Porous Cosmopolis: Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman

“UCSD Community Stations” [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

Share:

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s many co-extensive projects merge activist praxis, intellectual and skill exchange, horizontalist planning, and creative production to examine and change the way that borders, and the communities around them, are conceived of and function. These initiatives tend to work in a state of constant engagement and opportunism, redirecting academic, government, and private funds toward community stakeholders to sustain communities on both sides of border regions, particularly the fraught imaginary line between San Diego and Tijuana—among the largest binational metropolitan regions in the world. Cruz and Forman combine their backgrounds in architecture, planning, visual arts, and social sciences to facilitate the creation of sustainable community-led social organisms. Alongside their on-the-ground work, they are engaged in several conceptual and political projects to rethink the policies and projects that govern different border regions, which is also the subject of their forthcoming book, The Political Equator. I spoke with them about their recent activities and ever-developing conceptions of border penetration and bottom-up planning.

Rachael Rakes: Tell me about what you are doing right now. You told me you were just finishing a workshop in Chicago related to your participation in the recent Venice Architecture Biennale—the border estuary project that you showed there?

Fonna Forman: Yes, The University of Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago co-curated the US Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, and this workshop was a follow-up to that.

Teddy Cruz: One interesting thing about this workshop was that most of the people participating were coming from social and political sciences, with a bit of urban theory, instead of from the arts or architecture. A lot of them were interested in the role of cultural producers, of art, architecture, and urban practice to rethink particular protocols often embedded in more econometric fields, such as social science—and the way they measure reality.

For us, it was very similar to the situation we have found ourselves in at [University of California San Diego], because I teach in the visual arts, and the visual arts increasingly has been interested in coordinating pedagogical frameworks in a more integrative agenda, let’s say, towards the city and the territory. But also, university-wide, we don’t have a school of architecture, and so the center, the Center on Global Justice, and UCSD Community Stations, the Cross-Border Initiative that Fonna and I have advanced, becomes a bit of an alternative platform for many of those researchers and students who are seeking to make those connections.

