Greg Ito: Looking Back to Let Go

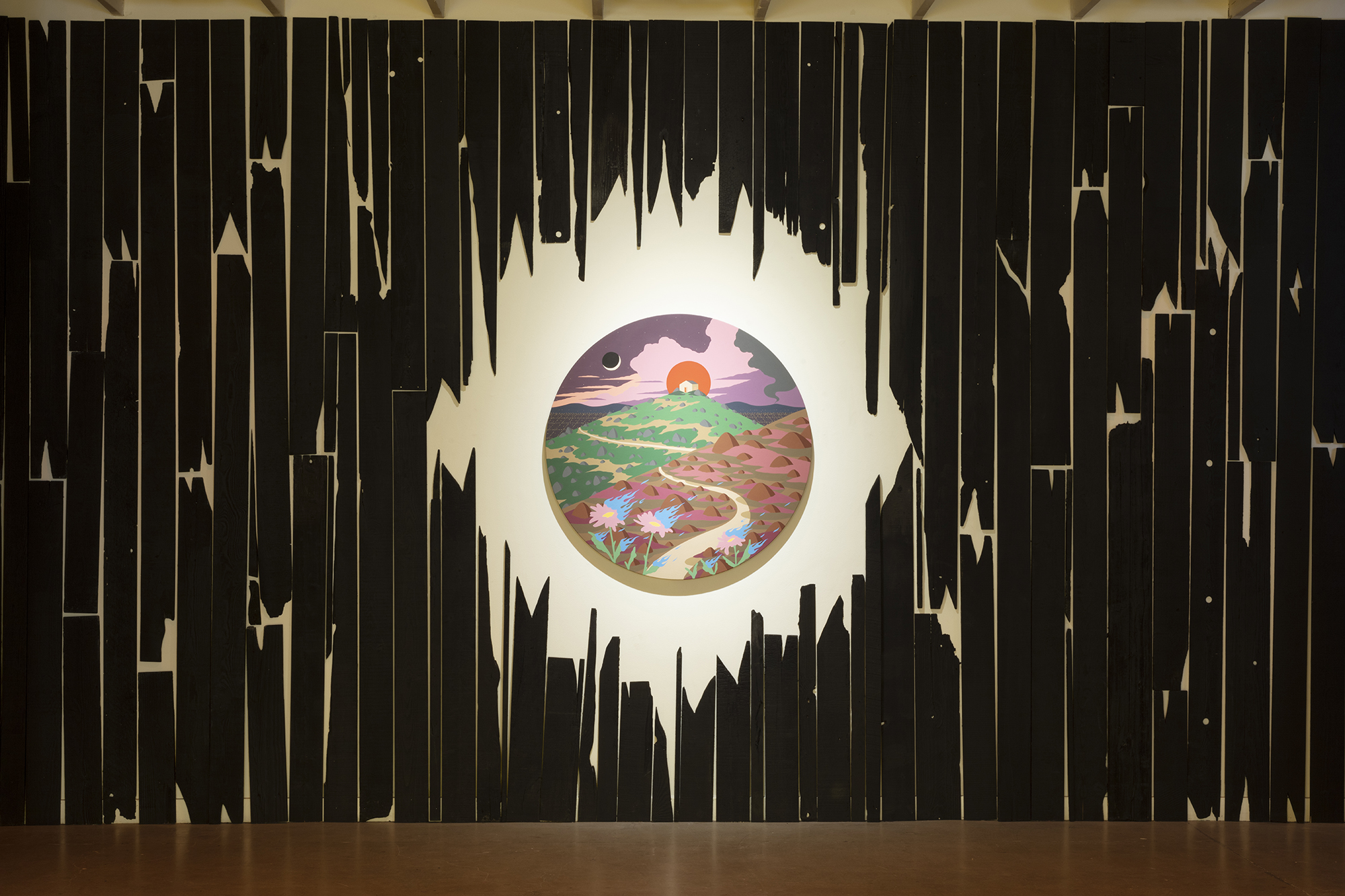

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, Installation view, 2022 [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and ICA San Diego]

Share:

Los Angeles–based artist Greg Ito describes his solo exhibition All You Can Carry, on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, San Diego (March 12–May 15, 2022), as his most personal work to date. Presented across two galleries is an installation of paintings, sculptures, and wall and lighting treatments that speak to Ito’s unique visual lexicon, in which flattened, clip-art-style images of suitcases, houses, flora, fauna, fires, and keyholes, are arranged across LA-inspired landscapes. These elements speak to questions of home and identity from the perspective of a fourth-generation Japanese American Angeleno.

