Art Isn’t Neutral

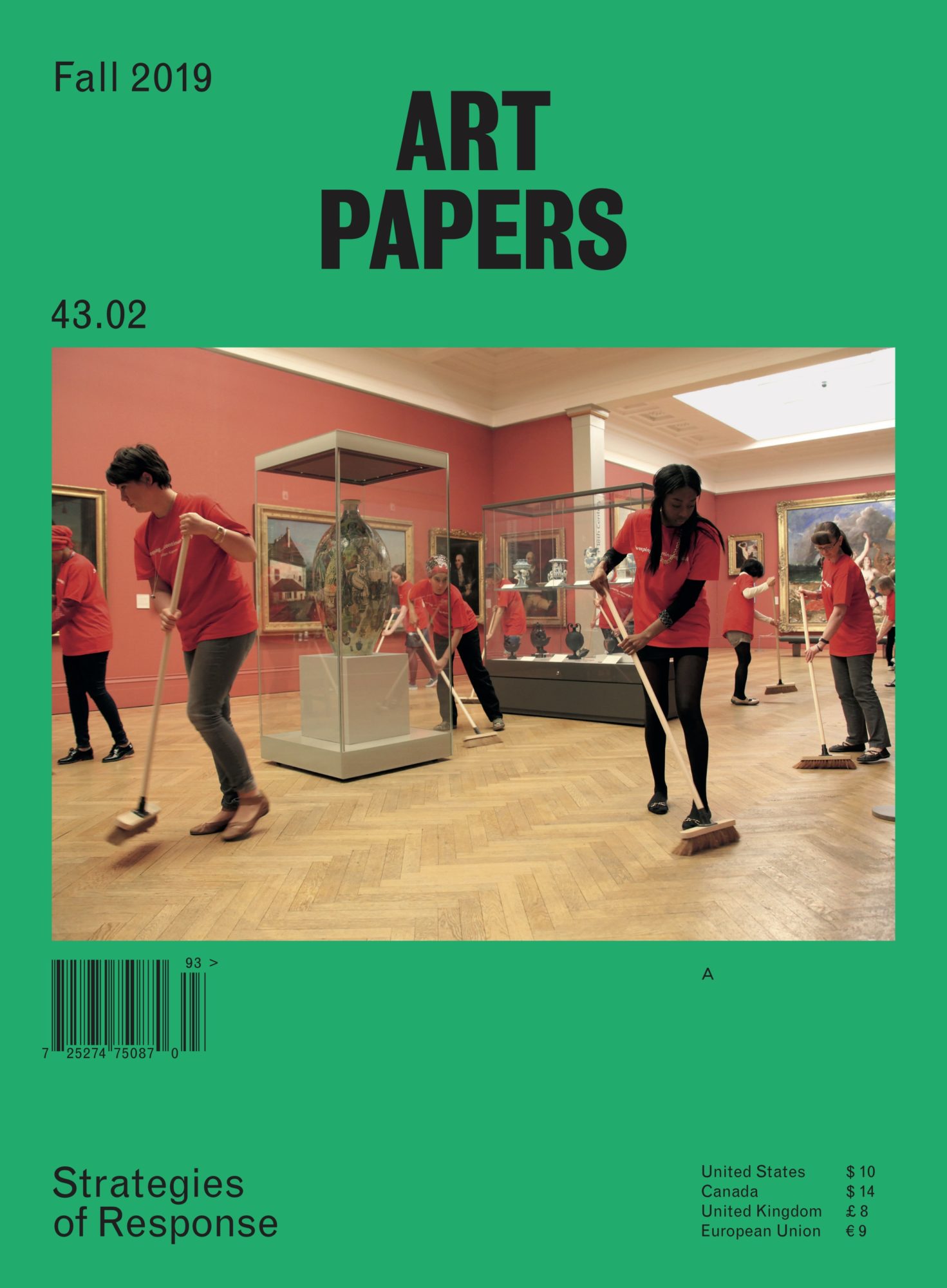

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art, 2016-2017, installation view [photo: Hai Zhang; courtesy of the Queens Museum]

