Interview: David Hammons

Share:

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS July/August 1988, a special issue on contemporary Black artists.

In 1987, David Hammons created a permanent sculpture for down-town Atlanta. Now located in Piedmont Park, the work, entitled Free Nelson Mandela, is composed of wrought iron bars with a locking door reminiscent of a jail cell, embedded in concrete and topped by barbed wire. In typical Hammons style, the artist has created a story to go along with the piece. He claims that he has buried the key to the wrought iron door under the work, and that when the jailed Mandela is freed in South Africa, Hammons will unlock the door to his piece in Atlanta. South Africa has been a recurrent theme in the artist’s work. He developed a set of prints depicting Mandela’s portrait which he applied guerrilla-fashion to various surfaces around New York City. An example was displayed in the recent “Committed to Print” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Hammons has since 1985 shown various versions of Soweto Market, a site-specific sculpture in which an ordinary fruit stand is transformed into an arsenal of grenades camouflaged as oranges and lemons. This interview is adapted from Real Life, where it appeared in Autumn, 1986.

David Hammons: I can’t stand art actually. I’ve never, ever liked art, ever. I never took it in school.

Kellie Jones: Then how come you do it if you can’t stand it?

DH: I was born into it. That’s why I didn’t even take it in school. All of these liberal arts schools kicked me out, they told me I had to go to trade school. One day I said, “well, I’m getting too old to run away from this gift,” so I decided to go on and deal with it. But I’ve always been enraged with art because it was never that important to me. We used to cuss people out: people who bought our work, dealers etc., because that part of being an artist was always a joke to us.

But like someone told me: “Art is an old man’s game, it’s not a young man’s profession.” Most people can’t deal with all the loneliness of it. That’s what I loved about California though. These cats would be in their ‘60s, hadn’t had a show in twenty years, didn’t want a show, painted everyday, outrageous stamina. They were like poets, you know, hated everything walking, mad, evil; wouldn’t talk to people because they didn’t like the way they looked. Outrageously rude to anybody, they didn’t care how much money that person had. Those are the kind of people I was influenced by as a young artist. Cats like Noah Purifoy and Roland Welton. When I came to New York, I didn’t see any of that. Everybody was just groveling and tomming, anything, to be in the room with somebody with some money. There were no bad guys here, so I said “let me be a bad guy,” or play with the bad areas and see what happens.

In Los Angeles, Senga Nengudi and I shared a studio. Her work was so conceptual and I was working in frames. By us sharing a studio, she got more figurative and I got more conceptual. That’s when she started doing the pantyhose; those pieces are all anatomy. This was the ‘60s; she used to put colored water in plastic bags and sit them on pedestals. No one would even speak to her because we were all doing political art. She couldn’t relate. She wouldn’t even show around other Black artists her work was so “outrageously” abstract. Senga came to New York and still no one would deal with her because she wasn’t doing “Black Art.” She was living in Harlem. So she had to leave here and go back to L.A. and regroup. Then I came in after her, I said “I’ll try it, I’ll try it with my shit.”

It was a totally different thing when I came here in 1974. It was a painter’s town exclusively. If you weren’t painting you could forget it. I was doing body prints then and was moving into conceptual art. I had to get out of the body prints because they were doing so well. I was making money hand over fist. But I had run out of ideas, and the pieces were just becoming my ordinary, and getting very boring. I tried my best to hold on to it. It took me about two years to find something else to do.

I came here with my art in a tube. I had a whole exhibition in two tubes. I laid that on the people here and they couldn’t handle it, nothing in it was for sale. This was after the body prints. This was after I had taken off for a couple of years and come up with an abstract art that wasn’t salable. These things were brown paper bags with hair, barbecue bones and grease thrown on them. But nothing was for sale. Other Black artists here couldn’t understand why you would do it if you couldn’t sell it.

