Suzanne Bocanegra: Valley

Suzanne Bocanegra, Valley, 2021, installation view [courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, Austin]

Share:

“If I am such a legend, then why am I so lonely?” Judy Garland once lamented. The Hollywood icon was cursed with success from a young age, exploited by studio executives and those closest to her. Stardom gave way to addiction: Almost two weeks after her 47th birthday, the actress—best known for playing Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939)—died of an overdose.

Artist Suzanne Bocanegra has captured a moment toward the end of that arc in Valley (2018), a large-scale video installation recalling Garland’s wardrobe test for the 1967 film Valley of the Dolls. Based on the best-selling novel by Jacqueline Susann, Valley of the Dolls was inspired, in part, by Garland’s own showbiz rise and fall, a parallel made all the more ironic when her drinking and erratic behavior resulted in an early dismissal from the film.

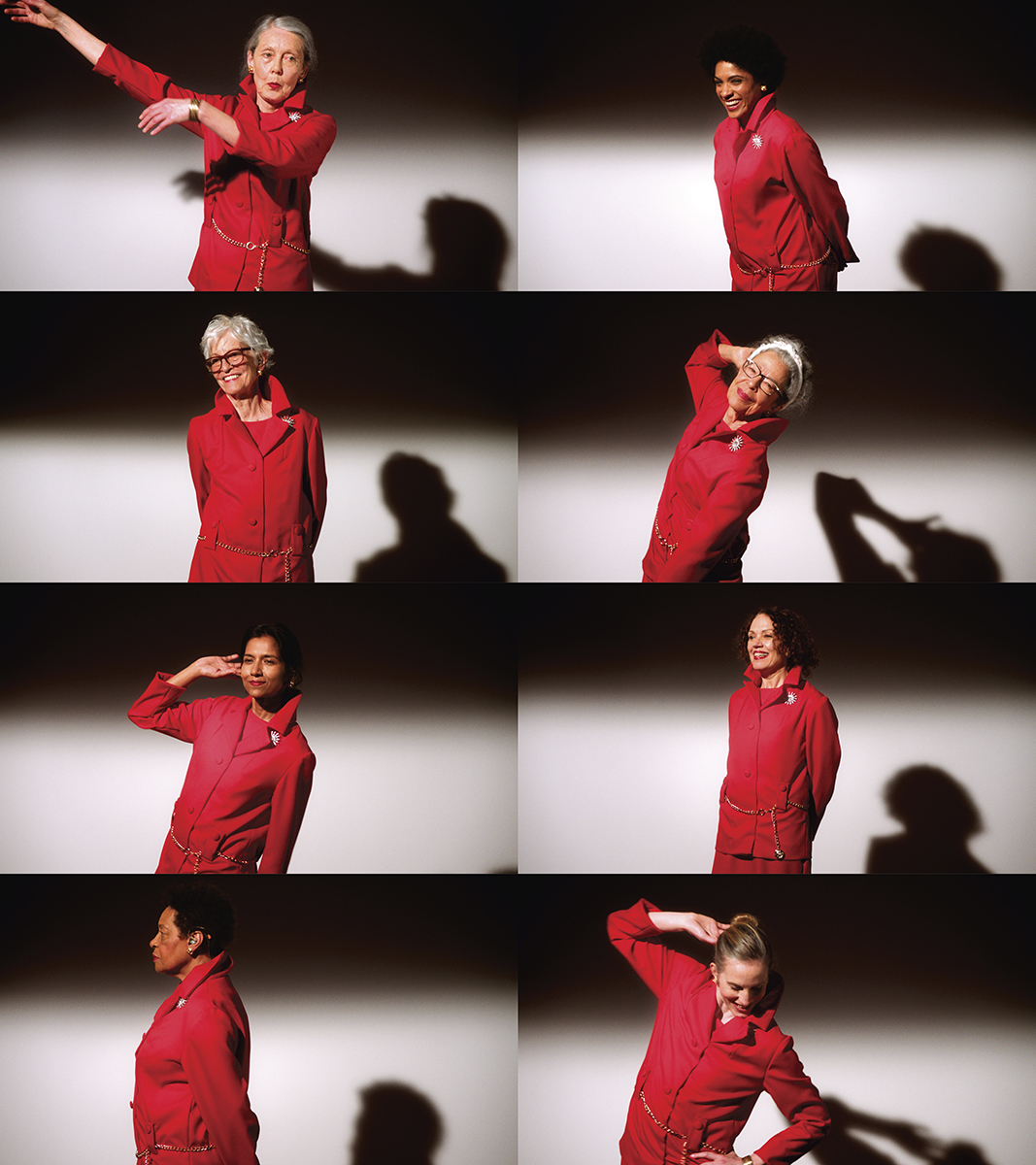

Valley is now on view at the Blanton Museum of Art at The University of Texas at Austin. It features eight noted female artists of various disciplines, each mimicking Garland’s on-screen movements and adding their own interpretive layer. The lineup comprises poet Anne Carson, choreographer Deborah Hay, performance artist Joan Jonas, vocalist Alicia Hall Moran, author and activist Tanya Selvaratnam, theater pioneer Kate Valk, contemporary artist Carrie Mae Weems, and prima ballerina Wendy Whelan.

Suzanne Bocanegra, Valley (stills detail), 2018, eight-channel HD video (color, sound), 4:44 minutes, in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum [photo: Carlos Avendaño; courtesy of the artist]

“The whole idea is to have this feeling of unison,” Bocanegra told me, the day before the opening, “even though they each approached it a little differently.”