Share:

I came across the work of Carin Kuoni and Laura Raicovich while in search of art workers who are holding cultural institutions accountable for unethical investments, associations, and labor practices. They are the co-editors, with Kareem Estefan, of Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production (OR Books, 2017). At the moment, they are directors of the seminar series Freedom of Speech: A Curriculum for Studies Into Darkness, which is organized by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics as part of the center’s 2018–2020 curatorial focus If Art Is Politics. Kuoni is director/chief curator of the Vera List Center; Raicovich is a writer and curator who was president and executive director of the Queens Museum until January 2018. She is currently the inaugural Emily H. Tremain Journalism Fellow for Curators at Hyperallergic. In this interview Kuoni and Raicovich provide numerous reasons that art is politics. They explain the myth of neutrality and provide insight into their work together.

Sara Wintz: I always think of curators as the people responsible for organizing precious objects. The work that you do as curators is organizing people. What’s the difference?

Laura Raicovich: I’ve always preferred the phrase, “organized by.” After I left the Queens Museum, people questioned why I favor the term “art worker” rather than “curator.” I’m not a curator in a traditional sense.

Carin Kuoni: For me, the most valuable aspect of curating—and the most delicate moment—is when people come together in public. All the work goes into making that a safe space and a respectful space and productive space, it means we’re not concerned with shipping art, but we are concerned about the relationships we build with audiences, with partner organizations, with staff.

LR: Who are we encouraging to attend this program? What kind of registers does it have to hit in order to extend beyond the typical audience?

CK: I’m particularly interested in the subject of freedom of speech or speech acts when we go beyond words, communication, language. It’s ultimately about bodies in space. That’s what we are trying to be very mindful of and respect.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art, 2016-2017, installation view [photo: Hai Zhang; courtesy of the Queens Museum]