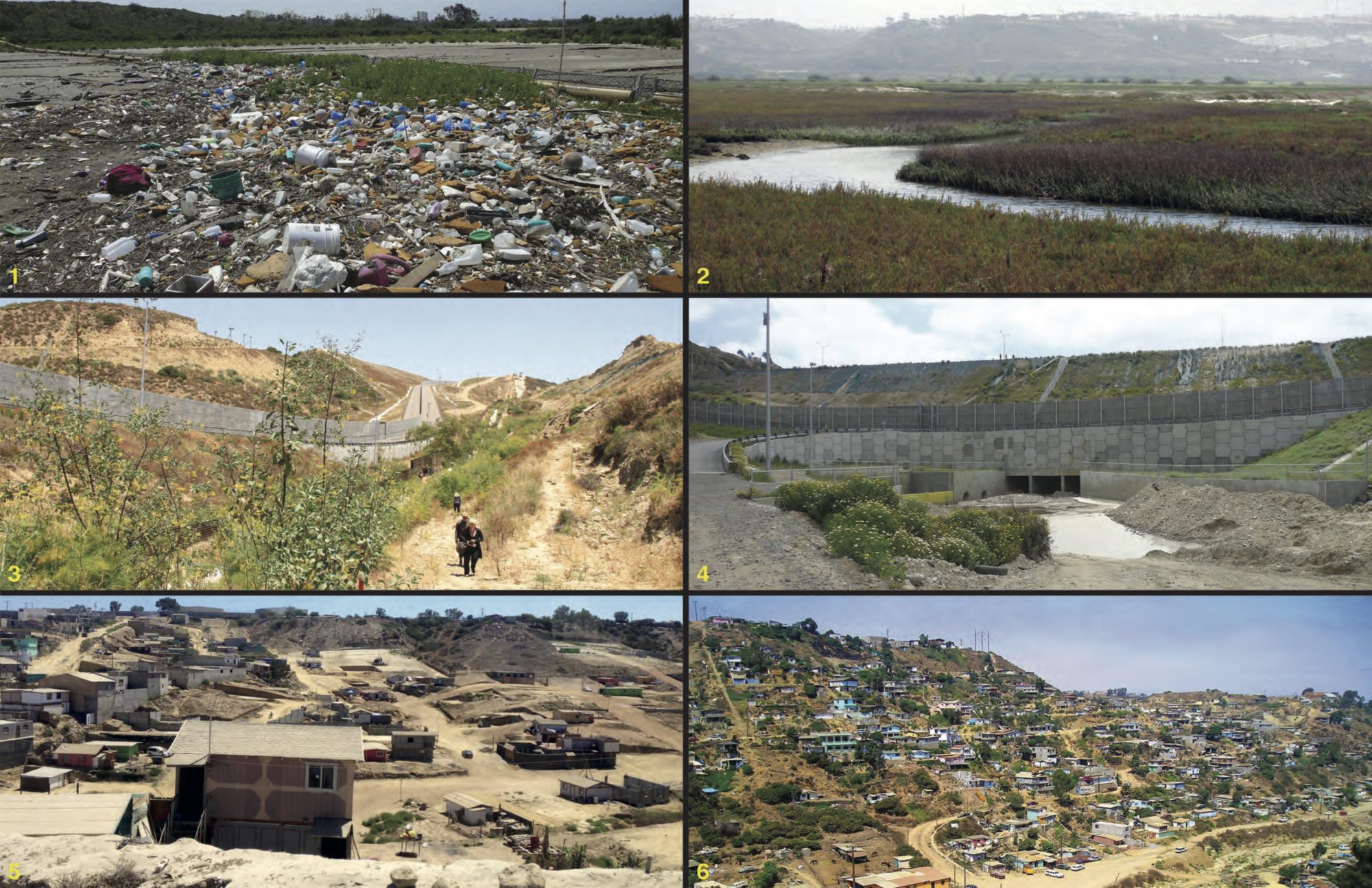

Cross-Border Environmental Commons [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

RR: Do you work with artists as well within the Cross-Border Initiative?

FF: Increasingly the artistic and cultural dimension of our interventions has really taken precedence. We work with students and faculty, across the campus, from a variety of disciplines: from engineering, to the natural and physical sciences, to medicine, and social sciences. But we’ve come to understand that the way to build trust, and to open new horizons of thinking in the communities where we work, is to engage through arts and culture.

TC: One of our major projects is these UCSD Community Stations, which are field stations located primarily in immigrant, low-income neighborhoods where teachers and researchers work collaboratively with community partners and grass-roots organizations. There we have been designing a sort of alternative curriculum from within the university. This is the more subversive part of it, because we have gotten funding that enables us to bring activists to co-teach with us—people who do not have credentials to officially teach in the university, but whose social, economic, and political knowledge could enable the reorganization of research agendas from within the university.

FF: We’re operating from the base of a big public research university that typically doesn’t see its relationship with communities as a collaborative one. It’s typically seen as a humanitarian gesture, [wherein] the university, with its goodies, its resources, its knowledge, improves the world and plants a white flag and says, “Look what we’ve done.” We’ve been interested in changing that understanding of university-community partnership, tipping the relation from a vertical to a horizontal plane. For us this is a more ethical, a more responsive and ultimately a more sustainable way of thinking about connecting top-down and bottom-up knowledges and resources

UCSD Community Stations [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

RR: Could you illustrate a result of that combined knowledge or a partnership that’s being built right now?

TC: One would be the Community Stations, because of the alliance that we created between our university and the grass-roots organization. The San Diego Unified School District gave us access to a four-acre piece of public land that has been vacant, largely because that parcel is surrounded by six public schools. We proposed to them to create a new form of experiential environmental outdoor learning, that can also enable after-school programs. What makes it unique is the connection of the indoor classroom learning with outdoor, experiential, environmental education. With our partner (Groundwork San Diego-Chollas Creek, which is an environmental justice agency) we’ve been designing collaboration with teachers, community workshops and so on. What eventually became evident is [that] the programmatic and economic power of the major university in this case could also be leveraged for the grass-roots organization to develop the public space.