I was influenced in a way by Mel Edwards’ work. He had a show at the Whitney in 1970 where he used a lot of chains and wires. That was the first abstract piece of art that I saw that had a cultural value in it for Black people. I couldn’t believe that piece when I saw it because I didn’t think you could make abstract art with a message. I saw symbols in Mel’s work, then I met Mel’s brother and we talked all day about symbols, Egypt and stuff. How a symbol, a shape has a meaning. After that, I started using the symbol of the spade; that was before I did the grease bags. I was trying to figure out why Black people were called spades, as opposed to clubs. Because I remember being called a spade once, and I didn’t know what it meant; nigger I knew but spade I still don’t. So I took the shape, and started painting it. I started dealing with the spade the way Jim Dine was using the heart. I sold some of them. Stevie Wonder bought one in fact. Then I started getting shovels (spades); I got all of these shovels and made masks out of them. It was just like a chain reaction. A lot of magical things happen in art. Outrageously magical things happen when you mess around with a symbol. I was running my car over these spades and then photographing them. I was hanging them from trees. Some were made out of leather (they were skins). I would take that symbol and just do dumb stuff with it, tons of dumb ignorant corny things. There’s a process to get to brilliancy: you do all the corny things, constantly empty the brain of the ignorant and the dumb and the silly things and there’s nothing left but the brilliant ideas. Pretty soon you get ideas that no one else could have thought of because you didn’t think of them, you went through this process to get them. Hopefully you ride on that last good thought and you start thinking like that and you don’t have to go through all these silly things, again.

It was just like a chain reaction. I started doing body prints in the shape of spades. Then I started painting watercolors of spades. After that, I stopped using the framed format entirely; I had chains hanging off the spades. I went to Chicago to a museum and saw this piece of African art with hair on it. I couldn’t believe it. Then I started using hair.

KJ: So where did you get the hair from, barber shops? People didn’t want to give it up, did they? They thought you were going to do some serious magic on them using that hair.

DH: No they didn’t mind it. Except there was a place in Harlem that said no they wouldn’t give it to us, this Haitian place. In L.A. I had one place that I got hair from, this one shop, because it was so hard to ask people. I’d wait until everyone left the shop, I’d sit out front until the shop closed. I would always ask this one guy. Eventually, I got used to him and he got used to me. In New York, I wouldn’t get the hair. I had this friend get if for me. He was very outgoing, you know, sold you insurance and all that kind of stuff, a gallery dealer, he’d talk to anybody. He’d talk to the barber and I’d just pick up the hair.

There’s so much stuff that I want to do with the hair that I didn’t get a chance to do, because I just can’t stay with any one thing. Plus I got really bad lice. Everyone kept telling me I was going to get lice. I shrugged it off as just a possible occupational hazard. Hair’s like the filthiest material. It’s a filter. When the wind blows through it the dirt stays on the hair. You could wash your hair every single hour and it would still be dirty. But I have information on Black people’s hair that no one else in the world has. It’s the most unbelievable fiber that I’ve ever run across.

I was actually going insane working with that hair so I had to stop. That’s just how potent it is. You’ve got tons of peoples’ spirits in your hands when you work with that stuff. The same with the wine bottles. A Black person’s lips have touched each one of these bottles, so you have to be very, very careful. I’ve been working with bottles for three years and I’ve only exhibited them a couple of times. Most of my things I can’t exhibit because the situation isn’t right, no one is taking the shit seriously anymore. And the rooms are almost always wrong, too much plasterboard, overlit, too shiny and too neat. Painting these rooms doesn’t really help; that takes the sheen off but there’s no spirit, they’re still gallery spaces.

I think the worst thing about galleries is, for instance, that there’s an opening from 8-10pm. The worst thing in the world is to say, “well I’m going to see this exhibition.” The work should be somewhere in between your house and where you’re going to see it, it shouldn’t be at the gallery. Because when you get there you’re already prepared, your eyes are ready, your glands, your whole body is ready to receive this art. By that time, you’ve probably seen more art getting to the spot than you do when you get there. That’s why I like doing stuff better on the street, because the art becomes just one of the objects that’s in the path of your everyday existence. It’s what you move through, and it doesn’t have any seniority over anything else.

Everybody knows about Higher Goals—the telephone pole piece—up here in Harlem. If I’m on the street up there I say, “I’m the guy who put that pole up there.” I’ll be on 116th or 110th and Amsterdam and talk to anybody and they’ll say; “You’re the one who did that. Yeah, I know where that is, I know you. Brother, come here, this is the cat who did the pole, yeah.” So sometimes I’ll just say that to talk to somebody on the street, at three or four in the morning or something, it’s like a calling card. I’ve been trying to put it in the Guinness Book of World Records as the highest basketball pole in the world but I don’t know who to call.