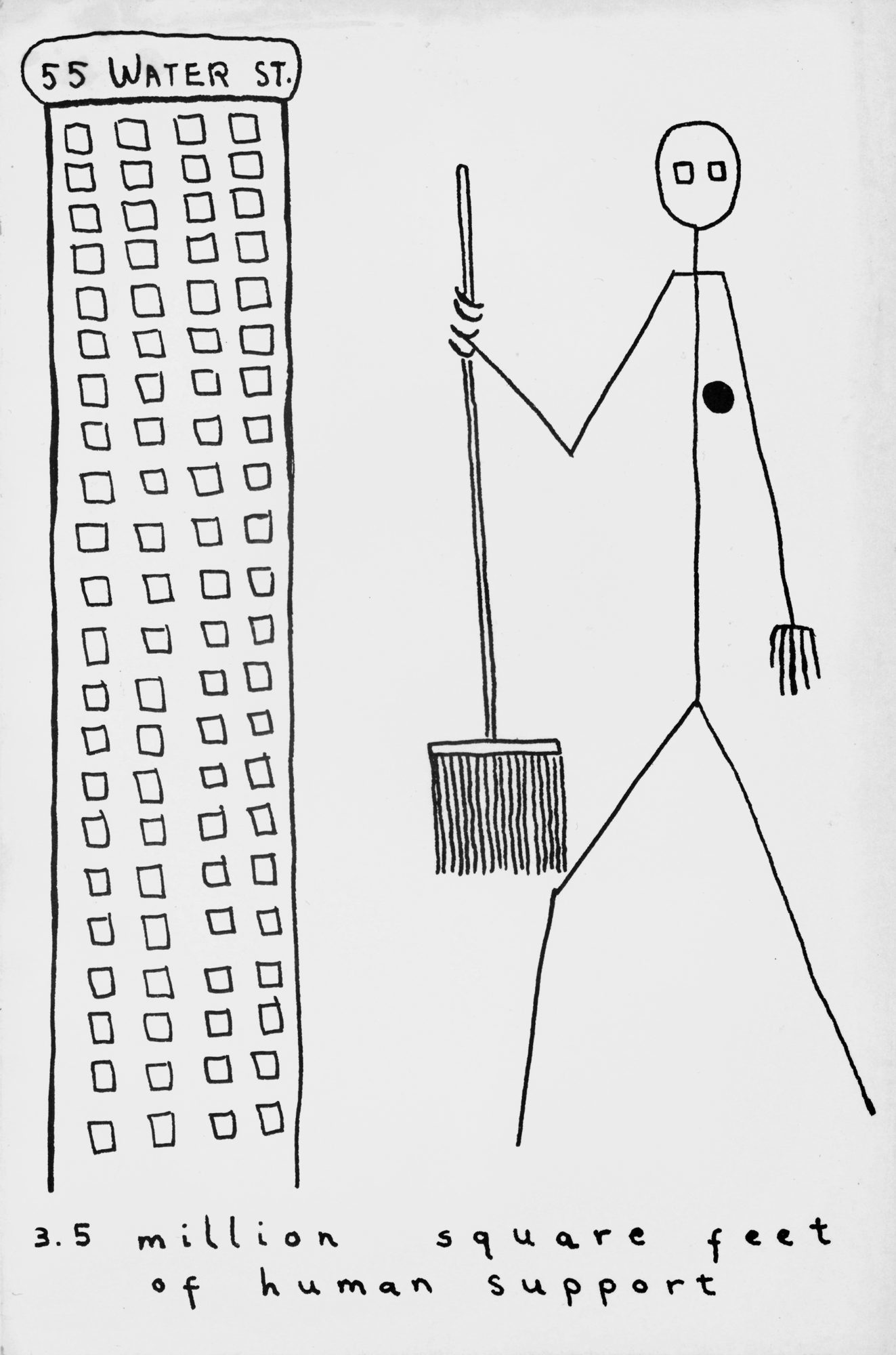

SW: As women, we’re advised to “lean in” and take up space in order to gain power. Laura, you’ve written about Mierle Laderman Ukeles. How much of your practice is inspired by feminist interventions that happened in the 1970s and 1980s, by [such artists as] Linda Montano, Mierle Ukeles, Suzanne Lacy-who repositioned the attention that previously went to the artist, onto the world around them? Who informs and inspires your work?

LR: Certainly Mierle. There are so many different feminisms that we need to be attuned to, and I’ve been trying to open my own brain to the thinking of black feminism and Indigenous feminism and other feminisms that my education didn’t center because they were not prioritized in white educational spaces.

CK: My situation is very different: I grew up in Switzerland, where women acquired the right to vote in the 1970s. My formative encounter with an artist or an artist’s practice was with Joseph Beuys and his social sculpture. Beuys is a figure I can’t let go of, despite various reservations. When I arrived here, this notion of art as social sculpture is what I brought with me. I was a co-founder of an artist collective called REPOhistory, a name that stands for “Repossessing History.” And that’s what we tried to do: inscribe into the urban fabric of New York City different histories, histories that had not yet been told. The idea that you’re continuously re-creating and re-articulating a history that needs to be made visible, that’s where I come from.

LR: My collegiate years were so formative. I studied art and political science as an undergraduate. My thesis advisor had organized farm workers. She had worked with Cesar Chavez, and her students helped organize the mushroom workers around Philadelphia, who had terrible working conditions in the early 90s. And of course, this was also a period of feminist activism as well, with regular “Take Back the Night” marches.

As I made my way in New York, I worked at public art organizations [such as] Public Art Fund, and then the Guggenheim. In 2001 I ended up at Dia, which was an incredible place to be because of its focus on the needs of the art and the artists we worked with. After 10 years, I began to miss the social activism piece of it. I kept feeling this urgency, particularly in the context of what was happening politically, to connect art to life in more direct ways. I’ve always believed art has the true capacity to make change.

