Xandra Ibarra: Endurance and Excess

Xandra Ibarra, Colonial Peeps, 2016, video, 4:02 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Xandra Ibarra’s practice of endurance emerges as a generative strategy with the potential to locate pleasure and excess within states of fatigue, emptiness, and a condition of stuckness—or as Ibarra puts it, “fuckedness”—that Ibarra maintains comes with the burden of representation placed upon racialized artists.

As we prepared for Ibarra’s upcoming New York City solo exhibition of work extending across sculpture, video, and performance at Knockdown Center in Queens, we discussed why she identifies as a cockroach, the ways that endurance manifests in her work, and how she turns to approaches that favor illegibility and false endings as strategies to exhaust or undermine representation.

Alexis Wilkinson: As an entry point to your larger body of work and its relationship to conditions of repetition, exhaustion, failure, and attendant strategies of endurance, I thought we could start with the figure of the cockroach. How did you arrive at this figure?

Xandra Ibarra: It’s strange but I didn’t one day decide it was the perfect abject figure. It sort of just kept reappearing, and so I let it have its way with me. I began to read some entomology texts about cockroaches—you know, just boring things like taxonomy, categorization, things like that. Once I began reading about the biological, I became a bit more interested. I learned that, not unlike some reptiles and other vertebrates, it shed its skin. The materiality of the cucaracha molting its exoskeleton yet appearing the same after doing so became central to my critical interrogations of how one might endure life. I was coming to these ideas in 2010-ish or so and began to obsess with it a bit. I began to talk about myself in terms of being a cockroach; I became cockroach-identified. You can do that when you’re queer, you know. People are just, like, “Oh, okay, you’re a cockroach, okay, cool.” [laughs] No, but really. Later I found that there was an archive of Chicanos and Chicano artists who were also cockroach-identified.

AW: What artists were identifying as cockroach?

XI: There’s Oscar Zeta Acosta with the novel The Revolt of the Cockroach People and also Cyclona, a Chicanx LA drag/punk superstar named Robert Legorretta. Cyclona also later joined Asco, a Chicano punk/art collective started during the 1970s in Los Angeles. Robert/ Cyclona is also from El Paso [TX], my place of birth, which is exciting to me.

AW: Were they also dealing with the sort of endless repetition of shedding its skin, or taking up the cockroach as a racialized signifier of national contamination?