I like playing with any material and testing it out. After about a year, I understand the principles of the material. I try to be one step ahead of my audience. Some artists are predictable. You’ve seen their patterns over the last ten years. They’re staying within these frame-works because it’s financially successful. I look at these cats and this is what I never want to be or never want to do. Why should I stay safe? It takes a long time to analyse a form—whether it be metal, oil paint, whatever—it may take them their whole lifetime to analyze this material. But who gives a fuck? There are so many things to play with. I question if what these artists are doing is art or not. I don’t think it is. An artist should always be searching for things. Never liking anything he finds, in a total rage with everything, never settling or sacrificing for anything. That’s what I enjoy anyway I always try to use materials that are not easy to obtain. Like now I have all this elephant dung that I’m working with.

KJ: How did you get that?

DH: It was for a garden. Angela (Valerio) was getting some for her plants. I was there with her and saw some of this elephant manure. It was interesting. It’s about the size of a coconut. So I’m painting on it now. I’ve been working with it since about April 1985.

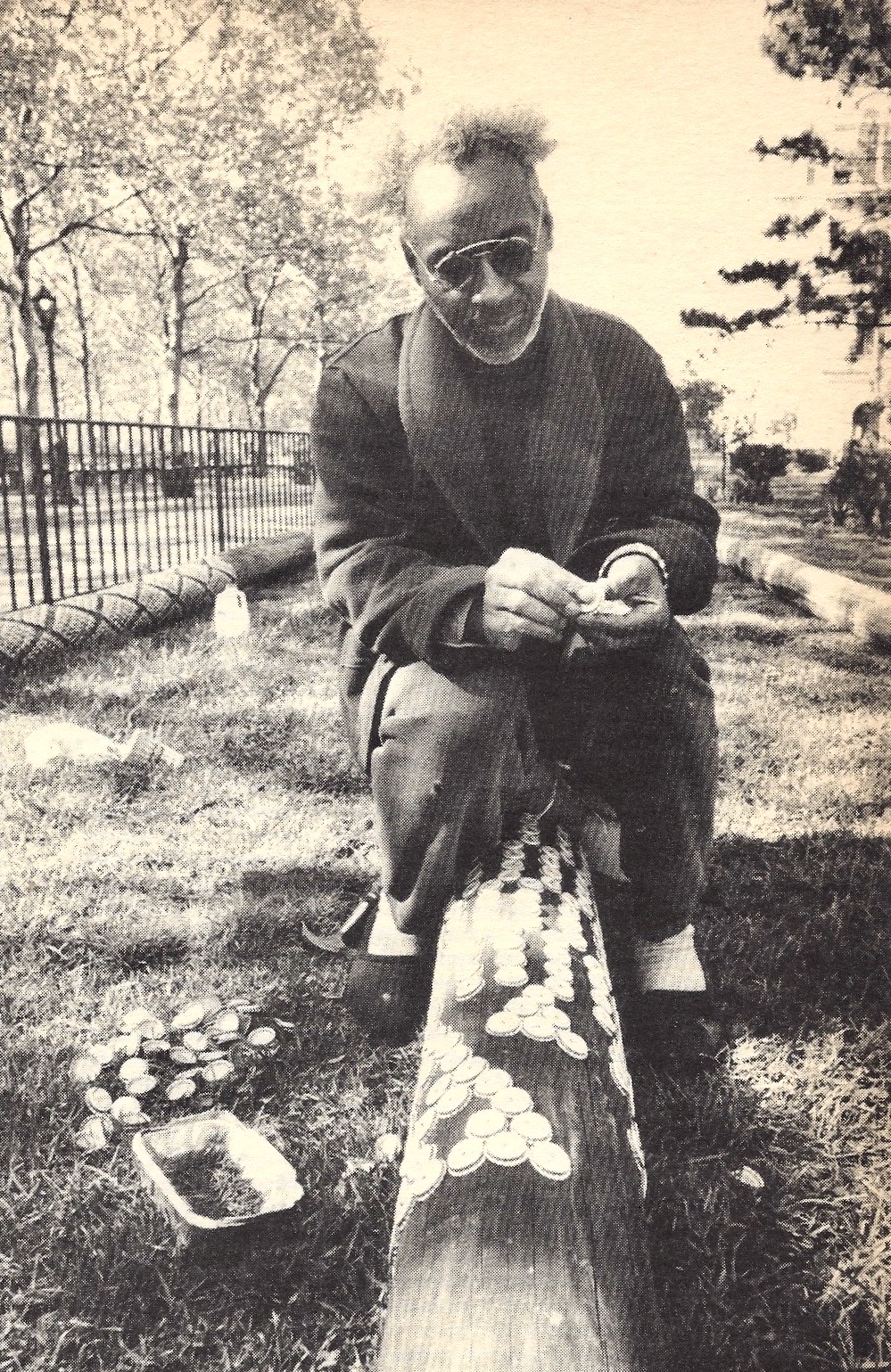

David Hammons at work on Higher Goals (1986), Brooklyn, NY [photo: Russell Nash]

KJ: You did pieces for a while that had dowels with hair and pieces of records on them. Like the piece you did for the Atlanta Airport.

DH: Those pieces were all about making sure the black viewer had a reflection on himself in the work. White viewers have to look at someone else’s culture in those pieces and see very little of themselves in it. Like looking at American Indian art or Egyptian art—you can try to fit yourself in it but it really doesn’t work. And that’s the beauty of looking at art from other cultures, that they’re not mirror reflections of your art. But in this country, if your art doesn’t reflect the status quo, well then you can forget it, financially and otherwise. I’ve always thought artists should concentrate on going against any kind of order, but here in New York, more than anywhere else, I don’t see any of that gut. It’s so hard to live in this city. The rent is so high, your shelter and eating, those necessities are so difficult, that’s what keeps the artist from being that maverick.

KJ: It’s funny though, because people always think that the starving artist is the most important one. That all the angst and starvation is what makes your art good.

