On Biodiversity—Timur Si-Qin and Haley Mellin in Conversation

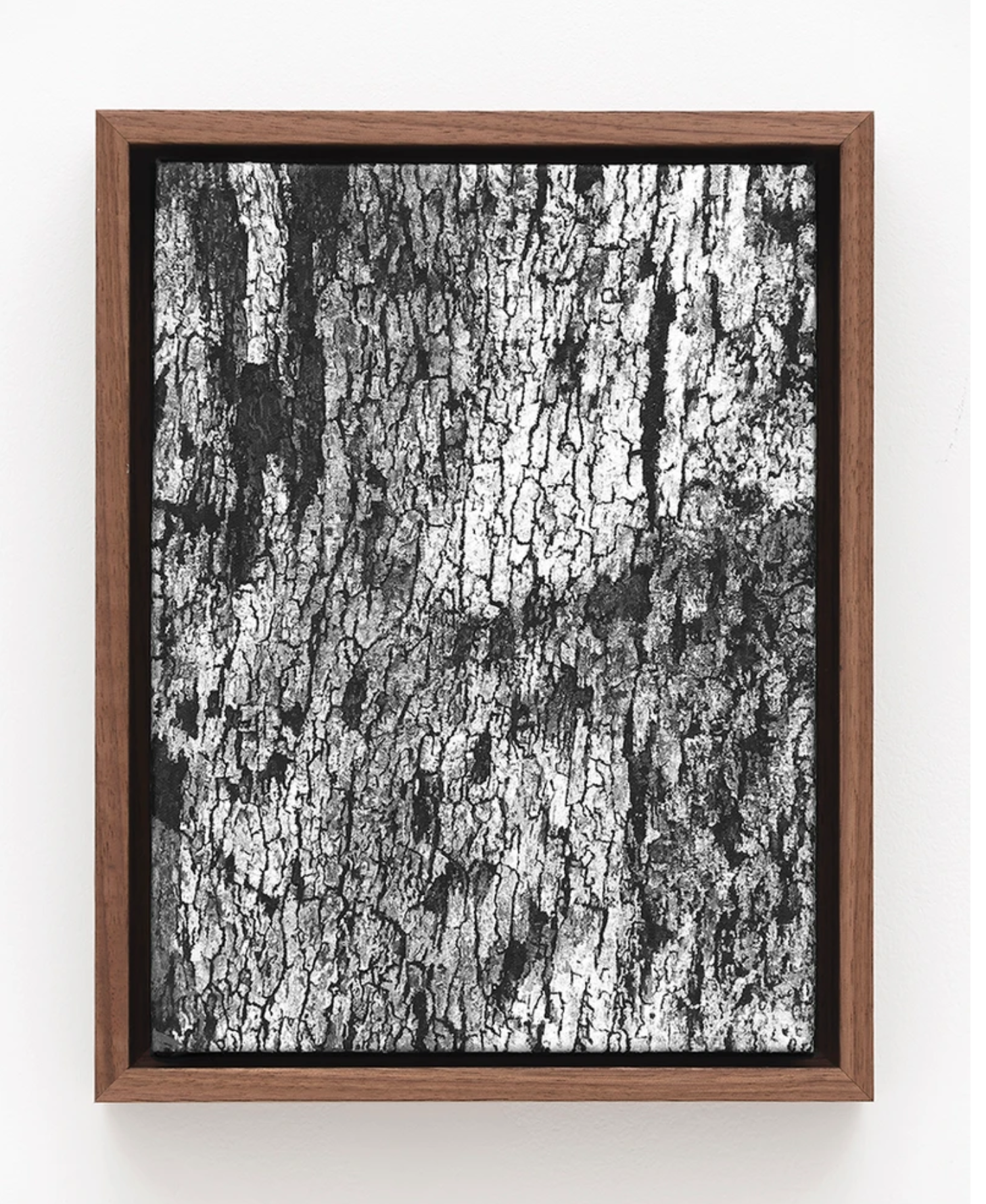

Left: Haley Mellin, CT 15.4646°N, 90.7794°W, 2022, Gouache on canvas in artist frame, 12.75 x 10 in. [courtesy of Thomas Mueller and The Journal Gallery]

Right: Timur Si- Qin, Tree of Deciduous Being, 2024, bronze [courtesy of artist and Magician Space Beijing]

Share:

Timur Si-Qin: Through the nonprofit Art into Acres, you’ve engaged artists and institutions to raise funds and attention toward large-scale land conservation efforts. In my eyes, you’re one of the rare artists who have been able to use their art for a greater purpose—the preservation of our natural world. Today we are in a critical phase, one in which we only have a few years left to prevent the worst outcomes of climate change and biodiversity loss.

