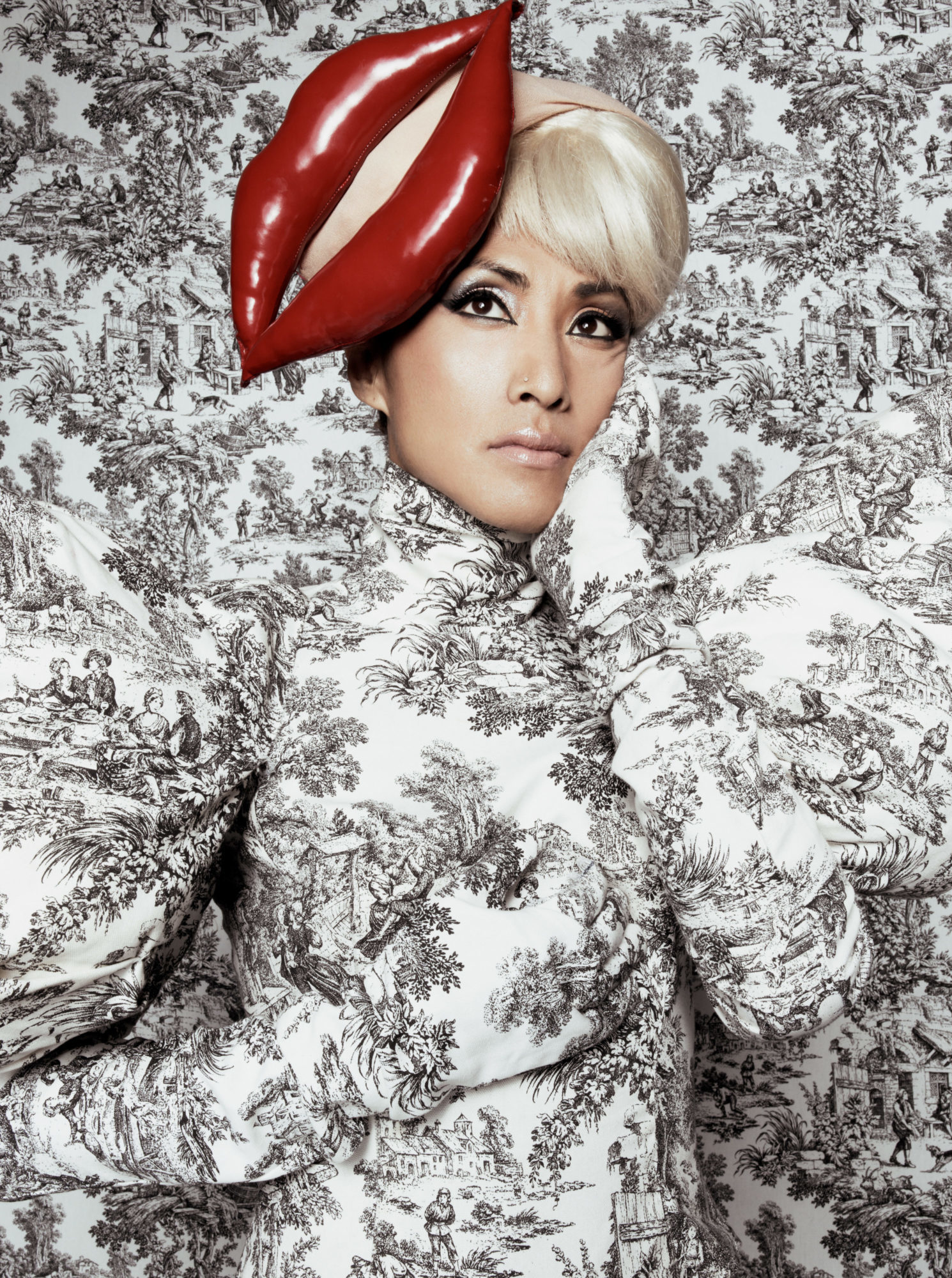

Yozmit: Embodiment And Metamorphosis

Photo: HongJangHyun

Share:

