Interview with Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Box Spring in Tree) from Sea Islands Series, 1991-1992 [courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, P·P·O·W, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS May/June 1993, Vol. 17, issue 3.

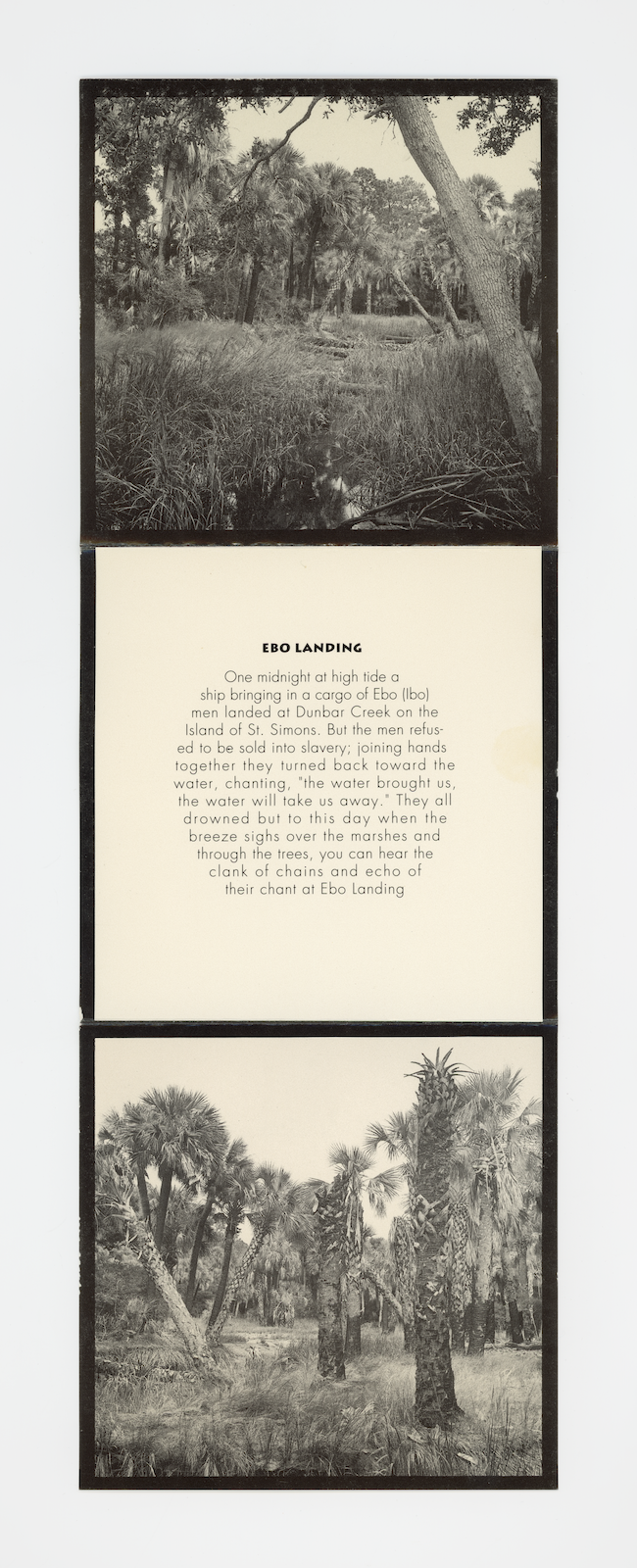

Born in Portland, Oregon in 1953, Carrie Mae Weems is a graduate of Cal Arts and the University of California, San Diego. She also studied Folklore at the University of California, Berkeley. As an artist who utilizes photographic media to visualize her work within conceptual exhibition whose formal context creates an environment for her thematic concerns. Family Pictures and Stories (1978-1984) consists of numerous photographs of the artist’s extended family, arranged like snapshots in a walk-in photo album, and accompanied by her reminiscences and retelling of family tales. In Ain’t Jokin (1988-1990), Weems illustrates racist jokes with a literal directness that confronts the viewer with offhanded bigotry while simultaneously implicating him/her within the social praxis of such activity. Turning from the manner in which racial intolerance is manifested and passed along via language and cliché, in Colored People (1990) Weems explores the dual nature of caste and color within the African-American community. While these series most often combined photographs with text, in And 22 Million Very Tired and Very Angry People (1991), first exhibited at The New Museum of Contemporary Art, Weems fills a whole room with large format polaroid prints and red banners, each with a different text. The result, which physically compels the viewer to look not only at the images but also up at the banners, allows for a multitude of readings and voices. In Untitled (1990) shown at P.P.O.W. and at the 1991 Whitney Biennial, Weems creates a fictitious photo-narrative whose often humorous but emotionally intense story of a romantic relationship reflects the artist’s concern for visualizing the lives of African-American women. For her most recent exhibition at Nexus Contemporary Art Center and P.P.O.W. (1992) Weems joins images of the landscape and the inhabitants of the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia with texts derived from sources such as cookbooks, songs, nursery rhymes, and folklore to explore the nexus of inheritance and racial myth. A major retrospective of Weems’ work opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in January 1993.

