Witnessing & Community-Making in Bouchra Khalili’s Essay Films

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, installation view, 2008-2011 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

“Who is the witness? The one that still speaks beyond death? The one who speaks for him and for those who can’t speak anymore? And those who are silenced?” These questions surface directly and indirectly in Bouchra Khalili’s essay film Twenty-Two Hours (2018). Moving beyond the genre of documentary, the French-Moroccan artist’s 43-minute essay film revolves around a historical episode: Jean Genet’s two-month visit to the US in spring 1970 in support of the Black Panther Party (BPP).

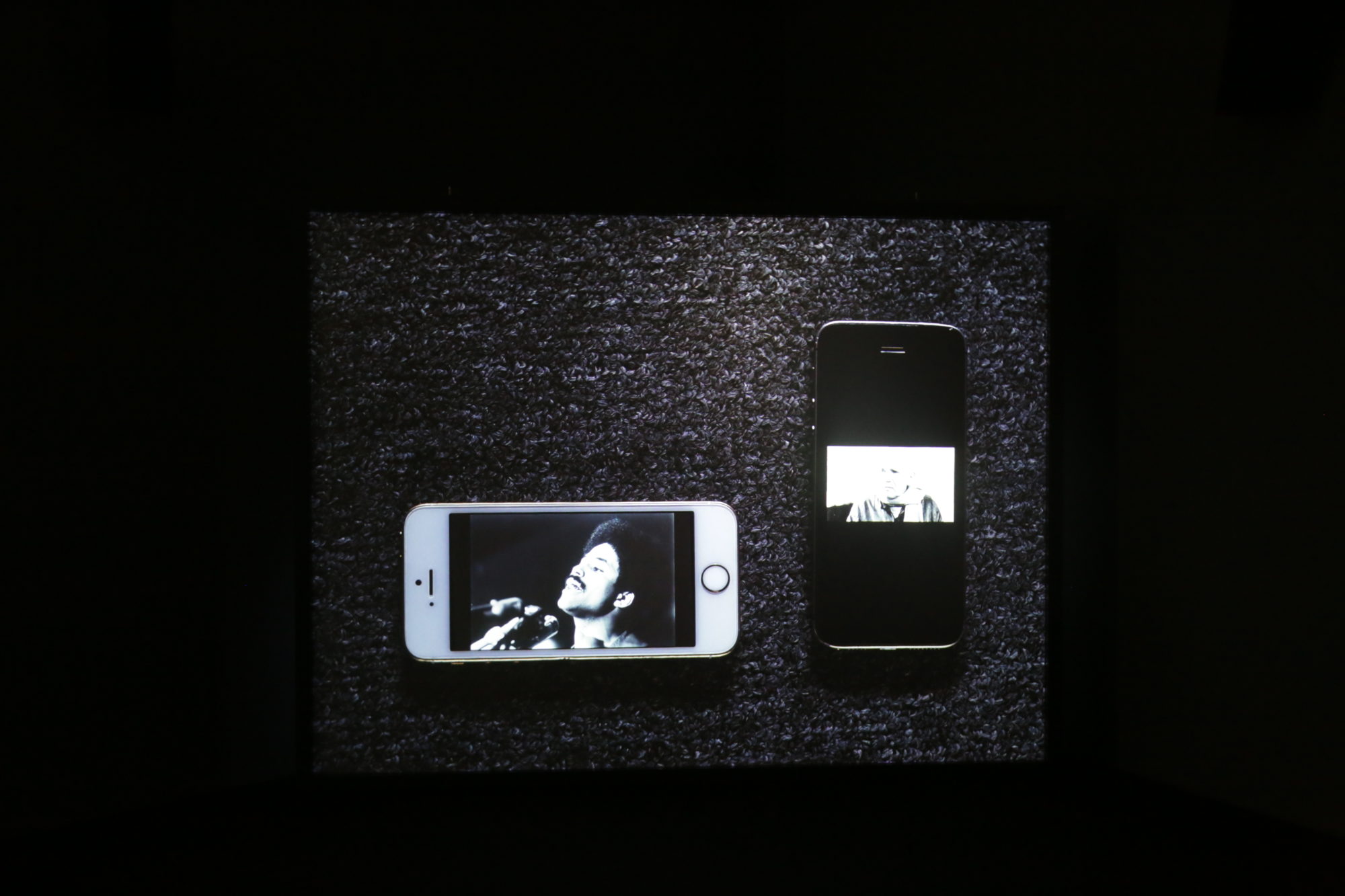

“Witnesses”—some from the present-day and others historical—to this chapter in the BPP’s history appear throughout the film. Two young African American women (Vanessa and Quiana) who are also amateur actors from Boston engage in storytelling around this historical episode. Doug Miranda, a former BPP member, serves as a contemporary witness to Genet’s visit. Miranda was involved with organizing the French intellectual’s stay in the US at the time. These testimonies are complemented with documentary footage, presented in the film via the screens and cell phones of the protagonists. Vanessa and Quiana browse through the material and act as film editors, navigating the path of the film and interpreting the past, thereby functioning as “editors-cum-storytellers.”1

