Sitting Beside Yvonne Rainer’s Convalescent Dance

niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa, still from Black Power Naps, 2019 [photo: Xeno Rafaél, image courtesy of the artists]

Share:

On February 2, 1967, Yvonne Rainer performed a version of her signature dance, Trio A at The Playhouse at Hunter College.1 Rather than as a trio, Rainer performed alone, and called this particular iteration Convalescent Dance. It was so named because Rainer performed the dance in a “convalescent—that is, weakened—condition” after her “slow recovery from a serious illness,” which included abdominal surgery in October 1966, and rehospitalization in the weeks just preceding the performance. The dance, which runs in time according to the pace of each individual performer and averages at five minutes, was, according to Rainer’s memory, “slower.” She also recalls being “wobbly on her legs.”2 The last of the variations that distinguish Convalescent Dance from the original or any other iteration of Trio A is that Rainer performed in monochrome; her white shirt, white pants, and white shoes, evoked associations of neutrality, clinicality, and pacificity.

Convalescent Dance took place during Angry Arts Week, an artist-led Vietnam War protest that occupied New York City’s public spaces from January 29 through February 5, 1967. More than 500 artists participated, with an estimated 62,000 attendees.3 Angry Arts Week coincided with the release of the January 1967 issue of Ramparts, a political magazine that was an early opponent to the War. In this issue, Human Rights lawyer William F. Pepper published an article entitled “The Children of Vietnam” in which he described the visits he made to Vietnamese orphanages, hospitals and shelters as a freelance correspondent in the spring of 1966. Accompanied by equally distressing photographs taken by Pepper, the article is graphic in its description of the wounds, primarily the result of napalm fire and white phosphorus, obtained by Vietnamese children and the conditions by which they went untreated. Images of victims of napalm raids were repeatedly used to incite an emotional response and provoke action during Angry Arts Week. For example, sharing the same stage with Rainer the night of her performance, Margot Colbert presented Vietnam, which featured “a model bombing airplane, a number of dispirited ladies wandering around dispiritedly and an unseen but far from unheard gentleman reading out portentously muddled news headlines.”4

Amid a spectacle intended to function as provocation and call to action, Yvonne Rainer stood in front of an audience for roughly five minutes, slowly and deliberately performing the movements of a dance designed to be a statement against spectacle while her body was in a debilitated state. Dismissing questions of what pain looks like, a search for symptoms in which diagnosis and representation are parallel endeavors, the work favors a question of what pain does, of how we reconcile this action—not through the performance of pain, but performing in physical pain—in the context of protest, especially one in which images of wounded bodies were paraded as a testament to atrocity. Rainer later directly articulated Trio A’s emphasis on corporeal presence in response to the televising of the Vietnam War in a statement that accompanied a performance in April 1968: “It is a reflection of a state of mind that reacts with horror and disbelief upon seeing a Vietnamese shot dead on TV—not at the sight of death, however, but at the fact that the TV can be shut off afterwards as after a bad Western. My body remains the enduring reality.”5 Under its modified conditions, Convalescent Dance transformed Trio A into a statement of protest. But rather than the active instantiation of opposition, Rainer’s protest takes the form a negative action, the withdrawal from engagement that characterizes boycott and refusal.

