Laying Hands on Texts

Share:

Longtime ART PAPERS copy editor Ed Hall and I have had countless discussions about grammar, punctuation, writing style, and what it means to edit the words of another. We delight in case-by-case evaluations of a revision’s impact on legibility, meaning, and accuracy, but we also tend to regard the author’s intention as sacrosanct. As we edited texts for the spring 2020 issue, with the theme Art of the New Civil Rights Era, Ed and I re-evaluated and ultimately revised the ART PAPERS style guide entry regarding the terms Black and White, when used as signifiers for racial identity.

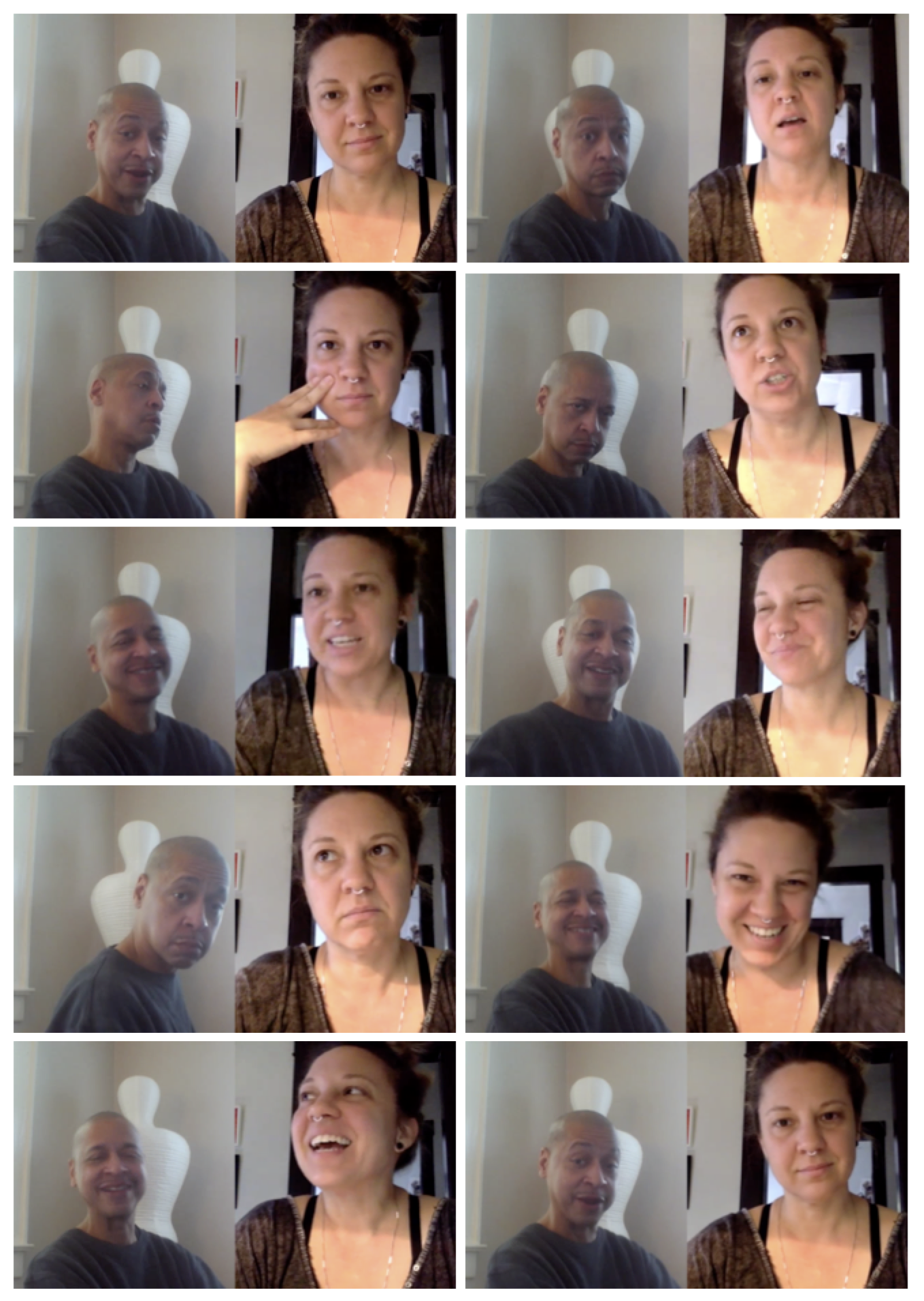

As we completed the issue, Ed suggested we share some of our thoughts about this decision and others, so we met virtually, in keeping with the times.

