Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016, 2018, [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy of Artist and MoMA, New York City]

Share:

From psychedelic interpretations of Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland to a hypnotizing drag king roaming the streets of Manhattan, Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016 at The Museum of Modern Art [March 31, 2018–July 22, 2018] presented an ambitious overview of the artist’s transformative practice. As part of the first wave of conceptual artists, her work is largely driven by an idea, with the materiality of the art object providing a means to an end. Through a diverse selection of drawings, paintings, photographs, video, audio, and performance, the exhibition showed Piper in all her multiplicity.

Piper (b. 1948) has famously rejected the label of “black artist,” and for good reasons. Black artists often feel limited in their practices to create work focused solely on their experience as racialized “others.” As a light-skinned black woman who is often mistaken for white, Piper knowingly exploits her ambiguous racial appearance. This operation plays a key role in her work.

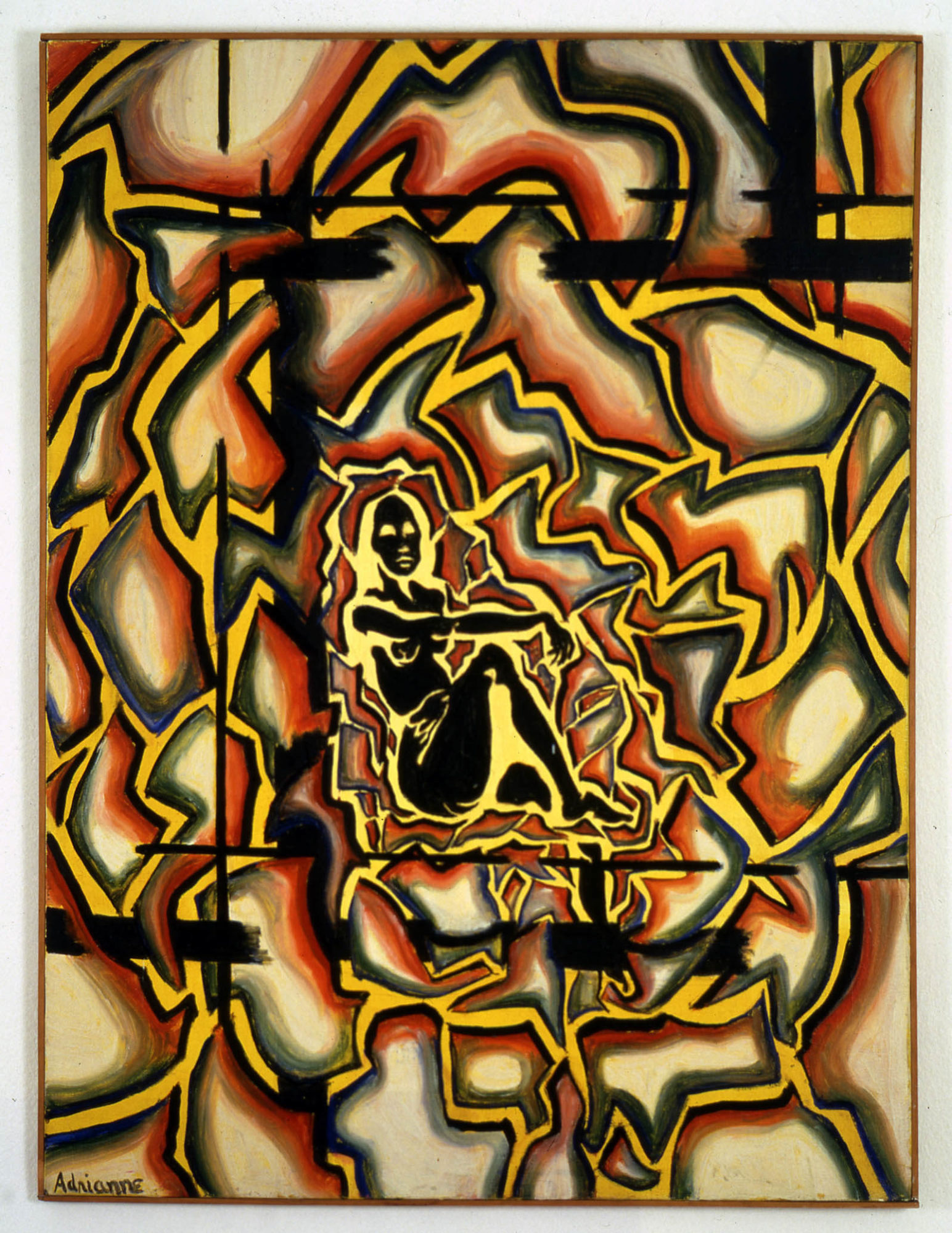

Much of Piper’s early work features a fevered exploration of consciousness. Her youthful experiences with psychedelic drugs influenced the most extreme examples. The show opened with a series of LSD-induced drawings and paintings from the 1960s, a time when the drug was still legal in the United States. The quotidian subjects of these works—which include Barbie dolls, self-portraits, and images from the novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—are rendered in a way that divorces them from reality. The vibrating acidic colors and warped compositions of her Alice in Wonderland illustrations