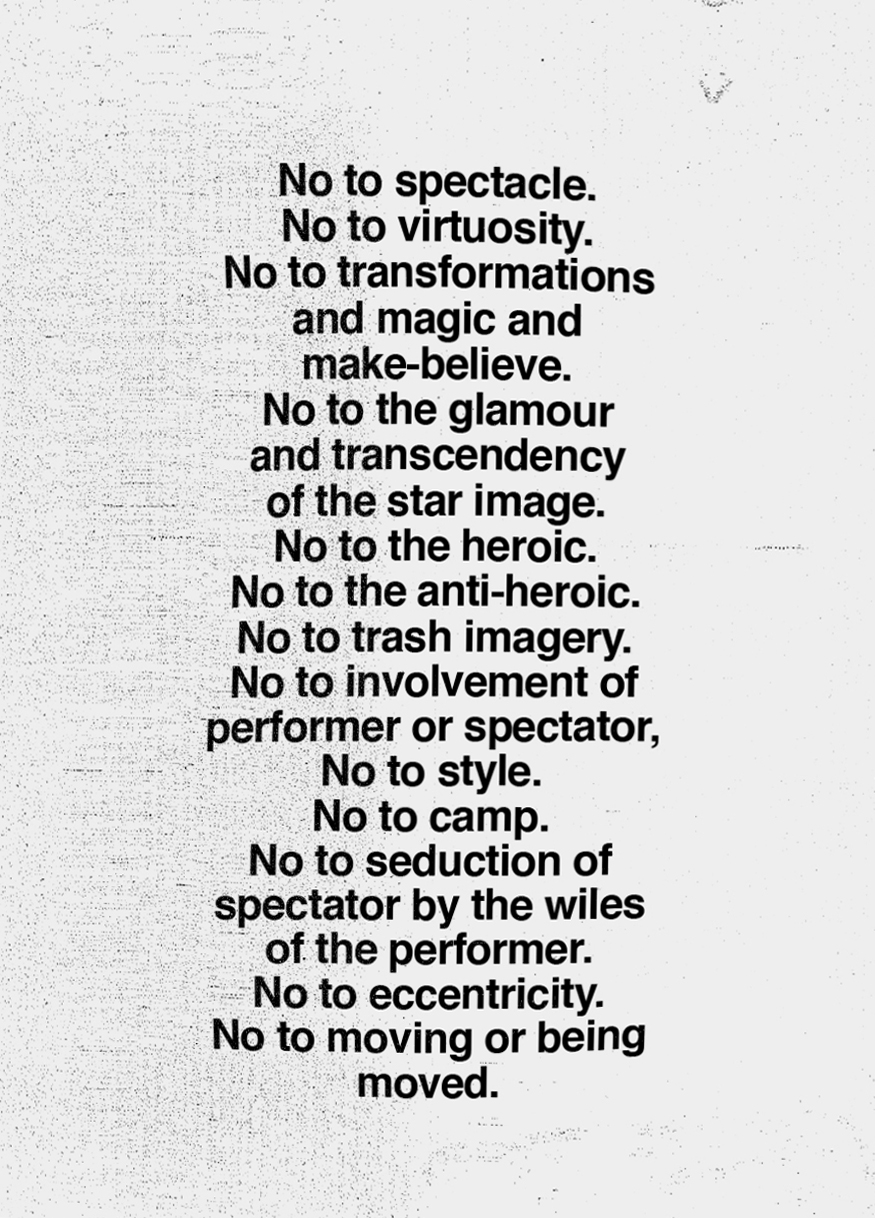

In many ways, Rainer’s Trio A is already a refusal to engage with many of the predominant tents of classical and modern dance. With dozens of variations introduced to its format since Rainer first performed it in 1966, Trio A can be understood as a test of the limits of dance under different conditions. Convalescent Dance introduced four variables to the Trio A format: a single performer; a white costume; a convalescent state, a stage of protest. Trio A, and by extension Convalescent Dance, includes no grand gestures, no epic feats, no gravity-defying demonstrations of skill or agility. As such, it can be considered the dance equivalent of Rainer’s “No Manifesto,” published in the same 1968 statement. Simplified variations of ballet movements scaled to a non-athletic pace and intensity associated with everyday activities, such that the movements incorporated into Trio A elevate parts of a daily routine elevated to the level of dance. “What is seen is a control that seems geared to the actual time it takes the actual weight of the body to go through prescribed movements.”6