Sarah Higgins: Can you tell me about how you came to work as copy editor for ART PAPERS and how our current style guide came into being?

Ed Hall: My friend Cinque Hicks served a stint as the editor of the magazine before the long chain of guest editors. [Once that series of editorial handoffs] started to happen, I was told that people at the magazine were interested in some sort of continuity being brought to bear, issue to issue, that the style was all over the place. And at that point I had already redone the style manual for the now largely defunct/morphed-into-a-different-entity game publisher, White Wolf, which was based in Tucker, GA. The ART PAPERS style manual was a very different thing, as it was a journalism outlet style guide as opposed to one for what amounted to a fiction publisher. So it had to address lots of issues involving, for example, race, proscribed terms, terms to shy away from, and one of the first things that I was asked to do, as I recall, once I came aboard in the role of—I think my title then was edition manager—one of the things I did early was to overhaul the [existing] style manual and, in doing so, the question came up: Do we want to capitalize the informal terms for race? Now—

SH: Specifically, the terms Black and White?

EH: Probably, yeah ….

One reason that I felt … it was okay for me to come down on the side of not capitalizing these terms, which I did, was, to cut to the chase, when you grow up in the 1960s, looking like me, in Mobile, AL, at the tail end of the Civil Rights Movement and you—literally, the first grade school I went to was a segregated diocesan school. When you grow up in the midst of that and the Black Is Beautiful movement, Black is not a term that refers to skin tone. It can’t merely be that. It cannot. It has a much broader meaning. And so, I grew up Black with skin like this [holds up hand], related to and surrounded by Black people, whom I loved and who loved me, and so by that reckoning Blackness was not about skin tone.

Black Is Beautiful: [Black] is capitalized [there] because [it’s] the first word in [a sentence], and it ends with an exclamation mark in my mind.1 Outside of that, it seemed reasonable to want to sap some of the power of it, maybe, purposefully. And part of that too, I hasten to say, was also the desire to not capitalize White.

SH: Yeah, I’ve noticed publications [that] follow the style of capitalizing Black and not capitalizing White. And maybe that’s something we talk about later as we get into the work we just did on the most recent issue, because it’s also something that our writers pushed back on.

EH: Understandably so, and yet there’s another rule that I also had a hand in that’s worth illuminating. You may have noticed that we do not hyphenate things like African American.

SH: Right.

EH: That was also a decision … I made, and [that] was influenced by something that happened in the Wilson administration. Woodrow Wilson was my least favorite president in the history of presidents, at least until recent times. He actually made the term—during his tenure in the White House—he managed to make the term hyphenate [into] an ethnic slur. That takes some doing!

… I did some research on it. Indeed, just as [today] there’s a movement about how Black should be capitalized, there was a movement [afoot as I was overhauling the style guide] that said, Yeah this whole hyphen thing is an undermining piece of grammar. And I thought, Hm, yeah. Then I saw the hyphenate thing in some history about Wilson, and I said [to myself], “Well, that’s reason enough for me.” So that’s where the hyphens went. Blame Woodrow Wilson.