DH: It does make your work good if you understand the starvation. Like Van Gogh said, he who lives in poverty and loves that poverty that he lives on will always be in the heartbeat of the universe. But you have to love the poverty, and there are very few people who love poverty; they want to get out of it. So if you are in poverty and dislike it, well then you have a real problem and it’s going to reflect in the work. But if you’re in poverty and enjoy it and can laugh at it, then you have no allegiance to anything and you’re pretty much free.

Anyone who decides to be an artist should realize that it’s a poverty trip. To go into this profession is like going into the monastery. To be an artist and not even to deal with that poverty thing, that’s a waste of time; or to be around people complaining about that. Money is going to come, you can’t keep money away in a city like this. It comes but it just doesn’t come as often as we want.

My key is to take as much money home as possible. Abandon any artform that costs so much. Insist that it’s as cheap as possible and also that it’s aesthetically correct. After that anything goes. And that keeps everything interesting for me.

KJ: Would you say that your work has any political element in it? By abandoning running after money, does the work become more political in a certain sense?

DH: I don’t know. I don’t know what my work is. I have to wait and hear that from someone.

KJ: Like who, regular people on the street?

DH: They call my art what it is. A lot of times I don’t know what it is because I’m so close to it. I’m just in the process of trying to complete it. I think someone said all work is political the moment the last brushstroke is put on it. Then it’s political, but before that it’s alive and it’s being made. You don’t know what it is until it’s arrived, then you can make all these political decisions about it.

Sometimes I do say, “this is going to be a political piece.” Like Soweto Marketplace that was at Kenkelaba House (“Dimensions in Dissent,” December 1985). Then trying to make it is so difficult, because I want it political and I want it conceptual and I want it visually interesting. I want it gloomy, I want it hidden away from the crowd. All these kinds of things come into play. So I’m dealing with about five different levels.

I’m learning a lot from Fellini, watching his movies over and over again. I think the movie people are much more advanced than other visual artists. They can make you cry, they can make you laugh, they can scare you. Paintings don’t do that, they used to but not any more because the audience knows the game too well. But it’s the artists fault because the artist isn’t researching and making the game more real. We’ve let filmmakers take the game from us because of our nonchalance.