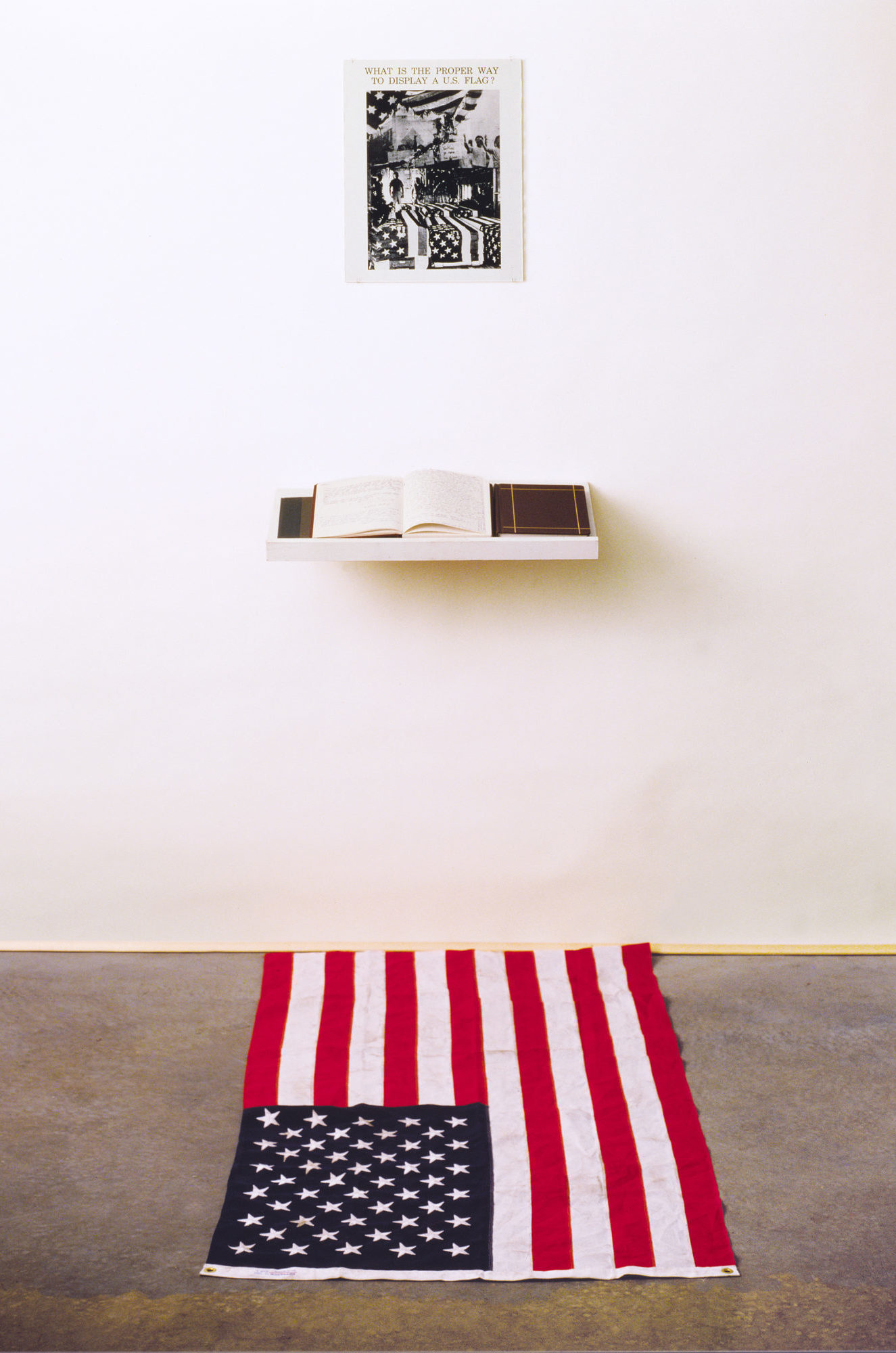

For example, Dread Scott is an artist whose work I admire. He made headlines really early in his career as an undergraduate at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. He created a work that forced its viewers to decide whether to step on an American flag in order to engage with it. The work was branded as “disgraceful” by US President George H.W. Bush and the US Congress, and subsequently became part of a landmark Supreme Court First Amendment ruling. There are so many circumstances in which a work like that will move people.

