Sheila Pree Bright’s Suburbia: Where Nothing Is Ever Wanting

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 11, 2004, chromagenic print, 24 x 30 inches

Share:

This essay was originally published in ART PAPERS July/August 2007, Vol 31, issue 4.

For the past two years, Sheila Pree Bright has been photographing affluent, African-American suburban homes around Atlanta. Suburbia, the resulting series of forty images, conjures elusive narratives of socio-economic and racial identity through details of architectural design and interior décor. The actual homeowners appear infrequently in the work, and never as specific individuals. Suburbia‘s subject matter, upper-middle-class African- American lifestyles, is both largely invisible in mainstream media and familiar to her. However, Bright does not uncritically assume the transparency of either her subject or her medium. A definite sense of self- consciousness—on the part of both artist and homeowners—pervades Suburbia: each photograph is exquisitely composed, with clean lines and diffused lighting matching the casual elegance of the suburban homes. The placement of objects and figures appears to be the result of both happenstance and calculation–a paradox that holds the work in delicate tension.

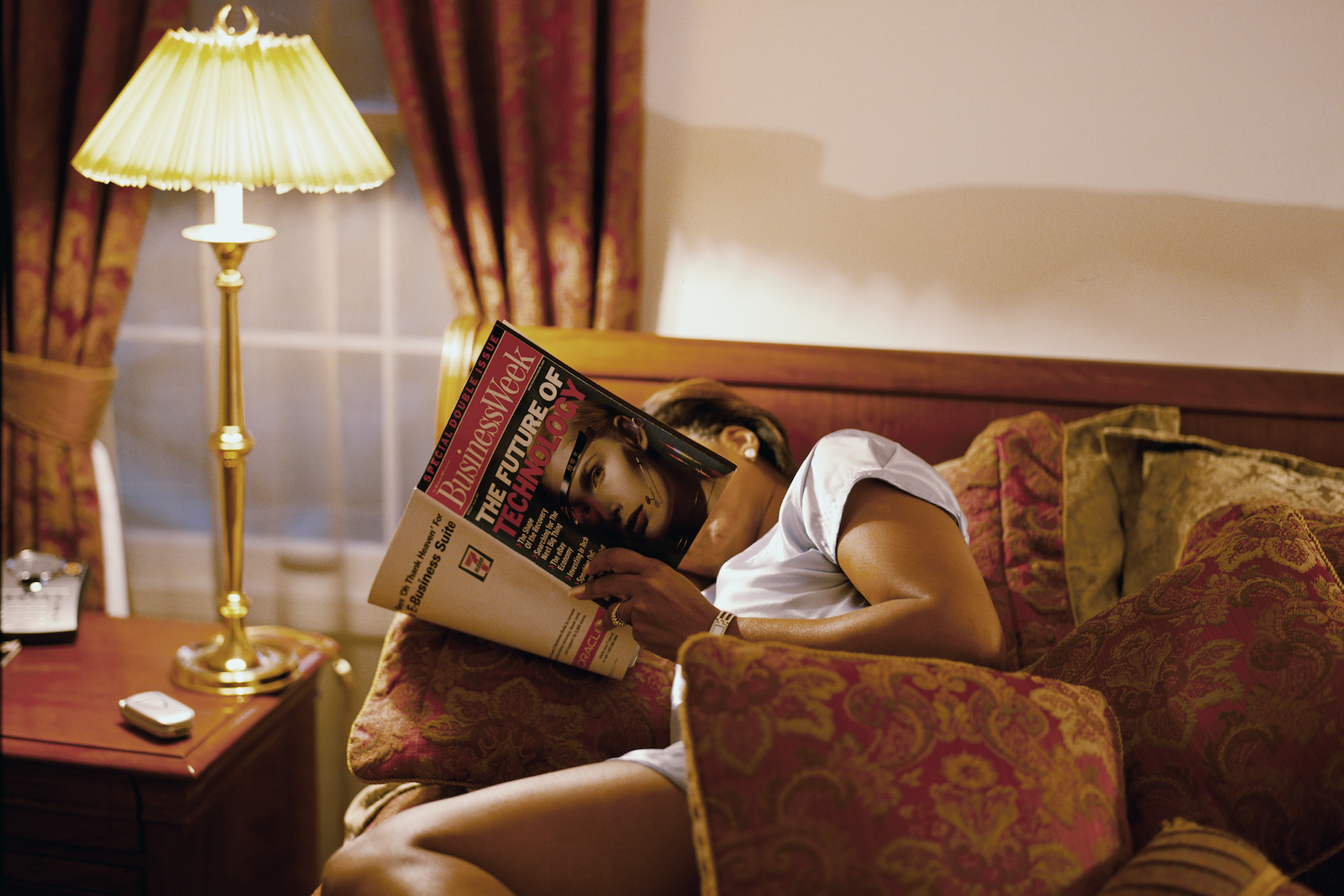

Though bound by common threads, the narratives that emerge in Suburbia remain individual and private. Neither the communal aspects of suburban life nor its social ills feature in this process. The series also avoids trafficking in familial drama: no hints of violent conflicts or secret trysts face in an appeal to voyeuristic pleasures. Untitled #12, 2005, epitomizes Bright’s understated approach. A woman casually reclines on a living room sofa her face partly covered by the “Future of Technology” Business Week issue she reads under the warm glow of a table lamp. The upholstery’s rich and gold tones envelop and virtually camouflage her, if not for her bright white t-shirt and the metallic glimmer of her jewelry. Though her entity is obscured, the woman is vital to the composition: her body and the magazine she holds create the diagonals that mitigate the dominant horizontal lines of the furniture. They also establish a parenthetical counterpoint to the vertical line of the lamp, providing balance between the two sides of the image and focusing attention to its center. Above all, however, the woman’s mocha skin tone remains a conceptual focal point, quietly but insistently registering Suburbia‘s raison d’être.

