Disability and the Politics of Visibility

Share:

In my first year of art school, I made my process-oriented drawing class  navigate our campus at my slow pace and via the convoluted routes I had developed in order to avoid stairs. I was introduced to artistic practice around the same time chronic Lyme disease was introduced to my body (or, at least, around the time I received my late-stage diagnosis). My pain from Lyme arthritis is invisible, and inconsistent, and I was growing increasingly frustrated by the disgruntled glares I received from strangers in my school’s elevator when I took it only one floor. They were signaling to me that I was slowing them down, and that I was lazy: not knowing, because it’s not visible, that stairs weren’t an option. I was asking my classmates to not assume.

navigate our campus at my slow pace and via the convoluted routes I had developed in order to avoid stairs. I was introduced to artistic practice around the same time chronic Lyme disease was introduced to my body (or, at least, around the time I received my late-stage diagnosis). My pain from Lyme arthritis is invisible, and inconsistent, and I was growing increasingly frustrated by the disgruntled glares I received from strangers in my school’s elevator when I took it only one floor. They were signaling to me that I was slowing them down, and that I was lazy: not knowing, because it’s not visible, that stairs weren’t an option. I was asking my classmates to not assume.

I wouldn’t learn much about disability politics and community until years later. But from experience, I was aware that visibility (and therefore art) is deeply entangled with experiences of disability and chronic illness. But as society has demanded that the disabled and chronically ill render their experiences visible, efforts have often veered toward hypervisibility in the form of abusive representations that make a spectacle of “otherness,” inheriting tropes from the freak show. There’s a troubling flipside, too: the underrepresentation of disabled people in popular culture and positions of power. There’s also some work to do regarding the medium of visual art: a field whose opto-centrism often perpetuates exclusion, continually assuming only sighted and hearing audiences.

Numerous artists have been making thoughtful and urgent work about disability and its politics, but quite a few confided in me that they felt the curators and art writers who framed and mediated the artists’ work were frequently unaware of, or insensitive to, what is often understood as common courtesy in the disability community. They might inadvertently describe work using ableist language or refuse to provide additional funds for ASL interpreters or accessible hotel rooms, placing these extra costs on the artist and thereby exacerbating the barriers disabled artists face. Lack of accommodation is often present in exhibition design, too, such as when videos lack closed captions, strobe warnings are absent or included as ineffective afterthoughts, or websites fail to mention whether an event or space is wheelchair accessible. This lack of consideration is not a problem unique to the art world; the disabled are regularly underrepresented even within diversity initiatives, which have privileged other prescient issues related to race, gender, class, and sexuality.

In hopes of equipping the art community with an introductory disability discourse—and thereby tools for more mindful future art, writing, exhibitions, and programs—this issue highlights a small selection of artists, architects, and writers working today who are concerned with disability and the politics of visibility. A glossary by Ann Millet-Gallant kicks off the issue and introduces some basic terms and concepts from disability studies that recur in its pages.

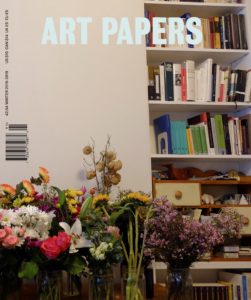

Perhaps the most beautiful thing that disability makes visible is the presence and importance of interdependence and care networks, which are often erased in an art world that continues to privilege autonomous authors, and in a society where care work is undervalued and backgrounded. This dynamic is present throughout the issue, and also captured by its cover: Carolyn Lazard’s Support System (For Park, Tina, and Bob) (2016), which documents the artist’s 12-hour performance, during which they spent the day in bed. Visitors were invited for 30 minute slots, and the cost of admission was a bouquet of flowers. The collection of bouquets represents Lazard’s care network, and those who showed up to see them while the artist lay sick in bed—a quite intimate state we tend to make visible to only a select few in our lives, as we opt instead to present ourselves only at what society tends to consider our best. Many of the bouquets were brought to Lazard by contributors to this issue, who care about, support, and collaborate with one another, refuting any hierarchy between art work and care work. In this spirit, I’m extremely grateful to the artists, contributors, and the Art Papers team, as well as to the students and guests for my course last fall at MIT, “Architectural Access: Code and Care,” which I co-taught with Gabriel Cira. He also designed this issue. I feel very fortunate to have worked with and learned from them all, and to be able to share a sliver of the thoughtful work being done, all of which makes pointed demands for the future of accessible art.

Emily Watlington

Guest Editor