Pearl Cleage: Fragile Bodies on a Fragile Planet

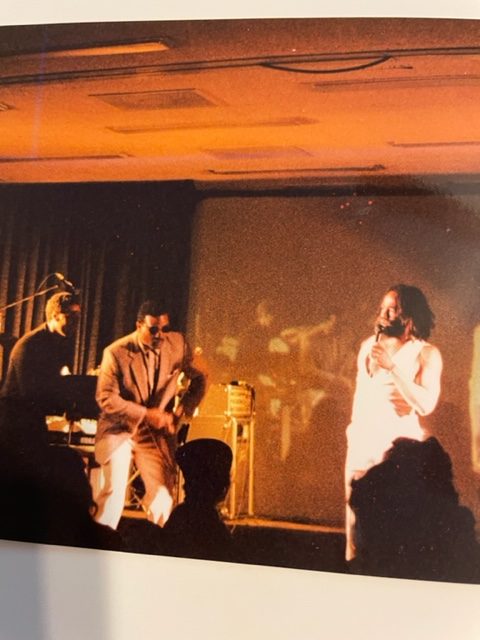

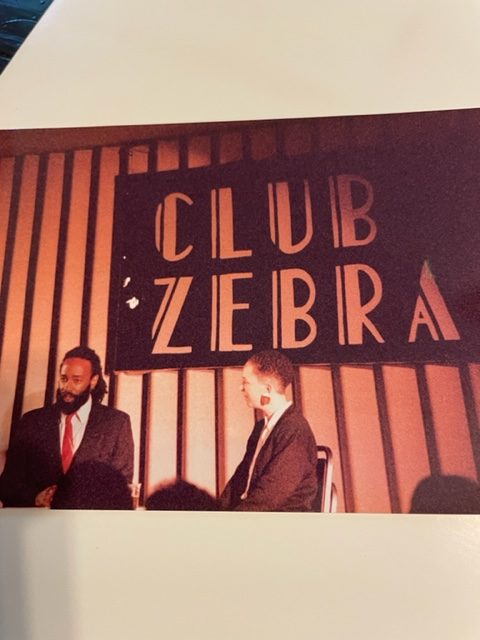

Club Zebra, ca. 1990, vintage photograph [photo: Sue Ross; courtesy of Pearl Cleage and Zaron W. Burnett, Jr.]

Share:

Playwright Pearl Cleage received an enviable welcome to the ranks of novelists when Oprah Winfrey chose the Atlanta-based author’s first book-length work of long fiction, What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day (1997), for Oprah’s Book Club. Since then, many of her novels—set in and around Cleage’s own southwest Atlanta neighborhood—have become best-sellers, including 2005’s Babylon Sisters. Cleage makes a splash in whatever pond she enters: Her 1992 play Flyin’ West became “the most produced new play in the [United States] in 1994,” according to her website. Among her honors are an NAACP Image Award for her 2006 novel, Baby Brother’s Blues. Cleage’s most recent book is Things I Should Have Told My Daughter: Lies, Lessons & Love Affairs (2014).

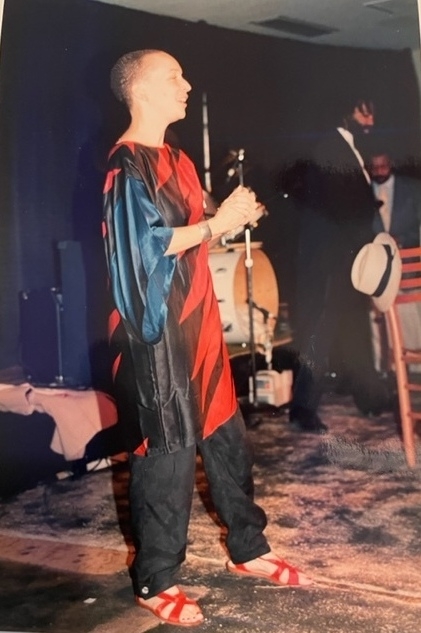

Pearl Cleage at Club Zebra, ca. 1990, vintage photograph [photo: Sue Ross; courtesy of Pearl Cleage and Zaron W. Burnett, Jr.]