With a team of scientists and biologists, you’re co-authoring an upcoming paper titled “Conservation Imperatives,” which identifies the critical places on Earth to protect, within the next five years, to prevent the most likely imminent extinctions. Incredibly, the paper identifies that preserving an additional 1.2 percent of the earth’s surface would stave off the sixth major extinction. Can you tell me about the paper?

Haley Mellin: The paper focuses on a global mapping of rare, threatened, and endemic species not currently under adequate protection. It will be published later this year in Frontiers, a Swiss publisher of themed journals, and was a widely collaborative effort. This mapping was the first time I could see, in detail, pixel by pixel, where the evolution of biodiverse life has occurred—small valleys or mountaintops—as biodiversity is not spread equally on Earth but exists, instead, in pockets.

The map proposes the expanded habitat protection of 164 million hectares, or 1.22 percent of the earth’s land surface, where biodiversity and betadiversity are high. Multiple pathways can lead to this—including providing rights and titles to Indigenous peoples and local communities, municipal and local-government creation of new protected areas, or the purchase and leasing of private lands.

Art into Acres webpage [screenshot courtesy AiA]

TSQ: How was the Conservation Imperatives paper first initiated?

HM: In June 2022, I was meeting with a group of conservation biologists, scientists, satellite specialists, and activists and asked, What lands should be conserved to protect the habitat of 80% or more of known species? The paper will be a presentation, which follows from that conversation, and will, for the first time, show detailed mapping of this answer.

Currently, the scientific community thinks there are about 8.7 million species on Earth, of which we are one. For example, insects and mammals have been largely described, but there are quite a lot of unknown plant species. At present, if only about one in eight of these are described by science, then most of the earth’s species remain a mystery to us.

TSQ: Can you talk about how you will use Conservation Imperatives, and the potential impacts this paper can have?

HM: A healthy way for long-term habitat protection to unfold is through community-led, Indigenous-led, and locally led engagements, where the people who live within—or near—an ecosystem steward its long-term protection. Overall, the Conservation Imperatives mapping research can support wildlands protection advocacy by the public, and by local and national governments, while also being a resource for local and Indigenous communities who are requesting land protection.

In terms of concrete action, after the paper entered peer-review mode, Art into Acres made a grant in November 2023 to RESOLVE. The grant supported research to engage the permanent protection of the first conservation imperative sites in India, Indonesia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Brazil. In May 2024, the first Conservation Imperatives grant for land conservation will be sent to Jocotoco Foundation, an Ecuadorian biodiversity conservation nonprofit to expand a protected area of biodiverse cloud forests.

