Kelly Taylor Mitchell: Masking Practice

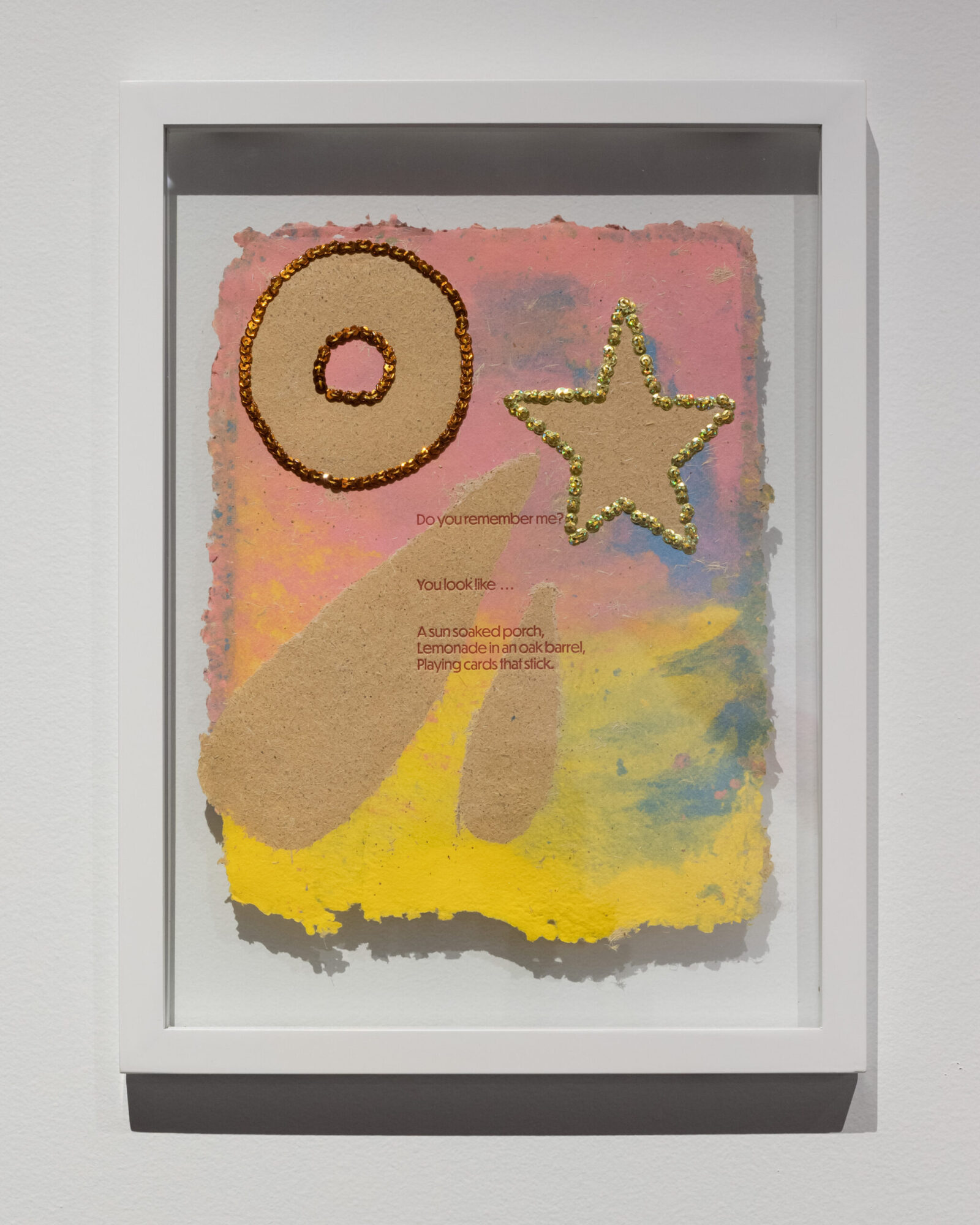

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Between Starshine & Clay, installation view, 2021, unbound artist book, original text, artist made cotton and kudzu paper, hand embroidery, screen printing, and letterpress, 11 x 15 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

