“Golem Girl”: An Interview With Riva Lehrer

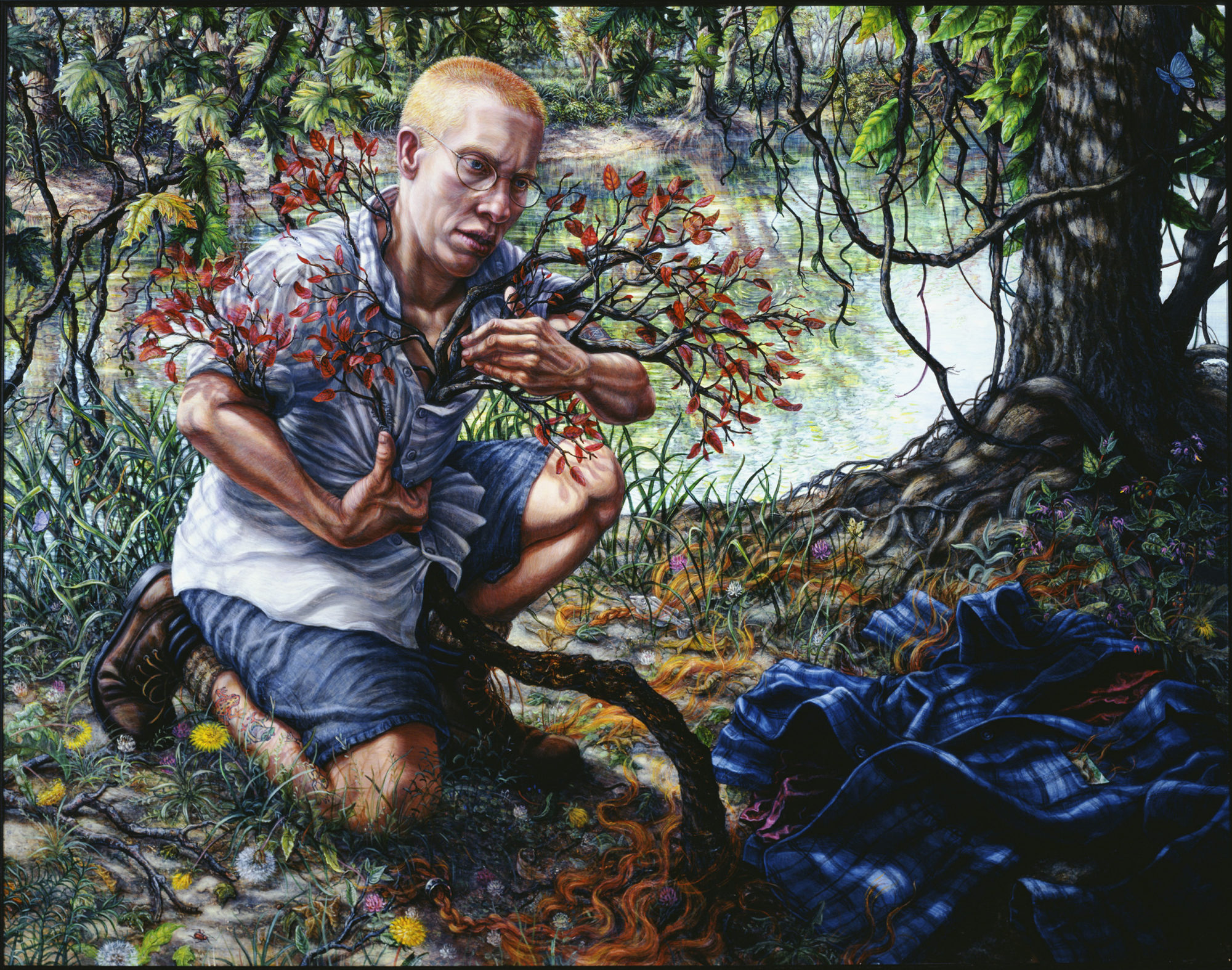

Riva Lehrer, Eli Clare, 2003, acrylic on panel, 29 x 37 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Emily Watlington: People might be familiar with your work [on] the cover of Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism or [on] Tobin Siebers’s Disability Theory. You’re also teaching in the Medical Humanities department at Northwestern. I’m curious about your relationship as an artist to this interdisciplinary academic realm.

Riva Lehrer: Yes, I’ve done a lot of book covers. I work with students a lot. When I was a student a million years ago, I had extremely little mentorship in terms of working with disability. Almost none. So I’m acutely aware of wanting to be that mentor for anyone who wants to work on—just embodiment, period. Even today, a lot of art schools address formal issues more comfortably than content, but the problems now are different. It used to be that content was roundly ignored, like embodiment. Now, people are very aware. So, where it used to be that a faculty member might not address embodiment because they didn’t think it was an important part of the conversation, now, anyone who is sort of in the progressive/left/theory field may be reluctant to engage because they’re afraid of getting it wrong, or of being offensive and not knowing where the parameters are. The effect can be the same in the long run: things are not getting hashed out, and there’s tension on both sides.

