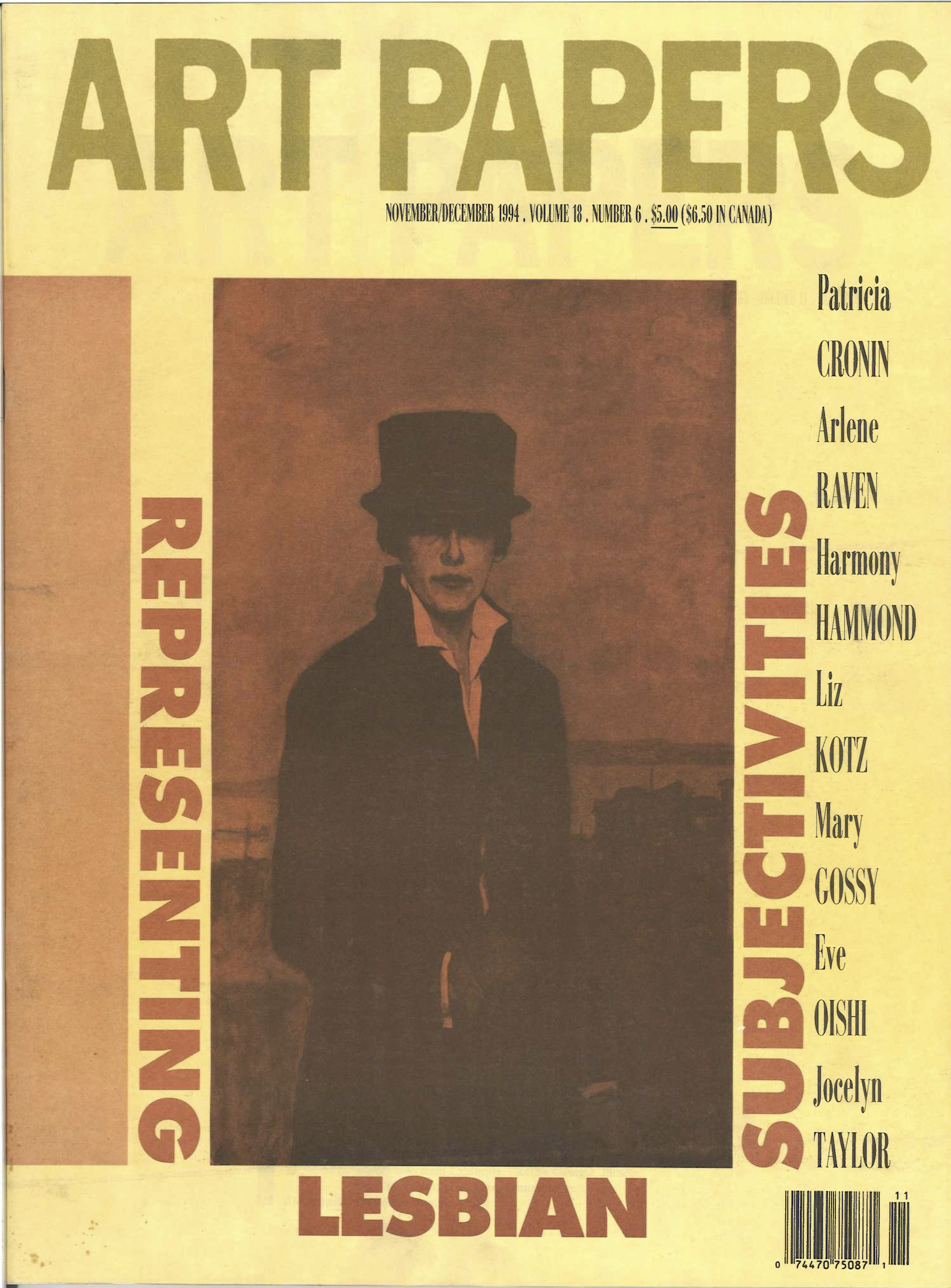

Representing Lesbian Subjectivities

ART PAPERS November/December 1994—Representing Lesbian Subjectivities—guest edited by artist Patricia Cronin, features essays originally written for Representing Lesbian Subjectivity, a symposium she organized at the Drawing Center in New York on February 12, 1994. “Lesbian Subjectivity” was changed to “Lesbian Subjectivies” to better encompass converging identities as essential to the study of “lesbian contemporary art.”

