Itziar Barrio: Stella!—working on, and through You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid

Itziar Barrio, Stella a Roma, 2021, film and video installation, 4K, 19 min 40 sec [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

Share:

Itziar Barrio and I spoke about her experimental feature-length work, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid (2022). The 98-minute, three-channel video installation is currently on view in THE PERILS OF OBEDIENCE (PREMIERE), her solo exhibition at PARTICIPANT INC in New York.

You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid was filmed in multiple cities and makes overt narrative references to three films: A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), La estrategia del caracol (The Strategy of the Snail) (1993) and Accattone (1961). In the first episode, filmed in 2016 at PARTICIPANT INC, actors perform scenes from Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire in a workshop setting, against a white scrim. They are given on-screen direction by various theater directors and interviewed, both as the characters they play and as themselves. This mode of filmmaking and performing is utilized in each of the video’s three segments.

Barrio also traveled to New Orleans to absorb the energy of the play’s original setting. Spaces and objects (such as IKEA chairs, which the artist frequently uses in her works) play a vital role. The tenement-style architecture of New Orleans is echoed in Bogotá, where the second installment of the work takes place. The character Stella lifts herself out of the Streetcar narrative and is placed within the drama of the film La estrategia del caracol (The Strategy of the Snail), a story of eviction, communal living, and state violence.

