Erotics of the Image

Share:

A couple of years ago, while presenting the work of a straight female artist in Artforum,1 I discussed some of her projects in relation to lesbian cultural practices and gender theory, and, in one piece, her exploration of male homoeroticism. This effort was rewarded by an (unpublished) letter ot the editor from a lesbian artist claiming that, in so doing, my own work was “supportive of the cultural mandate of lesbian invisibility.” That the letter’s author was someone I had once been close friends with, and whose work I had frequently written on in the past, made its attack more poignant.

At the time, my response was pretty philosophical: people who believe in the autonomy and authenticity of lesbian identity do take their beliefs very seriously. My lover, more humorously, suggested we make stickers and T-shirts proudly proclaiming “Lesbian Invisibility Now!” Just the thing to put up next to those annoying “vaginal pride” stickers in the bathrooms at school.

However, in wishing to reassert clear boundaries between gay and straight sexualities and identities, this letter writer is clearly not alone. And for many lesbians, it may indeed seem that the only avenue to viable cultural visibility is to claim the immediacy and primacy of one’s gender, sexuality, and “authentic identity.” To context or question such claims is seen, in a performative sense, as depriving women of them; any argument for ambivalence or ambiguity, any investigation of our inevitable implication in the structures that oppress us, is seen simply as complicity with them.

But really, what would it mean to consider lesbian visual production as not necessarily anchored in a notion of the authentic lesbian subject, the authentic female body? What would that look life? And would such choices rally doom lesbian artists to complete cultural invisibility? Perhaps we should also consider what covert prescriptions may lurk behind certain liberationist claims for lesbian visibility. Is sexual and bodily representation in lesbian art really so direct and unproblematic? And must all “lesbian art” now be about the body, and the female body at that?

I want to consider what counts as “lesbian” in the visual field, through looking at work that involves a kind of libidinal displacement—one that the conceptual artist Lutz Bacher has termed “the erotics of the surrogate image.” At times, this surrogacy may take the form of imaging male bodies—male bodies that sometimes, I will argue, function as substitutes or stand-ins for the female body. We may be all too familiar with representations of the female body that, ultimately, speak male longing, anxiety and desire, but we are less used to the reverse: a male body that speaks female fears and desires, particularly lesbian ones. Yet such is the case in Monica Majoli’s series of gay male S/M scenes, painted in 1990 and 1991.

These small canvases—the originals are about 12” x 12”—look like Renaissance devotional paintings. Majoli tells us that they were made in dialogue with a gay male friend: he told her stories, which she then translated into highly-orchestrated tableaux.2 These canvases could be seen as a rather morbid project if subcultural documentation: lesbian artist recording gay male friend’s sexual adventures, presumably in the past tense. And in their darkness and melancholy, they are indeed works which are in some sense “about” AIDS, about disappearing gay lives and gay ways of life. So we can read them as memorials: painting, as many have noted, often carries the task of mourning.3

But seeing them only as memorials effectively erases Majoli, the lesbian artist, and her desires. What is her relation to these men? In a recent article in Art Issues, the LA-based writer Susan Kandel has suggested that by masking her lesbian identity under the guise of the gay male figure, Majoli performs a kind of inauthenticity. Kandel suggests: “Majoli’s flowing images take an unexpected turn. They proclaim eros as transcendence, but evince little jot. They are dark, tightly wound, strangely suffocating. Perhaps this is because the paintings also camouflage Majoli’s own lesbian desires. This she mimes in a masculine mode.”4

Kandel goes on to suggest the dangers of such miming: the loss of identity, the collapse of the body into its surroundings. And clearly there is a way in which lesbian artist appearing to image gay male desire does risk a certain loss of identity—a particularly acute risk given the lure of being taken up in the circuits of gay male art collecting and exhibiting. Doesn’t this just repeat the position of the woman exchanged between two men—a new kind of heterosexuality re-enacted among the literally homosexual?

Yet is that what is really going on here? Look at the bodies: many of the male figures are oddly feminized; some have curiously soft torsos, suggesting female contours. If Michelangelo painted his female figures simply be rendering men with breasts, Majoli seems almost to do the reverse. Tight, obsessive, and technically masterful, the small canvases evoke a sense of forbidden obsessions, and a world in which the painter herself is completely absent. But is she? Majoli has stated that the stories resonated with her because “what these men were doing was how I had sometimes felt with women, that sense of erotic torture, of suffocation.” Besides offering psychic substitutes for her own lived sense of masochism, the men also represented figures of desire for Majoli—”working on the paintings was a way to work out my feelings about men, about the male body—as well as a locus of identification: “I am that man in the bathtub. He is me.”