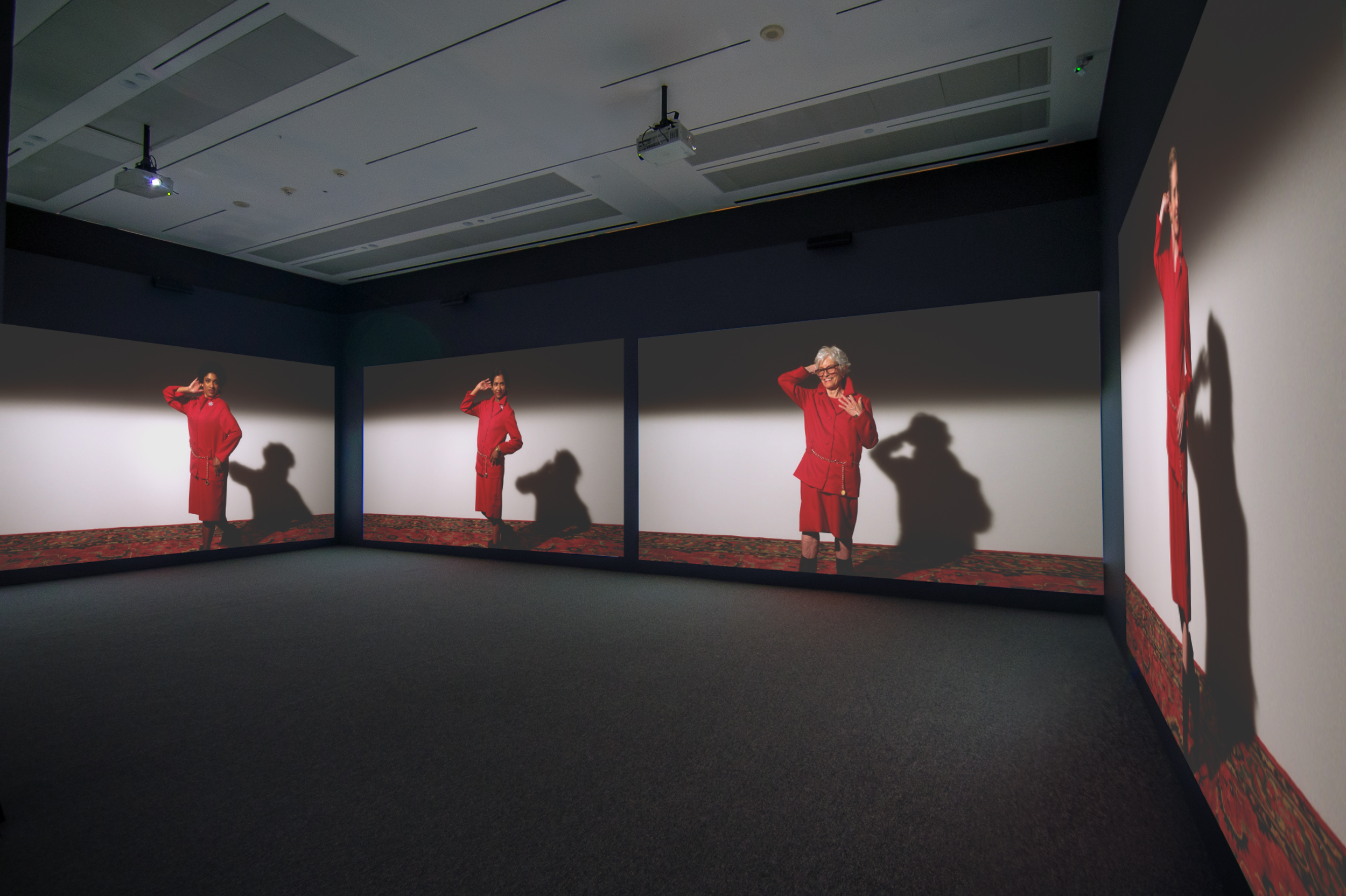

This is Valley’s third showing since its 2018 premiere at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. The long, narrow layout of that space accommodated eight colossal screens split over two opposing walls, carving out, in essence, a valley for the viewer to walk through. The Blanton’s square gallery creates an immersive Greek chorus effect, with two screens on each of the four walls. The performers, projected about 17 feet tall, twirl, pose, and chirp one-liners. Their voices and gestures, just slightly out of sync with the others, offer an echo chamber of Garland’s psyche.

In just under five minutes, the eight-channel composite reimagines all four shots from the original wardrobe test, using identical reproductions of the costumes produced by Fabric Workshop. Bocanegra told me she wanted to work with a range of artists she knew and admired, in order to explore different aspects of Garland: “Wendy Whelan has done this all her life as a dancer, she picked it up perfectly. Same with Deborah [Hay]. Kate Valk has done this at Wooster Group, so she also picked it up. Tanya [Selvaratnam] was trained by Kate. But the others had their own approach. Carrie [Mae Weems] is full of life; she has a big presence. And Joan [Jonas] doesn’t normally have a big smile, but she was copying Judy.”

The first shot involves a bright red ensemble, with each performer playfully obeying the voice off camera: Giggling, whistling, spinning when instructed. At one point, when asked to turn her back to the camera, the performer quips, “Without a cigarette and blindfold?”

The second shot features an orange silk kaftan, bold and marvelous, intended for a groovy grande dame. Yet the performers look uncomfortable as they do a doddery about-face, mumbling something about a “fiery, burning monk.” Facing the camera again, their expressions remain uneasy.

“It was a time in Judy’s life when nobody would hire her,” Bocanegra said. “She’s cracking jokes and saying things to be likable. She’s not quite acting, but she is performing.” Although we never see the original footage (you can go to YouTube for that), these eight artists eerily reveal Garland’s presence through her absence.