When I was invited to write this introduction, I was asked if the word lesbian felt anachronistic. Invisibility has a lot to do with this question, which is a complex one that requires us to locate what lesbian means; how, why, and when it’s used; and how its meaning continuously shifts. Lesbian has always been intertwined with activist and radical spaces, as an identity that can never be singular or ahistorical. Lesbian inherently connotes an assemblage of subjectivities, which emerges, at times, in arguments about what constitutes the “authentic” lesbian subject. These conflicts appear throughout the issue in question and persist today as lesbian tasks itself with being a battleground for debates central to sexuality and gender.

Womanhouse and other art-activist spaces of the 1970s were featured in Arlene Raven’s essay “Los Angeles Lesbian Arts,” which defined “any work made by a woman-identified woman [as] lesbian art.” Raven discusses these infamous feminist art spaces and the work that lesbians did to “come out” within them—a perspective that went from that “of an outsider to one of belonging.” This text is followed by Harmony Hammond’s polemic “Cultural Amnesia,” which states, “Everyone, including lesbians, is acting like the 70s didn’t happen.” Hammond casts lesbian artists working in the 1990s as art market darlings who abandoned their herstory. A lot of evidence suggests otherwise, but she makes a compelling advocation for context within an established lineage of lesbian/gay/queer aesthetics to establish power in the arts. The exhibition Images on which to build, 1970s-1990s [March 10–July 30, 2023] at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art does an excellent job of illustrating this point: Being lesbian is contextual.

Lesbians making art in the 1990s centered the erotic as a mode of constructing identity. “Uses of the Erotic: Sexuality and Difference in Lesbian Film and Video” by Eve Oishi focuses upon film and video created by lesbians of color. Oishi meditates upon Audre Lorde on race, class, and difference within the lesbian community, and how, in the United States, sexuality and race cannot be separated. She writes about white feminist movements that sought to suppress racial difference, and that this difference is the source of the erotic.

In “Erotics of the Image,” Liz Kotz asks who gets to make lesbian art? Is the authenticity of the subject necessary for combating lesbian invisibility, or does the construction of an “authentic subject” fuel it? Who has the authority to define the authentic lesbian subject? Kotz writes about Monica Majoli, Amy Adler, and Catherine Opie, subversive sexualities, and transmasculine identities. Kotz’s grappling with Opie’s portraiture of her transmasculine friends now reads as outdated. However, what’s clear is that lesbian was a space where gender and subversive sex were played with, discussed, debated, and reborn. What hurts me the most in the issue is the lack of lesbian-identified transwomen, which recalls specific and painful exclusionary moments in lesbian history, and which exists in sharp contrast to my own lesbian community in New York.

Mary Gossy reorients Barbie to be a lesbian object in “Gals and Dolls: Playing with Some Lesbian Pornography.” She writes about a series of erotic images involving the Barbie doll that were published in the notorious lesbian magazine On Our Backs. She speaks of magic, of a lesbian putting a Barbie inside her cunt as ecstatic performance of desire. Lesbian porn, here, is a balm to patriarchal violence and a salient method to define the lesbian subject. With the new Barbie movie forthcoming, I found this essay delightfully perverse, psychoanalytic, and experimental.

The features conclude with Jocelyn Taylor’s raw “I Seek to Steal the Sexual Body,” in which she discusses the politics of her own filmmaking. The text ends with Taylor showing her mother some of the erotica she produced. Her mother’s nonchalant response to it is a sweet, funny end to this collection of hard-hitting essays. Reviews of Judie Bamber’s vulva paintings, filmmaker and artist Beth B, and Amalia Amaki and Liz Hampton at the Tula Women’s Gallery accompany these features to give us a taste of what exhibitions were up at the time. And because the lesbian art community is so close knit, Judie and I had dinner in Los Angeles last week.

Digitizing these materials and making them accessible to artists, scholars, and budding sapphic-art-herstorians is deeply important now, during another time when erasure of sexual identity/desire and an assault on bodily autonomy are gripping the United States. While working with this material, I realized my reading of it was based upon my own subjectivities—my identity as a lesbian, former sex worker, dyke, artist and writer, and upon my experiences in the lesbian/queer/trans art and literary communities in New York. The powerful relational aspect in reading and working with this material is one that I am thrilled to share with ART PAPERS readers online.

— Jillian McManemin

Share:

Judie Bamber

Amalia Amaki/Liz Hampton

Arrested Childhood

Maria Artemis and Eleanor Hovda: Labyrinths

Uses of the Erotic: Sexuality and Difference in Lesbian Film and Video

Erotics of the Image

Why would it be important, right now, to defend such ambiguity and indeterminacy? Why might I counterpose, to an agenda straightforward, “in your face” lesbian representation, an alternate erotics of surrogacy and displacement? There is no question that we are in a period of intense commodification of identity, with an attendant demand for extremely reductive and normalizing approaches to image-making.