Rainer choreographed Trio A so that it could be performed by most people, requiring no dance training, only persistence and practice. Despite the dance’s relative brevity and appearance of ease, Trio A is deceptively difficult for a novice to perform. Even trained dancers can find it difficult, as skills need to be unlearned to properly perform it.7 The dance would be even more difficult to perform in a convalescent state. Rainer troubles conventional notions of mastery to instead emphasize routine, writing of the dance, “It is my overall concern to reveal people as they are engaged in various kinds of activities—alone, with each other, with objects—and to weight the quality of the human body towards objects and away from the super-stylization of the dancer.”8 The dance’s choreography remains engaged in daily routine even as Rainer’s illness affected her ability to perform. Pain and illness ebb and flow throughout Trio A’s history as Rainer healed and relapsed. Some of the more recent performances of the dance, such as Trio A: Geriatric with Talking, 2010, incorporate the physical fact of her aging body as she “talked about … age-related inadequacies while performing the dance at the age of 76.” She remarked in an email exchange, “Getting up and down off the floor requires a lot more maneuvering than it used to.”9

Yvonne Rainer, No Manifesto, 1965.

Stairs, the fourth part of The Mind is a Muscle sequence, is also a response to Rainer’s illness and recuperation, and involved the dancers “learning” Rainer’s “watery-legged movement as [she] shakily negotiated running, crawling, getting from a chair to a high stool and back down again.”10 Where Stairs operates in the realm of physical mastery by affecting the body to appear physically weakened, in Convalescent Dance weakness vis-à-vis illness is integrated into the dance as the performing body’s state or condition.

No narrative arc pushes any one movement towards the next or towards finale. Each movement proceeds after another as a sequence of tasks on a to do list, performed in a seamless continuum. No expression of emotion or inflection of gesture elevates one movement above the next in a bodily articulation of Rainer’s statement: “no one thing is any more important than any other.”11 No movement repeats, exacerbating Rainer’s acknowledgment that “dance is hard to see,” and, as Carrie Lambert-Beatty argues in her monograph on Rainer, making this particular dance especially hard to photograph.12 Rainer writes in her “A Quasi Survey on Some ‘Minimalist’ Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimalist Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, Or, An Analysis of Trio A”: the dance “dealt with the ‘seeing’ difficulty by dint of its continual and unremitting revelation of gestural detail that did not repeat itself, thereby focusing on the fact that the material could not be easily encompassed.”13 Trio A is performed by three dancers, simultaneously but not in unison, making it even more resistant to tracking and holistic comprehension by an audience. Furthermore, as Lambert-Beatty notes, “Very often some body part—a foot, a shoulder—must begin a new movement before the rest of the body has finished the first. This internal staging ensures that no composed bodily picture is every produced.”14 Through this modification in phrasing, Rainer creates a dance that resists visibility and comprehensibility. Set against the backdrop of a protest against a televised war, one that itself activated images of the disabled, not as people but as wounds, Rainer refused to create a trackable image.

Trio A’s presentation of the body as a physical material—its object-likeness rather than its containment of subjecthood, “the fact of display,” the “one thing after another” effect of modified phrasing, and the quality of the dance’s movements as “task-like” are some of many points of correspondence Rainer identified between her choreographic practice to the work of Minimalist artists involved to with Judson Dance Theatre.15 Like the Minimalists, Rainer prioritized the “physical fact of the body” above the relay of emotion, individuality, and personhood. Rainer writes, “That action can best be focused on through the submerging of the personality; so ideally one is not even one’s self, one is a neutral doer.”16 The materiality of the body is emphasized in its “unenhanced physicality” and correlated to the workings of “cogs and gears, cams and levers.” However, by qualifying movement as “task-like,” Rainer conjures associations to the assembly line worker more than the assembly line itself. Such associations would resonate at a higher register in a context in which burning flesh was evoked.