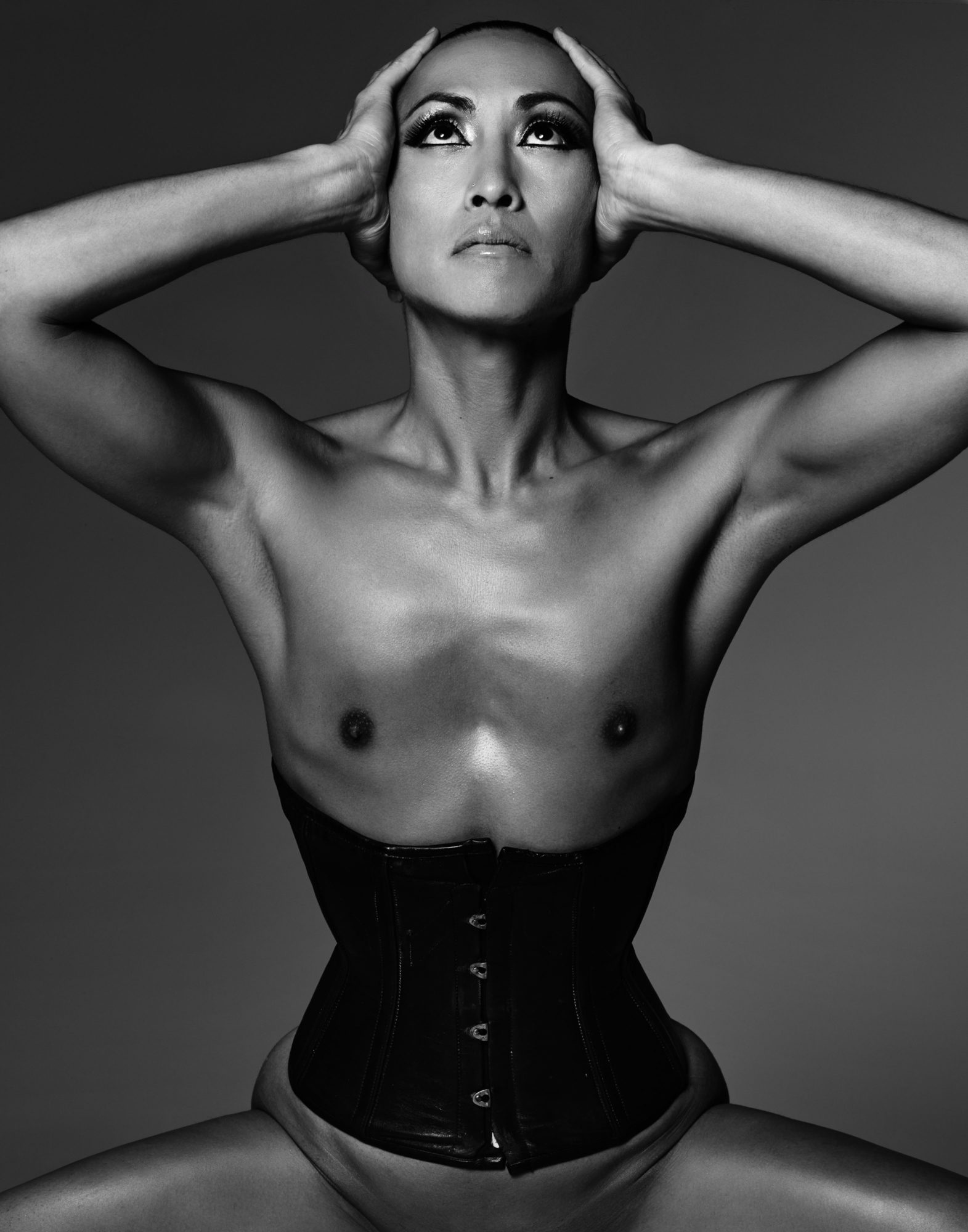

Los Angeles–based performance artist, costume designer, and singer-songwriter Yozmit emphasizes the body as a site of transformation. Her ornate costumes elicit a heightened awareness of space, shattering physical confines while simultaneously expanding notions around identity and presentation. Her songs, a mixture of pansori—a traditional Korean genre—and electronic music, are captivating and spiritual. For her, they are an invocation of the goddess. In 2017 she was the recipient of the City of West Hollywood’s first grant for transgender artists, with which she developed DoYou: Migration of the Monarchs, a dynamic show incorporating cabaret, burlesque, butoh, kabuki, pansori, and various elaborate costumes. Describing herself on her website as an “avant-garde vaudeville artist,” Yozmit has performed in New York, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, London, Paris, Ibiza, Berlin, Vienna, Sofia, and Seoul.

Content warning: mentions of gender-based violence.