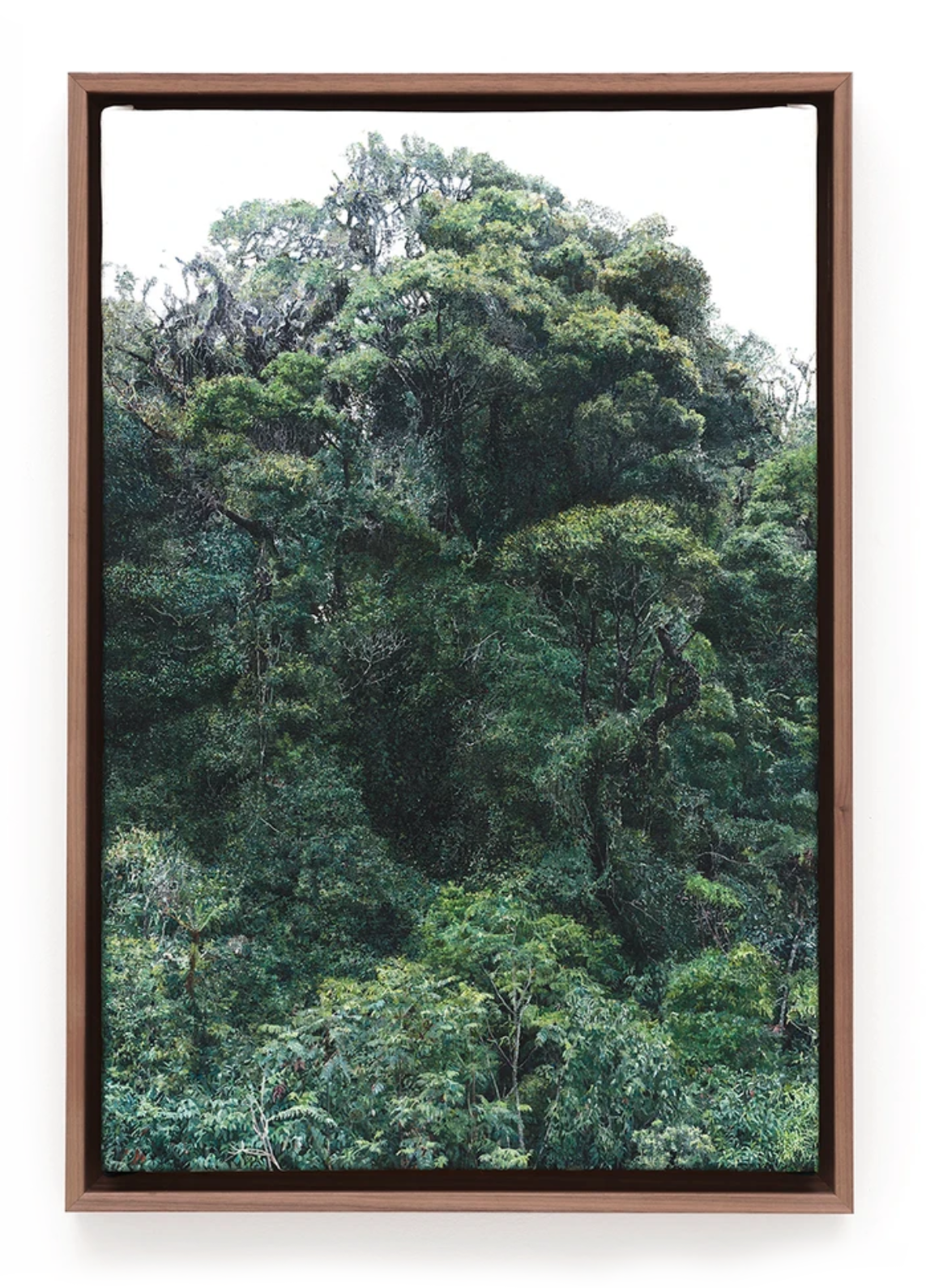

Haley Mellin, AV 15.4796°N, 90.774°W, 2022, Gouache on canvas in artist’s frame, 25.75 x 17.75 in, [courtesy of Thomas Mueller and The Journal Gallery]

Haley Mellin, CT 15.4646°N, 90.7794°W, 2022, Gouache on canvas in artist frame, 12.75 x 10 in. [courtesy of Thomas Mueller and The Journal Gallery]

TSQ: I find it fascinating that an artist, in part, initiated this research. What do you think of artists’ relationship to the natural world in general? And also, what has your experience been of the art world’s relationship to nature over the years?

HM: When talking with artists about nature, many speak about their early childhood experiences outdoors. Whether it is a stone or a bug or a bird, our histories of looking at other species and natural objects are personal. I can’t speak for all artists. My relationship to the natural world has been one of curiosity, respect, and awe. When artists talk to me about early visual experiences, they often mention experiences in nature.