FF: We have another project, Living Rooms at the Border project in San Ysidro, which is a mixed-use affordable housing development. Here, the university worked with the nonprofit organization Casa Familiar to identify funding streams that wouldn’t have been available if we were not working together. We have discovered that the university’s social capital, networks and programmatic capacity can become leverage for communities developing their own work. We were able to tap into philanthropy in New York City and, together, get an ArtPlace America grant, to advance this as well as working with the city of San Diego to secure new market tax credits for the project. So there’s a sharing of ideas, a sharing of networks, together producing new streams that enable community-based development.

TC: And Rachael, this is so complex and maybe it’s difficult to get to the detail, but a major gesture emerging from these crazy, masochistic processes is that we are really prioritizing and coming up with new forms of economic and community development—that communities can be and should be in charge of their own resources, that not only affordable housing developers but also more benign progressive developers really should be tasked with producing these projects. Often they take advantage of nonprofit organizations symbolically just to requalify for tax credit subsidies and so on.

The Cross-Border Environmental Commons [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

TC (cont.): This may be an example of what we mean by collaborative education: That a lot of our effort has been to produce a new form of pedagogy, and thinking that art can be a cognitive tool to access the complexity of organizational issues. What is density, what is mixed-use, in what ways should a community demand more just forms of development from rental conditions to enable small-scale housing projects? Anyway, so the major effort in this project is how to increase or question a community’s capacity for political action. And that becomes an issue of visualization.

FF: One of the challenges in this city, as in many other cities for sure, is that many of these communities are preyed upon by developers and economic development agendas that see these neighborhoods as ripe opportunities for profit. The community planning groups are typically comprised of people who have good reason for being worried about particular kinds of investments in their neighborhoods. [Often] these communities are sold a bill of goods, that “If you only would whitewash your main street and put on façades” the whole new urbanist agenda, “your property values would go up, and it would bring more investment into to the neighborhood” and so forth. To a lot of people that sounds great—they want their neighborhoods to be pretty, but we want to help residents understand that there are other alternatives, that they can actually steward their own development and not surrender to the developers’ agendas.

TC: We’re interested in challenging advocacy planning that just comes down to developers in alliance with planning agencies that come up to neighborhoods like the ones [where] we work to really seduce the community into how they’re going to beautify [it], but also only to talk about identity as a way of packaging style, or identity through style. …. Many of these workshops in the beginning of our journey had to do with re-orienting the conversation beyond style and more on the everyday practices of residents in the community who negotiate boundaries, spaces, economy, more social and economic registers. That requires an interesting process of translation. We often see it as a curatorial and translational practice that creates interest in how this bottom-up sensibility can really produce a new form of political imagination.

The Cross-Border Environmental Commons [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

RR: If we compare this to other interdisciplinary or social art practices, how much of a reliance is there still on you two as individuals to maintain this? Is there an end goal to make this function without you, or that can be adapted for other places? Do you have a plan to slowly walk away?

FF: We are constantly in a mode of seeking resources and funding to enable us to have staff, talented people working with us in our office to help us lead many of these things. Again, because we’re not connected to an architecture school here at the university, every architect, every designer we bring in has to come in from the outside, and we need to find grant funding and philanthropic support to fund those people. Usually these people are young, and they come to our office to learn, and while they’re very creative and so forth, obviously they’re not at the sort of level where they can lead projects of this complexity. We find ourselves playing many roles, from the nitty gritty work on the ground all the way up to high-level management [conversation] with the campus on sustainability over time. It is overwhelming sometimes.

TC: And that’s one reason we believe in the relationship of protocol and physical systems, designing governance, forms of governance, and really the kind of programmatic complexity that can sustain itself through time, but also the physical systems to support it. To summarize, [we lead] three community stations: one is a four-acre open-air climate action park connected to six public schools through participatory environmental climate education. Another one is [San Ysidro, which] broke ground two weeks ago after years of struggle, because these projects begin with nothing, really. We had to assemble many different things. The point is that this second community station is 10 units of affordable housing that surrounds the community station itself. The community station there takes the shape of a black box theater with a recording and sound studio and an open-air classroom for arts and culture activities––so we have designed the programmatic compendium very carefully to fund those programs, and our community partners have opened up their own. A nonprofit has opened up its own structure to accommodate those programs in perpetuity, we hope. So even if we were to unplug, we already have set up (we hope) the special intelligence of these relations: housing that is connected to a public space that performs in very specific ways. We’ve been arguing that houses in this neighborhood cannot exist on their own, [that] they have to be in units. Housing needs to be embedded in an infrastructural support system.