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 12, 2005, chromagenic print, 24 x 30 inches [courtesy of the artist]

In the absence of a figure, household objects allude to the homeowner’s racial and cultural identity. In Untitled #34, 2007, a kitchen countertop displays an array of wares, including several objects of the African Diaspora: a tableau of miniature Brazilian Maracatu dolls and two 1930s tumblers decorated by artist Carew Rice sit near the sink, while a Jamaican saltshaker rests on a shelf above. As collectibles, these items attest to histories of physical and social displacement, and to cultural adaptation and racial hybridity. In this otherwise unremarkable suburban kitchen, they evoke alternative tropes of home and domesticity, countering the characterization of suburban cultural and racial homogeneity.

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 34, 2007, chromagenic print, 24 x 30 inches [courtesy of the artist]

In other instances, the objects open onto American youth culture. In Untitled #16, 2006, a shoe rests on the edge of the fuchsia bedspread. It only takes a moment to recognize the Air Jordan, its teenage owner reduced by the camera lens to a blurry form at the picture’s edge. A bit of urban fashion, the sneaker collapses social demographics, attesting to the ways in which suburbanites often aspire to emulate their inner-city peers. But Untitled #16 affords a new twist on this phenomenon, since it has typically been the province of white suburban teenagers purchasing products originally marketed by and to inner-city African-Americans. With this one object, Untitled #16 invokes a plethora of associations concerning shifting socio-economic and racial relations in contemporary culture.

The occasional appearance of old family photographs also yields clues to the homeowner’s identity. In Untitled #27, 2007, a framed black-and-white double portrait of two black women rests on a closet shelf, surrounded by boxes and military items. Beneath, a row of uniforms indicates a life dedicated to an Army career. The photograph appears to be from the turn of the last century: the women’s formal poses and high-collared white blouses evoke a bygone era. While relegated to the closet, they are not entirely forgotten; though anonymous to the viewer, the women are presumably familiar to the homeowner—family perhaps.