***

Convalescent Dance has been a touchstone, an interlocutor, and a companion to me in a period of personal illness and concurrent national protest. Panic was my immediate response when, in the winter of 2013, I began waking from night terrors to find the right side of my body clenched in a state of partial paralysis. Over the years in which the most severe symptom of what would be diagnosed by practitioners of Western medicine as hypochondria and by Chinese medicine as complications from the removal of my gallbladder, persisted, Yvonne Rainer’s Convalescent Dance served as an applied philosophy for disentangling the emotional response of my mind to my symptoms and from the “physical fact” of my body. I learned that more aggressive actions of forcing movement only increased my muscles’ resistance. Instead, embodying the role of “neutral doer” allows me enough muscular release to regain motion. I enact this cognitive and physical shift daily, though the cords, like the invisible strings of a marionette, that animate living flesh remain ceaselessly taut and aflame in a line that runs from the back of my eye, over my head, across my shoulder, around my liver, and down to my hip, along the path of the gallbladder meridian. The task-likeness of my movements are more akin to slackening and the negative action of withdrawal.

The fact of my chronic pain, already invisible, is something that I show only to those with capacity to comprehend it, though I negotiate this tension I hold with autobiography by meditating on Convalescent Dance, and other works from this period of Rainer’s engagement with Judson Dance Theatre in which she incorporates an autobiography of illness and, literally, puts her ailing body on stage.17 I disclose here only partially, listing only one of my symptoms, and do so begrudgingly. This personal antagonism I feel toward disclosure stems, in part, from not wanting to be the subject of my own work. Disclosure is a trope of disability writing that asks us, the chronically ill and disabled, to repeatedly testify and give evidence for illness to maintain its validity. It puts one’s symptoms on a stage for a viewer to judge their severity or realness. This stage, already a precarious space for those of us who have been conditioned by internalized ableism––by not having the fact of our pain believed, amplifies doubt. The process of disclosure mirrors countless narrations I have given to countless doctors, and then to the therapists to whom they referred me when I wasn’t taken seriously, and to the psychics, astrologers, priests, and other spiritual healers I sought out after a fact of my body went unacknowledged for five years.

A course of treatment, both personal and medical, is hinged to every act of narration. In the moments when I was most sick I chose withdrawal from those who lacked an apparatus for understanding, and could not “feel” my pain, rather than expend my dwindling energy reserves in tedium of explanation. Such a dilemma is present in the reception of Convalescent Dance. New York Times dance critic Clive Barnes described it as “a dance of tap and gesture yet with a sense of style and feeling so that Miss Rainer, in white pants and sweater, made the whole world seem wistfully delightful.”18 As Erica Levin writes, “his review registers none of the vulnerability or frailty of a body performing while still in the throes of recovery. Lambert-Beatty argues that the work approaches the limit of what one can know of another body by way of kinesthetic empathy, a conclusion that Barnes’s review only further confirms.”19 In this way, Convalescent Dance places the invisibility of illness against its spectacle.

I am not trying to make a case for empathy or compassion. Both are the imaginative practices that are not synonymous for real care. Rainer implied as much in “No Manifesto:” “No to moving and being moved.” Rather than the “gulf” described by Levin, my decision to withdraw from an uncomphrending public opened the door to the intimacies of community. My antagonism with personal disclosure is also a resistance to individualization. For me, disability is less an identity than it is a method and a politic. Disability is a communal space in which I connect with people whom I rarely have the opportunity to share physical space with. As my friend Riva Lehrer has so eloquently written, “Disability can act as a radical alchemist’s laboratory of relationship possibility. A place where love might be invented beyond the roles of gender, and leave behind inherited, failed mimicries of intimacy.”20 I see this radical reimaging in Carolyn Lazard’s In Sickness and Study (2015), a series of self-portraits in which Lazard pictures the length of her arm from the insertion point of an IV tube to a hand that holds the book she is reading while receiving iron infusions. When posted on Instagram, the tube attached to Lazard’s body is reconfigured as a virtual lifeline to a community that supports and sustains her through this treatment. Crip intimacy is unbound by the restrictions of time and place. This is why I’ve never needed to speak to Rainer about my long-term and ongoing meditation on a dance she made more than 50 year ago.