Lori DeGolyer: I saw you perform back in 2013 at the Sylvia Rivera Law Project’s Small Works for Big Change event. I remember you in this black dress that became inflated, and you just towered above the audience. That performance has really stuck with me over the years because it was unlike anything [else] I’ve seen. I’m curious to hear how you think about space—and taking up space—as you’re designing the costumes you perform in and engaging with public spaces, like in the case of your WALK performances.

Yozmit: The [costume means] to me outer shell, but it also means power. It’s like a magic coat for me, to bring out whatever that’s inside of me. In my show [DoYou: Migration of the Monarchs], for example, I go through many different characters. Costume helps to create identity, and it gives certain power to the character. I become woman and man, Cyclops, alien, animals, and all those kind of things with the help of all the costumes and outer shells. It also represents the theme of my performances, which is … transformation. We can be anything that we think of. Constant transformation takes place using my body and just changing the outer appearance. Also, the reason I like big gowns and a monstrous, big beautiful costume is [that] it’s kind of like nostalgia about the past. A lot of women wore these very uncomfortable but big costumes in the past, which [were] capturing attention, but they were suffering within themselves.

A big part of my voice as an artist is about gender and identity, especially me being very androgynous, living in this very patriarchal society. Conflict with gender always created a lot of suffering in my early days, but now I see it like inspiration to my art. So, I think about that. I think about women a lot, and sexuality and gender, and how the feminine has been suppressed for such a long time in human history. I wear big gown because as a two-spirit person, wearing a gown is a dramatic statement. Then I like to take up a lot of space because we’re always in this confined space in our mindset or in society. I want to go beyond that, and I want to take as much space as possible with the costume and with my persona and character because I feel like I have all the right to. Also, the reason I like the outside is that’s where I can wear big costumes. [laughs] That’s where I have the space to move around. And I need as much space as possible. Also, outside space is the most expensive set that I don’t have to pay for. [laughs] It’s kind of like going beyond the boundaries of myself, getting out of my mind and getting out of my physical self, as well. Another big thing is—I see a lot of beautiful costumes in fashion, but it always stays in some expensive store, or runway, or museum, and why does it have to be that way? I want to break the boundaries of this art form that only serves the class of well-to-do. It’s kind of like my very rebellious act of breaking that boundary. Art doesn’t only have to be staged in the museum or expensive runway or store, only for those who can afford.

How the WALK performance came about was—it was so random and I didn’t plan anything. I didn’t think about it. I was doing a lot of nightlife cabaret, like theater performance in New York City. Then one day, a recession came and I lost a lot of my nightlife job and my work got cut off, like, half. It was just out of the frustration—because I don’t know what to do with all these costumes that’s not generating income.

LD: They need to be used.

Y: Right! It was a few days before Halloween. I just started wearing this costume outside of my neighborhood in Bedford-Stuyvesant. That’s where I used to live in New York. It was challenging for me to do that kind of performance around that neighborhood because it wasn’t like Manhattan, like a hip part of town. The thing was, it was really mind-blowing for me, how I felt by doing so, and also how people reacted was also very mind-blowing. People were so excited about, “Oh, what is that?” I was expecting kind of a negative experience, but it was so positive and people cheering like, “Oh, my god, you look so great!” They didn’t expect anything like that in that neighborhood, so that created a drama in the space. After that experience, I did another one in Times Square, another one in Union Square. It just kind of became something from that point on without having any exhibition space or not included with curation with any galleries. It just developed by itself, and now it’s going to festivals and galleries and a university. That walk, metaphorically, it took me on a path.

Photo: Kyle Kupres

Photo: Damien Frost

LD: So, you have a background in fashion. How did you make the shift into becoming a performer?

Y: I come from a very conservative Korean culture [and] family where gender role division is very clear—like, male has to be this way and female has to be that way. When I was growing up, male had to be, “I want to be a lawyer, I want to be a doctor or engineer.” I always knew I was artistic, but I couldn’t tell them that’s what I wanted to do. Also, having art training in Korea was very expensive. My family couldn’t afford for me to go to the art training. So, I chose fashion because fashion was like, I can be creative but also, I can make money quick after graduating because it’s commercial work. Making money was important in our family because we are immigrants from Korea. I kind of persuaded them that way. Our family landed in LA from Korea, and then I worked in the fashion business for 10 years. But in LA, fashion wasn’t fashion. It was like serving commercial business for public consumption, making thousands and thousands of garments, and it was kind of meaningless to me. So, I had that conflict about fashion because it was the form that I chose just to get by. It served me quite well, but it wasn’t my dream.