Share:

Kelly Taylor Mitchell is a performance artist, but you’ll never see her perform. Instead, the experience of her work is like that of a memory: elusive, fragmented, felt through material, symbol, and sense; full of joy, laughter, and sweet aching for what came to pass. Her mixed media works are part performance documentation, part altar, part formal engagement with the archival. More than a weaver of spiritual and sensorial remembrance, Mitchell is a historian of her own familial intersections with the long-suppressed histories of marronage in the American South. Mitchell specifically explores her own ancestral connections to the Great Dismal Swamp, one such site of marronage that once covered more than a million acres, overlapping parts of Virginia and North Carolina, where unceded Nansemond, Chesapeake, WiYaPeMiAk (Weapemeoc-Yeopim), and Lumbee lands converge. Her multidisciplinary work, rooted as deeply in ritual as it is in material history, conveys a longing to connect, communicate, and celebrate the entanglement of personal and cultural histories.

Sarah Higgins: I think of your work as having two modes. There is a performance side of your practice that’s very private. It’s about ritual. It relates to ancestry and being with your ancestors or your immediate family. And then, there’s the documentation object-making, the material practice. And I wanted to just ask you to characterize your practice with a mind to those two polarities within it.

Kelly Taylor Mitchell: It’s interesting to hear them described as separate entities, because one can’t exist without the other for me, and they feed each other. I was talking with my partner about this idea of the ouroboros … that Egyptian snake that’s always eating its tail, and that feels like a good image of what happens in my practice. A lot of the object-based work has utilitarian function. It’s not unusual to hear me talk about a term that I was introduced to through Christopher Franklin, “spiritual technologies,” when thinking about my work. And so especially with textile–based objects, seeing them as having a utilitarian spiritual function. Usually that utility is happening inside a performance or ritual ceremony. I sort of use those words interchangeably. The performances, which as you mentioned are private—I document them, and then they feed more objects. Their documentations become adornments for these objects. And so, the cycle continues.

SH: The objects that you’re making here in your studio, are they all made for inclusion in your performances? Do they each take their turn in the ritual aspect of your practice, or are some of them coming out of, but not feeding back into, the loop?

KTM: I love that description, coming out of, because I think of a lot of the handmade paper works almost as abstractions of utilitarian objects. I was thinking a lot about how these objects that have an incredibly personal and private function, and then they go in a gallery space or museum space and that function is removed. But [the function] still has sites of legibility, whether it’s through materials, or these fragments of images, or other adornments that are incredibly familiar and can trigger memory for people.

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Mask #7, 2021, hand embroidered and beaded mask [courtesy of the artist]

I want to think about how I can make works that speak to a lot of reference points, especially in these textile pieces that I’m calling the spiritual technologies. And these works are really invested in histories of masquerade that we see across the Africana diaspora, which all have these non-homogenous, but certainly interconnected, ties to practices of ancestor worship, and of embodiment. I was thinking a lot about talisman—Afro-Brazilian mandingas, and amulets, these sort of objects that we build and create to serve us or protect us or yield some sort of good.

I want to create work that still speaks about history but doesn’t have the functional aspect. So, these textile pieces are existing inside of that lineage, and can exist because of that lineage. They’re also not trying to replicate it. I’m trying to—very much like a quilt—take these little different pieces and patch them together to make my own blocks, so to speak, of this ancestor worship–based practice. And then, the handmade paper pieces feel like an abstraction, because they don’t have that utility, that usability. I don’t engage with it with my body in a performative way—in private or otherwise. They live on the wall.

I do think there is still a performative element in the act of making paper, the foraging of materials. The histories and stories of the materials themselves carry the actual raw fiber plant life that you turn into pulp, that you turn into paper. And then the act of making, standing behind this vat full of water, which is the most incredible material. And you have this wet pulp, and you’re pulling it, and you’re creating it or turning it into this new form. It feels very performative.

SH: Relating back to what you were saying about memory—there’s a filtering, a sifting, in reaching into the vat and pulling something to the surface. And then the thing coalesces. Do you think of memory as being something that can be shared through materials? Can a memory that is your own, or a memory that is someone else’s—unrelated and yet related—be shared through materials? How do memory and material work together as communication tools in your work?