By performing in a convalescent state, Rainer stressed the urgency of protesting by mustering her limited strength during a period of recovery. For the many people who exist in continuous or chronic states of debility, overriding is not an option. In Sick Woman Theory, Johanna Hedva describes listening to the sounds of Black Lives Matter protesters gathering and chanting while she was bedridden in her apartment in Los Angeles. Hedva expands an idea of disability to those who are debilitated by structural systems and asserts that many disabled and debilitated people are unable to meet Hannah Arendt’s definition of the political as participants in actions that happen in public. She writes: “it seemed to me that many for whom Black Lives Matter is especially in service, might not be able to be present for the marches because they were imprisoned by a job, the threat of being fired from their job if they marched, or literal incarceration, and of course the threat of violence and police brutality–but also because of illness or disability, or because they were caring for someone with an illness or disability.” To Arendt, she asks, “How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?”21

For others, whose survival is dependent upon working, overriding one’s body is the only option, with rest and convalescence being inaccessible states. Recognizing that “the distribution of rest is determined by race, with people of color regularly getting less sleep than white people,” niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa staged daily Black Power Naps at Performance Space New York, in January 2019 as part of curator Jenny Schlenzka’s No series. In a conscious nod to Rainer, Schlenzka updated the artist’s “No Manifesto” for the present moment. Notably, the statement of negation now contains three affirmative statements that underscore a politic of interdependency. “Being together,” “caring for each other,” and “making something out of nothing” are integral to overcoming the disproportionate assignment of rest that is “continued form of state-sanctioned punishment born from the ongoing legacy of slavery” for Sosa and Acosta.22Black, migrant and indigenous communities, and queer and trans people are invited to rest and leisure within an installation of colorful and comfortable pillows and blankets that includes readings and devices intended to increase the quality of sleep. Sosa and Acosta’s project also asks their host institutions to make strategic interventions to be more inclusive of these communities which are often not considered as a primary audience. In doing so the artists aim to make a structural change. For Acosta, “We need to be asking for economic reparations, but we also need to be asking for energetic reparations, and that means abolishing structures that benefit off of our lack of sleep. We’re looking at an economy, a moment, where Black folks, indigenous folks, brown folks, migrant folks, are dealing with a sleeplessness, a restlessness that is connected to productivity, capitalism, a production-based society.” Sosa expands: “When we talk about rest in terms of reparations, we’re not only talking about sleeping per se, we’re also talking about downtime; leisure time that you don’t spend sleeping, that you are able to spend cultivating yourself, imagining yourself, just existing; to basically rest up, to stop having a function in society for a bit.”23

Convalescing is reconfigured as a radical act.

niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa, still from Black Power Naps, 2019 [photo: Xeno Rafaél, image courtesy of the artists]

niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa, still from Black Power Naps, 2019 [photo: Xeno Rafaél, image courtesy of the artists]

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.

References

| ↑1 | I had originally imagined this essay would to bring together Rainer’s Hand Movie, 1966, with the hand dances Kazuo Ohno performed when he was no longer able to walk. I also intended it to be a companion piece to “Mobility and Mobilization,” published in What Now?: On Future Identities (London: Black Dog Press, 2016. This essay has taken a different turn but I wanted to acknowledge the original idea. I began writing this essay in 2013 when I first experiencing the symptoms described here. This experience and my thinking about Convalescent Dance and Intravenous Lecture inspired my exhibition, Care, a rehearsal for a performance at Roots & Culture in Chicago in August 2016, and expanded as Care, A Performance at Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City in July 2017 and Sala Diaz in San Antonio in October 2017. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Email correspondence with the artist, April 1, 2013. Carrie Lambert-Beatty footnotes the following: Rainer suffered a severe intestinal blockage caused by adhesions from a childhood appendectomy and had emergency surgery in October 1966, immediately after the first of the “Nine Evenings” events at the New York Armory organize by the Experiments in Art and Technology initiative. The intestinal problem recurred in early 1967, within two to three weeks before Rainer performed Trio A as Convalescent Dance. |