TSQ: That’s definitely true for me, in terms of my early experiences with nature having had a big impact on my experience of the visual world as a child, and being a guiding force in my artistic practice. I also agree that the relationship to nature in the art world has shifted quite a bit, most distinctly since the pandemic. I remember when there was an attitude in the art world that misinterpreted a concern for nature as not being concerned with the social. Invoking the biological was seen as essentializing and taboo—ultimately, I think, this revealed the Western world’s deep unease with nature and with collapsing the status of humans as animals. But today, especially in the aftermath of Covid, it seems more broadly accepted that the health of the natural world is an important, if not the most important, topic.

How do you think we can foster a culture of conservation in a contemporary, globalized culture?

HM: I think we can foster it with the less-is-more approach: less consumption, less rush, and less production. Conservation is a form of care, and when caring for something, when being in empathy, we are in a decentered position, like what Elaine Scarry writes about in “On Beauty and Being Just,” when she describes seeing a small fleck of a moth. When the needs of another being become our needs, we do not distinguish where one stops and the other begins. It is in this space of reciprocality and awareness where a culture of conservation is born.

Shifting our activities is a result of education, public dialogue, and communal sharing. Shifting our awareness in a community becomes a force multiplier. I appreciate the way you worded this question: “… a culture of conservation.” How would you answer the same question? How do we foster a culture of conservation in a contemporary, globalized culture?

Haley Mellin painting outdoors, Cloud Forest biome [courtesy of Dr. Philip Tanimoto]

Timur Si- Qin, East, South, West, North, installation view, 2018 [courtesy of the artist]

Timur Si- Qin, East, South, West, North, installation detail, 2018 [courtesy of the artist]

TSQ: To answer that question, I would ask why it is that Indigenous people are such good stewards of biodiversity in the first place. There is the statistic that Indigenous people protect 80% of our global biodiversity yet make up only 5% of the global population. Of course, as you mentioned earlier, there are legal definitions of Indigeneity based on the length of time that people have been living in a place. But it isn’t necessarily the length of time that people have been living somewhere that creates cultures of conservation. For most Indigenous cultures, there is a spiritual and religious component to fostering truly effective conservation cultures.

To paraphrase anthropologist Wade Davis, for Indigenous people, a mountain is a sacred deity, whereas for our Western culture, a mountain is essentially a pile of rocks. Whether one perspective or the other is true or not is beside the point, but the outcome is that one of these worldviews leads to long-term, effective conservation. For the other, it is not unreasonable to mine or remove a mountain entirely for its minerals and utility.

And on a slightly different layer, I think that what is often overlooked from a Western point of view is that a conservation culture can be motivated by something other than fundamental utility. For example, from an agrarian perspective, nature becomes a set of “resources” we must manage to feed and shelter ourselves. This is, of course, true, but often it is our motivation to be fed and sheltered in the short term that leads to environmental destruction. Rather, in Indigenous cultures, it is the spiritual and religious dimension that plays a fundamental role in valuing the natural world for what it is.

HM: I agree. How do you define spirituality?

TSQ: I would define spirituality as an emotion of interconnection and situatedness in the larger context of the world. This is a powerful emotion that can motivate people in powerful ways, good and bad.

I think the work of biologist David Sloan Wilson can be illuminating in thinking about how religions and worldviews are adaptations in themselves. He posits that if the mind is evolved to adopt beliefs, then those beliefs may not necessarily be true, and that in many instances, beliefs can be more adaptive and useful as they become less true. However, there is also no reason beliefs can’t be simultaneously true, valuable, and spiritual.

With this knowledge, the question then becomes, how can we tap into this emotion of spirituality for the natural world in the contemporary? As Westerners, we don’t have access to Hopi or Chukchi religion. Nor should we, necessarily. Then again, the major religions we do have easier access to are agricultural or pastoralist in origin, and therefore, in our culture, nature is seen as utilitarian and under the dominion of man.

Maybe contemporary art can evolve to play this role. In some ways, art is already acting as a contemporary global religion. The most revelatory aesthetic experience is spiritual in nature—one of the few spiritual experiences available in contemporary secular society. I think, at its best, art is a celebration of difference and diversity—the connective tissue of culture that binds us together, mind to mind, heart to heart.

HM: The notion of a cultural connective tissue makes me think of your suspended sculpture Sacred Footprint, installed currently at Meta in New York City. How did the idea for this installation come to you?