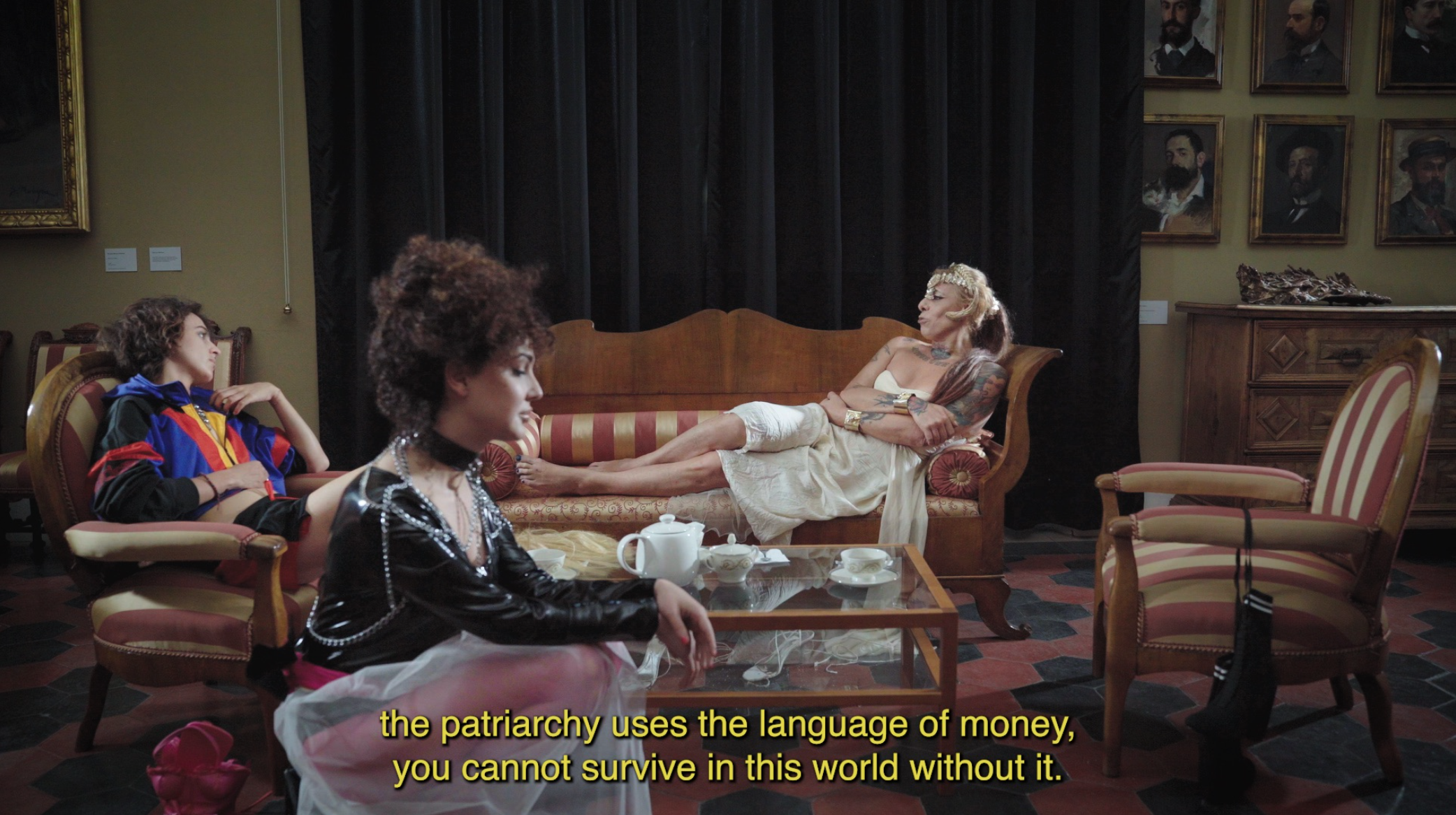

The epilogue takes place in Rome. Stella encounters the goddesses Venus and Minerva at the end of her wild ride as a sex worker and lover of the pimp Accattone from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film of the same name. In all the remixes, renditions, and reenactments, the power dynamics of labor, class, and interpersonal relationships are highlighted, and revolutionary manifestos and musical numbers are interposed throughout. Stella is played by a different actor in each city.

My conversation with Itziar took place before THE PERILS OF OBEDIENCE (PREMIERE) opened, so I had only viewed the video on my computer. I was excited to focus on You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, the 12-year process of its creation, and its themes of agency, sex work, and queerness. The video asks how we might shake up the dominant narratives that steer our lives while revealing the collaborative possibilities of artmaking via cinematic form.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

Jillian McManemin: The film is composed of disparate methods, usages of film, text, and improv. How did these pieces of media that you utilize get accumulated?

Itziar Barrio: I guess it is part of the organic process of making art. The actual journey of making is what takes me to things …. The films I chose to work with always have four characters: one is a leader, somebody that wants something; then we have an anti-leader, somebody who is going to make that impossible; then there is the soldier that helps the leader in that goal; and the navigator that goes in between. In the case of the pilot that took place in Bilbao, my hometown, I didn’t use scripts. Then I looked for films with iconic scenes, and I would look for those characters.

The idea of contemporary mythology is important to me. In North American culture, when Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire screams “Stella! Stella!”, it’s an iconic scene. Or, for example, Basic Instinct [1992], with the very iconic scene of Sharon Stone crossing and uncrossing her legs. The same, no? A small gesture that signifies a lot.

JM: Both examples were super disruptive in their time. Basic Instinct blew everyone’s minds …. I guess it’s the same with Marlon Brando. His raw sexuality was shocking to people. That’s helpful to position these archetypes as a starting point for your practice. You’ve also mentioned the Stanley Milgram obedience experiments in the early ’60s as being a jumping off point and inspiration for the beginning of your project. Is that where the character archetypes that you work with are stemmed from?

IB: The project really started as an investigation of power dynamics. I approached the project as a constructed situation. I have the characters. I have the furniture, which is always IKEA. IKEA is another dominant narrative, right? Another contemporary mythology? Then, thinking about power dynamics, the Milgram experiment … proved how people ended up doing things even if they did not want to do them, because they were ordered to.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

JM: The people conducting the experiments were trying to make sense of genocide.

IB: [The Milgram experiments] give the title to the entire project. The title is a little bit like, you know, when you have a band when you are a teenager, and you always wish you could have another [name]. I feel like that sometimes. The project has grown in many other directions. The first challenge was to make a film without a storyboard or a script.

JM: You have staging, and then you have people interviewing the characters, and then the actors get interviewed. It is like all these vantage points—reenactment, autobiography—which I found incredibly interesting and strenuous. You have these moments when actors are performing, and then they are giving “real answers” about their “real lives.” It was funny—I had this expectation that you would be in the film more than you are. You made a film that is investigating its own filmmaking, but then, as the director-character, you are only a very slight specter.

IB: That is an artist’s decision, you know? The filmmaking, as a performance, is a way of showing labor, the power dynamics involved in the making of a film, and the means of production. Those are obsessions in my work. I always see myself—not necessarily as removed, but when people come to see the performance, they see me working as the director, and I’m very much on the side. I am directing the cameras and the production. You see the theater directors more, and that is part of the orchestrated plan. This is what I call the constructed situation. I am just busy directing the film. I am not going to be performing. I delegate. I am not directing the actors. You only see me talking because we have a problem with a camera.