Bouchra Khalili, Twenty-Two Hours (still), 2018, digital film, color, sound, 45 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

French poet and playwright Genet repeatedly stood in support of social movements during the late 1960s and 1970s. His solidarity with the BPP and subsequently with the Palestine Liberation Organization, and his sympathy with the liberation struggles of the German Red Army Faction, offer only some of the evidence needed to understand Genet’s self-proclaimed passage from intellectual to activist. Centrally, he also stood in solidarity with Algerians living in France as immigrants, and he repeatedly advocated for France’s obligation to question its colonialist history, notably after Algerian independence in the early 1960s.

In Prisoner of Love (a memoir-style book published posthumously in 1986) Genet recounts this later phase of his life, which was marked by his engagement in civic and anticolonial struggles. Abandoning his roles as scholar and playwright in response to 1968 and worldwide liberation struggles, Genet acted as a poet-activist and an advocate for human rights. The questions raised in Twenty-Two Hours and the role of Genet as an activist-intellectual are all the more relevant following recent global movements such as Occupy and Black Lives Matter. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale’s BPP aimed at “policing the police” and demonstrated a troubled relationship with the media. More recent movements operate from a radically different understanding of publicity and argue for a systemic critique, combined with an expanded notion of solidarity that engulfs race, gender, and religion.

Bouchra Khalili, “Twenty-Two Hours (still), 2018, digital film, color, sound, 45 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

In the fashion of European cinema engagé, Khalili understands filmmaking as a civic and democratic act creating space for encounter and nonhegemonic knowledge. The cinema of historical avant-gardes was directed toward finding radical possibilities in the construction of history through agitation and propaganda, and by using disparate shots and estranging montage. In contrast, neo-avant-gardes engaged with this legacy while responding to the changing conditions and stakes of film production, as well as to the global waves of decolonization struggles. Khalili’s fascination with the later movement—first and foremost a generation of white male European filmmakers, including Pier Paolo Pasolini and Jean-Luc Godard—is striking at first. Much as Genet did, though, Godard dedicated his work from 1967 through the 1970s explicitly to class struggle and decolonization. This decision led Godard to the foundation of the Dziga Vertov Group alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin (and others) in 1968. Taking up avant-garde impulses, Godard and Gorin’s cinema vérité aimed at transforming the medium at large into a radical-militant endeavor, notably by questioning film production’s complicity with capitalism and bourgeois subjectivity rather than just its aesthetic and distribution. Both the artistic and political legacies of Genet and Godard inform Khalili’s understanding of film, as well as the agency and roles of the artist in society.

Genet’s support of the BPP and his visit to the US in spring 1970 was initiated by the BPP International Section launched by Eldridge Cleaver. Forced to enter the US illegally thanks to previous criminal convictions in France, plus authorities’ knowledge of his association with the communist party and his homosexuality, Genet eventually spent more than two months touring American universities side by side with the BPP. His infamous speech at Yale University on May Day 1970, as demonstrated in Khalili’s film, is not to be understood as Genet speaking for the party. Rather, it was the performance of a script—and his unconditional submission to a cause. The BPP and Genet shared an idea of solidarity informed by their Marxist and radical democratic interpretations of politics.