recall scenes from Dante’s Divine Comedy rather than a children’s book, while her intricately drawn Barbie dolls, which appear to have been dissected and then crudely stitched back together, evoke Frankenstein’s monster. Her self-portraits, such as LSD Self-Portrait from the Inside Out (1966), convey a sense of depersonalization, physically resembling Piper but distorted through jagged, variegated shapes, placing them in the same version of unreality as Alice and the monstrous dolls. A New York City native, Piper began attending the School of Visual Arts in 1966, where her practice dramatically shifted away from figurative art toward an experimentation with the subconscious that continued throughout her later work.

Adrian Piper, LSD Self-Portrait from the Inside Out, 1966, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 inches [photo: Boris Kirpotin; courtesy of the artist, Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation, Berlin and MoMA, New York City]

Simultaneously, minimalist artists such as Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, and Sol LeWitt were reacting against the perceived dramatics of the abstract expressionists. Their reductive principles are immediately evident in her work of the time, from visually striking sculptures such as Recessed Square (1967) or the imposing Protruded Rectangle Canvas (1967) to her series Drawings about Paper and Writings about Words. Focusing on basic design elements such as line, shadow, and shape, the latter series features an array of delicate compositions executed with pale hues of pencils, crayons, and pastels on notebook paper. Understated and frank in its simplicity, the series invites us to value the materials themselves over the images that they create, a distinction that is essential to Piper’s practice as a conceptual artist.

