Tamia Alston-Ward’s

Le Déracinement (The Uprooting)

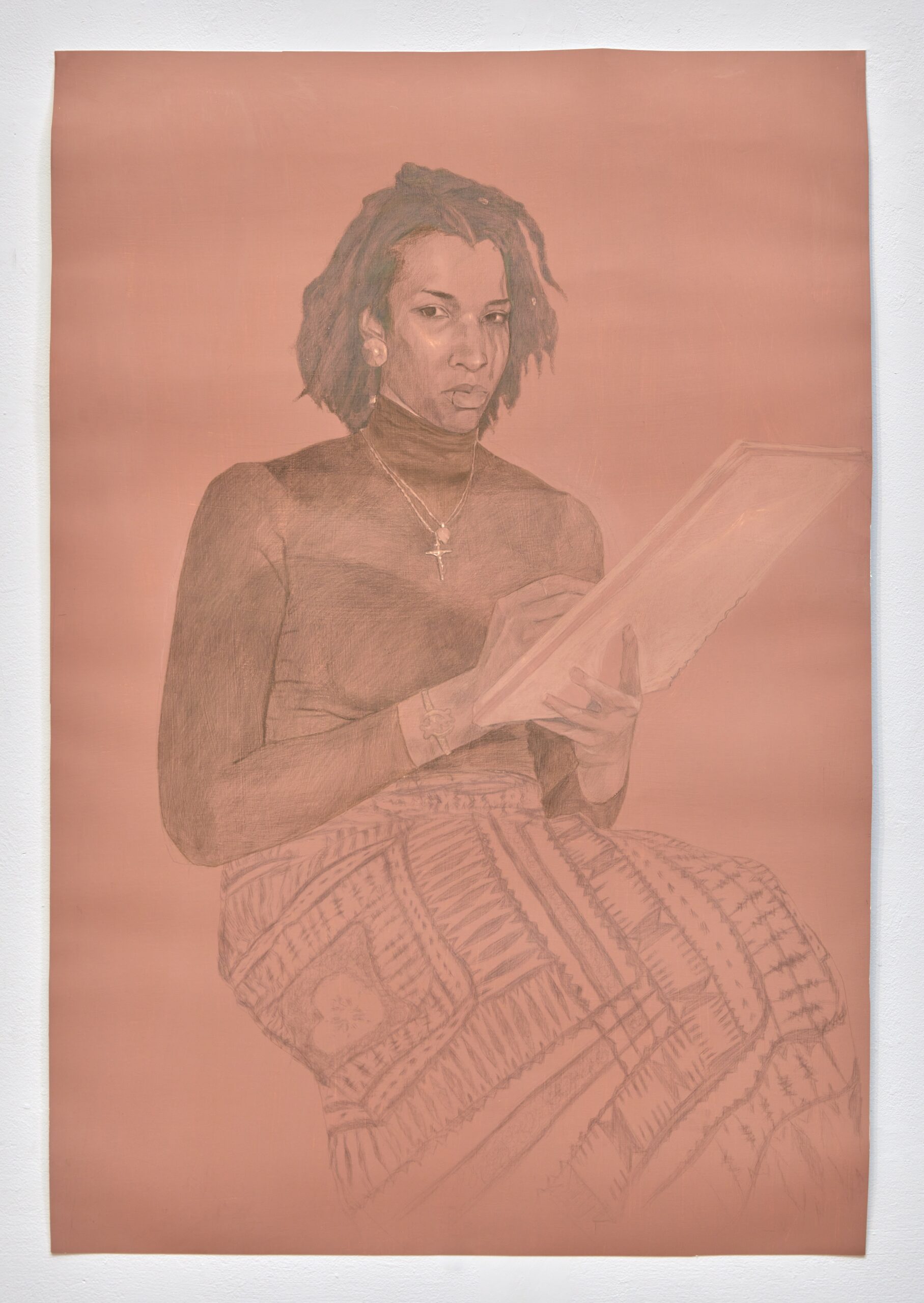

Tamia Alston-Ward, Le Déracinement (The Uprooting, installation view, 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

Share:

American material and visual history are interconnected—the two cannot be separated. This fact is made apparent in Tamia Alston-Ward’s solo exhibition at Welancora Gallery in Brooklyn. The gallery nestles between the borders of adjacent neighborhoods Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy. Le Déracinement (The Uprooting) blends painting, drawing, and readymade objects that are categorized into sections including mammies, other problematic figures, genre scenes, and nonobjective paintings on wood panel.1 The term déracinement means uprooting in French, which implies an act of taking something from its original home or context. Within this exhibition, the Philadelphia-based artist looks at how colonialism, personal and collective identity, and removal are shared by American and European history. Alston-Ward uses the Barnes Foundation’s Art of the African Diaspora collection as her case study. The collection primarily consists of probably stolen objects from the African continent. The Barnes Foundation was founded by Albert Barnes in 1922. Its original building was in Merion, PA, but the foundation is presently located in Philadelphia. Barnes acquired his African art collection through Parisian dealer Paul Guillaume, and that is how the “fetishes” came to be in his possession.2 These objects were extracted from the African continent during the early-20th-century Scramble for Africa. The collection is made up mainly of utilitarian objects meant for an array of uses, such as protection of one’s home or religious rites. Through Alston-Ward’s juxtapositions, she sets the ground for a critical look at American history. For me, the mark of excellent art is consistency throughout mediums. I saw that consistency embodied within this exhibition. Alston-Ward’s aesthetic and intellectual prowess beams through the show.

Tamia Alston-Ward, Le Déracinement (The Uprooting, installation view, 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

Welancora Gallery is housed within a beautiful brownstone owned by Ivy N. Jones. She welcomed me into the space and walked me through the exhibition. She is kind, and we discussed various topics at length. It’s refreshing to enter a gallery space and be engaged by the owner in such an authentic way. It’s refreshing and important to encourage intergenerational dialogue. History itself is intergenerational; to properly interrogate it, we must use varying vantage points.

