2021 Texas Biennial: A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon

Sondra Perry, you out here look n like you don’t belong to nobody: heavy metal and reflective, installation view, 2019, video still [courtesy of Bridget Donahue and Ruby City]

Share:

Texas is as complicated as it is big, and the 2021 Texas Biennial, featuring more than 50 artists (mostly) working in and around the state, does not shy away from the state’s complexity. A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon spreads across four art institutions in San Antonio until January 2022; it also included programming at FotoFest in Houston, which ran until November 13. The dispersed presentation offers a broad assessment of Texas, from the political to the paradoxical, with particular attention paid to inequity, identity, and eco-calamity.

Organized by the Austin nonprofit Big Medium, the Texas Biennial is now in its seventh iteration, though not without some challenges. First, Covid prompted a yearlong postponement and logistical reconfiguration for social distancing measures. Then an increasingly divisive mood in the wake of 2020 spurred an expanded roster of artists, driven by aims of inclusivity. Basically, the biennial was going to need a bigger boat.

“We wanted to open up the Texas Biennial to other major cities in Texas, and it so happened that San Antonio’s institutions really showed up—which was wonderful, because San Antonio has a really dynamic, thriving arts community,” said Ryan N. Dennis, who co-curated the survey alongside Evan Garza. The geographic expansion led to a philosophical one, and the decision was made to include artists from Texas, for Texas, and/or outside of Texas. “Texpats” are represented, such as San Antonio–born artist and activist Donald Moffett, who has lived and worked in New York since the 1970s.