When you first come to America as an immigrant, all you think about is survival, like learning the language and getting the job. You don’t really think about, like, “Oh, what is it that I really want to do in my life?” At the end of my fashion career, I started designing for Korean K-pop stars. That’s when I experienced this world of performance. My mom was a singer in Korea—a frustrated singer because being a singer in 1950s, when she was young, was like being a prostitute in social hierarchy, because that’s how conservative Korea was: the woman married a man and then served as a wife and [by] raising kids. Being an entertainer, that was a big no-no, like, “You’re gonna degrade our family name,” that kind of attitude. So, my mom was a singer and she sang at the American army base in the jazz band, but one day her brother came and grabbed her by the hair, beat her, and she got dragged off the stage, basically.

LD: Oh, my god. Wow.

Y: It’s a very traumatic experience for her, and her dream was crushed by that. Then she married my father and became a normal housewife as she should be. My mom was never a professional singer, but I always see her singing. She sings when she goes to parties with my grandmother, and I was always in the background doing backup dancing. That’s how I grew up. So, when I started working for Korean pop stars I was like, “You know what? I don’t want to design for them. I want to be them.” That’s the kind of trigger point in my life that made me move back to Korea, and I got signed as a pop artist through contacts with the K-pop stars that I’d been working with full-time. It was 1997. I wanted to do something very avant-garde, very gender-bending and electronic music, but Korea wasn’t ready.

Photo: Connor Lee Photography

Photo: HongJangHyun

LD: Did you try to put out an album and it didn’t work?

Y: Yes. For a year I was recording. But the first thing they told me in Korea is, “Do not ever tell anybody that you’re gay or trans or whatever.” It was in the contract. That’s how I started my journey there, and then all of the songs they were giving me was all cheesy Korean pop that I couldn’t understand and sing because it doesn’t represent who I am. I kept constantly getting in fights with the producers because I came from America, so I had a voice and I had opinion, like, “This is what I wanna do.” But the system back then in Korea was like, “I’m gonna make your stuff, so you just be quiet and follow what I tell you to do.” I got beaten up in the recording studio because I wasn’t following their directions. That’s what was happening back then. I just couldn’t carry on. I had bruises in my eyes, and they called me faggot and stuff like that.

LD: Oh, my god. I’m so sorry.

Y: Sorry I’m becoming emotional, but that’s what happened, and it also brings that memory of my mom getting beaten up.

LD: Yeah, there’s definitely a parallel there. That’s a lot of pain and trauma.

Y: Yeah, it’s in the DNA. I didn’t know anything before then, but now I see all this, what has happened to me and to my mother, and now I understand why. So, I came back to America after a year of struggling in Korea, and I started working in fashion again. I decided to do training with ballet and yoga, and then I found some performance artists that I can work with, kind of like a performance master. Then one master got me to another master and then another master. I was in an apprenticeship with amazing, world-renowned artists and educators. I worked with Rachel Rosenthal, I worked with Thomas Leabhart, which is the Étienne Decroux technique from physical theater, which is the teacher of Marcel Marceau. I started studying voice, which is traditional Korean singing, which is my mom’s background. All this training came to me for 10 years. Then I moved to New York to become a performer, and I got a job at The Box. That’s when I actually started my life in New York as a performer.

LD: And you’re working on producing an album now?

Y: Yeah, I am producing an album now. This music thing is taking a long time, but this is very important for me because I realized my mother’s voice is in my DNA, and voice is such a strong form of communication. I believe sound is a primal source of energy, and it can transform a lot of people’s minds. My music and album have to do with my mom’s voice and my heart. It’s my mother in me. Because when I sing, I hear the voice of my mother. One of the songs I wrote about my mother, and the mother that I’m longing [for] is not just my physical mother; I’m longing for Mother Earth or this maternal energy, this goddess to come back to the earth because that’s what I see in the world. There’s imbalance. We put aside this goddess or Mother Earth, the Gaia energy—and that’s why all this imbalance is happening. This is my really ambitious project, using my music as an incantation to bring that energy back as prayer. I want the goddess to come back through my body.

Yozmit will perform in the Freewaves showcase LOVE &/OR FEAR on September 7, 2019.