KTM: A few things are coming to mind. One being, yes, of course I think memory can be translated through material, absolutely. Do I think that the memory that I have attached to this material is a memory that you’re going to have attached to this material? Probably not. Or maybe yes, but to me that’s the beauty of that communication. Something that I think is really exciting about what happens in my work is where we can find each other along that pathway. Something else that comes to mind—someone I talk about frequently in my work is Toni Morrison, and her idea of rememory—this idea of recalling the forgotten that she talks about in Beloved, with her character Sethe.

And so, yes, I also think you can meditate on, contribute to, be in conversation with—maybe that’s my favorite one. I think that’s my preference with someone else’s memory. And so, for me that looks a lot like thinking about how speculative frameworks would look. And I think my work is really interested in the archive—my personal family archive, specifically. And for me, those archives have a lot of question marks and gaps and, quote unquote, “missing information.” And I’ve really enjoyed being more comfortable shifting the narrative from “missing information” to an opportunity—for me to create a narrative from the seedlings that I have. So how can I take the information that I have and plant that to grow and foster a new thing?

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Between Starshine & Clay, installation detail, 2021, unbound artist book, original text, artist made cotton and kudzu paper, hand embroidery, screen printing, and letterpress, 11 x 15 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

Materials can help you do that in a variety of different ways. I just brought back these materials from Bahia. I went for a fellowship to Bahia, and I brought back this white cotton that’s typically used for setting your altar. And I was thinking about altar spaces that I keep in my home and the things I utilize to call people in. And then I also started to think, “What does that calling in look like in my daily life, in practice outside of this intentional space of an altar?”

I started to think about language, and these phrases and sayings that are passed on, that come up every day, every week. I’ve been sort of jotting down different phrases that I’m going to use for this piece, this series of works where those phrases are embedded in these ultra-setting pieces with other adornments, and so on and so forth. But that’s just an example of taking the original context of a material and how it can maybe exist in a similar sphere that’s also not, again, not a re–creation, but your own interpretation of how it can function.

SH: Through an association with an established context and meaning?

KTM: Exactly.

SH: What about the images in your work—where they’re coming from, and the process of deconstruction and reconstruction that happens with them?

KTM: So, images in the work tend to come from two places. One being my grandfather’s archive. I was really, really close to my grandfather [while I was] growing up. He was very much the family historian, and he grew up in North Carolina and would travel back there frequently. And we spent a lot of time in his backyard garden in Pennsylvania, together, where I grew up. And I had no idea that he was a photographer. And when he passed away, my grandmother offered me these bankers’ boxes full of all sorts of things, one of which was slides and his Kodak carousel slide projector. And I learned this new part of him, this memory keeper [whom] I didn’t know. And he kind of stopped—he seemed to stop taking photos after my sister was born. There are a few of her as an infant. And that seems to be the end of that documentation.

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Brown is My Favorite Color (work in progress), 2021, found Battenburg tablecloths, dying, hand embroidery, heat image transfer, 175 x 65 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

And those images are so central to my practice, but I still haven’t quite figured out how to utilize them. Sometimes they’re present in some of these textile works, but that’s become more infrequent. Sometimes, if I have an open studio, I’ll play my slide projector when I’m in my studio by myself. Certainly, I love to, thinking about, again … this idea of calling people in, of calling people in, quite literally, by having their image slide across my wall is a gift. It is really special. But I also am very aware that most of the people in these images aren’t here and can’t consent to be in the work maybe in the way that I would like.

And then also trying to balance that with the permission that was granted [for] giving these to me, of these being given to me by my grandmother. And so, there’s one piece that’s not on the wall right now, that was in the MOCA GA show, that I call my forever work in progress. And that’s the primary piece where you see those archival family images. And so, I really wanted to think about how I can offer these pieces protection, which is a big part of how I think about this work. I’m saying it has this utilitarian spiritual capacity, but then it’s existing in spaces where it’s not being utilized in that way, where it’s encountering people who it’s not made for. I don’t have the spiritual capacity to make these sorts of objects for other people and would never claim to. And so, I’m really aware of how I want to protect the work for my sake, for the sake of the work, and then most importantly, when it comes to images, for the sake of the people in the images.