I am appreciative of art that makes me—that makes us, as a people—think about history and assess our relationship with it. Culturally relevant dialogue and exhibitions are necessary to ensure that stories are continuously told in a freshly accurate light. The walls of the gallery are tall, regal, and exude a quiet that complements the exhibition’s seriousness. As you enter the vast space, you encounter small sculptures. Several of them are mammy figurines. Others depict small children who are adultified and sexualized in their appearance. All of their features are obscenely exaggerated. These sculptures are then painted in egg tempera, with 24K-gold decoration.

Tamia Alston-Ward, Le Déracinement (The Uprooting, installation view, 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

Stereotypes hurt. The mammy is one of the most iconic and common pieces of American material culture and imagination. In Mammy #1–5 (2022), each painting depicts versions of these traditionally red, black, and white sculptures. Mammies are typically shown as larger, darker-skinned women in domestic clothing. In narrative form, they are jolly and always ready to serve. She is a complex symbol of care and nurturing within the American racial imagination. In Alston-Ward’s Mammy #1, she holds a bobbin of thread, and in #5, she has a clothes hamper at her side. Her countenance shows an eagerness to help. In #6, she wears a blue dress with a floral apron. In this sculptural form, she is a cookie jar. The presentation of the Black woman in the United States is historically attributed as either the caregiver or the whore. There tends to be no in-between. Any in-between space would mean that you—a Black woman—were not working. Rest does not exist for you. Cuzzo #2 (2022) depicts a jet-black child sitting on a gray pot. The child firmly clutches a large wedge of watermelon. The figure in the original sculpture has their bottom exposed. Cuzzo #1 shows a child in a Josephine Baker–style outfit. Her arms are held behind her head, further accentuating her breasts. Layered necklaces drape her chest, and her eyelids are painted blue.

Tamia Alston-Ward, Le Déracinement (The Uprooting, installation view, 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

American material culture cannot negate the racist legacy bred within itself. It is in the mammy cookie jars, the statuettes, and in metal. In this show, Black women and womanhood are highlighted overtly, in both the material and the presentation. Black men, maleness, and manhood are acknowledged in a different way. Census #2 (2022) is a drawing composed with nickel, steel, lead, silver, and 24K gold on prepared paper. Census #2 shows a young man playing basketball. He appears in two different stances. In both, his back is toward the viewer. Within her paintings and drawings, the artist uses metal as a means to reference (implied) value. The 24K gold is meant to convey the pricelessness of Black people. The other metals correlate to both the Barnes Foundation’s objects and weapons that take the lives of young Black men. These material choices speak to power: the power of physical violence and the violence of having history removed, erased, and placed within oppressive contexts.

Tamia Alston-Ward, Le Déracinement (The Uprooting, installation view, 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

Tamia Alston-Smith, From: Nana, 2022, 24K gold, glitter, steel, nickel, silver, bronze, copper, brass, casein ground, mummy brown pigment on prepared paper , 51 x 34 inches 2023 [courtesy of the artist and Welancora Gallery, New York]

When an exhibition leaves me with a lingering emotion, then I feel the art has done its job. I’m still seeking where to place my emotions about this history. Parts of me are numb. Mammy caricatures are cartoonish, ridiculous, and somewhat easy to access via eBay or vintage stores. Bullets and harm appear inescapable. I know what to expect when I’m presented with one of these things. Perhaps the numbness is in their redundant nature. There is no invention in such caricatures. Is white supremacy not bored?

This exhibition has me considering space in alternative ways. The Barnes Foundation, since its inception, has prided itself on being an educational institution. What does it mean to preserve and question history accurately and safely? An easy answer would be simply to return the objects. Objects made from natural materials such as wood are sensitive and can attract mold and pests. That’s a big no-no. In the past, conservators used materials such as arsenic to treat works of this nature. Storage facilities and science have gotten better, but sometimes religious items are rendered unusable because the chemicals would harm the wearer.3

When I think of the uprooting of objects—and people—I am hurt. I am hurt by the forced displacement and the violence often applied to “integrate” them into a new society. The uprooting is a trigger point. Le Déracinement (The Uprooting) amplifies this hurt, thrusting us into an uncomfortable space . Now that we are here, what do we do? That’s a big question to not answer, but certainly is something to consider.

Stephanie E. Goodalle is an art advisor and editor who documents the experiences of the Black diaspora. She is the creator of DSCNNCTD, a podcast dedicated to exploring the practices of emerging and mid-career Black and POC artists across disciplines. Goodalle recently wrote an essay for Allana Clarke’s solo exhibition Allana Clarke: A Particular Fantasy. Her essays and interviews have been published in publications such as ART PAPERS, BOMB, BURNAWAY, and Kenturah Davis: Everything That Cannot Be Known. She is a contributing editor for BOMB. Goodalle received her BA from Spelman College in Atlanta, GA and a MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.

References

| ↑1 |

“Welancora Gallery presents Le Déracinement (The Uprooting), Welancorna Gallery, https://www.welancoragallery.com/usr/documents/exhibitions/press_release_url/25/revised-press-release-le-d-racinement-the-uprooting-.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 |

“African Art in the Barnes Foundation: The Triumph of L’Art Negre and the Harlem Renaissance by Christa Clarke,” The Barnes Foundation, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/press/press-releases/african-art-book |

| ↑3 |

Maya Pontone, “Harmful Pesticides in Museum Collections Complicate Repatriation Efforts,” Hyperallergic, https://hyperallergic.com/803145/harmful-pesticides-in-museum-collections-complicate-repatriation-efforts |