As an instructor, I try and engage as much as I can. I try to push people, and I tell them ahead of time that I’m going to get things wrong; that if I am getting things wrong, I want to be told; that we are all on a continuous learning curve. In the same way I’ve had to forgive people who have not been helpful to me but take what they could give me, I am hopeful that anyone I am working with can extend the same.

EW: Are you teaching mostly figure drawing?

RL: I teach various things over the years. Right now, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I’m a graduate advisor. At Northwestern, it’s not exactly a figure class. I work with medical students on drawing from the fetal collection. We don’t have a live model; we’re drawing from fetuses and jars. We’re talking about the idea of the historical disabled body and how to unhistoricize it.

Riva Lehrer, Brian Zimmerman, 2000, charcoal on paper, 18 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist]

EW: So, are the subjects of your portraits usually people you know from contexts like academia, or friends?

RL: Huge range. Sometimes I only know their work. Other people are longtime friends, colleagues in disability culture … it’s all over the map. I have someone coming on Sunday (I hope) who runs a small gallery nearby, and we’ve become friendly. Next week, I’m hoping to draw Achy Obejas, the novelist, who is coming in from California.

EW: What is your sitting process like?

RL: I have a few processes, though right now I’m really working on a book [Golem Girl, One World imprint of Penguin Random House, 2020], so I really haven’t been in the studio for a year, which has been really hard. Actually, one of the last people I drew was Lauren Berlant; she came and sat for several weeks.

I’m also working on a series of one or two day sittings; they’re very fast drawings. One of the last ones I did was of David Mitchell—not the disability studies David Mitchell, the British novelist who wrote Cloud Atlas. For this series called Risk Pictures, people come to my studio and sit on the couch and read; we talk and I draw. Then I give them the drawing for X amount of time, and ask them to alter it. When they bring it back to me, I work back into it. I’ve been doing this series for almost three years now.

For the extended series of sittings, each sitting is three hours, and at the two-hour mark, I walk out and give them control of my apartment. I tell them I’ll never ask what they do while I’m gone, though I know they’ve done … various things that I won’t get into! They have to alter their portrait while I’m gone. We go back and forth; they write on them, draw on them, erase things, add stuff. Then I come back and respond to what they did on the portrait, and we do that until it’s finished. But because I’m on book deadline, I’m not really doing extended portraits right now, just one or two day sittings.

Riva Lehrer, Neil Marcus: A Menorah for Gene Kelly, charcoal on paper, 2007 [courtesy of the artist]

EW: What’s your book about?

RL: It’s called Golem Girl, and it’s in two parts. The first part is about growing up as a disabled person in a time … before there was anything like disability rights. My mother became disabled when I was very young, so it’s also about being the disabled daughter of a disabled mother. The second part is about my discovery of, and being invited into, disability culture and starting to be a portrait artist who dealt with embodiment.

EW: Could you talk a bit about the politics of staring in your work? I’m thinking about how your work renders disabled bodies hypervisible while, at the same time, refuting representational tropes from things like freak shows or “inspiration porn.”

RL: I teach figure drawing, and I’ve read a lot of biology, anthropology. I understand why people stare. The theory is that we are social mammals, and we’ve evolved to be aware of difference within the group. Prey mammals look out for threats from the outside. Checking for “normalcy” within the group is a way of scanning for outside threats. All social mammals, whether prey or predator, have dominance patterns and submission patterns. We’re more like predator mammals who not only look for dominance patterns within their own groups, but also scan for weakness within the prey group. We are absolutely biologically constructed to scan for normalcy within our group, and what we perceive of as the “outside” tribe or species. We can’t help it.

The problem is the way that humans have socialized that imperative. Staring is not just somebody looking at you. We’ve evolved—or better, enculturated—this impulse to stare in a pejorative or negative way. It’s not just, “I’m looking at you”; I’m frowning, I’m hunching over, I’m looking at someone in a way that makes them not just feel that they are an object of interest, but that there is something wrong going on. There’s a difference between just the knitted eyebrows of, “This is interesting,” and the knitted eyebrows and down-turned mouth that people with visible anomalies tend to get. The issue is not being looked at; we are not going to end up in a society where people don’t look at each other, and we shouldn’t.

The way it used to be in New York—it’s not like this anymore—people would look at me because they seemed to find me interesting. They’d look away; it was a benign glance, if they even noticed me at all. Now, places like New York and San Francisco, where it used to be safe to be looked at, have become more conservative with the influx of money. There, I now get the midwestern glare: the pejorative stare. I’ve been places where I seem to be interesting and it’s not judgmental. But as our country becomes more conservative, there’s nowhere left where I experience that.

Riva Lehrer, Eli Clare, 2003, acrylic on panel, 29 x 37 inches [courtesy of the artist]

EW: Are there defining characteristics that distinguish an interested look from a judging one?

RL: It’s a conglomeration of rapid cues: small smiles … like when you pass somebody on the street that you kind of know and nod to them. Or when you pass someone who is wearing a fabulous garment and think, “Wow, that was really fun to see ….” People signal that. If you pass someone who looks dangerous or obtrusive in some way, there’s this flinching, a warning face: “Don’t get near me!”