Susan Canning: One of the things that I find interesting in your work is the aspect of sight and the use of space. In Family Stories, for example, it’s almost like entering into your family photo album. And 22 Million Very Tired and Very Angry People is a whole installation. In other pieces, space is formed through the construction of a narrative between the various photos, creating a space almost like an envelope, or bookends. Do you think that there is a kind of site or space in your work?

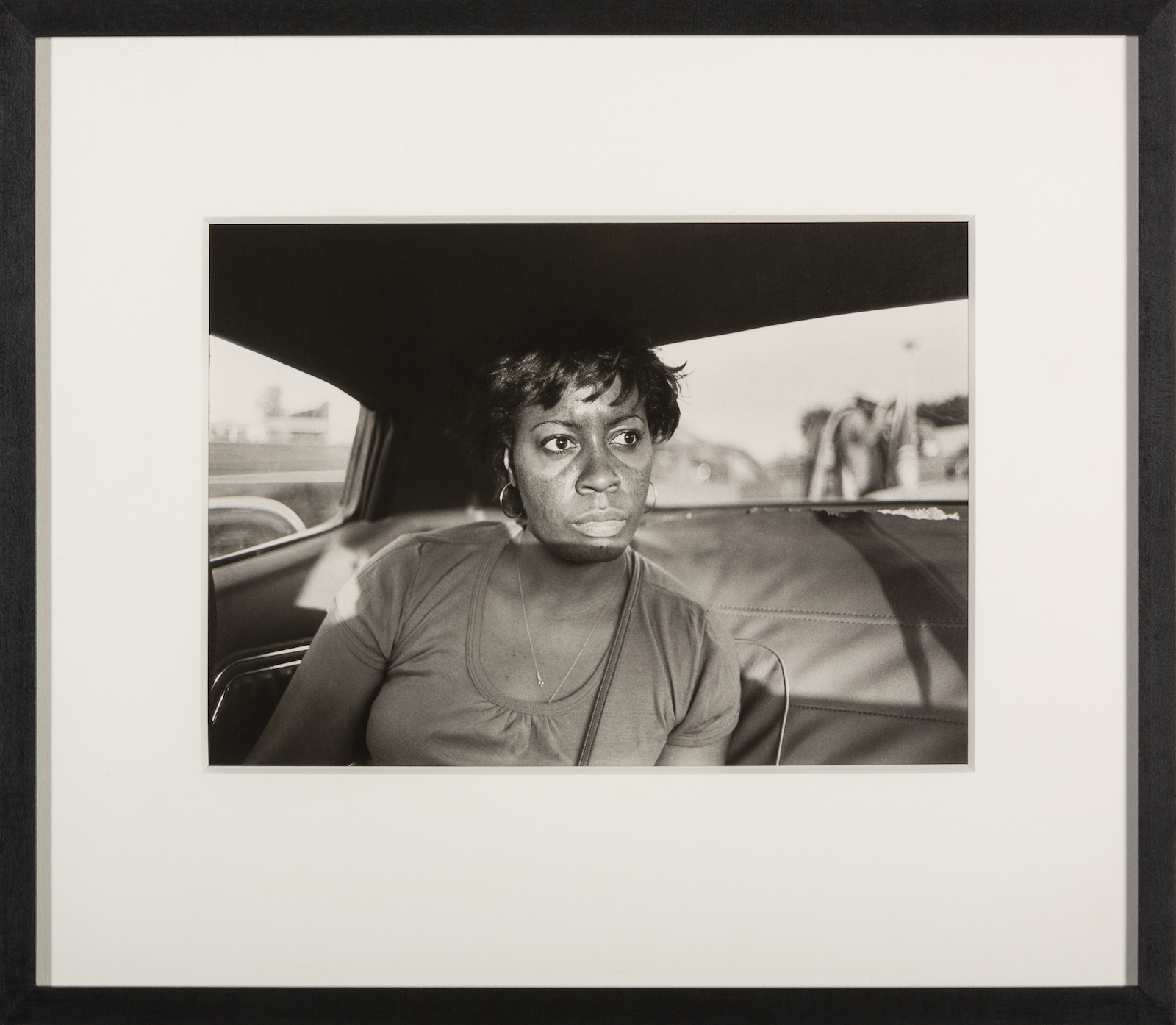

Carrie Mae Weems, Alice from Family Pictures and Stories series, 1978-1984 [photo: © Carrie Mae Weems; courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Carrie Mae Weems: I think there is a psychological space created for myself and the viewer. It’s a psychological space that works when you’ve found its rhythm. That’s the thing that allows you to move through it and to feel wrapped up in it. It’s like listening to music. Trinh Minh-ha says in “Living in the Round” that everything about the space where people live their lives had to do with the rhythm of the space. You know when people were working on chain gangs, there was a lead singer and a pulse beat was constantly going that established a psychological space for you to enter so that you could almost forget about what you were doing. I am interested in that thing, whatever that “thing” is. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. But I think that there can be, whether it happens in my work often enough is questionable, but there can be a real solidity and a wonderful sound, a visceral sound, that takes place between how the text reads as a piece, whether on a wall or hanging from a banner and how it crosses the room to meet up with another photograph. I think that I am very interested in that, probably all artists are, sort of surrounding the viewer and yourself in a world to deal with very particular ideas and notions. You have to be into the mess of the thing.