Ito is showing archival photographs alongside his paintings for the first time. They depict his grandparents’ lives during and after their internment at the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona. They fell in love there after joining the thousands of Japanese Americans forced into internment following the 1942 Executive Order 9066, signed after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Of particular significance is an illustration of that camp by Ito’s grandfather, who was a talented cartoonist. The scene predicts the homes in waterside towns that feature so prominently in Ito’s landscape paintings, often organized by a line of window frames through which viewers look into Ito’s world.

In this conversation, Ito walks us through All You Can Carry, describing the meanings and resonances behind the paintings, photographs, and objects on view.

Stephanie Bailey: Could you introduce your show at ICA San Diego?

Greg Ito: I’m using this institutional platform … to connect my artwork with the actual experiences of my grandparents and great-grandparents in the Japanese internment camps during World War II ….

I always say that the way to enter my work is through this narrative of my grandparents’ story: how they met, how their relationship was forged in this darker moment of history—in our family’s history—which was a very traumatic time.

My family never really talked about their time in camp that much, but I know that it was super difficult from what they’ve told us. The story that really stuck with me was how my grandparents kind of knew each other before, in Los Angeles, a little bit, but it was in the camps where they fell in love. My grandfather courted [my grandmother] by making these small handmade carvings for her with her name engraved in them—these little, delicate wood sculptures that resembled the deer and rabbits from the animation Bambi, which was popular at the time. It was released shortly after they arrived in camp in 1942.

Everybody in the camps had their duties. It wasn’t like a government-staffed facility. They had guards who watched the inmates, who each had their jobs, like being a nurse, doing yardwork, or being a watchman, which was my grandfather’s job—to watch this water tower that was at the very top of this hilltop in the desert. He would have to walk up to this hilltop to watch the water tower and from there he would look over the whole camp knowing that his girlfriend, his future life partner, was down there. I like to imagine him carving these little gifts [while he was up there].

I wanted to connect my work more closely with the history of their union, and this story of transformation and perseverance, by taking the opportunity to show multiple facets of my practice in tandem with family ephemera in the exhibition. So, I’m showing a collection of family photos from this scrapbook that my grandfather started to make after the war, which he never finished. He was actually a cartoonist during that time. As an artistic outlet, he drew, painted signs, and tinkered in his workshop. We [still] have some small objects he made.

There are these pages from my grandfather’s scrapbook, which show him and his brother at the camps in zoot suits, because that’s what they wore outside of the camps. There is one image from camp where you can see the geography and landscape from the hilltop he was stationed at. And you see at the top of this hill, there’s the water tower.