Such use of a picture-within-a-picture is a recurrent and telling feature in Suburbia. Bright uses this device as a trope to frame racial identity. In turn, this illuminates one of the series’ conceptual tensions. On the one hand, Suburbia calls upon photography’s evidential value to dispute media characterizations of African-American identity as primarily urban, violent, and poverty-stricken. In this regard, the series brings into public focus a photographic tradition that has for the most part existed only in the private realm of African-American homes. Feminist scholar, activist, and cultural critic bell hooks has written about the historical and social importance of family photographs in black households, characterizing this visual practice as a critical intervention in the representation of African-Americans in popular culture. Governed by a sense of intimacy, harmony, and respectability, photography afforded African-Americans a means to forge a pictorial genealogy of decolonization. Writes hooks: “We saw ourselves represented in these images not as caricatures, cartoonlike figures; we were there in full diversity of body, being and expression, multidimensional.”1 In their depiction of the domestic spaces of black, middle-class existence, Bright’s photographs may present a variation on this theme.

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 27, 2007, chromagenic print, 30 x 24 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Suburbia also demonstrates that attempts to wrest narratives of identity—racial, familial or otherwise—from photographs require extradiegetic leaps. Resorting to knowledge and experience beyond the image, some of these leaps jarringly expose the viewer’s unconscious recourse to racial assumptions. This is most clearly registered in images such as Untitled #11, 2005, where ethnic signifiers are absent. Here, one would be hard-pressed to state with any certainty that the pink houses’s occupants are African-American. Race only comes into focus by linking this work to the other images in the series. Even then, the connestions remain tenuous at best—a compensatory gesture. The absence of clear signifiers has caused some viewers to take issue with the work. Bright claims it was unintentional on her part. This, however, does not lessen its significance for the reception process. Rather, this initial uncertainty reveals itself to be crucial, as it highlights questions that course through the entire Subrubia series: how does racial identity get inscribed in spatial aesthetics? Or in a photographic image? Likewise, why do we, as Coco Fusco asserts, “like to see race even if we don’t consider ourselves racist?”2

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 7, chromagenic print, 58 x 48 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 8, chromagenic print [courtesy of the artist]

Fusco offers a couple of answers: consuming racial imagery is a phantasmatic substitute for a direct engagement with the realities of race relations; conversely, the circulation of representations of non-whites feeds the assumption that racism is obsolete. Fusco capitulates to neither justification, nor does Nicholas Mirzoeff, who offers further insight into the issue when he analyses the racialization inherent in the interpretation of a photograph. He suggests that photography has functioned historically as “a prime locus of the performance of the racialized index.” The medium continues to picture racial difference as a truth, despite contrary biological evidence. Mirzoeff writes:

By performance, I mean to suggest something that is constituted each time it is enacted and that may vary according to circum- stance. As race is not an indisputable fact, the index here is posed as a question of the race difference in which all citizens of the United States are skilled readers. Each time a photograph is looked at, a viewer consciously or unconsciously decides whether and how it indexes the race of its object.3

Mirzoeff’s characterization of skilled racial readership indicates how recourse to difference, rather than sameness, governs the reading of photographic representations. In Bright’s work, the occasional absence of the racialized index sticks out for the viewer. This may prove troubling to those to want—perhaps for the reasons Fusco imputes—identity to be more clearly inscribed in both the domestic and photographic spaces of Suburbia.

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 28, 2007, chromagenic print, 58 x 48 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Ultimately, however, Bright’s series speaks to the self-conscious performance of class, leaving a lasting impression of socio-economic identities carefully buttressed by the tasteful consumption of luxury homes and domestic goods. Conveyed through Bright’s lens, the results are appealing: the seduction of these insular, upper-class lifestyles merges with the artist’s photographic talents to construct the illusion that nothing is ever wanting in Suburbia.

Susan Richmond is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary in the Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design, Georgia State University, and has been a frequent contributor to ART PAPERS.

References

| ↑1 | bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, New York: The New Press, 1995, 61. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Coco Fusco, “Racial Times, Racial Marks, Racal Metaphors,” in Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, eds/ Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis, New York: Abrams, 2003, 23. |

| ↑3 | Nicholas Mirzoeff, “The Shadow and the Substance: Race, Photography, and the Index,” in Only Skin Deep, 111 |