Access+Ability

Access+Ability, installation view [photo: Chris J. Gauthier © Smithsonian Institution, courtesy of the artist, Cooper Hewitt, and Smithsonian Design Museum, New York]

Share:

What would a completely accessible museum look like? Removing all barriers for every visitor to a cultural institution is an impossible aspiration, but also a challenging and exciting proposition for exhibition design. At this time, perhaps no museum comes closer than the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. Expanding far beyond the legally required accommodations offered at all major museums—such as ramps and pathways wide enough for wheelchairs, and signage labeling bathrooms and elevators with raised characters and braille—Cooper Hewitt offers as part of its standard practice services that are still being hesitantly piloted elsewhere. The museum has been providing relevant objects for tactile exploration, and optional “dynamic descriptions,” which recount sensory and verbal qualities alongside curatorial scripts, available for any docent-led exhibition tour.

In short, Cooper Hewitt’s team understands that accessibility work is a fundamentally creative process, rather than an issue of mere compliance—the latter being the attitude of many major American art and design museums. In the major exhibition Access+Ability, Cooper Hewitt’s commitment to creating broadly defined access intersects with and amplifies the show’s thematic explorations of products that fall under the category of inclusive design. The result is a powerful experience in which the museum’s policies and infrastructure perform the curatorial point of view.

McCauley Wanner and Ryan Palibroda Prosthetic Leg Covers, 2011, digitally fabricated ABS plastic, polyurethane straps, metal hooks, manufactured by McCauley Wanner and Ryan Palibroda for Alleles Design Studio [photo courtesy of the artists, The ALLELES Design Studio Ltd., Cooper Hewitt, and Smithsonian Design Museum, New York]

The exhibition is divided into three broad sections, each devoted to a purpose or process that the various designs support: mobility, connecting, and daily routines, as classified by co-curators Cara McCarty and Rochelle Steiner. Many objects are assistive devices for particular, practical uses, updated to take advantage of new technologies, such as the SmartCane (IIT Delhi, 2014), which can detect obstructions up to three meters away by using ultrasonic waves that trigger vibrations in the cane’s handle. Many fall into the category of wearable tech, such as headsets and watches. And the exhibition focuses in particular on how these designs, whether for accessories or prostheses, are beginning to be treated with attention to style as well as function; a series of prosthetic leg covers by ALLELES Design Studio, in particular, shows how simply providing aesthetic options to people missing limbs is a case of user-centered design that considers different abilities not as a problem to solve but as an experience of real people in their everyday lives. This approach implements the concept of the user/expert, defined in 1997 by Elaine Ostroff, one of the creators of the Principles of Universal Design, as “anyone who has developed natural experience in dealing with the challenges of our built environment.” Their examples of user/experts include “parents managing with toddlers, older people with changing vision or stamina, people of short stature, limited grasp or who use wheelchairs.” Imagining end users as the experts means, to echo the activist phrase “nothing for us without us”: designs are not made without their input and expertise.