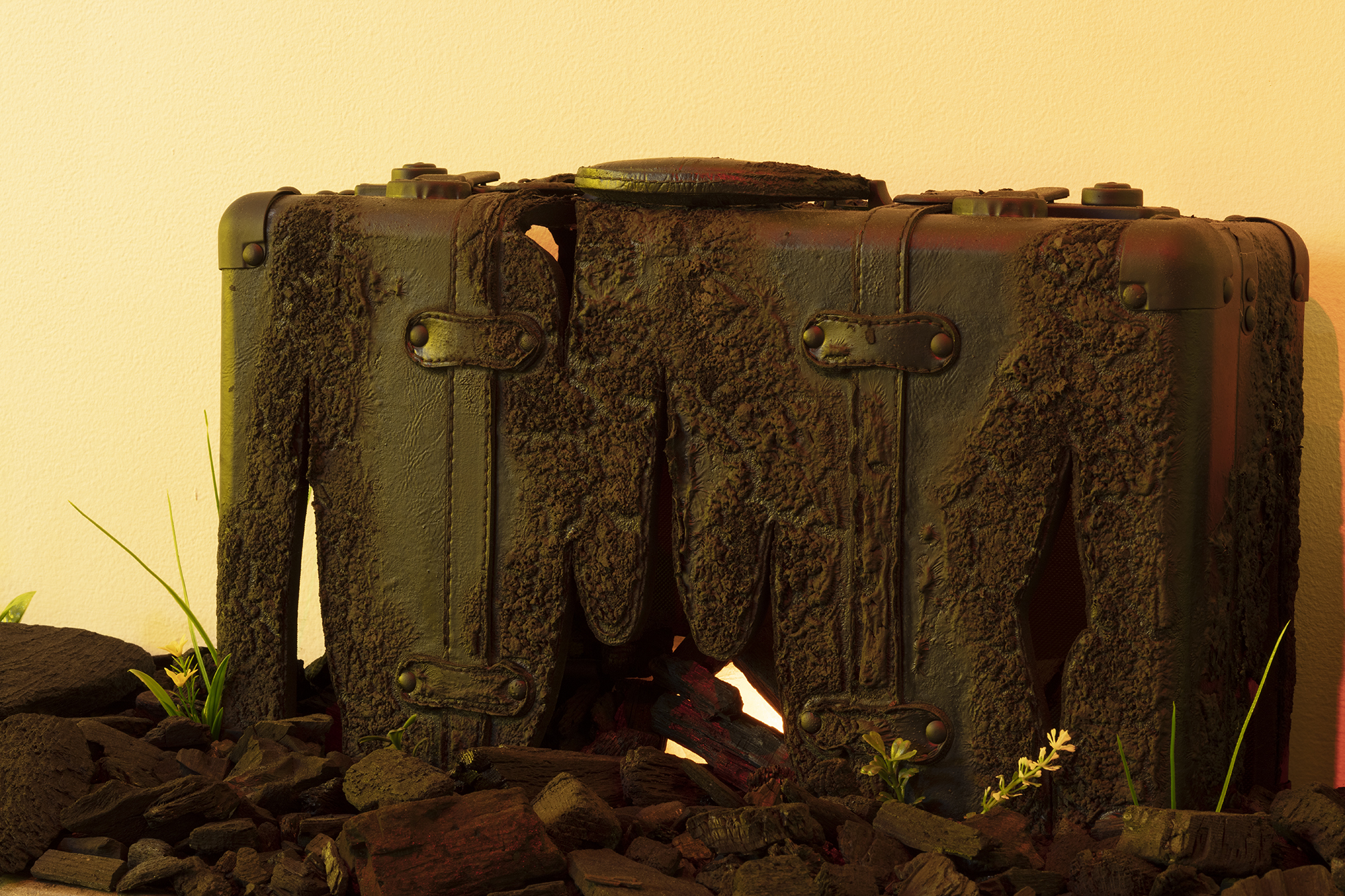

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, Installation detail, 2022 [Courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and ICA San Diego]

SB: This is amazing; looking at your grandfather’s sketch, you can see how that fed directly into your window landscapes in particular—that form of the house is mirrored in the shape of these barracks.

GI: Right. The first page of my grandfather’s scrapbook is a sketch of a title page that he started, which says “Our Story,” with his name at the bottom—it’s just the initial kind of pencil sketch that cartoonists or sign painters normally start with before they lay down paint or ink. But he never inked this page; he never finished his scrapbook. I don’t think that’s a bummer at all. It just shows how, when things aren’t fully recorded, stories become oral histories that get passed down, and just like [a] telephone game they start to shift; they become a little bit more of a memorialized memory—sometimes things become a bit more rounded, losing points that previous generations [took] to the grave. So, I’m just absorbing that reality—of how time changes, heals, but also destroys—for this show.