What would Majoli’s lesbian sex painting look like? The example Kandel prefers, of two women on a bed, acting out fellatio with a dildo, is one option. Yet this image doesn’t quite work for me—it seems too literal, too direct in its presentation of lesbian sex. Where I find Majoli’s lesbian desires more powerfully imaged is in her series of body fragment self-portraits: luminous erotic paintings where the sexual merges, as it so often does, with narcissism. The images of a scratched and bleeding wrist, the first of the series, came to Majoli accidentally after a cat scratch. The painting probes the ambiguity of the marks: are they sexual wounds, stigmata, the results of a half-hearted suicide attempt? In each image, there is a nagging sense of abjection alongside the beauty.

Perhaps wary of highly romanticized representations of lesbian desire, Majoli works through the fragment—a structure of fetishism, to be sure, but one that can also register as violence or dismemberment. Yet what is “sex” here becomes more enigmatic; rather than localized in certain acts, certain parts of the body, a clearly depicted narrative or scene, it seems diffused along the body. In other paintings, the images of skin are so close up they become abstract: through them Majoli explores the ambiguity of bodily representations, the indeterminacy of meanings, the projections of the viewer.

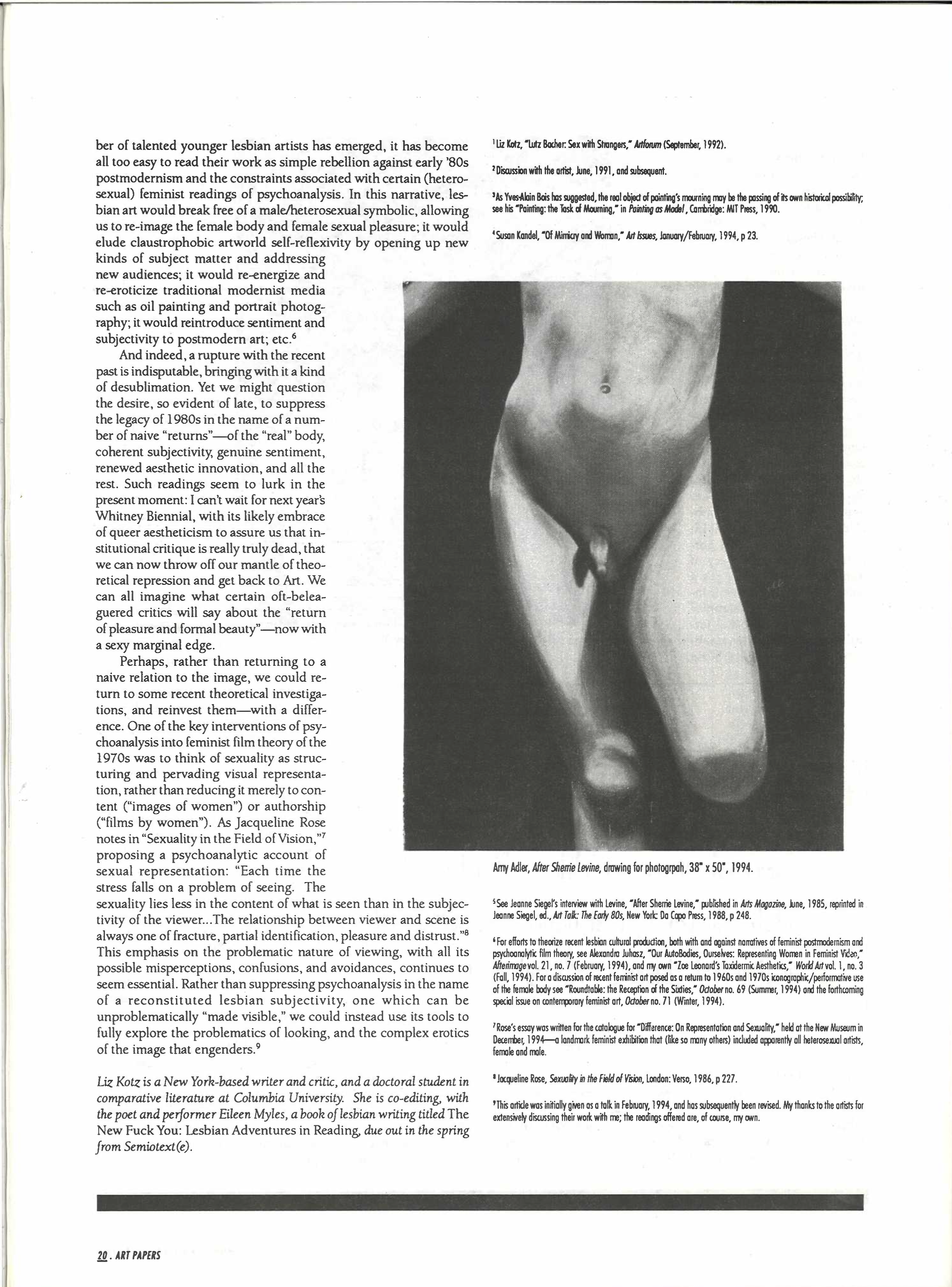

Majoli’s use of the male body as surrogate is echoes in a series of recent projects by another Los Angeles-based artist, Amy Adler. Adler’s photographs use appropriated images, but she submits them to an intermediary stage as drawings, introducing a highly personalized third term between photographic “original” and “copy.” In After Sherrie Levine (1994), Adler presents a large charcoal drawing of one of Levin’s Untitled (After Edward Weston) photographs. The image (originally of Weston’s son Neil) is of a young male torso shot from the chest down; Adler subsequently photographed the drawing, producing a series of small (8 x 10) prints. There’s something uncanny about the doubled-back nature of this process: making a drawing derived from a photograph, and then photographing it. Something muffled and disguised, which speaks, indirectly, about the suppressed erotics of the image: a nubile young boy posed for our pleasure, a transaction between father and son, artist and viewer, original and copy.

Adler’s own “copy” is incongruously distanced, displaced, and very, very intimate. By physically handling, touching, and meticulously drawing the boy’s body, she puts herself in a more proximate relation to him. Is she the nubile young figure, the object of potentially incestuous desire? Or the onlooker, masking lust under the alibi of Art? After Sherrie Levine hinges on photography’s capacity to distance these positions and make them