Dread Scott, What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag?, 1988 [courtesy of the artist ©Dread Scott]

SW: Not necessarily taking a hard line, but inviting people to participate or to experience something in a different way?

LR: Or to see the world in a slightly different light that might change the way you decide to approach an issue.

CK: I’m thinking of Gulf Labor, the artists’ coalition that has called for a boycott of the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi. They not only did that, they also provided platforms for artistic interventions into the concept of creating a modernist museum in the Gulf, based on labor conditions that would be unacceptable in our society. Rather than just call for a boycott, the artists of Gulf Labor in various artist interventions, many online, articulated potential alternatives. That approach is a really important part of our thinking about boycotts—not only withdrawal or refusal, but an opening through art of different ways to engage with issues. Not avoiding them, but approaching them differently.

LR: That’s why we called the series of seminars, and the book, Assuming Boycott, because we have to accept that boycotts happen in the world, and it’s more how we respond to them and what we do about them that matters, [rather] than the fact that they exist or don’t exist. They’re there. We have to engage with them, and the way art can do that can be quite powerful.

SW: Can we talk about bringing potentially controversial programming into spaces that see themselves as neutral?

LR: I’m working on a book right now on museums and cultural institutions and the myth of neutrality. It’s about how this myth prevails, even though it seems so obvious that a neutral place can’t exist.

This idea that a space can be neutral is just re-inscribing the values of the status quo, which results in a scenario where anyone taking up space, other than members of the dominant culture, whatever that may be defined as in any particular moment, is seen as aggressive or alternative or otherwise confrontational. Unless you see or reveal the presence of that so-called neutral position as something that’s quite specific, you might miss the biases embedded in those institutions, and in their decision-making. So what ends up happening is decision-making that just looks and sounds like [neutral] decision-making [but proves to be] actually ways of excluding certain people or art objects or aesthetics. That tension—it’s important to identify it, to talk about the fact that it exists. Then we can really understand how it implicates the entire institution and supports the status quo in a way that’s unacceptable to me at this point.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Inside, 1973 [courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, and the artist]

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Inside, 1973 [courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, and the artist]

SW: What we’re talking about is having these institutions, under capitalism, and how money is used to sway opinions or inform collections. But if all the grants go away, if we choose not to take funds from individuals and organizations, what’s the solution?

CK: To my mind, the solution is one of much more flexible budgeting processes so that the institution is able to respond more swiftly to demands coming from its primary constituency and, say, postpone an exhibition or collaborate with other institutions when funding fluctuates because of these demands or evolving funding expectations and standards. We must develop financial structures [wherein] we have more leeway, so we’re not stuck with a five-year budget and a five-year exhibition plan. This [approach] will require institutional partnerships and cultural alliances across different communities, cities, or states. Crucial for the success of such an approach is to clearly identify the core values for your institution—and supporting the ongoing, unending work of re-articulating these values all the time—because in the end, many sources of funding, many industries can be considered as compromised, and whether that’s acceptable or not depends on the cultural and political climate on the one hand, and the institution’s value on the other. This needs to be an ongoing discussion between board and staff.

LR: I also think that those discussions have to be open and transparent. The last chapter of my book will be devoted to imagining potential futures, because we can diagnose the problem all we like, but if we’re not actually trying to pursue different ways of working, what’s the point? It’s hard to do that within existing institutions because, to whatever extent, whether it’s the Queens Museum or the Whitney or the Met or The Laundromat Project or Recess, everyone feels precarious. Even though you look at the Met and think, “I can’t understand how they could possibly feel precarious.” They just ended their program at the Breuer building because they didn’t have the money to do it. Part of it is shifting the mind space somehow, to believe that we are actually institutions of great abundance, and that we materialize abundance in other ways. There is something paralyzing about that feeling of fighting over scarce resources.