SH: When I came in as editor—about two years ago, now—we started having conversations around individual instances of grammar, or punctuation, or particular turns of phrase. And then something else that we do, when possible, is to edit texts [while we sit] side by side, reading aloud. You read aloud, because we’ve found that I will correct things in my mind and with my mouth before they’re corrected on the page, which is troublesome. In editing that way, I’ve learned an incredible amount from you. I’ve also learned to articulate more clearly my appreciation for how language and the nuance of language is the root of praxis. That’s something I understood before, but never had anybody to talk with about it quite so technically. And one of our first conversations about the style guide had to do with—I just had a question about why we didn’t capitalize these terms [related to race]. I was surprised, understanding the sociopolitical position of the publication, that this was something that had not been addressed …. We talked, and ultimately I agreed, but I had to think it through at the time. And the reason I agreed was because I saw these terms, Black and White, as being social constructions. Yes, also identification terms, but ultimately ones that serve to enforce, to encapsulate, and place boundaries of legibility around social constructions that I felt were not always productive. There are far more—I would have said—destructive reasons to put a racial term on someone than there are positive ones. Maybe. Or at least, that was my thinking at the time. And I remember that conversation really clearly, [when] we talked about it. It wasn’t that long ago. And so I bring that up, just to kind of place this sort of timestamp on how quickly our thinking evolved around this question. And maybe evolution is the wrong term, right? Because who’s to say where the winds will blow this discourse.

EH: I can point to the historical precedent of the term hyphenate, used as an insult, guiding decisions I made. Was there a particular thing you read or something that someone sent to you that tipped the scale? Was there a tipping point on the capitalization issue?

SH: Yeah, I mean, I think for me, the tipping point was cumulative. It built. Every time I, as a White woman editor, downcased the capitalized-B [term] Black of a writer who identified as Black.

EH: I could see how that could do it.

SH: Yeah, and every time [I did] I found myself doing a negotiation that had to do with the adherence to a rule—a rule not written by me, but one that I had already questioned in conversation with you. We had worked through our rationale behind it. Which is, honestly, often what it takes for me to follow a rule. But I felt that I was having to over-rely on that past position.

That feeling of discomfort speaks to something that came up for me when I first started to be more aware of my own position in regard to race, in regard to how I wanted to move through the world as a White person. One of the first things that I really thought about was a realization that part of doing the work of—I mean, if you want to say allyship, or advocacy, or, you know, just being a good person—part of that work, I think, for White people, at the very beginning, has to be about getting comfortable with being wrong.

EH: Yeah, so glad you brought that up. We will come back to that from a completely different direction.

SH: Yeah, so I think what I started to feel was this building discomfort that maybe I was relying on a calcified position, that I should listen to the discomfort … I was feeling in making that editorial gesture, and return to the rule to re–evaluate, and be open to changing the position. I knew I could have that conversation with you in a way that would be frank, personal, but also mindful of the impact of changing a position on something like grammar and how that could be a redirection that leaves a wake in its path.

Were you seeing anything that was making you question it, or did I kind of blindside you?

EH: You really started that ball rolling. I didn’t think about it a great deal. But I think it’s important to note that the other problem with being Black and having skin like this is that it does bestow something weirdly akin to White privilege.

So, look, my racial identity was confusing even among people [who knew me]. I grew up around Alabama Creoles on the Gulf Coast. Black people didn’t know what I was. White people didn’t know what I was. And I spent my whole life confusing people as to “what I am.” And so, over time, I have been impatient with deterministic labels, as I think of them, because I also feel that Americans don’t like ambiguity. And to the extent that I make art through language, one of the axes that that art turns on—and I’m thinking of my poetry and my fiction—one of the axes of that art is ambiguity. But that’s not something that I should be imposing on other people’s art through language.

So, I mean, that really was the simple conclusion there. Once you said, “Well, we should really think about this,” I was like, “Oh, yeah, [that ambiguity thing is] kind of my deal.” But there are a lot of people for whom it’s not ambiguous, and who want the power injected into the word. To me, I said earlier that I wanted to drain the power of it. And I think, again, what I was thinking of draining the power from was the capitalized White.

SH: Yeah.

EH: But as you, on the other side of this equation, pointed out to authors … what comes with that, comes concomitant to that, is the capitalized White when you capitalize Black. Right? It’s all or none. All or none.

SH: Why do you feel like it’s all or none? What’s wrong with the decision, then, to downcase White and uppercase Black?