slippery, reversible. Yet the return to drawing re-emphasizes the image’s sexual side, desublimating an erotics that has been persistently repressed in critical readings of Levine’s work. This relation between the artist and her borrowed image, Levine has insisted, is not merely a critique of male authorship, but a displaced erotics that must be mediated through a third term: “My work is so much about desire and its triangular nature. Desire is always mediated through someone else’s desire.”5

As Adler models her piece on Levine’s celebrated image, she establishes her own perversely triangulated relation to postmodern photography: desiring Levine desiring Weston desiring Neil? Focusing on the erotics of this intermediary third term, Adler’s oddly mediated method mirrors the twisted, displaced workings of desire: the substitute that both replaces and displaces the lost object, the libidinal repudiations and reversals that only produce an unending return of the repressed. At the same time, by probing the ambiguous transactions between the photograph and the drawn image, Adler’s work echoes back on Majoli’s use of photographs to paint her scenes—reminding us of the mutual implication of painting and photography, a historical transaction that dates back to the 19th century.

In The Team (1994), Adler presents a series of nine photographs of charcoal drawings. These feature male baseball players, whose faces were copies from small catalogue-like photographs in the back of sports magazines. Perversely repressing the sensuously handmade drawings, Adler exhibits only the more impersonal, more homogenized photographic copies. It’s as if each player has a hidden double, a ghost, that is persistently excluded. The black and white drawings are vaguely threatening, oddly sexy; there is nothing to mark them as “lesbian.” Yet the doubled-back process of production suggests that we are being let in on a private world of fantasy, a psychic place where many desires converge: looking and wanting, danger, displaced self-representation, evil twin, “I can be that boy for you.”

In a linked project, Gold, Adler made a series of three pastel-colored drawings of angelic young men, taken form the pages teen magazines: a fantasy landscape of perfect boy youth. In their gold-tinted prints, the pretty, feminized boys echo an iconography of gay porn; the images also bring to mind Richard Hawkin’s use of fan magazine photos of male stars in some of his art objects. Yet in Adler’s work, there’s some kind of distance from pornographic or completely camp representation of boys; after all, she’s not doing Keanu Reeves. The work is not about something so libidinally straightforward and direct as reading a gay (male) subtext in idealized pop representations; instead, it takes up the murky position of a woman locating herself in these circuits of desire, and doing so as a lesbian.