UCSD Community Stations [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

TC (cont.): Finally the one in Tijuana is an informal settlement of 85,000 people that crashes against the border wall, and there we have secured, through our negotiations with the Tijuana municipality, seven small sites across the informal settlement, including the site where we are building the station itself as an environment to produce similar efforts with our nonprofit. It’s not only an issue of designing things or objects, it’s about designing processes—civic, political, economic—that can secure the construction of that platform for it to perform.

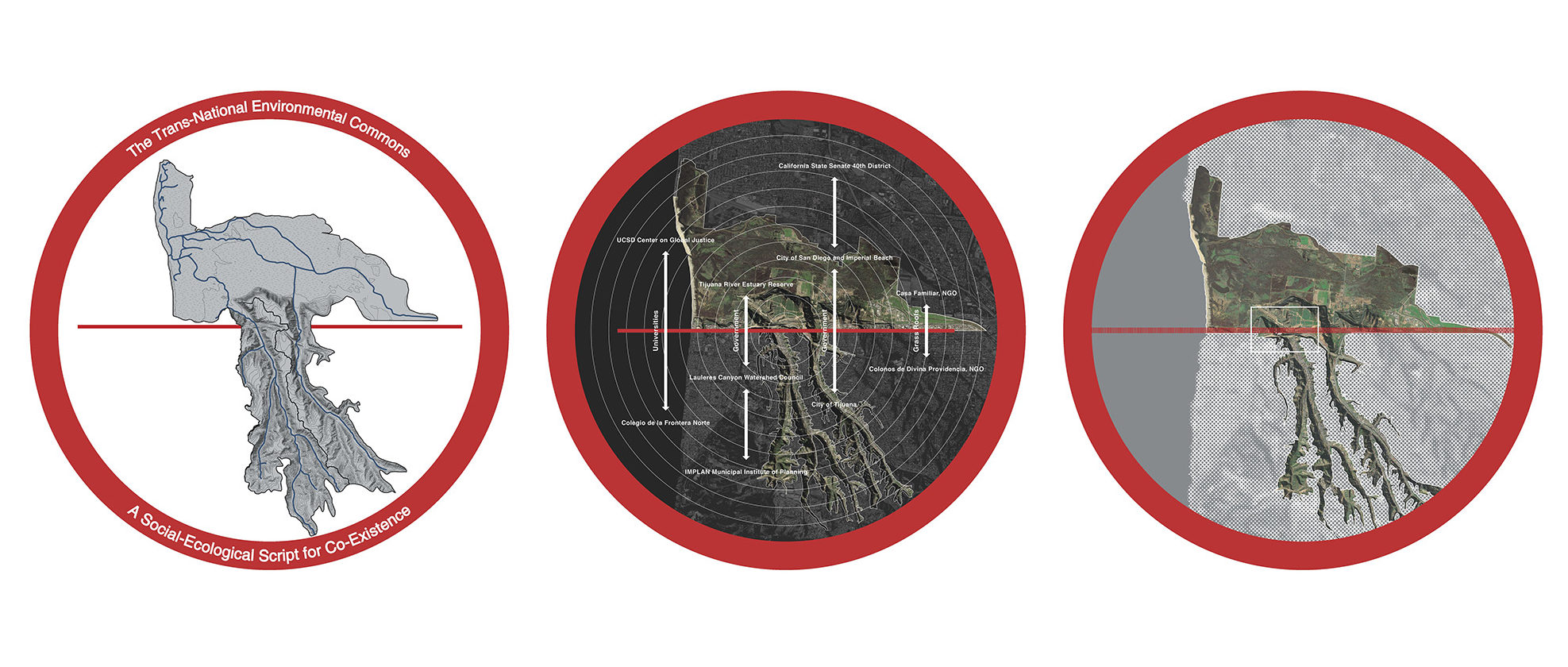

FF: What is key is cultivating a network of institutions to support them and feel invested in them. Thinking about these interventions temporally—long-term versus short term—might be a good way of transitioning into some thoughts about the border. The border then becomes less a line, a thing, or an object and more like tissue of spatial and social ecologies. The tissue is a representation of what both sides share, and both sides have an interest in protecting in the future. It’s been a very productive visual tool, to rethink the border less as a line, a stupid 19th-century rationalist gesture imposed on territory, and instead as an opening to rethinking it as a zone, as a region, containing many shared assets. That’s ultimately what the MEXUS project was about.

RR: Yes, let’s talk a bit about that project.

TC: The need to understand the specificity of political and economic and social dynamics in zones of conflict has been the framework of our efforts. We have to begin with the recognition that the destinies of San Diego and Tijuana are intertwined. This is something that, while part of our conversation locally through decades, is never really understood, primarily in these moments [when] the kind of xenophobic politics of division and polarization come back to define the terms. Ultimately [what] emerges from MEXUS are its assets, its potentialities, the shared interests and values in divided geographies. The visual cognition of those assets would be the prerequisite for a new political will, of shaping interdependence, of a new cross-border citizenship.

MEXUS: Collisions between the political and the natural [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

TC (cont.): We need to be aware of what shapes a territory because otherwise the wall just becomes a cheap message of security. The project that emerged that is more specifically political, which is part of our ambition right now, is that our community station located in this informal settlement of 85,000 people is a canyon directly [corresponding] with an environmentally protected zone on the US side in San Diego. It’s an estuary called the Tijuana River Estuary. Obviously these two environments are next to each other and separated by a military zone, so there is this incredible specificity of militarization and environmentalism in close proximity, and this is part of what interests us. But the project that emerged from MEXUS is that we have been assembling a cross-border coalition of institutions.