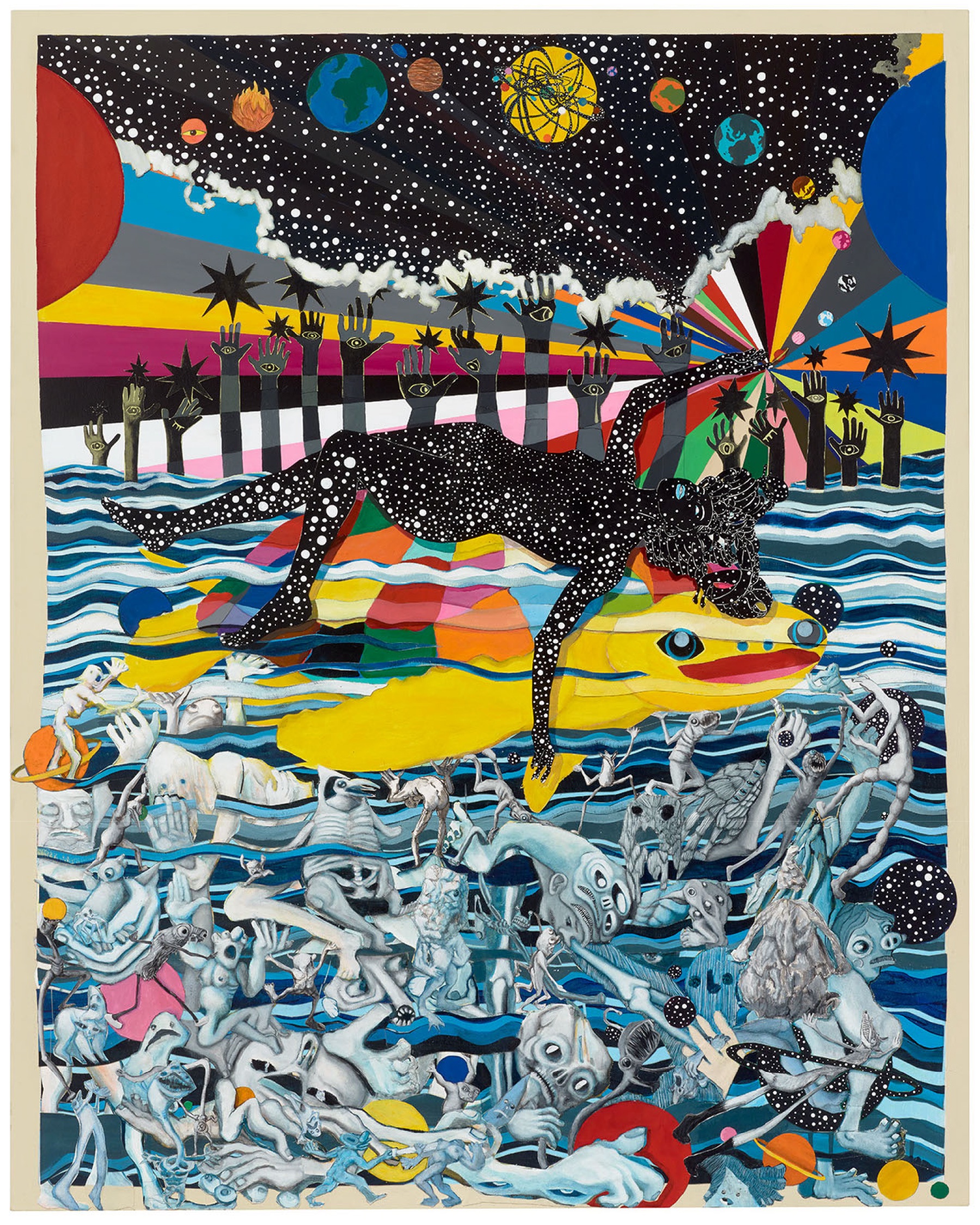

JooYoung Choi, Tourmaline the Celestial Architect, 2018, Acrylic and paper on canvas. [Image courtesy the artist and Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art, Houston.]

Dennis and Garza, both natives of Houston, are currently Texpats themselves. Dennis is chief curator and artistic director of the Center for Art & Public Exchange at the Mississippi Museum of Art; and Garza, a curator and writer, is a 2021–2022 Fulbright Scholar at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. “We understand Texas through a Houstonian lens—an incredibly diverse city, an immigrant city, and a sprawling city filled with endless points of entry,” explained Garza. “We wanted to build a biennial [with] many points of entry about who identifies as Texan and why.”

Those who identify as Texans reveal an impressive diaspora within the statewide survey. It includes Irish artist John Gerrard, whose digital photographic installation recreates a 1930s dust storm in the state’s panhandle; Korean American multimedia artist JooYoung Choi; New Jersey interdisciplinary artist Sondra Perry, who spent part of her childhood in North Texas; and Houston native Melvin Edwards, who in 1970 became the first African American sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “We wanted people to see that Texas is this huge place that literally has reverberations in and out of the state,” explained Dennis. Perry and Edwards are both featured at the biennial’s Ruby City venue, alongside four other artists who are known to repurpose found objects and discarded materials in their practice.

Perry’s you out here look n like you don’t belong to nobody: heavy metal and reflective (2019) is a literal crucible for forging new narratives from past relics. Railroad spikes, shackles, even meteorites, represent histories alchemized through technology (HD video in this case) as a way to reclaim Black identity. Similarly, Edwards, now 84, uses a kind of restitutional blacksmithing in his works of welded steel. Two small reliefs, New Cult (2007) and Nite Work (2012), examine the weight of racial brutality through chains, tools, and other metal objects. From afar they appear eerily understated.

Sondra Perry, you out here look n like you don’t belong to nobody: heavy metal and reflective, installation view, 2019, video still [courtesy of Bridget Donahue and Ruby City]

At Artpace, Kaneem Smith’s Migrant Barrier Tapestry (2018) stretches across the front window display, a colossal critique of global commodity chains. Smith’s giant flag of burlap sacks and bright colors gestures toward the Latin American coffee market, pointing to the Indigenous regions where beans are grown, and to the transnational corporations in charge of their import and export. Smith’s tapestry represents the inextricable relationship—though separated by clear seams—of worker, owner, and consumer.

The lion’s share of the biennial is at the McNay Museum of Art, which includes the Houston-based Filipinx collective FxAH. A salon-style wall in the Lawson Print Gallery pieces together more than a dozen of the collective’s prints and paintings—mostly portraits—like an eclectic puzzle. Adjacent to this wall is Matt Manalo’s Evolution of the Filipino (2018), a six-phase painting completed on sewn-together white rice sacks to depict Kenkoy, a cartoon character made popular in the Philippines around 1929. The painting includes a sequence of heads, starting with a stark black silhouette, that evolve into the character’s facial features before fading into whiteness. This gradual dissolution from image to emptiness, not unlike the lunar cycle, is a waxing and waning of identity, invisibility, and assimilation.