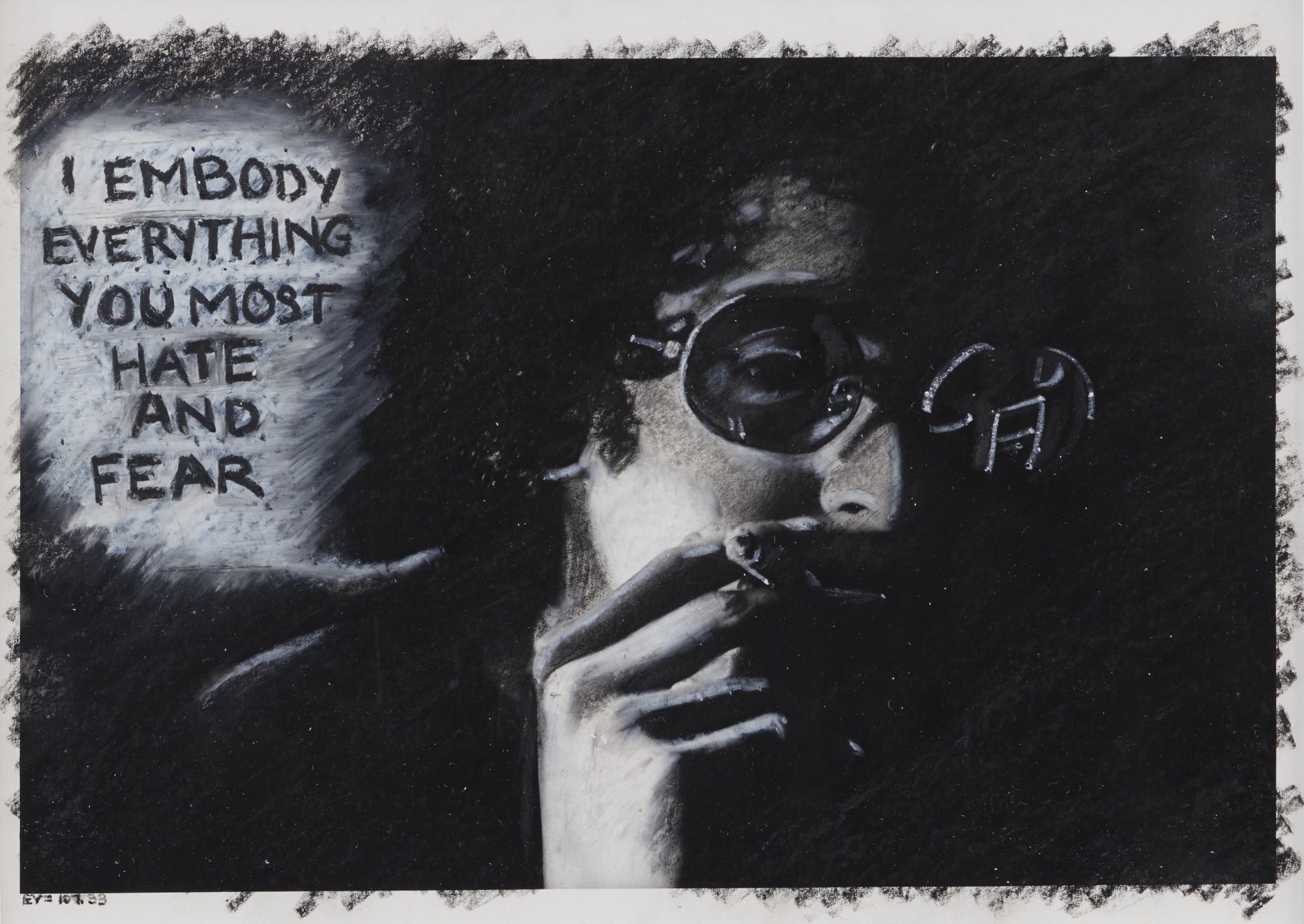

The creation of the Mythic Being persona in 1973 marked an exciting shift in the artist’s work. The character typically dons a black T-shirt or poncho, tattered jeans, mirrored sunglasses, a bushy afro, and thick mustache. A macho alter-ego, the Mythic Being is a perfect amalgamation of the subconscious biases and performative identities the artist explores in her work.

Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being: I Embody Everything You Most Hate and Fear, 1975, oil crayon on gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 inches [courtesy of the artist, Collection Thomas Erben, New York City, Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation, Berlin and MoMA, New York City]

The Being is ubiquitous in the work that follows. One moment he appears via sepia-toned thumbnails in the Village Voice—next to ads for discounted Vogue posters, pornographic tapestries, and naive art—and the next, we see him listlessly wandering around downtown New York and Harvard Yard in Cambridge. In one video, the comically diminutive Being can be seen roaming a crowded street and repeating a seemingly arbitrary mantra: “No matter how much I ask my mother to stop buying crackers, cookies, and things, she does anyway and says they’re for her, even if I always eat them. So, I’ve decided to fast.” The bizarreness of the scene is pushed further by the reactions of passersby, which range from outright laughter to total confusion. Later, the Being is transformed into a comics character in a series of hand-colored photographs. His speech bubbles read, “I EMBODY EVERYTHING YOU MOST HATE AND FEAR” and “SAY IT LIKE YOU MEAN IT, BABY CAKES,” among other assertive expressions. Pompousness aside, the witty catch phrases endow the would-be hero with an undeniable, charismatic cool.

The deeply layered comedy of the Mythic Being is heightened by its subversive take on the constructed aspects of identity, and how others’ perceptions can affect the ways in which it is expressed. The character shows the ways that identity is fluid and multifaceted, but also how it is constructed both internally and externally. Piper’s later series, including Close to Home (1987) and Vanilla Nightmares (1986–1989), directly address such biases by exploring the fears and fetishes placed on racialized or marked bodies.

Ultimately, Ms. Piper’s work centers on reclaiming identity as the most crucial form of self-awareness and actualization. The show at MoMA, in all its complexity and nuance, offered a complicated view of the artist and her intersectional approach to understanding the boundaries of identity. For Piper, the performance of identity is just as significant as identity itself.