In terms of staring within my work … in the beginning, it was more about trying to present people in a way that was not about titillation, but had a kind of “we’re all humans here” message. For that reason I really focused on what people produced: their writing or drawing. Bit by bit I tried to be … positive isn’t quite the word; without going into some kind of flattery. Disability is complicated: understatement of the century.

When people see images of people with disabilities, they often assume what I call “compensatory theory.” This may be slowly changing, but people often assume that even if it’s a positive image, what’s really going on is that the disabled person is in a state of suffering, that their life is tragic, and that even if they’re doing something joyful and happy, what we are seeing is an overcoming image. When we see an able-bodied person being happy, we don’t assume that they’re actually suffering, and that their happiness is a response to suffering. So, neutral up to joyous images of disabled people are read as compensation. There are similar conversations around images of queer people and people of color. You don’t have control over how an image is going to be read; you can have an intention, but it is often subverted by compensatory theory.

Riva Lehrer, Tekki Lomnicki, 1999, acrylic on panel, 48 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist]

EW: Clearly your works are responding to an absence as to who is traditionally represented in canonical, art historical portraiture. In that sense, it reminds me of Kehinde Wiley’s work, where he creates portraits of contemporary black figures in the language of art historical portraits for the elite. In addition to offering a critique of traditional portraiture, I’m wondering if there are other positive influences for you—artists whose work inspires you rather than those who you’re critiquing.

RL: Oh, sure, there are plenty. There’s Bailey Doogan, an early influence and [someone] who I studied with in Colorado many years ago. There’s Clarity Haynes and Sunaura Taylor. There are lots of contemporary portraitists whose work I love … particularly in African American culture. For me, Beverly McIver is much more compelling than Wiley; Titus Kaphar I absolutely adore. The problem with political portraiture is that when you have an image of somebody in a state of political pain, you risk turning the subject of the portrait into a symbol. This is the big problem with doing marginal portraiture. When you think of political portraiture, like those of Käthe Kollwitz or Charles White (whom I love), you have the problem of risking having the person stand in for an entire experience, an entire race, and to have the political point overshadow the specifics of the human depicted. There isn’t an easy answer for that one; even if I’m doing portraits where I’m trying to focus on the specific human, I know that if my work is still known a couple of decades from now, it can still be read as symbolic.

EW: One way you work against that is by depicting so many different people. In the context of reading all your work together, it’s hard to reduce it because there’s still so much breadth.

RL: That is specifically why I work in series. When I do a series, I’m usually bringing together people with disabilities, people from the queer community, able-bodied people … a whole range, and I ask that group the same question. My series, like Totems and Familiars, should be read as one coherent investigation.

Riva Lehrer, Susan Nussbaum, 1998, acrylic on panel, 16 x 26 inches [courtesy of the artist]lvinar dapibus leo.

EW: I wanted to ask if you’ve ever made, or thought about making, a portrait of someone with invisible disabilities. I’m curious as to how you might represent that—or choose not to.

RL: I have. If the person I’m working with does not want to disclose, then I can’t either. I’ve done several portraits of people with nonapparent disabilities—I would prefer nonapparent to invisible, sometimes I use unvisible—but the problem is that when you try and depict nonapparent disabilities, there are such horrible tropes around it. Especially mental illness disabilities: you get this history of demons, auras, and hallucinations …. It’s very hard to symbolically depict them. Similarly, I’m thinking about pain a lot these days, about how one can depict pain without reifying the trope that disability is a painful state. The trope makes a huge aspect of the reality of disability extremely hard to address.

EW: Jasbir Puar’s book The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability gets at this, too, trying to reconcile disability pride with hatred for state violence and, subsequently, its disabling effects, while showing how disability is produced unequally across race and class.

RL: I completely agree with that. I’m also thinking a lot about aesthetics, and how they have gotten left out of the conversation a lot. We talk about them in terms of how to read a work, but not so much regarding how to produce a work.

EW: That’s been on my mind also, especially when curating works of historic video art. It would be considered a conservation taboo and aesthetic affront to put closed captions on them … but a lot of early uses of video were precisely aimed at radical accessibility. If they were shown on TV today (as many originally were), they would, by law, have a captioning option. So I’m thinking about this aesthetic distaste, and who it privileges.

RL: That’s part of it, aesthetics and accessibility. But then there’s the question of, what is beauty in disability? What is enjoyment? Not just in the disabled body, but the world. If we are in a continuous state of assessment of all things in terms of whether or not they’re “accessible,” what kind of aesthetic does that actually construct? I don’t have an answer for that yet, but I’m thinking about it.

This conversation originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.

Riva Lehrer is an artist, writer, and curator whose work focuses on issues of physical identity and the socially challenged body. She is best known for representations of people with impairments, and those whose sexuality or gender identity have long been stigmatized.

Emily Watlington is a critic, curator, and 2018–2019 Fulbright scholar based in Berlin, Germany, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.