SH: There’s a negotiation between what can be accessed, what you can access, but the viewer can’t, what the viewer can access, but you can’t. And that speaks to what you were saying about memory, but it’s also in what you were just saying about the transition from a ritual object to something that enters a space of different criteria, and of different expectations for what the work is presumed to be and called upon to do.

KTM: Exactly.

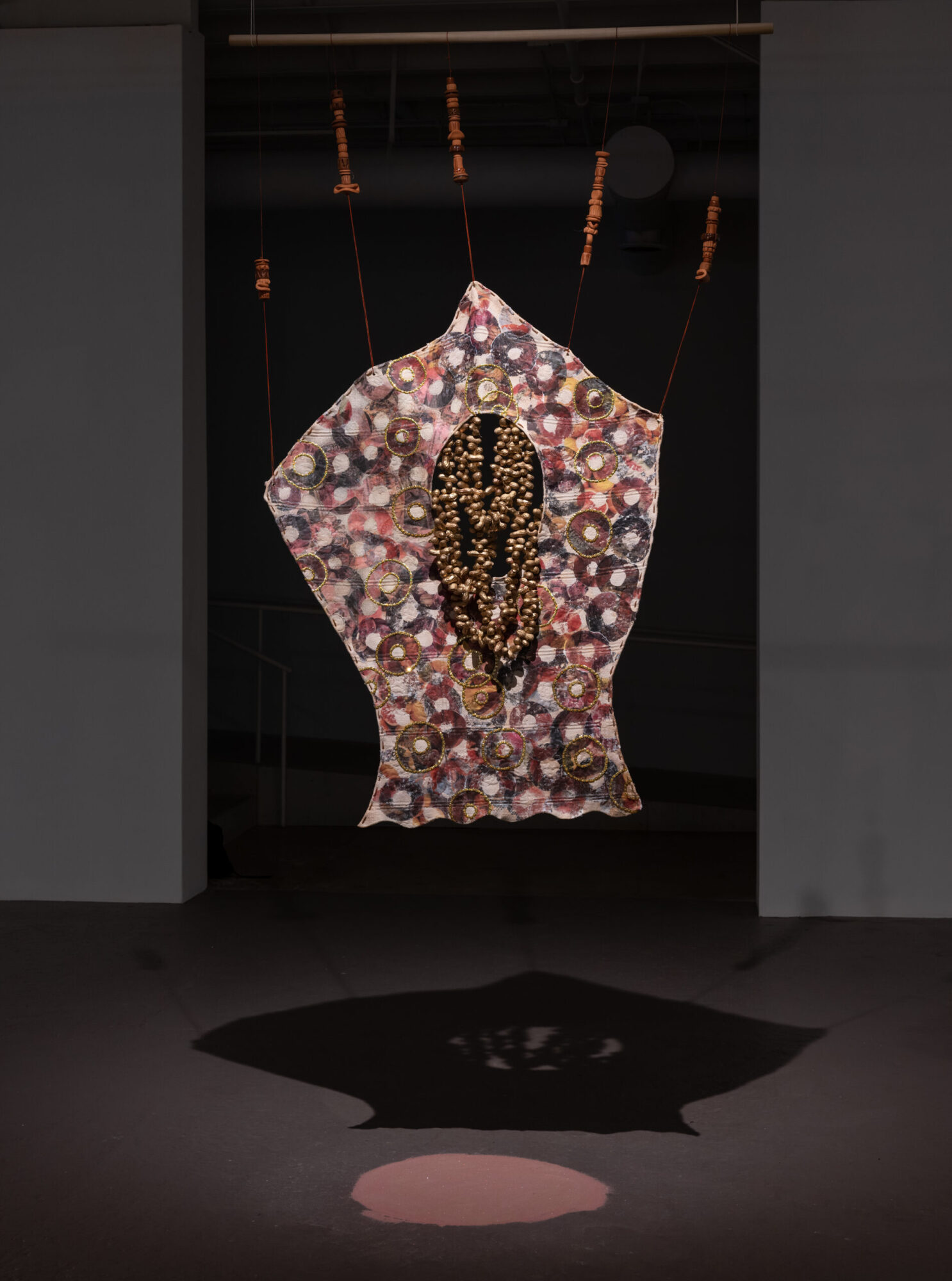

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Totem #2, 2021, dyed textiles, costume pearls, popcorn gel medium transfers of images from the Great Dismal Swamp, hand embroidery, ceramic beads, 102 x 32 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

SH: And we’ve talked before about some of the ways that you negotiate that in terms of how you bring the things into the space. And I’d be so interested to hear more about that in terms of how you prepare to protect—the steps you take to protect the work. And also, just in doing what we’re doing right now, in talking about the work. What you disclose, and what you choose not to disclose, and where you draw those lines and why.

KTM: In terms of bringing the work into spaces where we have this new possibility as it relates to the function of the work, or maybe new limitation is another way to think about it, too. Or boundary, maybe, is a more generous word; new boundaries for what the work can do. Again, I’m thinking about these spiritual technology textile pieces, and one thing that I have been doing is laying down what I call brick dust. It’s not brick dust, but it’s referential to brick dust. And I lay it in a pile underneath the work, but it usually extends, it’s a circle. So, we’re in the round and it usually extends out so that if you got any closer than, I don’t know, a foot, you’d be stepping in this pile, which is also incredibly pigmented. It will track everywhere. So that evidence of that, there’s different ways to think about it. The evidence of the, one could say, invasion.

SH: Yeah, I was thinking encroachment.

KTM: Encroachment, right. Or comfort. I also try to have some grace, which is a word we were talking about earlier, when thinking about that proximity that can happen. And that is sort of evidenced through this pile of brick dust. For one person it could be this encroachment, and for someone else it could be this call, right? A pull to this thing.

SH: Yeah, a mark of intimacy.