If you know who you are then it’s easy to make art. Most people are really concerned about their image. Artists have allowed themselves to be boxed in by saying yes all the time because they want to be seen, and they should be saying no. I do my street art mainly to keep rooted in that “who I am.” Because the only thing that’s really going on is in the street; that’s where something is really happening. It isn’t happening in these galleries. Lately I’ve been trying to meet a new kind of people in this city and not the art scene. Otherwise you end up with, “Man, you shit’s baaad, your shit’s happening you’re the man,” all this absurd praise. You start flying and thinking that your shit don’t stink. I’ve invented a rule book for myself, that’s gotten me over all of this stuff. If an artist doesn’t have his own rules then he’s playing with those of the art world, and you know those are stacked against you.

I have all these safety valves that I use. Like if it’s on the ground, I pick it up and put it on a branch. It’s still outside of me, I just found it. One artist accused me of “showing a bad image of Harlem.” And I said, “I’m not showing anything, I’m just putting what’s on the ground onto a tree. I’m not responsible for the wine bottle getting there. All I’m doing is playing with it, activating it in some form.”

Selling the shoes and other things on the street I think is my personal best; those little shoes, that’s my best shot. I do it whenever I need a fix, I guess; when I know I need attention and want to make someone laugh. It’s like having an opening, when I do that piece because I interact with the people. And I don’t have to wait for these galleries. It’s a way for me to show people how I see the world. I get a chance to watch people interact. It’s interesting…if you have an item between you and other people, then they can relate to you. If you don’t have an item you’re enemy number one. But if you have an item between you then it cools them out and they can deal with you. It’s amazing how something like a little shoe can just turn someone’s head around.

KJ: Have you ever talked to people on the street—like when you had the bottle tree piece in the vacant lot next door to the Studio Museum, did you ever stand around there and listen to what ordinary people said about it?

DH: I was there one time and some people asked me what I was doing and somebody said, “He ain’t got nothing better to do.” And I thought, I didn’t have anything else to do, that was the reason I was doing that. So they ask the questions and answer them themselves. If you’re quiet or don’t have anything to say, they say it all for you.

KJ: Do you think everyday people have a greater grasp of what you’re doing than…

DH: Than I do.

KJ: …than you do or than other people who are politically astute, or versed in art?

DH: They’re the number one, because they’re already at the place I’m trying to get to. Sometimes I carry a whole arch of wine bottles around in the neighborhood. I walk from 125th up to 145th street and people follow me, ask me questions, give me answers, tell me what I can do. They just give me tons of information and I don’t give them any. I’m just carrying this piece around like it’s a log or something. Once, a woman said to me, “Mr., excuse me, but could you please tell me what that is?” I said, “What are you speaking of?” Then I said, “Oh, it’s just some wine bottles.” I play off it. I do this every once in a while to cleanse myself. It’s putting myself out there on the street to be made fun of. I think it’s important to be laughed at.

Black people, we have more problems with being made fun of than any other people I’ve ever met. That’s why it’s so important for us to be cool, cool, cool. If you’re not cool then you’re something else and no one wants to be that other thing. But the other thing is what I’m interested in, because you have to really work at getting to that other space. Black artists, we are so conservative that it’s hard to get there, you have to work at it, really, really work to be non-conservative. We’ve come up under this Christian, puritanical, European form of thinking and it’s there, deep rooted. It can be worked at, loosened up some, but it’s very difficult. What happens with my work is like I’ll be working on piece “A” but I’ll do some little aside things on my way across the studio to get to piece “A” and these aside things will be more important because they are coming out of my subconscious. These aside pieces will become more interesting and haphazardly loose and piece “A”, that I’ve been working on for months, will be real tight.

Doing these things in the street is more powerful than art I think. Because art has gotten so…I don’t know what the fuck art is about now. It doesn’t do anything. Like Malcolm X said, it’s like novocaine. It used to wake you up but now it puts you to sleep. There’s so much of it around in this town that it doesn’t mean anything. That’s why the artist has to be very careful what he shows and when he shows now. Because the people aren’t really looking at art, they’re looking at each other’s clothes and each other’s haircuts. In other sections of the country I think they’re into seriously looking at art. This is the garbage can of it all. Maybe people shouldn’t look at art too seriously here because there’s so much.

The art audience is the worst audience in the world. It’s overly educated, it’s conservative, it’s out to criticize not to understand, and it never has any fun. Why should I spend my time playing to that audience? That’s like going into a lion’s den. So I refuse to deal with that audience and I’ll play with the street audience. That audience is more human and their opinion is from the heart. They don’t have any reason to play games, there’s nothing gained or lost.