Canning: What about the authority of your voice—that it’s female, that it’s African-American, that it deals with issues of class, that it’s vernacular?

Weems: I think it’s simply my way of sounding out and allowing a certain resonance to take place that wouldn’t otherwise. I don’t think about it from an “I” position, I feel it’s a communal voice, a voice of a group, a voice of a class, and I know what that voice sounds like because I’ve come from that group, that class. I know what that language is. I suppose I’m usually thinking of it as that collectivity.

Canning: And the collective voice is female, African-American.

Weems: Well, it is and it isn’t. There is often a male’s voice that intervenes, that has to be there. It makes sense because then you have to deal with the mess of things. There could be a clearly defined, delineated female voice, and then there’s sort of a male voice. For instance, the male voice in Untitled is really wonderful. Without his voice in the shit, it wouldn’t fly, it wouldn’t go anywhere. There’s definitely something that she’s on to, but he has a say in her shit too, about how it’s going to fall. And her position is to move back and give him room to speak. And in 22 Million, it is a conglomerate of voices, all kinds of voices, coming from all over the place, and it’s not always a black voice. That’s probably the one I feel most comfortable with. I love the idea of penetrating the “king’s English,” but that’s not the only thing. I think people would prefer to think about it as being the only thing because then it contains me, in what I call “nigger space,” but I really don’t want to stay there because that’s not all of who I am.

The things that interest me and the things I try to play around with have to do with the quality of certain kinds of voices from certain kinds of places. Probably more often than not, it’s a female voice but it’s not always a female voice and it’s not always a black voice. I guess that the notion of the multiplicity of sound in a voice is crucial and probably one of the most important things to me politically and socially.