This is probably the most personal show I’ve made. I want people to know that the work is connected to these real experiences, so there’s pretty intimate stuff that’s only been seen within our family circle .… I had to ask my mom if it was okay to share these photographs. Since we weren’t able to get permission from relatives who have passed to share these things, all the faces are going to be covered with small white stickers. That way we can keep our family identities private and off the internet. These stickers also create a pathway for viewers to insert themselves into [my family’s] experience.

SB: Your paintings draw on this personal history, but render the images in such a way that they become symbols—abstractions that both refer to your family’s experiences but also resonate beyond them.

GI: The formal, painterly aspects of my paintings are speaking to my heritage as a Japanese Angeleno, from the color choices and compositions—which speak to this crisp, woodblock-print way of working with these layers that’s just innately ingrained in my identity—to the symbols and imagery, which visualize these narratives, like the symbol of the home. What is a home? What is home when it’s been taken away from you? What is home when you literally are kicked out of your home? When you are given one week to pack your suitcases and can only bring what you can carry?

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, Installation view, 2022 [Courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and ICA San Diego]

SB: That’s where the title of the ICA San Diego show comes in.

GI: Yeah. The walls are going to be covered in these fragmented, broken, burnt wood pieces, all painted black—that wall treatment speaks to the burning house. I like to call them treatments because that’s the word people use for design and architecture, like in the movie industry—building sets or designing an event where treatments are what you use as tools to build an experience. That’s what I want people to get from this show, to have an experience.

So, these burned walls speak to fire, which is destructive but also transformative; it makes room for growth and renewal. I like the balance between the destructive power of the flame and how the Japanese process of burning [cedar] on the outside of a house or structure is used to preserve it. I’m thinking about burning as a form of preservation; like when something burns you, it’s also instilling that moment. The installation also includes lighting treatments—orange, yellow, and reddish tones—that invoke a kind of fire, but at the same time also remind me of gold, something precious. Within that space is going to be one larger sculpture: a pyramid of burned suitcases with an aluminum-cast maquette of a house that looks like [it has] been burned. The suitcases are painted black, with a lot of holes and cracks with lighting elements on the inside that flicker like flames. More of these suitcases will also be garnished around the exhibition space.

So that’s it: You step into a room lit up with yellow and orange hues, with walls covered with burned planks of wood with paintings hanging on them. And on the ground are these burning suitcases that are glowing as if they’ve been burning all night. Then in the center is this pyramid that memorializes both the idea of home and the forced migration of Japanese Americans, which also speaks to multiple cultures and histories. Because while this is something that the Japanese American people have gone through, so many civilizations throughout time have been forced to leave their homes from war, sickness, natural disaster, and more.

SB: And while this is happening across two galleries, there is also a site-specific installation outside the exhibition.

GI: Once people leave the second gallery, there’s a courtyard, and from here you can see a hilltop. People are invited to get a little bag of California wildflower seeds and walk from the gallery to the top of this hill, where I have this outdoor sculpture. When you walk up to the top of the hill, there’s this footprint of a house—the burned remains of a structure.

When I visited the camp, I noticed that the only things that remained were cement staircases and the little foundation blocks that the structures were built on to keep them off the ground. There were also millions of nails on the ground from the structures. I wanted to create a footprint of a structure where the perimeter is made of burnt wood with a bed of charcoal in the center—creating this void of a home at the top of the hill—and in front is a cement staircase.

Greg Ito, Desert Oasis, 2022, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 48 x 36 inches [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles]

And the earth in the middle under the charcoal is tilled soil. People are going to be invited to throw the wildflower seeds into this plant bed, and over time flowers will grow through the charcoal.

I’ve never really done performance art before, but I really want to do something physical for this show. So, as a ceremonial ending performance, after people contribute the seeds through[out] the exhibition, I’m going to carry five–gallon buckets filled with water up the trail and water the seeds at the top of the hill. I want people to imbue their seeds with some kind of meaning—maybe they can use them to make a wish, or [think of] something they want to let go of. I want them to use the seeds as a transformative material that connects with the transformation that my grandfather experienced going up and down this hill when he was in the camp.