A video installation by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello in the McNay’s Frost Galleryflashes hot pink beams across the screen. Teeter Totter Wall (2019) documents a project at the US-Mexico border in which brightly colored seesaws were inserted through the imposing steel bollard fencing. Drone footage shows individuals on both sides of the wall enjoying the limited contact those playful seesaws afford.

In the atrium of the Frost Gallery, Steve Parker’s Sirens (2018) is an imbroglio of brass horns blaring various voice recordings in a collective call to prayer. Inspired by the civil defense sirens used in World War II, Parker’s sonic sculpture beckons the listener to come closer, though the sirens’ allure rests in mystery rather than in urgency.

Steve Parker,Sirens, 2018,Brass, plastic, conduit, speakers,and recorded voices[photo: Image courtesy the artist San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio]

Irene Antonia Diane Reece’s multipart installation Home-goings (2019–ongoing) transforms the back area of the Frost Gallery into a chapel of memory and metaphor. Pulling from her own family’s archive, Reece—who considers herself a “visual activist”—pays homage to the African American community in Houston from which she hails. Bright artificial flowers shower the floor before a prayer kneeler, adjacent to an altar of sorts: an enlarged black-and-white photograph taken years ago at Reece’s father’s church in Conroe, TX. The image, printed on two large sheets that nearly connect in the center, invites the viewer to come closer and reflect upon the history and legacy it represents.

At the San Antonio Museum of Art, an elegant dragon-like installation greets visitors in the main lobby. Made of 8,807 paper plates and a closetful of colorful saris, Abhidnya Ghuge’s When He Believed She Could Never (2021) is a composite sketch of womanhood. Each sari woven carefully into the sculpture’s wire armature was owned by an individual who has included her personal story to accompany the site-specific installation—intended to evoke an“abstracted cervical spine,” according to Ghuge—that climbs toward the ceiling to reach new heights.

Abhidnya Ghuge, sculpture, “When He Believed She Could Never”, installation view, 2021 [photo: courtesy of the artist and San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio]

Upstairs at SAMA, a conversation takes place on the walls of a single room, including works by Virginia Jaramillo, Tomashi Jackson, Vincent Valdez, and Trenton Doyle Hancock. Valdez’s series of graphite etchings, titled Somewhere in South Texas (2015–2020), documents various scenes, real and imagined, along the border. Hancock’s take on Texas comes in the form of a state-shaped fuzzy black vortex titled Step and Screw: Meanwhile, Somewhere in Texas (Five Foot Furry Flash) (2021).

José Villalobos’ installation stuns as the room’s centerpiece, a rhinestone-crusted saddle suspended in space above a sprawl of dirt. Los Pies Que Te Cargaron (2020) includes a pulley system of ropes connected to plaster hands that reach for plastic sprigs of flowers, just beyond their grasp. A pair of cast feet grounds the artist’s absence. The Feet That Carried You, as the title translates into English, seeks to reconcile entrenched cultural expectations by turning traditionally masculine tropes (namely cowboy culture and Latin machismo) into something flamboyantly defiant.

Jose Villalobos, Los Pies Que Te Cargaron, Installation view, 2020,[photo: Jose Villalobos; courtesy of the artist and Mexic-Arte Museum, San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio]

FotoFest in Houston continued this broad conversation earlier in the fall with In Place of an Index at Silver Street Studios. Associate Curator Max Fields collaborated with Dennis and Garza to present a photography-centered exhibition speaking to what Garza calls the malleability of the past: “That’s an overarching theme in the biennial: how we tailor history to our own needs, which is a pressing concern in contemporary American society.”

The biennial’s title, which appears to reference the pandemic and ongoing issues of political and social unrest in this country, actually draws upon a quote from the artist Felix González-Torres in relation to Roni Horn’s iconic sculpture Gold Field (1980–1982), which González-Torres first saw at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1990. The sculpture—a feather-light sheet of unalloyed gold resting on the gallery floor—represented hope in its purest form for the artist: a new landscape, a possible horizon, a place of rest and absolute beauty . . . a place to dream, to regain energy, to dare.

Barbara Purcell is an arts and culture writer based in Austin, TX. Her work has appeared in Texas Monthly, Salmagundi, The Brooklyn Rail, and The Austin Chronicle, among other publications.