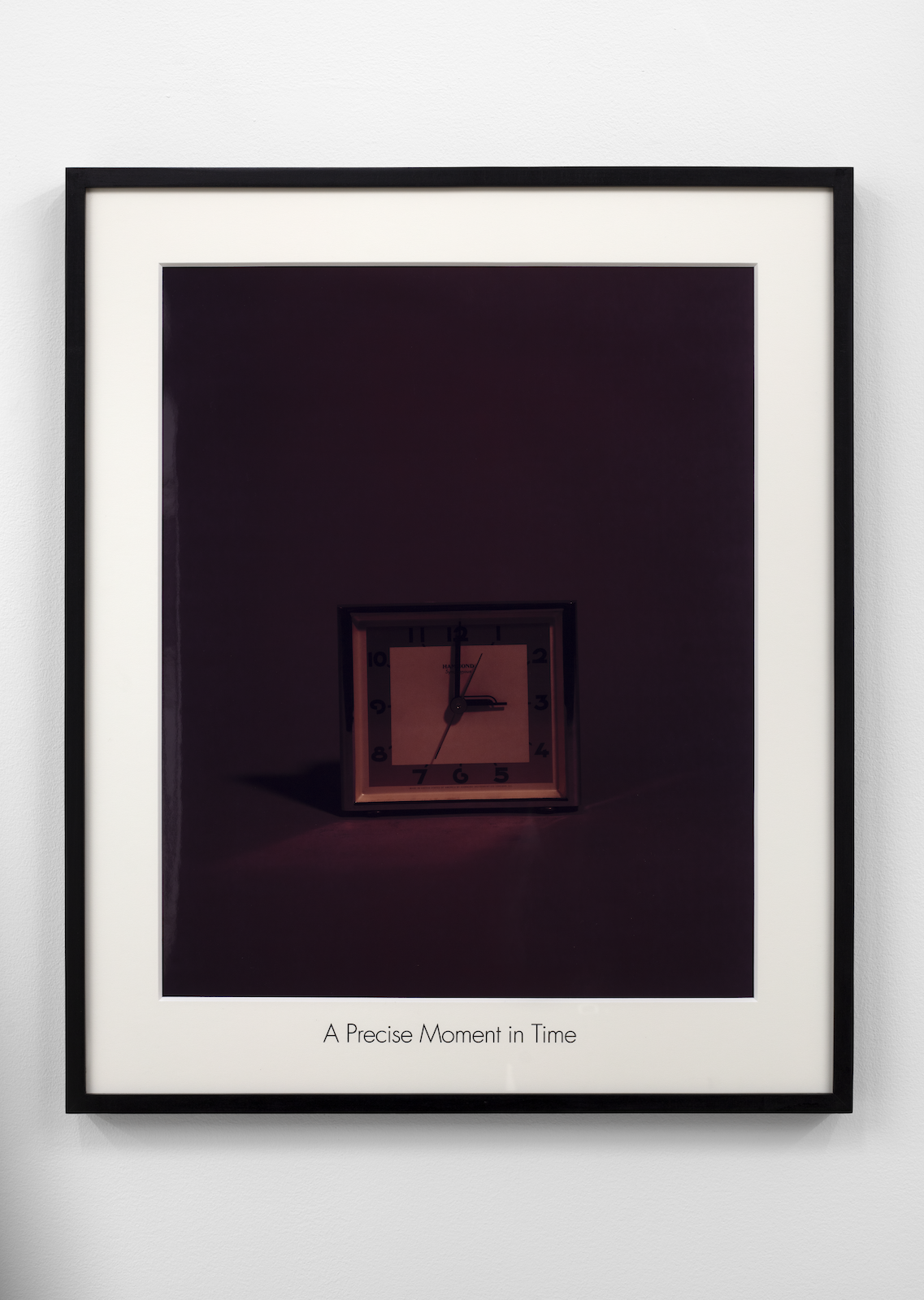

Carrie Mae Weems, A Precise Moment in Time, 1991 [photo: © Carrie Mae Weems; courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Canning: But nevertheless, the voices that you activate aren’t authorized, aren’t given their due.

Weems: It’s like penetrating the “king’s English,” but that’s not the only thing. The reality is that we are living in a democracy where most of us are supposed to be silent. That’s what democracy is, right? So that anything that intervenes in that is a certain kind of amateur authority. But the thing that is remarkable is that we all claim space, all peoples attempt to claim space. Whether you do it through rap, etcetera, how you speak is the important thing. The issues of activating voices, or giving them authority, I don’t really care about that so much as intervening, just intervening in a certain kind of way, warning to say a certain kind of something, and hoping to get heard. Probably 99% of the time it doesn’t, but sometimes it does get heard. Sometimes it falls just on the right drums at the right moment so that something might happen, something may pull you, the audience, me even, to initiate some kind of action based on the quality of that sound. It’s like listening to Martin Luther King speak and then going out and organizing a bus strike or something. Things can get done.

Canning: So you see yourself as a catalyst and your work as being a catalyst?

Weems: It has the possibility of being that, under the right circumstances. It certainly gives you pause. There’s some stuff you have to deal with when coming to the work, and then once you leave there are some things you have to think about and then you go home and talk to your husband, or your kids, your boyfriend. It does something, it’s not just on the wall.

Canning: Where do you interject your own language?

Weems: The collective and the I are both in there. You can’t talk about something unless you’ve experienced it on some psychological or physical level. So that’s where I think I come in, as a certain conduit for a kind of experience, because I’m a real working class girl, a “cotton-picking, corn-pickin negro,” you know. I know what experience is, it’s not abstracted from some Marxian text.