The mayor’s office of Imperial Beach (which is a city right next to the wall at that point), the city of San Diego working with a state senator from California, sharing the environmental committee, UCSD, grass-roots organizations on the San Diego side, in Tijuana grass-roots organizations, universities, and nonprofits, all form what we are calling the cross-border environmental commons. It’s a political and social and ecological envelope that connects the informal settlement with the estuary, bundles them together across the border as series of still-available lands in the informal settlement, lands that haven’t been claimed yet by squatters. It’s bundling this archipelago of conservation in the informal settlement with the idea that, by protecting those chunks of land and injecting into them protocols for conservancy and community programming, we can then protect the estuary on the US side, because the estuary we are elevating is not San Diego property but a binational biregional environmental asset that needs to be taken care of collaboratively.

The reason I’m saying this is because in the last years, since the border wall has been increasing and hardening in its presence, ironically it has accelerated a flow of waste from the informal settlement into the estuary. What we’ve been claiming is that in investing collaboratively in this informal settlement, through education, physical, and water/waste management infrastructure, we are sending the message that the poor, informal settlement can be, in fact, the protector of the estuary.

MEXUS: Collisions between the political and the natural [courtesy of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman]

FF: So this is a very local political project. Zooming out a little bit, one of the things that MEXUS does is [demonstrate] all of the points along the trajectory of the continental border, where you see these kinds of political, jurisdictional, and natural conflicts.

After all, MEXUS really is a very strange, amorphous kind of regional zone defined by watersheds. The shape of MEXUS is the shape of the eight main binational watershed systems that are shared between the US and Mexico. Obviously ours is one of those.

TC: The specter of a new border wall is that it would further dissect those systems. If you begin with the political equator (it is in that diagram we propose at some point), these global border threads—the most contested checkpoints in the world—are emblematic of almost any imaginable conflict distributed across the world atlas. In this essence, I think the provocation for our practices is that conversations about globalization or global planning or the rethinking of global institutions—[that] these conversations cannot occur without considering the conflicts between geopolitical borders, national systems, and marginalized communities/poverty. I think that triad is [a] fundamental framework for any research practice today. These things cannot be disentangled.