CK: That’s where a feminist perspective is very useful: to acknowledge, to define the abundance. It’s not just dollars. It’s developing these networks and collaborations. So already you have co-ownership of significant works of art (for instance Bruce Nauman’s Days is jointly owned by MoMA and Schaulager in Basel). On a much smaller scale but not unrelated, that kind of shared programming, shared exhibition-making, staff and artist residencies across the country and beyond, I think that’s where we ought to go. It’s a lot of work but that is how we grow, how we can make a difference, and how we can think of “costs” and “resources” in a very different way.

LR: Our collaboration with Weeksville, for example, is really pertinent in this circumstance because there were intangible resources they brought to the program that were important and rich. Similarly, the Vera List Center provided some financial support that made it possible.

I agree with Carin, because what I’ve seen in our programming and in some of the work we did at the Queens Museum (particularly with the public library system), the programming that was really successful was because it was built on each other’s expertise and knowledge-bases and communities. The Queens Museum never pretended to be a frontline organization that could provide direct services, but we worked with many people who could provide direct services. We became a facilitator in that sense. It’s knowing what you do, knowing what you’re good at, knowing what your strengths are, and then really asking, are we different enough that we can give to one another?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art, 2016-2017, installation view [photo: Hai Zhang; courtesy of the Queens Museum]

SW: What have you learned from that process?

LR: I think it’s very interesting that in the US a lot of the very earliest cultural institutions were natural history organizations founded by nonexperts, naturalists, and “gentlemen farmers.” And there was this weird competition between New World Europeans and Old World Europeans, competing for who had the best flora and fauna.

SW: That’s a super weird competition.

LR: Yeah, it’s very odd, but it was there. What ended up happening was [that] it reified this strange nationalism around the museums holding the greatness of the nation. This condition spans various colonial histories, various continents, and other kinds of relations between peoples in vastly different geographies. The objects that were then committed to these institutions, that were studied by people, were given or provided by white male people of a certain level of wealth as objects for study. The value or the aesthetics or the importance of the material was then re-inscribed, because you had three, four, five, or six generations studying that same material. So that becomes what’s “excellent,” because that’s what we’ve been studying.

CK: In my master thesis, I compared American and European museums, and how the historical difference in funding structures has resulted in very different museum experiences. In Europe, art is by and large still a legacy of the pre-French Revolution aristocracy, and as visitor, you’re lucky to be let in. That’s why educational departments were never a priority at European Museums. Here, in the US, the assumption was that we had arrived in an “empty” country and [that] art served two purposes: nation building and education, [to] help museum visitors to develop specific skills that would be useful to “build” this country.

LR: But in the US, even if it’s largely rhetorical, there is a very specific desire for museums and cultural institutions to be places of the common good, to be locations of the commons, of education.

CK: Absolutely, and it makes for exhibitions that seek to be accessible. It also demythologizes art: it is learnable, teachable and its impact should be quantifiable. No wonder that the first art museums here always also had an art school. That’s not the case in Europe. In American museums, there is this belief that museums are places for everyone.

LR: Yes, that’s super American, even though I think a lot of the other ideas about what museums are and how they evolved, especially the grandiosity of museum architecture, like the Met or the Philadelphia Museum [of Art], came from European ideals, the Age of Enlightenment.

SW: Were we never neutral from the start?

LR: A friend of mine told me to read this Roland Barthes book, The Neutral. He envisions the neutral as this place that’s utopic. It can be anything. It’s so perfect it’s phantasmagorical. Neutral can be anything. It could be bad manners. It has the capacity to be anything, which I see as impossible. He describes a situation where he goes to the ink store to buy his Sennelier inks: he likes the hot pink and the bright yellow and the dark green and the blue and the whatever. He gets home and spills one of them and as he’s cleaning up this sort of muddy grey, he picks up the bottle, and realizes the color is called neutral. The neutral is actually something that’s marketable. You can market it, and it’s a thing—it’s a color, and this is what they made it look like. To me, with this example, Barthes undoes his whole point with this lovely moment about the inks because, in the end, the neutral is always something. It’s a question of who has defined that something.