KTM: Exactly. But either way, I see that as a protective tool. And the reason I bring up brick dust is because that is a practice of marking your thresholds or the exterior—well, in the interior of your house, but those exterior walls with this brick dust to sort of keep out energy, spirits, people who mean you harm. It’s an effort to offer that to the world. And then similarly, when the work is then returned to the studio trying to offer it space to sort of rest and recover, just like I try to offer that to myself when I’ve been out in the world for a long time.

And when I think about disclosure, I think about this anecdote when I was doing an artist talk and I was talking about this idea of private performance and how, going back to one of your other questions, this other arena that the images in my work come from are … these ritual ceremonies or private performances that typically happen either in my studio space or in the Great Dismal Swamp, which is this really central site in my research, in my family’s story, in my practice. Or these other sort of charged sites that are in that universe, in the work or the mythology that’s sort of being built within the work.

SH: Can you say more about the Great Dismal Swamp?

KTM: I can, oh my goodness. One of my favorite things to talk about. So, the Great Dismal Swamp is a swampland, a very large, vast swampland that straddles—actually, I’m sorry, I’m straddling the heater. I’m seeing you getting cold and I’m, like—

SH: —Oh, I’ll scoot in. We can share it.

KTM: Our little campfire.

It straddles North Carolina and Virginia, and it is the largest known site of marronage in the United States. And anywhere you have histories of enslavement, you are going to see histories of marronage. So typically, that’s going to mean formerly enslaved and indigenous populations banding together to build autonomous community. And sometimes that autonomy is engaging with the larger population in different ways—economically, socially—and sometimes it’s totally separate. The Great Dismal Swamp was an example … a site where they were engaging economically with the larger population. There was a logging industry that the maroons were facilitating.

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Untitled (Green), 2021, artist made pigmented cotton paper, grommets, mesh, chandelier crystals, 86 x 44 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

And you’ll also see—it’s fascinating but not surprising at all—that the histories of the swamp aren’t recorded in ways that reflect the depth and richness of this incredible community, or even at all. Most of the history you see is about George Washington, who tried to drain the swamp and turn it into a plantation.