EH: Here you get into questions of even-handedness. No pun intended, given that I’ve been [lifting] my hand into [camera view]. I very much abide by the dictum: if you identify someone in a text racially, you identify everyone in a text racially. And here, again, I’m thinking primarily of fiction, unless you are working through a point of view, a specific point of view, where that point of view is essentially a bigoted one or a racialized one to the extent that it recognizes only a specific race, if you see what I mean.

SH: Right. It serves only to “other,” rather than …

EH: Right. It serves only to other. And we can’t be othering. That would be a grievous error of bias for the magazine to commit. And I should say, Black people can be wrong too, just in different ways. Right? Like, because I’ve always had this skin, it is possible for me to lose sight of the fact—though it always comes back around to remind me—that no matter what, there will always be people who perceive me one way.

So here are some stories: when I first began doing arts-related journalism, my main communication with gallerists and museum publicists was by phone. And in a handful of cases, when I would finally visit some of those establishments, there would be people [who] would ’fess up to me and say, “You know, we thought you were”—and this was many years ago—“We thought you were a 60-year-old, pot-bellied white man.”

SH: Pot-bellied? [laughs] That’s so specific.

EH: I don’t know. People have told me I sound like Jimmy Stewart. So, the moment people see me, it’s like, “Oh! He’s not what I thought he was at all.” But that’s some people, though it might be most people. I don’t know, because not everyone is going to have that conversation with you. It’s a confession of a certain level or layer of bias. I’d rather hear it than not because it amuses me. The other side of it is not so amusing. So, I don’t know. What I do know is, I’m perfectly capable of getting racial equations wrong. We’re all capable of getting those equations wrong. So, you are well advised, if you are putting out a publication for a general audience, to be on your toes at all times.

SH: Yeah, which goes back to the hesitance [that] I think we both had about solidifying these two terms, Black and White, into such strong binaries—that they become even more entrenched, somehow, when capitalized. There is a kind of implied “this– or that-ness.” And … that still sits uneasily with me. I believe it is the right decision to capitalize these terms, because, from whatever direction you’re looking at them—as a positive or negative, through bias or through empowerment—they carry a weight that warrants capitalization. If a word has enough baggage, it should just achieve capitalization, perhaps. But it does sit uneasily, how that capitalization might do damage to a nuance that I always want to allow room for, a nonbinary nuance. A refusal of legibility that I think is really important, especially when writing about art.

But as it happened, we set out to do this issue that looked at art engaged with [a] civil rights context, primarily in the US, post–2012. As that issue started to approach, I really felt an uncomfortability with downcasing … that this was the moment to re–evaluate that rule. And so, you’ll see in the issue that Black and White are capitalized, for better or for worse. And, you know, the flipside was that it meant, at times, capitalizing Black as an editor, when writers had not capitalized it in their own drafts. I mean, these are bolder moves than I often feel comfortable making.

EH: I believe you usually refer to them as authorial. “That was a very authorial decision there. Very authorial choice!”

SH: Yeah! And I avoid those. I would much rather have a conversation than make an authorial decision within someone else’s authorship.

EH: Me, too. And yet, every now and then I will make them sometimes—or I should say, I will suggest them sometimes, because I feel that you’re looking at a potentially missed opportunity. Things like, what I call the Ellisonian paragraph—and this is Harlan Ellison, not Ralph Ellison. I think I made this change a time or two on your watch, where I’ve come back and said, “The last sentence of this needs to be a paragraph of its own,” which is a very authorial change to make.

SH: I think this goes back to the question of having a style guide at all. You know, the style guide becomes a way of pre–empting, standardizing, and justifying those things that fall outside of [the Chicago Manual of Style’s] scope (because we basically default to Chicago)—where we choose to deviate, or if we want to lean into more detail on a particular issue that comes up frequently, or something like that. And yet—and this is something that I appreciate about your style as a copy editor, and that I hope never changes—we still kind of go case by case. The style guide is a living document, as we learned when we were working with guest editor Emily Watlington on a transformative issue with the theme of Disability and the Politics of Visibility.