Edward Austin Hall: Pearl, your sharp, eye-opening essay “Mad at Miles” has found a new audience 30-plus years after its chapbook publication, thanks to New Yorker critic (and former Atlantan) Emily Nussbaum’s essay “Confessions of a Human Shield,” which also addresses what to do with art by awful men. How do you feel about that issue nowadays—and about the movements around it?

Pearl Cleage: “Mad at Miles” grew out of a specific time in my feminist awakening. A friend had given me [the Miles Davis album] Kind of Blue, and I loved it so much. When I read Miles’ autobiography ([written] with Quincy Troupe), I felt personally betrayed by his casual violence toward—and disrespect of—women. It made me want to do something dramatic to express that feeling of confusion and rage. It’s hard to understand how the same human can write such beautiful music and also do such violent things. I almost felt like I should have known, like there should have been something in the art that let me see the imperfections in the man that Miles was.

But thinking about that led me to consider all the violent men who had produced art that was pronounced great, usually by other men, and how I was supposed to think about it. I remember raising the question with my friend, jazz critic A.B. Spellman, who had given me Kind of Blue in the first place. And he said, “Well, Pearl, if you’re going to discard all the art made by bad men, there are going to be a lot of empty library shelves and museum walls.” And I said, “Well, that’s what needs to happen, then.”

Of course, that’s not what happened, but my pursuit of a way to think about the problem was a critical part of my own consciousness-raising. I am very clear these days about not spending time with work made by woman-haters. I am pleased that “Mad at Miles,” the essay and the book, have been helpful to several generations of people trying to come to terms with what sexism and woman-hating look like in our everyday lives and how they impact our cultural lives, as artists and audience. It is a source of real pleasure to me that this work continues to resonate for people.

EAH: You dedicate your collection Flyin’ West and Other Plays [1999] to Zeke—your husband, Zaron Burnett Jr.—“from whom [you] continue to steal [your] best lines.” In our age of ubiquitous digital sampling, could you discuss your influences and borrowings, as well as the ways you make things your own?

PC: That question made me smile. I am a creative borrower, but Zeke is the only person I actually steal whole lines from! It’s his own fault for speaking in ways I can’t improve upon. But I don’t sample other people’s work. I understand how that works in music, but I don’t know how that could happen in written work. I have lots of influences. Toni Cade Bambara was a big influence on me. Her easy way with the creation of characters that ring so true was inspirational. Her short story collection Gorilla, My Love [1972] remains a book I return to for lessons on how to write about Black folks with complete honesty and absolute love—not always an easy thing to do! Alice Walker is a great influence. Her honesty and complete willingness to trust her own creative and political curiosity always push me to question what I already know in the hope that I will have the courage to push through to what I don’t know.

I grew up with my mother reading Langston Hughes to me at bedtime, and then giving me his books, so he is a big influence, too. He made me understand that you can embrace the whole world from the specificity of your American Negro-ness. The first scene of The Big Sea [1940] where he goes to sea, and as the ship pulls away from Sandy Hook, he throws all his books overboard so he can clear his head and start his life as a grown man— The idea of throwing books in the water was so forbidden and so exciting [that] I still carry that image with me. I feel that way at the start of every project: Throw out what you know, everything you’ve got, and start again. When Zeke surprised me by driving me to Sandy Hook a few years ago, it was like I was visiting a personal shrine.

Which brings me to Zeke as a huge influence on my work. Living with someone who is not only a wonderful writer but a fearless human being who has lived so many lives as a free person is a daily challenge to any tendency to lean into anything less than the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. He is always my first audience and my best one. So, those are influences, but I think I am equally influenced by just watching people. Listening to what they say. Watching them confront the complex challenges of just living every day. I am endlessly fascinated by people. I am one of the few people who can stand in line at the post office without frustration as long as there are a few big talkers in the line with me.

The thing that strikes me more and more as I get older is how we spend so much time and energy and bluster building cities, having wars, dominating and insulting each other, when all the time, we are living inside these fragile bodies that have to exist on a fragile planet in the company of other fragile beings and unknown viruses. We act like we are alone in the universe, free to follow our giant, violence-prone brains wherever they lead us. Not all of us are this way, but the ones who are [this way] continue to rattle their sabers and drop their bombs and poison our water, and what do we / can we do? I think about this a lot.