SH: Is he the one that named it the Great Dismal Swamp?

KTM: That’s a good question. I actually don’t know.

SH: Because it’s a hell of a name.

KTM: It’s a hell of a name. It’s a hell of a name. But I don’t think that it can be credited to George Washington. But it’s worth looking into.

My ancestors, who were enslaved in North Carolina, found themselves in the swamp. I know the details of how they found themselves there, and that they eventually left. And what fascinates me, too, in terms of what is not centered, and how we tell the history of that site, are the threads we see across other sites of marronage. Around the diaspora, entrenched African religious traditions—which is a huge umbrella term, to be clear—but African religious traditions permeate those communities.

And central to the majority of these traditions is some type of ancestor worship practice. That is churning and circling around these questions, and [is] a big part of building that practice for myself, here, in this work. The work almost started as me trying to envision what that looked like, and then realizing that, oh, I’m just doing the thing. I was trying to envision what an ancestor worship practice looked like in this place, for my ancestors, and then realized that I was just creating my own iteration of an ancestor worship practice that was informed by that envisioning, as opposed to just trying to reflect, which was a really exciting realization.

I think, when it comes to this idea of disclosure, I find that this private performance element is a place where people really want me to say more. And I think back to that artist talk where I was talking about this idea of private performance, and I really, really value the limited opportunities that I’ve had to do this in the swamp, where I’ll bring these masks, these hand–embroidered and beaded masks. I wear them, and then there’s this ritual ceremony that happens in these sites, these sites that, again, [are] documented and then … fed back into the work in different ways. And I was talking about how important that privacy is to me. And someone said, “Well, can you do the performance for us here, right now?” No.

SH: Of course not!

KTM: Of course not. And so, there are definitely times when what I want to disclose and don’t want to disclose becomes really present in the work.

SH: Yeah, there’s something so powerful in choosing opacity, even in just a very matter–of–fact way. And not necessarily in the Glissantean sense, although opacity is in the work in that sense, too—the choice to not reveal something from a deep history that was already subject to extraction, appropriation—

KTM: —Absolutely.

SH: And to a form of erasure that was an act of violence. To offer up your own conjuring of that history to those same violences would be, I don’t know, just deeply unthoughtful.

But then there’s also the thing where we demand this of art and artists. We often feel entitled to the explanation, to the process, to the reveal.

I know that you are an art professor at Spelman, and I was curious how you—or if you—encounter these conversations with student artists who are forming their practice and possibly questioning these same things about what you make for a viewer and what you make for yourself, and how you negotiate the desire to communicate or commune with a viewer, with the need to protect yourself, because “the viewer” is a big umbrella.

KTM: Absolutely. I mean, as you were posing this question and reflecting on these ideas, I was thinking a lot about the limitations of the word resilience, which feels [pauses]

SH: Almost spiteful?

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Totem #1, 2021, dyed textiles, peanuts, gel medium transfers of images from the Great Dismal Swamp, hand embroidery, ceramic beads, 63 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist and MOCA GA, Atlanta]

KTM: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And then, hearing you bring up my students, I was thinking about how—and this is a conversation that I have a lot, I’ve had a lot with my mom when I was a student, and have a lot now with one of my incredible colleagues, a photographer, Nydia Blas—your work is allowed to be joyous. Making can be fun. How would your work shift and change if you centered those things in your practice? When I think about that person in the audience who asked me to perform here, right now, what I do in private performance—I think there are a lot of people for whom it’s easier when art is about just one thing. Which I don’t think art is ever about, one thing.

SH: Not the good stuff.

KTM: No, not the good stuff. And I think a lot of people, especially when you’re talking about Black artists, want our work to be about trauma, about enslavement, about suffering, about resilience. And it’s like, that’s just one part of the puzzle.

I think it’s important always for me to remind people, and to remind myself, and maybe at the top of that list, to remind my students, that for me, this is celebratory. The reality of deep history and looking back doesn’t negate that at all. Not at all.