EH: It’s a great issue.

SH: It’s a great issue. It was something I had not seen done in arts publishing in the way that … issue was done. And it really presented an opportunity for us to re–evaluate how we were dealing with language around ability and access. These are decisions that ultimately impact the character and position and ideological underpinning of a publication. I feel like, once I started seeing the style guide in that way, it became a much more interesting document to me—not that it wasn’t interesting before!

EH: You wound me! [laughter] It has always been a very personal document for me, from the get-go.

SH: I definitely hear your voice in our style guide.

EH: As you should! But you also hear, for example, Nicola Griffith’s voice. Our entry on why we do not use the term lame as a dismissive is directly the fruit of her wonderful essay—if you haven’t read it, go read it—“Lame Is So Gay.”

So, yeah, we proscribe that word [in any pejorative sense], and I will square-bracket it out of any interview in which it appears. Disallowed! And if you’re … in journalism and [still] using that word on air—NPR!—cut it out!

Emily Watlington’s issue brought up things that I had not thought about: on the other hand! Right? That’s an ableist metaphor. Not everyone has an other hand. Or any hand ….

SH: To go back and explain myself …. What I mean about the style guide becoming more interesting—I think that now I see it as this space where you and I, and whatever other collaborators and influences we want to bring in, really determine who we are as a publication. It’s not just rules for good style or how we capitalize certain things or punctuate certain things in a kind of rote, informational way. It’s a space where we can hash out what our investments are. Where we want to deviate from the rules. And where we can question rules, not only their efficacy but their underpinnings. So, it becomes a space of interrogation, which is always much more interesting to me than a list of rules. Right?

EH: Yeah.

SH: Well, so, do you have any closing statements that you feel like we should make sure we get in here?

EH: I know that you had been struck by the passing of Maurice Berger.

….

There’s something in the appreciation that you sent to me, written about him. What was the author’s name again?

SH: Aruna D’Souza.

EH: That one, yes. Where he’s quoted as saying, in doing the kind of things that he did, there was a lot of, I think, grief and consternation to it. But also rewards. And I’d like to think that that applies to the enterprise of the style guide, too. And that’s mainly why I bring it up. That can be fraught. It can seem, perhaps to outsiders, arbitrary, but I think it is worth it to question these presumptions and assumptions … and, yeah, there are rewards in wording things to not wound people.

SH: Yes. If there is an opportunity in a decision you make to uplift versus to wound, that choice is a pretty simple one.

EH: I was going to say, that’s no decision at all.

SH: Right, and it’s worth re–evaluating your positions all the time, in response to the opportunity to make that choice correctly.

EH: Agreed.