CK: In diplomacy, so-called neutral countries play a certain useful function. Representatives of different nations come together in this supposedly neutral space because it can facilitate negotiating agreements, agreements that may not be possible in a space that is inscribed by one country’s particular agenda. Here, the concept of neutrality can be quite useful. Even if these agreements will later never be ratified in the home countries, they do stand as benchmarks. They have a presence, whether they are enacted or not. They do exist.

LR: Their existence helps map this other space.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, 1976 [courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, and the artist]

CK: Yeah, but for it to work everyone has to agree that neutrality exists.

LR: Could exist, yes.

CK: I’m also thinking of our next seminar, organized with the New York Peace Institute, a mediation service. In mediation, two opposing parties are brought together in the same space with no other prerequisite than that they have agreed to talk to each other. According to New York Peace Institute, conflict resolution in this case requires a private space, the promise of confidentiality, and gentle verbal coaching by the mediator. This is another type of free speech. And [another type] of a situation that rests on the idea or fiction of neutrality.

LR: Carin and I have known each other for a long time, and the thing that really has been super successful about the way we work together is that it’s all part of an ongoing conversation that sometimes spirals out into various tributaries and deltas. Sometimes those are not fruitful, but other times they are. We end up in places that we wouldn’t have otherwise. For both of us, the Assuming Boycott series and this one on freedom of speech have been about satisfying some learning that we want to do, expanding the ideas we have about a subject. That starting point has contributed to the ways the series has evolved, in some unusual ways or unexpected ways—certainly for me.

SW: Coming to a topic with questions and wanting to know more.

CK: Exactly, and being able to commit time and resources to such collaborative and joint learning—with the public. I think it’s rare to be able to step back and dedicate an entire year and a half to imagining and planning what this might look like. Trust is key, of course, and the curiosity to try and do this jointly, in exchange with many other “learners.” There are many rewarding aspects to this [process], but that’s the fun part. To recognize yourself or your questions in someone else and to have that person take you further and point you to areas where you wouldn’t have gone, it’s wonderful.

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS Fall 2019 “Strategies of Response.”

Sara Wintz is an arts and culture writer based in Providence, RI. Her recent interviews with Geeta Dayal, Beth Pickens, and Lavender Suarez are available online at The Creative Independent; she interviewed Mashinka Firunts Hakopian, Gilda Davidian, and Meldia Yesayan (“Valley Visionaries”) for the Fall 2018 issue of Art Papers.

Carin Kuoni is a curator, writer, and arts administrator whose work examines how contemporary artistic practices reflect and inform social, political, and cultural conditions. She is director/chief curator of the Vera List Center for Art and Politics at The New School, where she also teaches. She was director of exhibitions at Independent Curators International and director of Swiss Institute, and she has curated and co-curated numerous transdisciplinary exhibitions presented at institutions in the US and abroad. Kuoni is editor and co-editor of several anthologies, among them Joseph Beuys in America: Energy Plan for the Western Man; Words of Wisdom: A Curator’s Vade Mecum; Considering Forgiveness; Speculation, Now; Entry Points: The Vera List Center Field Guide On Art and Social Justice, No. 1; and Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production.

Laura Raicovich is a New York-based writer and curator. She is currently writing a book on museums, cultural institutions, and the myth of neutrality (Verso 2020). She was a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow at the Bellagio Center and received the inaugural Emily H. Tremaine Journalism Fellowship for Curators at Hyperallergic. She also co-curated Mel Chin: All Over the Place, a multiborough survey of the artist’s work, and served as the director of the Queens Museum. Before the museum, she launched Creative Time’s Global Initiatives, was Dia Art Foundation’s deputy director, and has held posts at the Guggenheim and Public Art Fund.