| ↑3 | Francis Frascina, Art, Politics, Dissent, (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2000), 125. |

| ↑4 | Clive Barnes, “Dance: Angry Arts at Hunter College,” The New York Times, February 3, 1967. |

| ↑5 | Yvonne Rainer, “The Mind is a Muscle,” program accompanying the performance of The Mind is a Muscle on April 11, 14, 15, 1968 at The Anderson Theatre. The document notes that the statement was written in March 1968. Available online at: /https://www.amherst.edu/media/view/228735/original/the+Mind+is+a+Muscle.pdf |

| ↑6 | Emphasis in quote is Rainer’s. Rainer, “A Quasi Survey” in Work, 61-73. |

| ↑7 | Julia Bryan Wilson describes the process of learning Trio A as a untrained dancer in “Practicing Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A,” October 140, Spring 2012, pp. 54–74. |

| ↑8 | Catherine Wood, Yvonne Rainer: The Mind is a Muscle (London: Afterall Books, 2007). |

| ↑9 | Email with the author, April 1, 2013 |

| ↑10 | Yvonne Rainer, A Woman Who—: Essays, Interviews, Scripts (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999) p. 44. |

| ↑11 | Rainer, “A Quasi Survey,” in Work, 67. |

| ↑12 | Lambert-Beatty, Being Watched, 1. |

| ↑13 | Rainer, “A Quasi Survey” in Work, 61-73. |

| ↑14 | Lambert-Beatty, Being Watched, 134. |

| ↑15 | A Rainer, “A Quasi Survey” in Work, 61-73. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | In “Miscellaneous Notes” of Rainer’s Work, she writes, “Objects in themselves have a “load” of associations (e.g. the mattress—sleep, dreams, sickness, unconsciousness, sex) but which can be exploited strictly as neutral “objects.” Mat, the third part of The Mind is a Muscle set, “was preceded by a tape of [Rainer’s] voice reading a letter from a Denver doctor to a New York surgeon describing in technical medical terms the details of the gastrointestinal illness with which [she] was hospitalized at the time of this performance.” She writes, “It was one of many attempts to deal—via my profession—with the natural catastrophe that had befallen my body. I was using autobiography as ‘found object’ without any stylistic transformation.” Hand Movie (1966), a choreographic study in which Rainer documents the flexibility of her fingers and hand, was made while Rainer was hospitalized for the same illness. Her 1996 film MURDER and murder, Rainer addresses her breast cancer and mastectomy; menopause in the subject of Privilege, 1990. |

| ↑18 | Barnes, “Dance: Angry Arts at Hunter College. |

| ↑19 | Erica Levin discusses Convalescent Dance as a counterpoint to Carolee Schneemann’s Snows, also featured during Angry Arts Week. Erica Levin, “Dissent and the Aesthetics of Control: On Carolee Schneemann’s Snows,” World Picture Journal, (Summer 2013). |

| ↑20 | Riva Lehrer, “Golem Girl Gets Lucky,” Sex and Disability, eds. Robert McRuer and Anna Mollow (Durham: Duke UP, 2012), p. 244-245. |

| ↑21 | Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory,” Mask, January 16, 2016, http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory. |

| ↑22 | Performance Space New York, “No Series,” https://performancespacenewyork.org/shows/black-power-naps |

| ↑23 | Fannie Sosa cited by Sarah Burke, “These Artists Want Black People to Sleep.” Broadly, VICE, January 7, 2019, www.broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/neppam/black-power-naps-fannie-sosa-niv-acosta. |