Catherine Opie’s work presents a different project, one that also uses photography to get at some of the destabilizing vicissitudes of sex and gender. Last year Opie exhibited her series “Being and Having” in New York: 24 color portraits of young women dressed up as male street toughs, engaged in sometimes convincing, sometimes utterly artificial, form of cross-gender drag. Subsequently, she turned to other, perhaps more serious forms of sexual self-fashioning. Women she knew, long-time friends from the leather community in San Francisco, were taking hormones and turning into “men,” choosing to live in the world as men whether or not they had undergone surgery—most hadn’t. The artist wasn’t sure how she felt about this: is it an escape from oppression or a betrayal when lesbians “become” men? She wanted to honor her friendships and her community, yet also explore this ambivalent terrain.

A series of portraits ensued, mostly taken in the San Francisco gay and leather communities. What is intriguing and unsetting about the images is that they don’t tell you exactly what you’re seeing. In both Mike and Sky (1993), there is nothing to announce that these are pictures of lesbians taking male hormones; there is a suggested swelling of the shirt, but nothing more. So the viewer is left in a certain ambiguity, on which gets lost in the speedy “rush to the signified” that animates many critical readings—making the photographs “about” female transsexuals, S/M, the leather community, etc. Where such unease or ambiguity is diminished, as in the portraits of tattooed and pierced subjects and subcultural celebrities, the pictures become more pedestrian; without the capacity to disturb and unsettle, they verge close to fashion photography, albeit in a subcultural vein.

Two images of the most recent work strike me as most challenging, most difficult. One is a self-portrait called Cutting (1993): a happy domestic scene, two stick-figure girls holding hands in front of a house, a scene cut by a friend into the artist’s back. It is not an easy image to look at, but one can relate to the inseparability of pain and longing, transcendent pleasure and presence, it embodies: this is writing on the body in its most literal sense. Another image is of Opie’s friend, Darryl, with multiple cuttings on his back. The cutting has been done over a long time. They are decorative and oddly beautiful; some scars are old, dark and covered over, others fresh, new and pink. What does it mean for a black American man to engage in such cutting—an act that evokes whipping and ritual scarification, a complex response to a history of abuse and survival? And what is Opie’s relation to this figure, her desire in and for him, her probable identification with him? Do we simply consign these portraits to the uneasy legacy of Robert Mapplethorpe? It’s a pointed question, since it is indeed in relation to Mapplethorpe’s legacy—beautiful formalist prints of subcultural subjects—that Opie’s work is being taken up in the NYC artworld.

What provisional generalizations could we make about these artists’ quite heterogenous work—and perhaps that of some other lesbian artists as well? It’s very engaged with sexuality, but often in a distanced form, no longer localized in gender or specific sexual identities: it’s sex as diffused along the body and the skin, for instance, or as read across other scenes—heterosexual or gay male. It’s aggressive, sometimes violent, and unwilling to anchor these images within the terms of an explicitly-articulated “critique”; there’s no context, no artist’s statement, and a refusal to read and hence “frame” these images for the viewer. An in addition, it’s work engaging with the repressed, sensual side of artmaking, whether taking up painting as the ultimate “bad object,” or leaving aside activist traditions of photo-text to return to sumptuous formalist photography. It’s also work that’s very invest in male lineages of art.

Linking these projects, however disparate, is the refusal of a set of framing strategies that predominated in much 1980s feminist art. Re-emphasizing the indeterminacy of the image—where the viewer doesn’t know exactly what she or he is seeing, or what it means—seems key to reopening the circuits of libidinal investment in and around the image. Of course, critics might argue that. By abandoning the kind of contestatory voice that implicitly addresses the straight male viewer, and by paradoxically adopting the male body as psychic substitute and problematic site of desire, these artists disguise and disperse their own lesbian subjectivities. Yet in so doing, their work refuses a kind of containment and reduction; there’s always something a little seamy, twisted or abject to remove them from a more direct, celebratory project of mainstream identity politics. If lesbian desire in this work is mostly subliminal, it is not unreadable.

