Maria Artemis and Eleanor Hovda: Labyrinths

Share:

“Labyrinths,” a multi-media installation by Maria Artemis and Eleanor Hovda, was created to raise awareness of the ways in which our bodies are objectified and experienced. The works, which have structural as well as metaphorical significance, incorporate anatomical and architectural elements within a larger existential context.

As Artemis and Hovda state: “There is no fixed locus or source of human perception, but rather ongoing flows of sensory, intellectual, emotional, biological, and spiritual energies which create awareness and understanding which are also in constant flux.” Artemis and Hovda address these issues through two-dimensional framed works and sonic and sculptural installations.

Artemis’ framed studies use images appropriated from her mother’s Gray’s Anatomy. Her mother was a physician, and Artemis draws fragments from the book to use as the structural basis for her work, which makes autobiographical references. Artemis compares anatomical objects such as pelves with architectural spaces like atria and asks us to compare these relationships through our own bodily experiences. Artemis frames and enlivens anatomical drawings with painting, using red, black, and yellow as her basic colors. The color and expressive application of the paint is stark, confrontational, and direct, highlighting the complexity of the drawings. These paintings show the precision as well as the limitations of academic, analytic, linear, and structural forms.

Three small wall constructions, Three Views of the Brain, extend the two dimensional labyrinth of the drawings and paintings into the sculptural arena. These three works highlight illustrations of the cranium, one including the inner ear, through a sculpturally evolving three dimensional metal frame attached to the wood. To this frame is attached copper wire, foil, and three wooden paddles in different colors covered with beeswax, resulting in a sensuous, buttery surface. These works emphasize the idea of a “playful foray” into labyrinthine territory and present as a pivotal transition—introducing us to experiences on a smaller scale that are embraced in the larger sculptural pieces in the atrium. Music composed by Hovda played throughout the exhibition, acting as connective tissue.

Labyrinths, a soundscape, manipulates and mixes sounds obtained from playing the objects in the exhibition. The materials and objects are redwood planks used as marimba keys, copper or PVC tubes that are blown like trombones, copper plumbing joints struck like bells, metal rings tossed on the floor, metal sheets shaken to mimic thunder, and glass beakers rubbed with wet fingers or blown. John Lancaster, Artemis, Hovda, and Peter Sawyer, Artemis’ son, are the musicians. Hovda, in creating her sound environment, imagines “both the inner and outer soundscapes which might occur when one traverses a labyrinth.” These sounds were taped, edited, and remixed to create a sonic work that emanates from a room in which people are encouraged to sit, snack, and relax. Here, music is heard while the works in the atrium are viewed through the glass divider. Like the heart, the exhibition has different chambers.