JM: Pasolini is such an iconic filmmaker, with an iconic personality. I saw you in that one scene in Rome, and you are really working with all the equipment. There is so much about labor, work, and power dynamics, but the films that you have stitched together show queerness throughout. You have Tennessee Williams. You have the character Alan Grey, Blanche’s first husband, who [in Williams’ play] killed himself after being confronted about having a homosexual encounter. Then, you have this situation in Bogotá, where people in this communal living situation are being evicted by the state. Then you have Pasolini, who was killed. Queerness and violence seem to be a remarkable thread throughout the entire film.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid (screenshot), 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

IB: They naturally emerge. Pasolini doesn’t talk about it, but we all know that he was gay. Tennessee Williams decided to talk about these communities and suicide. It is part of the dominant narrative that I am trying to rewrite. Violence goes along with a lot of things in life, no? But I guess my work is queer in the sense that I think in those parameters of identity.

JM: The film doesn’t exactly offer a queer utopia, or an emotionally satisfying solution to all of these swirling problems. It’s more complicated. I am curious about the politics behind it. The film is repeating over and over that transparency and the ability to speak can be a revolutionary act. There were parts that felt devastating because there wasn’t a solution or proposal. We’ve previously talked about manifestos. What are your thoughts on the politics that you put forth in the film—with the usage of manifestos and revolutionary texts?

IB: I am obsessed with riots, too, and historical events that disrupt. They are possibilities for change, for new possibilities. My work in general, and specifically this project, is about rewriting dominant narratives and trying to bring in new ones. Manifestos are there for that. I used text from [Donna Haraway’s] “A Cyborg Manifesto” in the video. Manifestos look to the future, even if they are naïve or silly. I like the imperfection, or even the failure, because it is sometimes the only way that we can find things out.

JM: I want to talk about Stella and the evolution of Stella within this project. She becomes a vessel for every question that the film asks. I was thinking of it in terms of scale, with Stella and her location and environment. She goes from being in A Streetcar Named Desire, in this tiny apartment, this domestic violence and familial situation that is really claustrophobic, to the next film, where there is polyamory happening, and communal living. Then, finally, she arrives in Rome on this heavenly plane, where she has gone through even more turbulence, as the ex-lover of Accattone. I want to hear a little bit about this ascension and scale shift, as far as agency for this character is concerned.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

IB: Focus on Stella and you can find a lot of the characteristics of how I work in this piece. I mentioned the character-archetypes being important, but also they were part of a sub-proletarian class. I’m always very interested in class and underrepresented communities. I decided to put her in the context of La estrategia del caracol in Bogotá. The architecture [in the two films] is similar: tenements. Not exactly the same, but [involving] communal living and the frictions that come with that.

We see Stella going through different bodies, languages, and cultures. I think this hits at the core of my ideas around identity. Then in Rome, as you mentioned, we see Stella extracted from Accattone by Pasolini. Stella is a sex worker. Dissent is very important in my work, too. I like breaking the rules. Maybe going back to your reflection on violence and queerness in my work—I’m not going to give a solution, but there is something possible in the agency that we all have to rewrite narratives. There is an agency in us. I am trying to take that, as an artist, and I am trying to talk about that. That is my work.

JM: Absolutely. As a sex worker, I was grateful for how you handled this material. With A Streetcar Named Desire, you have love, you have sex, you have class, you have money, and a power struggle. Sex work holds all of this in a very intense way. It makes sense that your film explicitly talks about sex work, because within sex work you have relational dynamics, you have the state. And race and class lines are intense in the industry in a way that people don’t understand. Sex work is also always adjacent to and interwoven with queerness. In the film, when Minerva and Venus are arguing about whether sex work is about the sex part, or the work part, it felt like we can’t even really get to talking about these issues if we can’t agree on any definition. Your film is formally super fractured, and trying to analyze itself, but I think that the ethos of the film is at least trying to get to some definition about what you’re doing as far as labor is concerned—as an artist or filmmaker.

IB: It’s also not a coincidence that the video [ends] with Minerva, the goddess of intelligence and strength. She reflects on the construction of reality and making. Lola Kola, the performer, says that she prefers life, instead of film. She says reality is beautiful: the possibility of movement, the possibility to construct things, right? There is something here that relates to hope and the idea of constructing narratives.