EAH: For people not lucky enough to ever have attended you and Zeke’s late-80s/early-90s Club Zebra, Atlanta’s only floating speakeasy and cabaret and the international center of bohemian Negritude, could you describe it and its evolution, and perhaps illuminate which more widely known works of yours might have stemmed from those performances?

PC: Club Zebra was a performance installation that came from a conversation Zeke and I were having when we unexpectedly inherited the leadership of Just Us Theater Company and were in the midst of planning a season. Zeke is not a fan of proscenium theater, and he was adamant that we would not be doing conventional plays in a conventional format. I was ready for something new, and I asked him, if he didn’t like proscenium stages, what did he like, and he said, “I like clubs.”

“So make us a club,” I said. And he created Club Zebra, “Atlanta’s only floating speakeasy and cabaret and the international center of bohemian Negritude.” In one of Zeke’s many lives prior to his landing in Atlanta, he had managed a real speakeasy, and frequented many others, so he knew what it took to make a good one. “A lot of times people are uncomfortable in the theater,” he said, which I knew was correct. “They are not sure how to act, but everybody knows how to act in a club/speakeasy. So, let’s make them comfortable, and then we can say whatever we want.” How could I resist?

Club Zebra, ca. 1990, vintage photograph [photo: Sue Ross; courtesy of Pearl Cleage and Zaron W. Burnett, Jr.]

We recruited the Spelman College Jazz Ensemble, under the leadership of Joe Jennings, to be our house band, since we both thought our audiences would enjoy the experience of seeing a group of young black women who could actually play and sing jazz. Their appearance at Club Zebra was their first time appearing off campus, and the reception was so strong [that] they began an annual fundraising tour, which continued for many years.

Zeke and I wrote and performed solo pieces meant for the intimate space that Club Zebra was. It was so exciting to be that close to the audience and to be performing my own work. I had not done a lot of performance work at that time, although I had done a lot of poetry readings. But this was something else! This was theater! And it was so exciting! Some of the pieces I developed for Club Zebra were “Mad at Miles,” “In the Time Before the Men Came,” “Robin & Mike,” and so many others. Some of Zeke’s pieces were “The Summer They Started Killing My Friends,” “Jersey Turnpike Blues,” “Power Door Locks,” and “Bop ’til You Drop.” We also did a number of pieces together, maybe most notably WNTV, which was a newscast that gave political and cultural news from around the Negro world.

Club Zebra, ca. 1990, vintage photograph [photo: Sue Ross; courtesy of Pearl Cleage and Zaron W. Burnett, Jr.]

Zeke directed the pieces I did at Club Zebra, often bringing in [archival] video (such as our completely unlicensed use of Richard Avedon’s photographs of Miles Davis!), [set-dressing], and original video that he directed and shot with D’Angelo Dixon, our intrepid videographer and master of all things technical.

The use of a big screen to project our original preshow video—with music of [different] scenes around Atlanta, sometimes including us—was also Zaron’s idea. He wanted to project us to the audience as “bigger than life” in the preshow videos, so that when we came out to perform, they already had an idea of us being worth watching, since they had been watching us on video while they settled in for the show. The 10 years we did Club Zebra were transformative for me as an artist. I felt absolutely free and safe to say whatever I had on my mind, including my awakening feminist consciousness and my increasingly bohemian moral code. Eventually, we also presented some other performance artists, including Rhodessa Jones and Idris Ackamoor, Robbie McCauley and Blondell Cummings. But the most fun was always the shows we did ourselves.

Edward Austin Hall has worked with ART PAPERS since January 2013. He writes journalism, poetry, and fiction. He created Attend, the original calendar of arts events for artsatl.com, and he has been a regular contributor to burnaway.org. He served the nonprofit Eyedrum Art and Music Gallery as host of its monthly literary forum, Writers Exchange; as an organizer of Eyedrum’s annual eXperimental Writer Asylum; and as a board member and officer for almost a decade. His work has appeared in Newsweek and Code Z: Black Visual Culture Now. He wrote the Dictionary of Literary Biography entry on cartoonist Alison Bechdel. Hall co-edited ART PAPERS’ 2017 special issue on author Philip K. Dick, as well as Rosarium Publishing’s 2013 anthology Mothership: Tales From Afrofuturism and Beyond, which The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction suggested might be “one of the most important sf anthologies of the decade.”