SH: Yes, your work feels invested in the past in a way that argues … it’s not a betrayal of those hard things to find the joy in the history. I mean, on the contrary, it’s different from resilience, and a nuanced difference, maybe. But it’s less in spite of and more untouchable by.

KTM: Absolutely. And I think, too, asking yourself, what does that joy and celebration look like? For me, in the work, a lot of it looks like slowness. My work is incredibly labor intensive. That’s on purpose. I’ve been imbuing this work with a very real–to–me power, and an ability to make space for ancestral connection. Offering embodiment requires building intimacy, which, for me, requires time. And, for me, it requires utilizing methods and ways of working that were passed down to me. Many people—again, thinking about memory and these things that are shared, even though they may diverge—many people can talk about how their grandmother taught them to sew. Right? That’s a beautiful, I think …

SH: Shared experience?

KTM: Shared experience. Yeah, so I like to think about the ways process intersects with this conversation. And it’s also something I encourage my students to think about.

Kelly Taylor Mitchell, Mask #11, 2022, hand embroidered and beaded mask [courtesy of the artist]

SH: You mentioned the masks that are part of your practice. There are so many things, depending on the masking traditions you’re drawing from, so many varied histories, symbolic meanings. Could you talk about how the masks are, and relate to, your work?

KTM: Yeah. I think about the masks as step one, in a way. I think also about the masks as probably the primary site of this idea of ancestral connection, as opposed to just an offering. That comes from the act of wearing, and is most present with the masks. With the textile objects, I engage them with my body, physically, this idea of moving and gesturing and et cetera. But the masks I put on.

SH: And that’s part of a performance that you’re doing for yourself, or for the not physically present.

KTM: Exactly.

SH: I often think of a mask as being for the viewer—a way of transforming one’s body for those who look upon it, or of hiding the body, or hiding the face—changing your identity or muting it. But for that interpretation there’s always an implied viewer. It’s interesting that, with your masks, it’s an interior experience. They’re an inversion of the process of masking that I’m accustomed to seeing evoked, especially in art spaces.

KTM: I think it depends on the context from which you encounter masks and find the most commonly evoked. If we look into the diaspora, this is a very standard practice: utilizing masks as a tool, whether it’s for ancestral connection or embodiment or celebration or reverence. You will see this practice, again, in different forms, in different iterations. But the idea of putting on, of coverage, of masking.

SH: So, by doing the action, you enter another place? Or you enter in a different embodiment?

KTM: Exactly. And again, there’s the idea of labor. I think it’s really present here. These probably take me the longest to work with. They’re the works that, I wouldn’t say I struggle most with, but that I sort of question the most. How do I want to share them? When it comes to the documentation of them, that’s why, when I embed the performance images into the textile pieces, usually the masks are often somewhat obscured. But again, this act of protection is a sort of privacy—withholding, maybe, a little bit, too. Boundaries are present in how they’re shared, and in all sorts of ways, whether it’s the documentation or the physical thing.

SH: Yeah. It’s funny, folks often talk about setting healthy boundaries, y’know, just out in the world, between people. I think maybe that’s underutilized, or not often carried into the discourse around art making—setting intentional boundaries.

KTM: And that’s definitely a conversation with students, right?

SH: Yeah, if you can understand the need for, the benefit of, but also the challenges of setting healthy boundaries, and protecting them, how do you then bring all of that into the work? And in a funny way, maybe let those boundaries for the work support you, in return.

KTM: Absolutely. I think the reason I thought about my students is, it feels like a really serious gift and very big responsibility to be able to teach these incredibly engaged and present artists. You can say no. Right? You can set boundaries, you can identify your values, which are allowed to be malleable and shift, but you can identify values and then make decisions that reflect them.

That doesn’t mean it will always be easy or that that it may not have consequences that feel disappointing, or that maybe sometimes you won’t be able to do that, for whatever reason. But you can have boundaries in your practice. And I think, especially as young Black artists—it makes me think about what you were saying about extortion. It feels important to try to shift that dynamic, and it’s obviously a systemic problem that requires some systemic solutions, but I think as individual artists, we can try to insert boundaries as one offering.

Sarah Higgins is editor + artistic director of Art Papers.