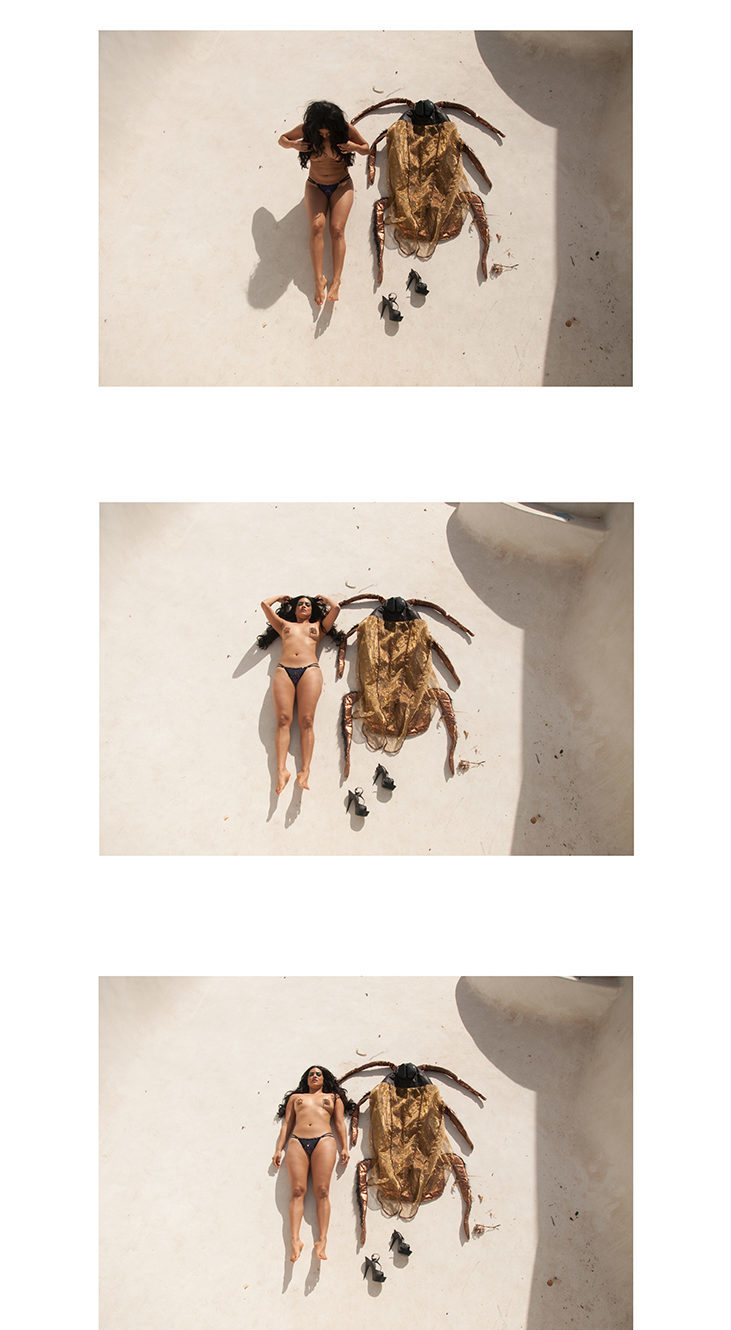

Xandra Ibarra, Ecdysis Triptych, 2015, from the photograph series: Spic Ecdysis, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

XI: I think they used the cockroach as a symbol of contamination: visual and racial excess. Asco was refusing the “politically correct” or respectable Chicanos and also white heteropatriarchy, displacement, and slew of other things …. They did this through abject performance/photographic/graffiti strategies. But Cyclona’s first play was titled Caca-Roaches Have No Friends.

AW: Was the performance and later video F*ck My Life the first time the cockroach manifested/appeared in your work?

XI: Yes, it was.

AW: In F*ck My Life, you “killed off” your burlesque persona La Chica Boom and emerged as cockroach. The Spic Ecdysis photograph series illustrates you performing/enacting the molting process, lying next to the costumes you used when performing as La Chica Boom, your shed skins. The cockroach costume was recently shown in a sculptural presentation with a vacuum element. Can you talk about how the vacuum carries the ideas in this series forward?

XI: Yeah, sure, I can talk about that. The sculpture, in the show you most recently curated in New York City, includes a cockroach costume I made, enclosed in a vacuum-sealed bag atop a light box. A pest-control vacuum sucks the air from the costume in the bag every half hour and then releases it. It takes me some time to choose materials or to choose things like this vacuum. It’s not always about texture, color, lines—for me ideas/concepts usually transcend the material. A vacuum is a space devoid of matter, an emptiness of space, a space where air has been partially exhausted. It’s emptiness, a void, but it’s also a household appliance. The poetics of the definition of vacuum and how it so beautifully communicates the burden of representation for racialized artists—specifically that racialized signifiers are often overdetermined and emptied/exhausted/vacuumed of any specific meaning, and that racialized artists are “speaking for” this imagined fixed racial group. There’s this idea that racialized artists are required to push for better and proper forms of representation and visibility. I am not interested in doing this. I am invested in examining the bond to these signifiers, how it feels to be the excess, how it feels stuck/the same, as opposed to change. And I am sitting there/here, dwelling with the problem of this fucked life, like, forever. I am lingering in its resonances to see if I can find other ways of expressing this way of being through sculpture, video, and performance. Ultimately my goal with these vacuum works is to produce the affective dimensions of being fatigued, fucked raw, emptied of matter, never reaching completion. While this might sound depressing to most, to me it’s a vibrant site of inquiry precisely because there are so [many] ways in which I can explore the affective dimensions of [being] excess and sometimes, oftentimes, they are pleasurable.

AW: Yeah, locating pleasure feels so important within the work, and, life …. I think this brings us back around to what can be learned from the cockroach in terms of endurance. You’ve talked about endurance—as opposed to refusal or liberation—as the quality needed to survive as a racialized body.