Timur Si- Qin, Sacred Footprint, installation view, 2022 [courtesy of the artist]

TSQ: Sacred Footprint, title and all, came to me fully formed in a ceremonial vision. It is a tree consisting of different species of trees, mostly ones 3-D–scanned in upstate New York, which is a region that I think has some of the most beautiful trees in the world. The different trees link together like a chain and, for me, represent an ecological web—the relationships between species and organisms to form a higher-level entity. Diversity creating resilience.

HM: Last year, when in Berlin for a residency with the Neue Nationalgalerie and the American Academy, I viewed your exhibition Natural Origin at Société. The works shifted out of the symbolic and into the realm of direct experience, interconnecting shapes and forms of nature, weightlessly and multidimensionally. I resonated with your contemporary visual questioning of deep time, ecology, and evolution. Later, we sat outdoors, behind the gallery, and talked about conservation, nature, and speciation.

TSQ: I think that you and I both approach the natural world similarly with our work. In a meditative and devotional way, in which we try to look deeper and deeper into the visuality and details of nature. Somehow, for me, it is the specificity of the natural world that I find important—how the same species of flower can look different from one hill to the next. Or how the bottoms of leaves tend to be more matte, and glossy on top. It’s this detailed specificity that always seems to combine to form perfect chords and visual harmonics in unique combinations—with, somehow, always perfectly balanced yet counterintuitive color palettes.

How do you think about your artistic practice in this context?

HM: When I was about 13, I began drawing and painting outside. A stone, a hilltop. Painting and drawing outside was a restorative time to explore beyond the limits of my knowing, and beyond the limits of myself. Nature is somewhat an enigma. While painting observations of nature, a gap opens in my mind, thought ceases. For a short period, my mind quiets.

Timur Si- Qin, Natural Origin, installation view, 2023 [courtesy of the artist]

When I sit and look at nature and draw, I’m looking at the manifestation of long periods of time, often tens or hundreds of millions of years. On the surface, now, is life. I like drawing plants and trees that I share present time with. Trees and plants are the flowering of time, the very surface of a long story that stretches back into more slowness and more patience and more wisdom than I can fathom.

TSQ: I love this idea that plants are the flowering of time. In a way, I see that thought connecting with a contemporary idea of faith. We think of the universe as chaotic, deterministic, but mysteriously it is also a very aesthetic universe. Somehow the chaos of reality is deeply structured and quite exquisite. The morphology of a flower is a representation of the morphogenesis of time itself. If it happens at the scale of a flower, and at the scale of a galaxy, it is most likely happening at all scales, including the scale of our individual lives. I think this is a lesson that nature teaches and that has been a consistent source of hope and faith in my own life, a faith in the flower of time.

Haley Mellin is an artist and land conservationist. She founded the nonprofit organization Art into Acres to support large-scale land conservation; to this day, it has supported 64 new protected landscapes focusing on biodiversity conservation. To engage climate sustainability in art communities, Mellin co-founded Conserve.org (New York, 2017); the MOCA Environmental Council (Los Angeles, 2020); Art and Climate Action (San Francisco, 2020); Artists Commit (New York, 2020) and GCC New York (New York, 2023). Mellin focuses on observational painting in nature and currently has a 2024 show at Dittrich & Schlechtriem in Berlin. A graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, Mellin received a PhD from New York University in Visual Culture and Education, and attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program.

Timur Si-Qin b. 1984, Germany is a New York-based artist of German and Mongolian-Chinese descent who grew up in Berlin, Beijing, and in the American Southwest. His work has been extensively shown in solo exhibitions in Europe, the United States, and Asia, and was included in exhibitions at The High Line, New York; Schirn, Frankfurt; K11 Art, Shanghai; Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris; Ullens Contemporary Art Center, Beijing; The Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; and Kunsthalle Wien, among many others. He has participated in large-scale international exhibitions such as the Bangkok Art Biennale, Bangkok; Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennial, Saudi Arabia; Kunsttriennale Beaufort, Belgium; Riga International Biennial Of Contemporary Art, Latvia; Ural Biennale, Russia; 9th Berlin Biennale; Germany; and

Taipei Biennial.