Eamon Ore-Giron: Competing with Lightning / Rivalizando con el relámpago

Eamon Ore-Giron, Cherry Truck, 2003, latex acrylic and gouache on canvas, 20 ½ x 21 ½ inches [photo: Charles White; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

Share:

Halves are made whole in Eamon Ore-Giron’s syncretic paintings, which combine elements from the Americas and Europe at different points in time into a single moment. In Competing with Lightning / Rivalizando con el relámpago, on view at The Contemporary Austin’s Jones Center in Austin, TX, three series span the last 20-plus years of Ore-Giron’s practice, beginning with early figurative works before heading into more recent abstract paintings. The survey, which originated in 2022 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver, is organized by MCA Denver’s Ellen Bruss Senior Curator Miranda Lash; its current iteration at The Contemporary Austin is organized by Assistant Curator Julie Le.

Ore-Giron, who turns 50 this year, conjures various settings in his paintings when examining the role of colonialism in North and South America, along with its legacy, including within his own family and identity. His bodies of work are stylistically distinct, even as they thematically connect. The Los Angeles–based artist and musician (he moonlights as a DJ) is a master mixer and remixer of ideas and influences with roots throughout contemporary culture and ancient lore. Born and raised in Tucson, AZ, to a Peruvian father and a mother of Irish descent, he has also lived and worked in his father’s native city, Huancayo, in the Central Andes, as well as in Mexico.

Tucson emerges early in the survey, with Ore-Giron’s use of house paint to create bright, flat landscapes, in what he calls a “desert noon” palette. The figures in these paintings are based on photographs—diners at a steakhouse, women in a kitchen. The subjects are often set against a demarcating horizon that both separates and connects the subject matter within each scene. Suburban Americans are placed on bright green golf courses, against a stiff blue sky, as are characters from Peruvian folklore; the background is a critique of Manifest Destiny, expressed Ore-Giron at the show’s preview in March, like a manicured lawn, where “the green represents that expansion of controlling the environment.”

Eamon Ore-Giron, Sueño Huamanguino, 2005, latex acrylic and gouache on canvas, 48 x 60 inches [photo: Charles White; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

The painting Sueño Huamanguino (2005), which is based on a photo that the artist took in Huamanga, Peru, depicts a local dance called Chonguinada, set against that desert noon palette. Costumed revelers take on roles of Spanish conquistadors, Indigenous women, and Mestizos—people of “mixed” ancestry—to festively parody the country’s complex colonial history. In a dreamlike state (sueño, in Spanish, means dream), the Chonguinada dancers recontextualize Peru’s cultural mythology within the American Southwest. The overlay of Andean folk dancing, on a golf course in Arizona, seems as plausible as it is surreal, given Spain’s colonial history in both regions, and the artist’s personal connection to each place. Ore-Giron has included a bearded character in the painting—El Chuto—who is of both Spanish and Indigenous heritage, and who moves between worlds in a manner that perhaps speaks to the artist’s own lived experience.

By the 2010s, Ore-Giron was incorporating more abstract elements into his practice by drawing upon pre-Columbian traditions and European modernism. In the survey’s Talking Shit series—which he began in 2017, while living in Guadalajara, Mexico—ancient Mesoamerican and Andean deities are awakened as hard-edge, prismatic paintings. Their sleek serpentine forms and dynamic lines give the ancient blueprints a contemporary treatment, reclaiming the origins of abstraction as something broader than a 20th-century Western invention. In Sky Memory / Cruz del Sur / Southern Crux (2017), two near-symmetrical forces seesaw on a fulcrum that delicately halves and binds them, a sort of symbiosis that speaks to the cross-cultural and trans-temporal themes present throughout this show.

