalism. Throughout the past five years there have been many times when my leg pain has gotten me bedridden at the least convenient times, during install, or the day before a show opened….I will put it this way: during the last five years I’ve had a fraction of the time and energy most of my abled peers had, without any sort of privileges to compensate for it, earning the same (if not less) and spending more on medical treatments, massages, accessible housing and taxis. This is not something only I have had to deal with. Too many people around me have gotten burnt out, not being able to cope with the pressure the art world brings with it. Whether it is due to medical issues or class issues or both, it is heartbreaking to see talented people being left behind.

“If you are not feeling well, we will wait for you,” said no gallery or institution ever. In the long run, I don’t think a few months or even a year really makes a difference in the course of art history, as long as the work is good. But go tell that to an institution.

I wonder if the less you can comply with these rules due to medical reasons, whether physical or mental, is what pushes one closer to being an outsider artist. Outside of the circuit, outside of money, outside of recognition. Right where your ideas can be stolen, appropriated and monetized by wealthy/abled artists.

From Above

As an “emerging artist,” I didn’t feel my career was at all consolidated when I got into the accident that made me disabled, so I complied with every rule. As a woman, I feared being difficult. As a disabled woman I feared being left behind.

What I had imagined to be an inclusive and liberal atmosphere, was actually a very unequal structure. With very few exceptions, institutions would repeatedly tell me that they couldn’t cover extra transportation costs or accessible rooms because it wouldn’t be fair to the other, abled members of the panel, group show, or festival. In their logic, even though I was disabled and required extra funds and energy to be “normal,” to achieve same levels of productivity as the other participants, equality laid on the mere act of being included at all in the activity.

Even in the hospital, whenever I received calls from curators, no one ever asked how they could be helpful, instead everyone said the classic line, “I’m so sorry, I hope you get better soon,” as if wishful thinking and the ableist pressure to recover, to get well, was enough to solve the issue of inclusivity. But it is not enough, as anyone dealing with sudden medical debt can tell you. What is needed is direct action. There must be a structural change.

Seamy Systems

In Europe, or at least the Europe I experienced, with free healthcare, accessible education, and a system of grants, the trouble of being unprivileged seems lessened. One could focus on experimentation and art making without the distracting and destructive effects of poverty stress.

This is important for the poor but especially relevant for those with disabilities. To be able to receive decent disability benefits, healthcare, and housing eases the burden on having to prove and “perform” one’s disability for the camera—which sadly seems a must-do in today’s mediated life.

In the USA, lacking support, those with health problems have to rely on websites like GoFundMe, GiveForward, etc. which are simultaneously fueled by content generated for Facebook and Instagram, as if to support one’s case with moving, heart-wrenching graphic documentation. The better your online presence, the better a chance you have to cover your medical bills. As if photogenic-ness correlated with legitimacy.

Instead of health being a private affair, instead of having the choice to not participate in the marketplace of images, a lot of people with disabilities are pushed to presenting their issues very graphicly in order to elicit the empathy and support they deserve. This reinforces the assumption that their health issues are the only thing they have in their life, their only interest.

Personally, my health (or lack of) shapes my life and affects my art practice on a daily basis. I plan everything with regard to the amount of walking my legs can handle (40 minutes each day) and the amount of social interaction my brain allows me to do without exhaustion. This doesn’t mean my work has to be about these topics all the time. Yes, there are canes and wheelchairs here and there, but also pigeons, offices, and porn. That I performed able-bodied characters in my performances means only that I’m interested in a wide range of roles and topics—not that I’m less disabled. True artistic freedom relies on the ability to decide, with liberty, what one’s work is about. Just as white male artists have been doing for centuries.

With regard to disability and visibility, I think that, in today’s world of images, fortunate are those who have the choice to remain invisible—but supported and respected, without having to put on a show for others in exchange for being helped.

This project originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.

Amalia Ulman is an airport-based artist from Argentina with an office in downtown Los Angeles.