We are embedded in this capitalist society, where we do labor for money. But suddenly we judge others and so on, right? Our bodies are always being exploited, if we think about labor.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

JM: There is a bit of text: The consequence of the wage relationship, the systematic alienation as the worker …. The whole film gets blanketed with this statement.

IB: That is part of “A Cyborg Manifesto” by Donna Haraway. [The film] is a lot about different ways of being in this capitalist society. I think a bit of Marxism is needed, no?

JM: I used to have these ideas as a sex worker and Marxist, like, if I’m identifying as a sex worker, then I think every person should identify with the way that they make money—especially in the queer community—as a political act. But people don’t always want to be defined by how they make money, so it gets slippery. Minerva, in the Rome part of the film, mentions the Red Umbrellas, a real organization, and talks about the liberation of sex workers. I was like, What does that even mean? I can imagine better conditions, or a better conversation, but this strong word, “liberation”—I was so thirsty to grasp what that meant.

IB: That scene happened so organically, working with Federica Tuzi, one of the screenwriters. I have to acknowledge the theater directors, Cristina Vuolo, Charlotte Brathwaite, and Julio Correal: we co-wrote, and had a lot of conversations. We had Minerva talking to the camera as the character, and also as herself. The subjectivity of the performer is very important in the work.

JM: Through a relational process, you are kind of trying to be the opposite of Oz—a looming director who is masculine and very forceful. I’m curious, because this process has been going on for about 12 years—is that correct?

IB: Because of Covid, we ended up postponing the premiere twice.

JM: How much of this project is woven into your identity as an artist? I think about the life of an artist, and how what we make determines how we interact with the world.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid (screenshot), 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

IB: I can’t think about it all, but I’ve been doing that recently, because of the archives. We are making a website [for the project’s archives]. It’s emotional. [This work is] the biggest investigation that I’ve done. Another aspect is that the technology has changed. In Bilbao it was basic HD in 2010, And the final [shoot] is 4K, in Rome.

JM: Does showing the project in its full form feel like letting go? Or do you just feel like it is enmeshed into your practice, so there’s no separation?

IB: One part of me is like, I need to finish this! In each location, the crew is from the place. It is very localized. I think it makes a lot of sense to work with people that are a part of a specific context and culture. It’s good to wrap things up; it is very exciting for me. Seeing this reaction, even yours just now, is adding to the conversation that I have with the piece myself, too. I don’t even see what it is about anymore, you know?

JM: It’s funny, a proposal of transparency as being something that can get us toward truth. Then, as the artist, you’re like, “I’m blind.”

[both laugh]

IB: My work can be super conceptual or rational, but what people might get out of the film, I still don’t know.

JM: I think it is going to be really different for everyone, because of people’s individual relationships to the media that you put forth. Whether or not someone has any interest in Pasolini, in A Streetcar Named Desire, or has a relationship with any of the locations you travel to. The moment, “Stella!” is important to me, because I am an American, and I love film. I saw Streetcar when I was really young. For the film in Colombia, I had to do more research. [This experience of familiarity] might be swapped for somebody else. Something iconic can happen in another area where I might completely miss it. People are going to have different reads based on their history as sex workers, as filmmakers, as queer people, or as not any of these things. There were moments in the film when I got emotional, and I was like, Oh, this is hitting something about my personal history. Cinema is an emotive force. There were also moments where the actors were speaking about their lives, which I found really wonderful. Who plays Stella in Colombia?

IB: Yes, Endry Cardeño.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid, 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

JM: She was talking about being mistreated and objectified as an actor , and her evolution as a performer in the ability to advocate for herself. I was like, Oh yeah, I totally have known this person, or have met someone like this person, but in a different context.

I also want to talk about the scale, as far as how many countries you filmed in.

IB: I really wanted to work with different groups. I didn’t know where it was going to take me, honestly. Then the organic and the poetry comes along because I always want to have that in my work and in life. Bogatá was very personal. I had this connection with my gallerist Margarita Rodriguez Rincón, director of Rincón Projects. I was already working with her, and we are still working together. I was not like, I need to do it in another country or in another space.

JM: So it merged with and emerged from your life .… There is a tumbling through life, and then art gets merged into it.

IB: Labor, too. I’m very obsessed with labor and with the means of production. This collaboration affects the people I work with and that is part of the project. When I finished Bogotá, I was like, Of course the story is not finished, it is not complete. I didn’t know if there was going to be another stage.