Canning: I see a change in the location of the voice, from the narrator in Family Pictures to a more declarative voice in Ain’t Jokin, to a cataloguer in Colored People, to an orator or dissident in And 22 Million Very Tired and Very Angry People. Do you think this is true?

Weems: Yeah, because in each piece, voice and text has a very particular role to play. In Ain’t Jokin I’m really just pulling from Anglo-American folklore, as opposed to Family Pictures and Stories where I am pulling from my mother’s memory, as opposed to 22 Million which pulls from history and direct quotation, not folklore. Each piece demands a very particular kind of voice. My family’s stories would be completely inappropriate in 22 Million. It just wouldn’t make any sense, that quality of sound wouldn’t make any sense. I think in that piece it was really important to rely on the viewer’s and the reader’s sense of pacing. When you read it you have to have a certain sound too, a certain voice. It creates its own space in some ways for each individual.

Canning: What about the way the text positions the viewer to read and see. I assume that you purposefully implicate the viewer. How did you get to that point?

Weems: I think it happened fairly early on, in trying to deal with the issue of spectatorship, in where are people placed in trying to bring them into it. If you decide that we are all party to the crime then it makes sense that we all are held accountable. You could then point to the viewer and say “you” and “us” as opposed to “they.” The thing that troubled me more about the advent of postmodernism is that there is always a “they,” “them over there” sensibility, but its never about us and how we fucked up, how we allowed a certain amount of victimization to take place to begin with.

Canning: It’s not only implicating the viewer but also activating the viewer

Weems: You have to move around a bit. You have to do something.

Canning: So it’s not passive. Do you see that as a part of the politics of it?

Weems: I’m not sure if I’ve really thought of it in that way. I like the idea of the viewer being active. I’m a political artist, that’s what I do. There’s a part of making that’s quite wonderful. The aesthetic experience is a wonderful experience, but that’s certainly not enough. But it’s what viewers come away with, what they learn, what they understand, that they begin to question, that matters most to me about being involved in the whole thing. It goes back to your earlier question, that matters most to me about being involved in the whole thing. It goes back to your earlier question, about the work being a catalyst. Well hopefully a catalyst to memory, a catalyst to some sort of action, a part of a force, a movement for something bigger. It’s only a drop in the bucket , relatively speaking, but I think it grants a sense of unity since each of us can contribute our small part that will make up the total, right? That can effect change, then that becomes our moral obligation. You strike where you can. Hopefully it’s just enough to rock the boat, just enough to ask some real fundamental questions. And maybe it isn’t. Maybe I’m fooling myself, but I’m really hoping that it asks the questions that need to be asked. Not that the work needs to ask, but that we as social beings trying to figure out how to live on this god-damned planet need to ask about how we go about doing it.

Canning: And you do that through actively implicating the viewer. For example Ain’t Jokin’ are photographs of very literal images and really awful racial epithets or jokes, so that there is no way that you don’t get it.

Weems: Because that becomes the shit, that really becomes the shit. You know there have been more mamas than we can shake a stick at that look at their kid and say, “you ain’t never going to be the shit,” and there is everything youve ever thought of when you see a black person with a watermelon or a chicken. You know we all occupy a position relative to the stereotype. That’s what I think is interesting about that piece.

I think it’s probably the best piece I’ve ever done. It’s so unmediated. It’s just so naked. That’s the thing that upsets people more than anything. It exposes the wounds so deeply. I think that’s one reason they try to ban it as much as they possibly can. On the other hand, people try to show it as much as they can. There’s a real issue about that work. It’s very uncomfortable, but then dealing with our real shit is always uncomfortable. But I think that idea of occupying a number of different sites, that there are a number of different sites to be occupied around a given body of work is a very interesting idea.

I suppose that the same thing is true through no matter what the work. I mean, a black family experiencing Family Pictures and Stories has a different thing to say to me than a white person experiencing the work. And certain black people find it really offensive, depending on where they are coming from. So this idea that you try to hum a collective voice is an important idea, but yet you always have to get more specific—”well whose collective voice are you talking about?” “What voice are you talking about specifically, dahlin,” since each of us does occupy many different sites, locations, positions. I suppose this is what I’ve been thinking about more and more. I think that the movement has to be toward a united front, so that you form collectives upon what is agreed upon. It’s a limited partnership, but it’s there.