Why would it be important, right now, to defend such ambiguity and indeterminacy? Why might I counterpose, to an agenda straightforward, “in your face” lesbian representation, an alternate erotics of surrogacy and displacement? There is no question that we are in a period of intense commodification of identity, with an attendant demand for extremely reductive and normalizing approaches to image-making. As a number of talented younger lesbian artists has emerged, it has become all too easy to read their work as simple rebellion against early ‘80s postmodernism and the constraints associated with certain (heterosexual) feminist readings of psychoanalysis. In this narrative, lesbian art would break free of male/heterosexual symbolic, allowing us to re-image the female body and female sexual pleasure; it would elude claustrophobic artworld self-reflexivity by opening up new kinds of subject matter and addressing new audiences; it would re-energize and re-eroticize traditional modernist media such as oil painting and portrait photography; it would reintroduce sentiment and subjectivity to postmodern art; etc.6

And indeed, a rupture with the recent past is indisputable, bringing with it a kind of desublimation. Yet we might question the desire, so evident of late, to suppress the legacy of 1980s in the name of a number of naïve “returns”—the “real” body, coherent subjectivity, genuine sentiment, renewed aesthetic innovation, and all the rest. Such readings seem to lurk in the present moment: I can’t wait for next year’s Whitney Biennial, with its likely embrace of queer aestheticism to assure us that institutional critique is really truly dead, that we can now throw off our mantle of theoretical repression and get back to Art. We can all imagine what certain oft-beleaguered critics will say about the “return of pleasure and formal beauty”—now with a sexy marginal edge.

Perhaps, rather than returning to a naïve relation to the image, we could return to some recent theoretical investigations, and reinvest them—with a difference. One of the key interventions of psychoanalysis into feminist film theory of the 1970s was to think of sexuality as structuring and pervading visual representation, rather than reducing it merely to content (“images of women”) or authorship (“films by women”). As Jacqueline Rose notes in “Sexuality in the Field of Vision,”7 proposing a psychoanalytic account of sexual representation: “Each time the stress falls on a problem of seeing. The sexuality lies less in the content of what is seen than in the subjectivity of the viewer…The relationship between viewer and scene is always one of fracture, partial identification, pleasure and distrust.”8 This emphasis on the problematic nature of viewing, with all its possible misperceptions, confusions, and avoidances, continues to seem essential. Rather than suppressing psychoanalysis in the name of a reconstituted lesbian subjectivity, one which can be unproblematically “made visible,” we could instead use its tools to fully explore the problematics of looking, and the complex erotics of the image that engenders.9

Liz Kotz is a New York-based writer and critic, and a doctoral student in comparative literature at Columbia University. She is co-editing, with the poet and performer Eileen Myles, a book of lesbian writing titled The New Fuck You: Lesbian Adventures in Reading, due out in the spring from Semiotext(e).

References

| ↑1 | Liz Kotz, “Lutz Bocher: Sex with Strangers,” Artforum (September, 1992). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Discussion with the artist, June, 1991, and the subsequent. |

| ↑3 | As Yves-Alain Bois has suggested, the real object of painting’s mourning may be the passing of its own historical possibility; see his “Painting: the Task of Mourning,” in Painting as Model, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990. |

| ↑4 | Susan Kandel, “Of Mimicry and Woman,” Art Issues, January/February, 1994, p 23. |

| ↑5 | See Jeanne Siegel’s interview with Levine, “After Sherrie Levine,” published in Arts Magazine, June, 1985, reprinted in Jeanne Siegel, ed., Art Talk: The Early 80s, New York: Da Capo Press, 1988, p 248. |

| ↑6 | For efforts to theorize recent lesbian cultural production, both with and against narratives of postmodernism and psychoanalytic film theory, see Alexandra Juhasz, “Our AutoBodies, Ourselves: Representing Women in Feminist Video,” Afterimage vol. 21, no. 7 (February, 1994), and my own “Zoe Leonard’s Taxidermic Aesthetics,” World Art vo. 1, no. 3 (Fall, 1994). For a discussion of recent feminist art posed as a return to 1960s and 1970s iconographic/performative use of the female body see “Roundtable: the Reception of the Sixties,” October no. 69 (Summer, 1994) and the forthcoming special issue on contemporary feminist art, October no. 71 (Winter, 1994). |

| ↑7 | Rose’s essay was written for the catalogue for “Difference: On Representation and Sexuality,” held at the New Museum in December, 1994—a landmark feminist exhibition that (like so many others) included apparently all heterosexual artists, female and male. |

| ↑8 | Jacqueline Rose, Sexuality in the Field of Vision, London: Verso, 1986, p 277. |

| ↑9 | This article was initially given as a talk in February, 1994, and has subsequently been revised. My thanks to the artists for extensively discussing their work with me; the readings offered are, of course, my own. |