JM: I love that it ended up in Rome. You are talking about building these archetypes and trying to understand them. Then, from these archetypes of men and women, it’s like, No, no, let’s just talk about these goddesses .… It got bigger and bigger, as far as the effects that these archetypes might have on the way that we conceive of things. There were also these moments where you use music. The last musical scene was the goddesses singing “Labor Union Sluts” after grasping for answers about sex work. They were like, Okay, maybe we should take a break and sing this little song. I was wondering about the musical interlude. I think that music holds energy similar to that which a manifesto can hold.

Itziar Barrio, You Weren’t Familiar but You Weren’t Afraid (screenshot), 2022, film and video installation, 3-channel HD, 98 minutes [courtesy of PARTICIPANT, INC]

IB: That is what contemporary mythologies are all about. Music is huge in that. The first stage, in Bilbao, I ended up remixing “Sweet Dreams” by the Eurythmics with Keith Milgaten. That is an iconic song. Music is very important .… For me, they are kind of these soft transitions into other themes, or they bring a moment, or intervene. In Rome it happened very organically. One of the performers is the singer too.

JM: You shift us toward desire after such hard concepts—after talking about all this complicated shit, you turn to music to provide relief, so we can hold these thoughts at the same time as we feel pleasure, feel sexy, laugh. This is important, because if you are telling someone something, and you really want them to listen, and then you make them laugh, it’s a huge power move. People are going to listen to you if you’re charming. I felt like the goddesses were kind of playing with this idea.

IB: Music is very connected with subculture, and a lot of my work is about that too. I was lucky that [the actors] were [also] singers. This goes along with my usage of fiction and nonfiction and [the actors’] own subjectivity and passions. Desire is very important in my work, the sense of humor and lightness. I also love music. Rhythm is important when you are making a film and editing. In Rome we see Stella playing the piano. That happened spontaneously. She was so generous, and it was all so magical.

[In the film, the characters] Minerva and Venus—we haven’t talked about patriarchy. They are talking about it, and that moment where they decided that we can actually be together, sing, talk, and feel this: There is also hope there, Jillian! In the end, when they come together.

JM: I do feel like it is incredibly hopeful! I also loved the idea of a sex worker being like, I am in this great position, because I am being flanked by these two goddesses. It gave the archetype of a sex worker this elevation.

What I was saying earlier is that I don’t think that the film necessarily offers up a utopia, which to me feels like a closed environment that cannot exist. The proposal of a utopia doesn’t do anything to liberate anyone. I would rather be hanging out with the cool sex workers and arguing and singing. That sounds better.

IB: The last scene in Rome is an epilogue. In Bogatá I replicated the final scene in La estrategia del caracol where they ended up going up a mountain with their fictional house. I used that scene but with Stella, she’s just going up a mountain to get to this very fantastical place with two goddesses.

The locations and the empty spaces by themselves [are] very important to my practice. I mean empty spaces as not having human bodies present. I usually approach them as characters too. There is that house scene with the fountain that is replicated in the three places. I want to say that, because it is important in the sense that we were just talking about people … we have to talk about things. There happen to be spaces that have a similarity. There might be a little sci-fi attached to all of my works. I am not a sci-fi artist, but it is there, a little salt of sci-fi. It is not just Stella traveling through different bodies, languages, and cultures; these spaces are also interconnected, and we don’t know how or why. I was able to film the house in New Orleans that supposedly inspired Tennessee Williams to write A Streetcar Named Desire.

JM: I was thinking of the house in Bogatá as a character that gets fought over and invaded, and shots are fired to get the eviction happening. It’s really this space that is being contested and pulled back and forth. What should this space be used for? Who gets to decide what the space gets used for?

IB: Yes, that is actually a very important thing. It is not only about humans, but it is also about our spaces. Time and space get resolved in that way, in the film.

JM: The show will have sculptures, as well, that are going to have varying degrees of agency, I assume.

IB: They’ll have agency, like anything else.

Jillian McManemin is a queer multidisciplinary artist and writer whose work has appeared in BOMB, Hyperallergic, Art-agenda and The Brooklyn Rail, among other publications. She has performed and presented work at Anthology Film Archives, MetLiveArts, The Poetry Project, Dixon Place, Invisible Exports, and the Knockdown Center. She recently founded the Toppled Monuments Archive, and she is working on her first book, Sculpture Kills. She is based in Brooklyn, NY, and is currently the exhibitions manager for the estate of David Smith.