KJ: The piece that was at “Art on the beach,” does it have a name?

DH: I called it Delta Spirit because it was about that kind of spirit that’s in the South. I just love the houses in the South, the way they built them. That Negritude architecture. I really love to watch the way Black people make things, houses, or magazine stands in Harlem, for instance. Just the way we use carpentry. Nothing fits, but everything works. The door closes, it keeps things from coming through. But it doesn’t have that neatness about it, the way white people put things together; everything is a 32nd of an inch off.

So working with the architect was fun because our shit was outrageous. You had to have an architect on this project. So I hired Jerry Barr, we did Higher Goals together in 1983. He came up with the structure of Delta Spirit, he designed it. It was very puritanical. You know he’s a big time architect, all over the world. He’s designed houses in Paris, Cuba and Africa. So this was one of his concepts. What I had to do was take that concept and put Negritude in it, which was a porch. He wanted to buy brand new wood; he wanted to spend about one thousand dollars on wood. But I had found all this lumber in Harlem and had stacked it up in these piles on various corners. So we just went around with a truck and picked up all the lumber, took it downtown and started making the house. It was built in the shape of a hexagon, a six-sided figure, using six foot poles, everything is six feet long.

KJ: Was that your idea?

DH: No, that was Jerry’s. I don’t know how to stack wood, to keep wood from falling down. That’s why he was important to the project. He knew how to stack wood and he knew how to get the best piece of wood. I was just going to build a lean to, a little shed, and take all the money and go home.

KJ: Do you think by doing a piece as cheaply as possible, that puts you on the same footing with a lot of people who are trying to survive? Like you said, these newspaper stands in Harlem, I mean obviously these people are not going to spend three thousand dollars on wood…

DH: Exactly. But these stands serve the same functions and do the same things. They’re just aesthetically different.

KJ: When you were doing Delta Spirit did you go down South and look at houses, or did you make the piece from memory?

DH: It’s based on memories of the South. It also had a lot to do with Simon Rodia’s Watt Towers. I love his work, it’s one of the best. When I was in L.A. these towers just really influenced me. I would like to work on one piece for the rest of my life; just one piece, like him. Most artists want at least one piece to be immortalized. So one piece would do it. Because we’re making one piece anyway, I guess, fragments of it.

KJ: To me, Delta Spirit was a conglomerate of black people’s living. The way they put things together. It’s not exactly the way a white or European person would do it.

DH: But it transcended that and went on into another level. Its significance changed as it got more and more ornamented; as it got more detailed, it went universal. People started seeing it who were from places like Tibet and Vietnam, for instance, and told us about houses they’ve seen like that in all corners of the world. Getting this type of feedback also affected the piece.

KJ: The pieces that you are doing now with bottles, your standard wine bottle with things like crosses and the Georgia clay inside of them. Are they related at all to the Thunderbird bottle pieces that you were doing before?

DH: With the bottles I’m using now, I got the inspiration from the book Flash of the Spirit (by Robert Farris Thompson). On one page I saw this little juju man sitting up there with a cross in a bottle. The thing I love about these bottles is that people have to ask how you got those things in there. It’s like they’re saying, “how’d you do that trick?” Or I get this from people, “Oh. I know how you did it, you took the bottom off the bottle and glued it back on.” And I say, “Yeah, that’s how I did the trick.” But visually it’s hard now to mess with people because everybody is so hip on what’s happening. I like when people ask how I do these things because that means they don’t know. Whereas in a painting everybody knows, or everybody thinks they know “it’s an extension of such and such school,” that kind of stuff. So I’m trying to find these holes or these gaps to play in.

I just finished a piece with a voodoo doll in the bottle. That was fun. And then there’s the bottle caps. I love bottle caps. Because I can get trillions and billion and zillions of those things. Whatever you see a lot of, you can use, you can build something off of. So I want to work with them forever. I also want to come back to the hair. All of these things I want to come back to at another time. Now I’m just laying down some kind of foundation; these pieces are like visual notes, like how to put in your notebook. These are all notes to come back to at another time, elements to reconnect in the future. The hair, the bottle caps, the bottles, they’ll all represent themselves in another salad on up the road somewhere.