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, Installation view, 2022 [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and ICA San Diego]

SB: Which speaks to this view you have through your grandparents’ experience of the camp, where love ultimately won, as you’ve said before.

GI: You know, discussions about generational trauma are really present right now. I’ve talked about it a lot with my wife, who’s African American, and she’s like, “It’s so amazing for you to know where your ancestral roots are, but I don’t know where I originate from in Africa, or the Caribbean, or from here or there.” And she’s like, “You know, you should feel really blessed that you can trace your footsteps, because I can’t trace my footsteps all the way back.” That struck a chord with me. So as an ending gesture for the show, I want to water the seeds that everyone participated in planting in the outdoor sculpture, and to use that as a way for me to release some of these traumas from the internment camps so I can continue forward in my family’s story. My grandfather once expressed, “We had to be in the camps to prove that we were American.” Of course, all these discussions are complex, but what I want to do by carrying that water up the hill is to think of the water as their experience—maybe it’s my connection to their experience. So, when I carry these gallons of water— Much like their experience, it began heavy, overflowing with sadness and despair, and along the path the water spills. I’ll drink some of the water, or use it to cool me off, and in the end [I’ll be] left with only what remains and [I’ll] share it with participants and their seeds and the thoughts they imbued them with. My family’s story [will be] acting as water, activated as a transformative medium to make a garden of wildflowers that rise from the ashes.

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, 2022, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 48 x 36 inches [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles]

SB: I guess that’s the act of healing, right? Because they always say [that] to break the chain of generational trauma, you need a generation that’s willing to do the work to heal from it. I guess it’s the question of the tension between holding on and remembering, honoring that history and letting go. Because while you need to remember, that act of remembering can also be its own trauma. There is this condition, complicated grief, when grief intersects with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, so that grief becomes interrupted, because it’s too much to bear. You push it away, but in doing so, that grief also becomes endemic, frozen in time, to be lived through again and again in the body and mind.

GI: I also think about the process of archival work—there’s no end to it. You can become obsessed with chasing information that might be missing, or things you missed. But at the same time, through that work, you’re kind of missing all the beautiful moments that are in front of you. My daughter just turned one year old, and if I’m trying to chase down my past all the time, and talk about it over and over and over again, I miss out on all this new growth. So, when I think about that, this show, to me, is also a transformative point where I want to let go a little bit. I use myself, my family, my identity as inspiration, and I think it’s really important to honor these things, but I also don’t want it to become this overused conversation. Identity politics is very potent right now, especially during the pandemic, where people from all backgrounds are telling their stories.

But now I want to be able to use this institutional platform to say, “This is our story.” You see the full spectrum of my practice. You see the family ephemera. You see me putting myself in a vulnerable space to do my first transformative performance.

After this exhibition I’m excited to move onward like my grandparents and their parents did. I talked about this with my wife, and she’s like, “Let’s think about the future.” I mean, I could still be inspired by the past, but it doesn’t necessarily always have to be about that.

SB: So what do you have planned after this show?

GI: I have some exciting things coming up this year! A few group shows at the Long Beach Museum of Art – LMBA, Nicodim Gallery in Bucharest, and SPURS in Beijing. I also have some upcoming fairs to look forward to. But most of my energy is being directed toward Asia next year.

Greg Ito, Fire Watch, It Approaches, 2022, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 40 inch diameter [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles]

Greg Ito, All You Can Carry, Installation detail, 2022 [photo: Joshua Schaedel; courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and ICA San Diego]

Stephanie Bailey is editor in chief of Ocula magazine, a contributing editor at LEAP, and a regular contributor to Artforum International, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, and dɪ’van: A Journal of Accounts. Formerly the senior editor of Ibraaz, where she worked 2012–2017, Bailey is also a member of the Naked Punch editorial committee; a managing editor of Podium, the online journal for M+ in Hong Kong; and the current curator of Art Basel Conversations in Hong Kong.