“Suzanne wanted to reclaim the power and womanhood of Judy,” Deborah Hay told me, explaining how each performer memorized the original wardrobe test prior to their own fitting. Bocanegra also instructed them through an earpiece, while movement coach Elizabeth DeMent (as well as Garland’s footage) mirrored from the other side of the camera. “Some of the gestures were quite self-conscious, like, ‘Why are you making me do this?’” Hay said. “[Garland] was being told what to do by the director, and it was belittling.”

Suzanne Bocanegra, Valley, 2021, installation view [courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, Austin]

Suzanne Bocanegra, Valley, 2021, installation view [courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, Austin]

That delineated self-consciousness becomes inescapable amid Valley‘s towering screens. The artists are at once poised and unsteady, sneaking downcast glances before looking up with tight smiles. It is impossible to experience all eight performances at once. The viewer must make split-second decisions about where to look next.

The last two shots in the sequence have no sound, as in the original tape. Wearing an outrageous, paisley-sequined suit, the performer takes a drag from her cigarette and looks momentarily self-assured. But her confidence is soon overtaken by a shakiness that makes her seem like a marionette, pulled by invisible strings. In the final moments, she dons a shimmering white evening gown and sways with arms gently outstretched. The silence amplifies a quality that is far less evident in the previous segments, of a little girl dressed as a grown-up, doing what she does so well: playing pretend.

Barbara Purcell is an arts and culture writer based in Austin, TX. Her work has appeared in Texas Monthly, The Brooklyn Rail, The Austin Chronicle, Canadian Art, Glasstire, and elsewhere. Her fiction has appeared in Tribes Magazine and Schuylkill Valley Journal. She is the author of Black Ice: Poems (Fly by Night Press, 2006) and has contributed to three anthologies. For more information, please visit www.barbarapurcell.com.