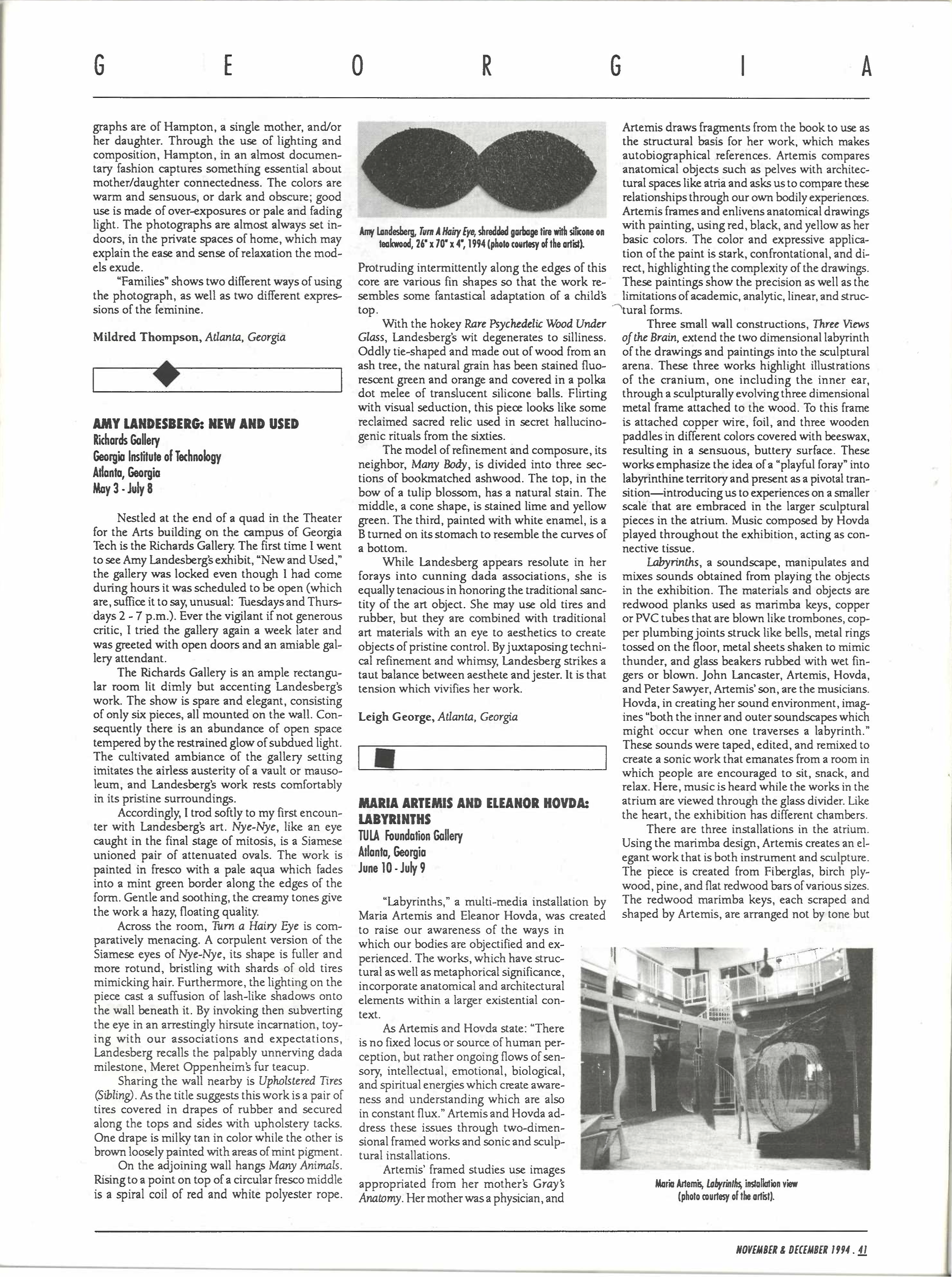

There are three installations in the atrium. Using the marimba design, Artemis creates an elegant work that is both instrument and sculpture. The piece is created from Fiberglass, birch plywood, pine, and flat redwood bars of various sizes. The redwood marimba keys, each scraped and shaped by Artemis, are arranged not by tone but by form. In this way Artemis allows the form of the sculpture to determine the scale and incremental sound of the instrument. The marimba has a vertical extension resembling a harp or a mast, from which two galvanized sheet metal teeth extend horizontally. These, along with the redwood bars, are used to create sounds. The horizontal extension mirrors architectural elements in the atrium. Next to the marimba is an installation constructed of orange fishing net covering a human sized tunnel supported by copper tubes. The net structure is then composed of voids rather than solids, resulting in a lightweight support system not unlike a human skeleton. The net-covered pathway is intended to be navigated by humans in a similar manner to a foreign body entering the bloodstream or the alimentary canal. This creates a different bodily experience from that of two dimensional drawings and paintings. The tunnel extends the eye to meet a descending spiral staircase and embraces it within the context of the artwork, integrating another architectural and structural context. The final work, small and easily lost among the other two installations, hangs high in a corner. It is a sound piece that the viewer activates by swinging a rope, which hits a cigar-shaped piece of redwood against an I-beam. This metal support is structurally necessary to the TULA building, so the interconnectedness between the art environment and the building structure is explored. The sound resonates through the atrium. As the ear follows the sound the eye is reminded of the attention to detail of these works—the wood grain, the rope knots, and the care with which these sculptures are constructed.

These installations are as much an integral part of the environment as they are separate, just as the painting in the framed works is as much a part of the structural elements of Gray’s Anatomy as it is apart. The only difference is that the installations involved our bodily senses more whereas the framed works involve our visual acuity.

The installations are constructed through the reflected actions of Artemis and Hovda. The framed works in the gallery provide the syntax for the installation, which enlarges to include sculptures and the architectural elements of the building itself. Plastic associative images evolved through the accumulation of actions over time into a montage of possibilities. The reflective action grounded in the lives of the artists and those in the working community at TULA create a narrative world where the desire for an awareness of understanding of life motivates a process of continually renewed contemplation. The participants step in and out of different frames of reference and over time interpret the work from multiple viewpoints. This is the aspect I appreciate most about this particular exhibition.