***

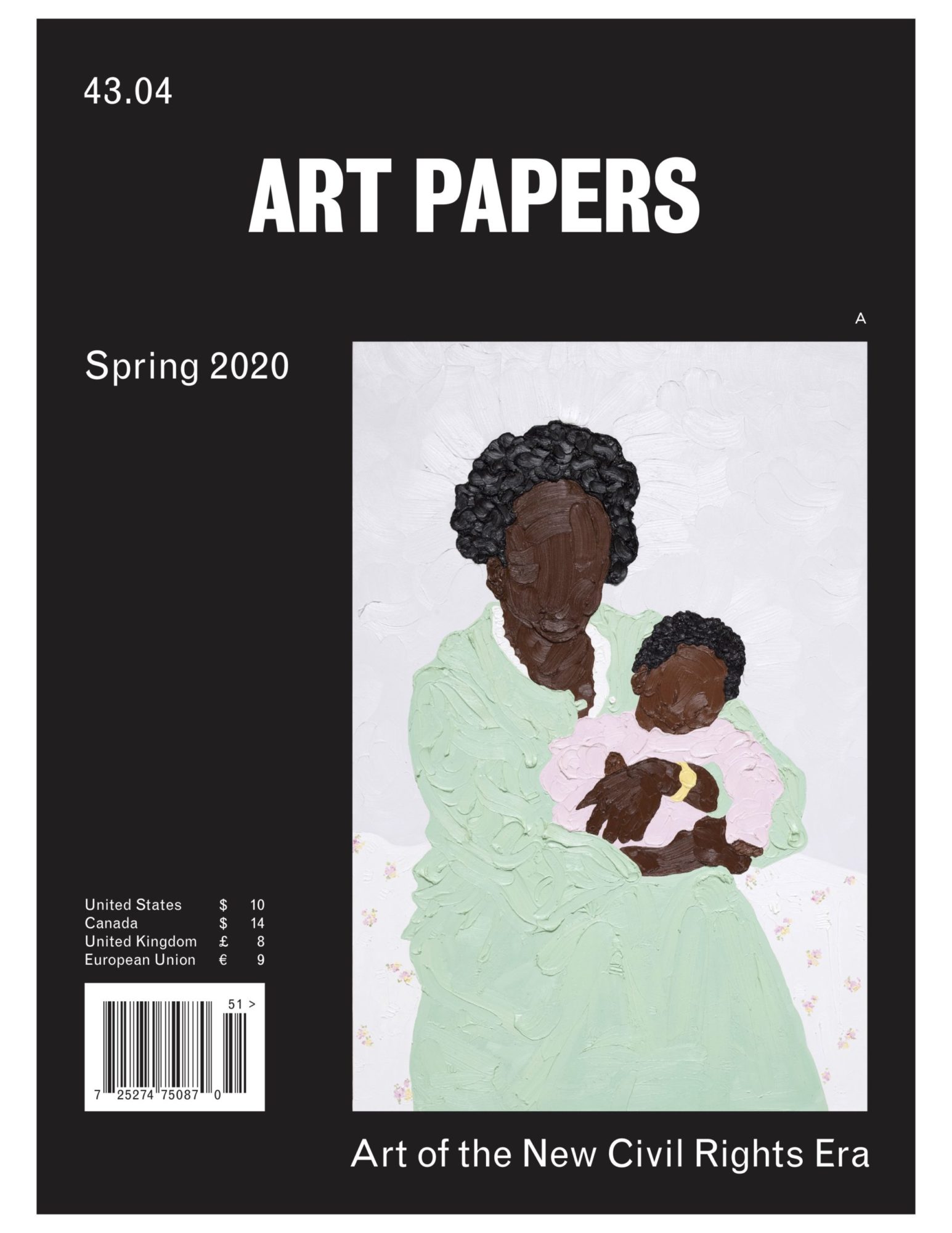

This interview was produced in conjunction with ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.

Sarah Higgins is the Editor + Artistic Director of Art Papers. Previously, she was curator at the Zuckerman Museum of Art at Kennesaw State University from 2015-2018. There, she produced catalogs and exhibitions including Gut Feelings, Tomashi Jackson: Interstate Love Song, and A View Beyond the Trees. She has curated over 40 exhibitions featuring a diverse range of emerging, established, and international artists for institutions such as the Hessel Museum of Art, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, and Atlantic Center for the Arts.

Ed Hall, with ART PAPERS since January 2013, writes journalism, poetry, and fiction. He created Attend, the original calendar of arts events for artsatl.com, and he has been a regular contributor to burnaway.org. He served the nonprofit Eyedrum Art and Music Gallery as host of its monthly literary forum, Writers Exchange; as an organizer of Eyedrum’s annual eXperimental Writer Asylum; and as a board member and officer for almost a decade. His work has appeared in Newsweek and Code Z: Black Visual Culture Now. He wrote the Dictionary of Literary Biography entry on cartoonist Alison Bechdel. Hall co-edited ART PAPERS’ 2017 special issue on author Philip K. Dick, as well as Rosarium Publishing’s 2013 anthology Mothership: Tales From Afrofuturism and Beyond, which The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction suggested might be “one of the most important sf anthologies of the decade.”

References

| ↑1 | Because I also copy edited this interview, I determined after the fact that the phrase Black Is Beautiful, as the name of a movement, has each of its words capitalized, please note. EH |

|---|