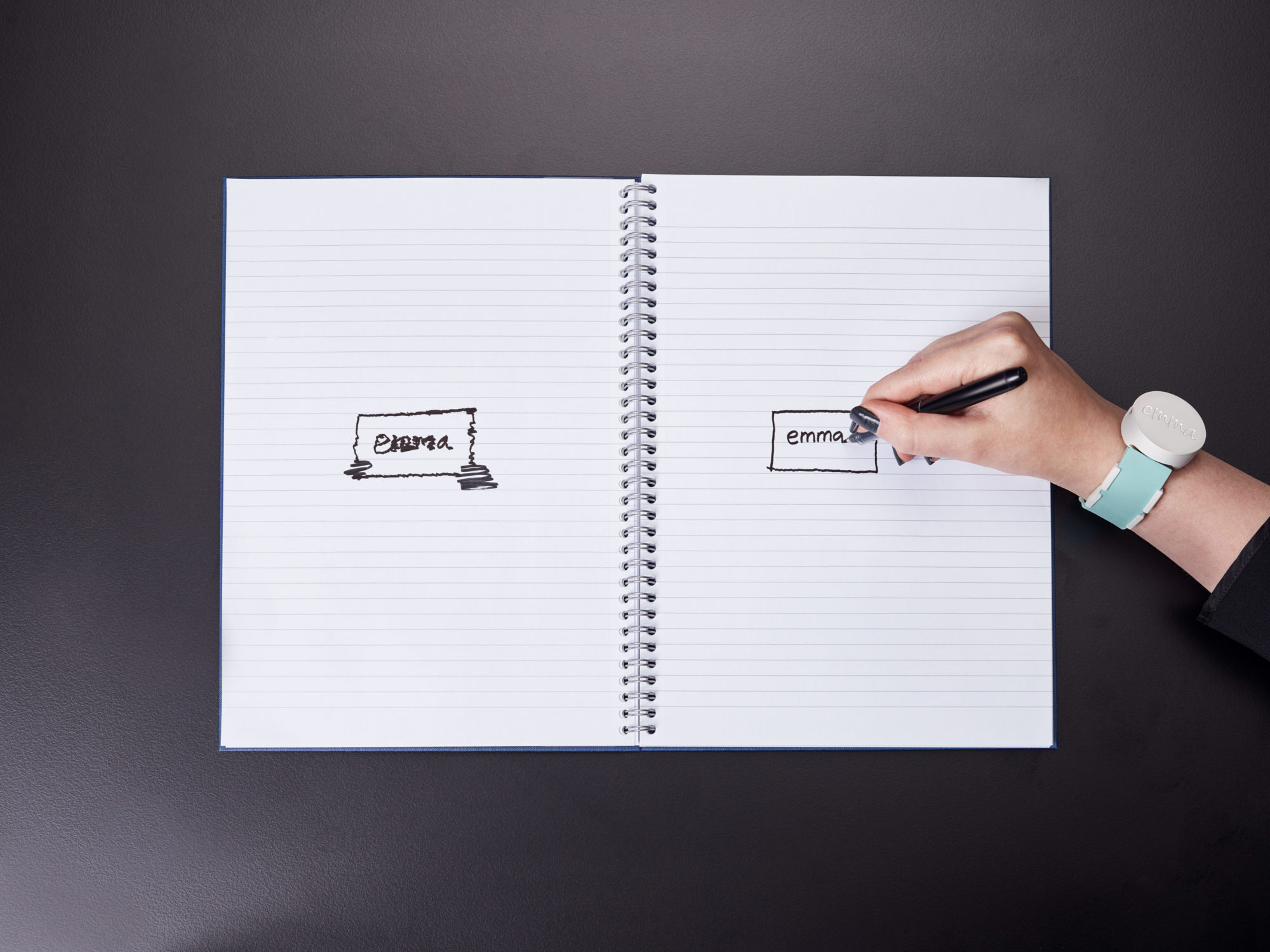

Haiyan Zhang and Nicolas Villar, Emma Watch (Prototype), 2016, 3D-printing, Custom PCB, manufactured by Microsoft Research [photo: © Alex Griffiths; courtesy of the artist, Microsoft Research, Cooper Hewitt and Smithsonian Design Museum, New York]

The most exciting set of design objects on display in Access+Ability apply emerging tools related to responsive haptic vibration. Beyond being used for basic signaling, as with the SmartCane, several of these objects apply cutting-edge (and well-funded) technologies for the next generation of virtual reality platforms, such as VR vests and suits. In this exhibition, these systems are used for biofeedback, as with the Emma Watch prototype (Nicolas Villar, 2016), a 3-D printed watch that can monitor the hand tremors of people with Parkinson’s; and the Path Feel insole (Walk With Path Limited, 2014), which provides vibrational feedback to people at risk for falls by amplifying the touch sensation when feet touch the ground, helping users to better identify accurately when their feet have made contact.

The exhibition also highlights haptics as a way of translating between senses. One intriguing object in the show, the SoundShirt (designed by Ryan Genz for CuteCircuit, 2015–2016), transforms an aesthetic experience from hearing into touch, rendering orchestral music as a tactile experience by using sensors on different areas of a shirt that correspond to distinct parts of the orchestra. Similarly, a vision aid (Brainport Vision Pro by Wicab, 2017) uses a camera headset to turn information about shapes in the physical world into vibrations that can be felt—and, after a period of learning, seen—through a device placed on the user’s tongue. This class of objects is evidence that inclusive design is one of the most richly inventive fields for body-centered communication technologies.

Elizabeth Dopey and Stephen Gilson, Afari mobility aid, 2010-14, aluminum, BMX bike wheels, bike components, manufactured by Mobility Technologies [photo courtesy of the artist, Mobility Technologies, Cooper Hewitt, and Smithsonian Design Museum, New York]

The objects in the show were chosen collectively by the co-curators along with disability activists, caregivers, medical professionals, and, crucially, end user/experts—answering the consistent chorus from the disability community to be included on decisions from day one. One effect of this broad collaboration is that equal curatorial attention is given to quotidian items as flashy new tech. A spoon and the PillPack designed by IDEO and Tyler Wortman (its success demonstrated by Amazon’s recent billion-dollar purchase of the brand this past June, after the exhibition opened) sit side by side with voting machines and racing wheelchairs. The breadth of these items show the scale of solutions that matter to those navigating environments not designed for them. The exclusionary structures that keep people with disabilities out of decision-making are sadly as common for museums as for any other institution. Access+Ability is an example of the curatorial richness that occurs when there is true diversity involved in decisions around representing these users.

Being physically present at an exhibition in the first place is an issue of accessibility, whether related to mobility, time, or money. Admirably, the exhibition also accounts for audiences who won’t be able to visit in person at all. I first visited Access+Ability when it opened in December 2018. My plane tickets from California cost several hundred dollars and some carefully-hoarded vacation time. At the time, New York was bitterly cold, and I struggled on my walk from the subway, finding it occasionally difficult to walk against the wind in Cooper Hewitt’s Upper East Side neighborhood.

During this first visit, I used a pen offered to visitors to touch the labels for items I wanted to bookmark and return to later. Months afterward, I logged in at the Cooper Hewitt website by using a code from my entry ticket to retrieve my online archive of items. They were tagged in the order I had visited them, as beautifully and rigorously catalogued as any museum collection’s website. Visitors to the site can also browse the complete checklist of objects, which is optimized for web accessibility (with alternative text for visual images, well-structured pages, and clear navigation). To be virtually present at a show while one’s body is physically elsewhere: this is the ultimate inclusive exhibition design move, and another example of going so far beyond mere compliance that providing accessibility accommodations becomes a kind of social form. That isn’t to say technology and internet access create pure and simple democratic entry to culture. Many barriers will still be in place for those whose presence at cultural institutions is erased in various ways. However, the effort that the Cooper Hewitt makes, and the labor it has invested, to catalogue, clear rights, and all the other activities required to put an entire exhibition online is deeply admirable. It’s the kind of work that is all too often invisible to people who have the privilege of not needing it.

This review originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.