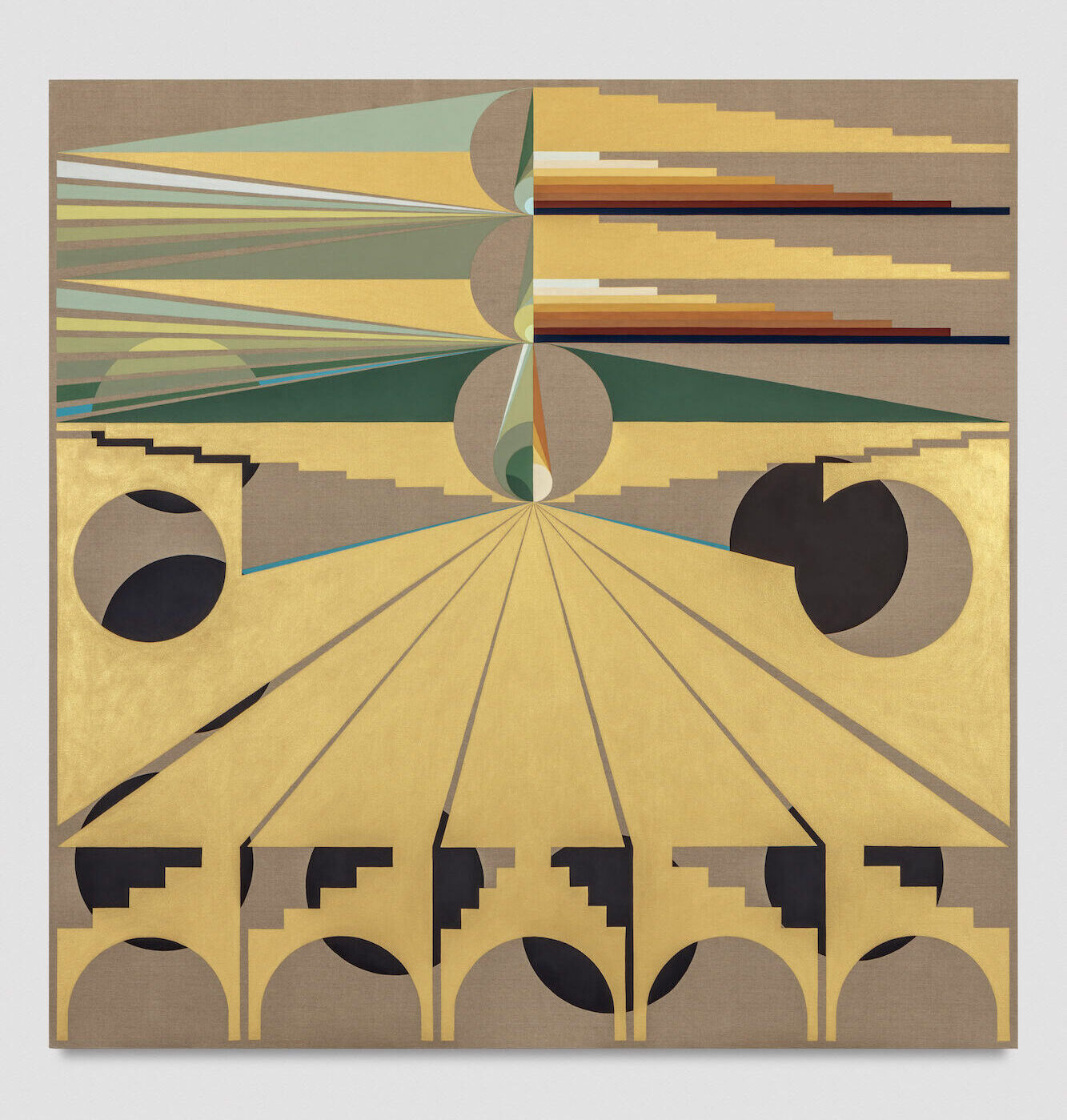

Eamon Ore-Giron, Infinite Regress CLXXXV, 2021, mineral paint and flashe on line, 120 x 120 inches [photo: Charles White; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

Eamon Ore-Giron, Infinite Regress CLXXXVII, 2021, mineral paint and flashe on line, 120 x 120 inches [photo: Charles White; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

The survey’s final—and best known—body of work consists of six grand-scale geometric abstract paintings from Ore-Giron’s ongoing Infinite Regress series, which he began in 2015. These vast window-like portals, all completed in 2021, are installed in their own contemplative space on the museum’s second floor, where they take on a visual surround-sound quality of potency and mystery. Planetary spheres (traced from vinyl records and old CDs) orbit around a sacred center point as gleaming gold paint dominates the beige linen canvas with the allure of art deco. Or El Dorado. Gold—both in meaning and material—held a powerful place among the Incas and Aztecs, before the Spanish conquered and plundered their empires. Through these various geometric forms (most notably, pierced spheres and dissected teardrops) Ore-Giron reinstates what was taken, as powerful rays project outward and inward ad infinitum.

The horizon line in each of these six paintings continues unbroken, like a circle, around the gallery’s perimeter. An infinite regress, in philosophy, refers to an endless sequence of preceding events with no beginning point: the origin of the universe, say, or the existence of God. Ore-Giron started this series not long after his mother’s passing and the birth of his son, which happened weeks apart. Standing before these cosmic highwayscapes, one gets caught up in the possibility of infinity—of unbroken circles and endless cycles; of moving between worlds in the blink of an eye. Competing with lightning, one painting at a time.

Eamon Ore-Giron, Talking Shit with Amaru, 2021, mineral paint and flashe on canvas, 132 x 204 inches [photo: Alex Boeschenstein; courtesy of the artist, James Cohan, New York, and The Contemporary Austin, Austin]

Barbara Purcell is an arts and culture writer based in Austin, TX.