Canning: What was the reaction to Colored People? My own reaction was that it has that double take, because on the one hand it was dealing with issues of castes, of power and hierarchy, but at the same time they are incredibly beautiful in color and tone. And the naming of color, from a white person’s point of view, is all about the beauty of the color. So there is a double message, a double language, a double thing, because it is also a way of selecting, of saying one is better than, or one is less than. Yet at the same time, it is part of the culture–how people name you or describe you. But in a certain way you are also implicating this selection as creating the system.

Carrie Mae Weems, High Yella Girl from Colored People series, 2009-2010 [photo: © Carrie Mae Weems; courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Carrie Mae Weems, Magenta Colored Girl from Colored People series, 2009-2010 [photo: © Carrie Mae Weems; courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Weems: It doesn’t create the system, it expresses the system. That’s very different. And then it takes the system out. So you can start out with “High Yellow” and “ Magenta.” It becomes the way caste is in place but is also completely ridiculous and wonderful. That it sort of folds in on itself, that it critiques its own language, and its own position. It’s just like this little drop of color. It doesn’t matter which one you are. They’re all crazy, they’re all wonderful, they’re all different. I get every kind of reaction. People are interested in them. I mean they are all beautiful, they’re all children. There’s nobody in there over 18. That was one of the points of dealing with the idea of color as it exists among young children, young people as they struggle to get their identity. There hasn’t been any controversy. Nobody has written about them.

Carrie Mae Weems, Black Woman with Chicken, silver print, 1987-1988 [photo: © Carrie Mae Weems; courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Canning: There is a certain irony in your work. What would you say is its role in your work?

Weems: To point up irony, that which is ridiculous, that which is nonsensical. To get to the wit and humor of it, because it’s all of that which makes it understandable and approachable. I think it’s the irony that makes it approachable.

Canning: How do you see humor as working in your art?

Weems: I think that the work is deadly serious, except that it uses humor to bring you into it. It’s like telling a joke at a party, it breaks the ice. You tell a joke and they tell a joke and then a whole series of conversations can ensue from that place. Like they say, sometimes you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar. I think that that’s true. First of all, I love humor, just because I think it’s great, but also, as in folklore, it becomes a way to deal with very difficult issues that we wouldn’t ordinarily feel comfortable broaching or dealing with. So it provides us with a kind of arena once again to discuss the undiscussable in a way that is socially sanctioned through humor, through irony, proverb, or any other folklore element. I think that’s its importance, its beauty and its wonder, that it allows us this very special space to interact.

Canning: That tension is what I found provocative. For example there is a certain absurdity in Ain’t Jokin’ of that literal image of a woman with a chicken.

Weems: They’re really hilarious. The humor is much more wicked because it has much more to do with the insidious nature of the devastatingly real effects of humor on a race of people. Because the jokes were not just used as a social barometer to talk about black folk, it’s been used as a way of annihilating them and keeping them completely in check. So it’s no wonder when they walk through Brooklyn to protest the death of Yusef Hawkins that they’re waving watermelons and chickens at the people passing through.

Canning: But in the juncture between those two points you laugh and yet you catch yourself at the same time.

Weems: Yeah, well that’s the nice part of it. Because hopefully what you realize is that you’re laughing, but then what are you laughing at exactly? Why is this funny? Why is it not funny now, but it was funny last night when my girlfriend told me that joke? That’s the shit. Because humor circulates in very interesting patterns.

Canning: Lets move to your concern for social issues and social change. I read that some of the issues you are interested in were revolution, African-American achievement, civil rights, and affirmative action. Would you say that those are the main issues of concern?

Weems: I’ll just say, those and other. Lets keep it open, as concerns are always spiraling out. I think the idea is that if you can operate within your given sphere, as a catalyst, then there are possibilities—simply that, that there are possibilities. Because we all know essentially that something’s got to give. Now what is it exactly? What one does then is to posit some possibilities about what it might be, where it might go, what might be some things we need to consider along the way. So I think that where maybe I am starting from is trying to understand the relative place of a new kind of democracy. I’m really interested in this idea of forging a very different kind of democracy that has as its base a highly developed sense of what is possible on the planet with all of us living on its different needs, desires and aspirations. How do we take care of our own? How do we take care of our constituencies in mind that we might not completely agree with? It’s slow in coming, but it’s worthwhile. And that we are in the process of change. So to talk about the future is ridiculous, because the future is now. It is a part of now.

Invitation Card for Carrie Mae Weems, Sea Islands, 1992, at P·P·O·W, New York [courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York, P·P·O·W, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin]

Susan Canning is a writer and art historian living in New York.