XI: Yes, I think of racialization as it is linked with other structures of power as a “fucked” condition. It’s not something that can be restored. It’s a practice of endurance. Exertion, I used to think, led to failure, a failure in an already fatigued state of performance. I don’t think of refusal or liberation as options because that seems too easy, and it’s not possible to be liberated or to refuse everything; it’s more complicated than that. Sometimes there’s sensuality, pleasure, unknowability, and so much more in states of fatigue. During my work on F*ck My Life [the performance] and Spic Ecdysis [the photo series], I was thinking through the ways in which raciality was projected onto my body and the way it controlled the terms of legibility. I mean, it still does, for me, as a performer and a racialized person. I felt/feel misrecognized not just in performance but in my life in dealing with institutions, people, the state. I felt stuck, like the cockroach, like I could never change—I would always stay the same contending with illegibility. I was using my excess as a site for pleasure in my early work as La Chica Boom, but sometimes it felt like a string of endless disciplined realities. Since I took on explicit, abject, and humorous forms of Mexicanidad (spictacles), sometimes the illegibility to audiences felt like a failure, like a condition. I waver between feeling like I am stuck within and interpolated by fucked life without redemption, and other times I invite the illegibility, like maybe I don’t need to respond to the mandate to be transparent! It’s a fucked life, but I think I understand its radical potential. It might be a beautiful fucked life, too.

Xandra Ibarra, performance view of F*ck My Life (FML), 2012, [courtesy of the artist]

AW: Right, humor. There’s so much humor and pleasure underlying so much of your work, which is what makes it so brilliant, I think, but—in the La Chica Boom Spictacles, humor opened up space for misreading … as you said, illegibility. It feels like you are deploying a more purposeful illegibility, or opacity, in video works like Colonial Peeps [and] Turn Around Side Piece. Are these gestures to control the terms of your legibility?

XI: Yes, I think so. For example, in She’s on the Rag, I purposefully approach opacity with humor. I offered, and still do, my uterine lining/the trash of my body/my biomaterial to engage with people online. Like, I am online cruising, looking for connection/belonging and a way to continue with abjection/deviance but without racial transparency. I am offering my body, but you can’t see me. In terms of the video works you mentioned, I am trying to rethink the gaze as expectation, through boredom, and the banal terror of how one might anticipate being perceived or recognized externally. Is there a way to create a politics of daily violence that also contends with sensuality? I think so.

AW: And then there are works that point to an ending: Se Acabó and Ya Estuvo reference an end or a conclusion in their titles [That’s it; Enough; It’s over; It’s done; I’ve had enough], and with the nipple tassel, which gets [revealed] at the end of a striptease. Se Acabó is a sculptural object, these two massive nipple tassels made with leather and horse hair, making this amazing sculptural object that is somewhere between a strange terrain and a reference to the body, sitting in an exciting place between representational and abstract. Ya Estuvo is a two-channel video. One side shows the back of yellow heels clicking, and the other side shows a chest bouncing, nipple tassels twirling in this ongoing, repetitive motion …. I imagine [that] when it’s displayed, the video plays on an endless loop, undermining or negating any actual conclusion. Can you expand on the tension between ending/false-endings in your work?

XI: The final reveal of a traditional striptease performance lays bare the breast decorated with nipple tassels. Both of these works reference this final reveal in a striptease, but also [in] the ongoing claim to an end, conclusion, or a closing. In the video, I capture the back of the heels as they move up and down, clicking to support the bouncing of the breasts to twirl the tassels. The repetition is endless because the video is looped, so in effect the movement of heels, the bouncing breasts, and twirl of the tassels are never-ending. They are the final reveal, but they reveal nothing [except] the repetition of finality or the lack of finality. I guess you could say I am refusing the end, staying with incompleteness, exhausting representation, and creating pathways for becumming … por vida. [laughs]

Xandra Ibarra, Ya Estuvo (still), 2 channel video, color, sound, 1:03 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Energy Structures” Spring/Summer 2019.

Alexis Wilkinson is a curator working across dance, performance, and visual art. She is currently the Director of Exhibitions and Live Art at Knockdown Center in Queens, NY, where she programs and produces interdisciplinary exhibitions, performances, and events. Recent curatorial projects include Extremely absorbent and increasingly hollow, Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, NY (2018), Chloë Bass: The Book of Everyday Instruction, Knockdown Center, NY (2018), A Collection of Slow Events at The Luminary, MO (2017), In Practice: Material Deviance at SculptureCenter, NY (2017), objects are slow events at the Hessel Museum, NY (2016), and Matter to Whom? at the Judd Foundation, NY (2015). She has also organized exhibitions and performances for Abrons Art Center, New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA) NY, and A.I.R. Gallery. Alexis holds an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College and a BA in Cultural Studies, Dance, and Art History from the University of California, Los Angeles.