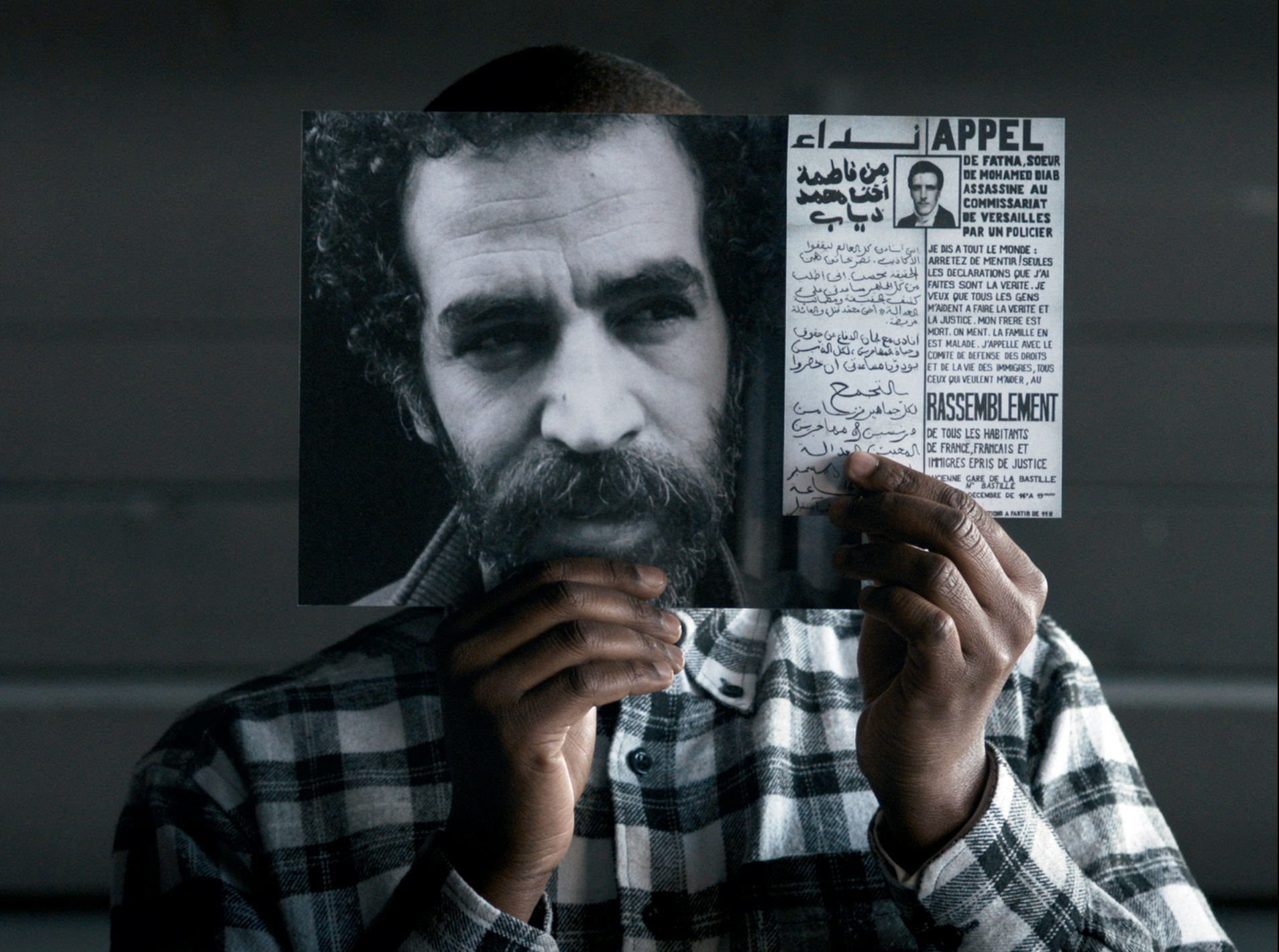

Bouchra Khalili, “The Tempest Society (still),” 2017, digital film, color, sound, 60 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

The topic of solidarity appears in numerous Khalili films—for instance, in The Tempest Society (2017), a work commissioned by documenta 14 and recently presented in a solo show, Poets and Witnesses at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (March 21–August 25, 2019). It revolves around three Athenians discovering the history of a theater group, initiated jointly by French students and North African emigrants, in Paris during the 1970s. The Tempest Society displays and becomes a space for collaborative learning, understanding, and the making of sense about the past and the present, the general and the individual. Similarly, in her earlier Mapping Journey Project (2008–2011), the artist assembled eight stories of routes undertaken by refugees. Each episode reworks a physical map: in the film a hand disconnected from its body draws a route of displacement while narrating a personal journey. The direct language used in these stories contrasts starkly with the metaphorical manner more commonly advocated by Western European narratives in the discussion of migration. As counter-narratives the journeys retraced and thus re-enacted in this work serve as performative appropriations.

Vanessa and Quiana, the two present-day “witnesses” in Twenty-Two Hours, not only discover the BPP’s and Genet’s history but also enter into a conversation about present conditions and their own representation. As in her earlier works (for instance the Mapping Journey Project) Khalili’s casting essentially builds on careful and collective thinking on representation. Scripted and edited in an “organic way” (as stressed by the artist’s sensibility toward her cast), her films materialize personal encounters in a sort of collective learning. For the artist, a mutual understanding of the editing process is central to providing a sense of orientation for all participants. Although the internal organization of Khalili’s films (the chronological shooting and editing processes) is directed toward clarity and transparency, the viewer experiences the works as fluid spaces that continuously shift authorial positions, confounding “witness” and “narrator,” information and interpretation.

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, installation view, 2008-2011 [courtesy of the artist]

Marked by a seemingly irresolvable double status, the figure of the witness is caught between being both an object of information (or a “trace” to be read) and a narrating subject. This aporia regularly surfaces in contemporary art practices concerned with witnessing—for example, the work of Lebanese-British artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Although concerned with a different method and subject, Abu Hamdan engages with decolonial, counter-hegemonic knowledge production and community-making in his work, and he focuses on the material and political aspects of speech counteracting contemporary means of state policing. Abu Hamdan is part of Forensic Architecture, a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London. The agency’s “investigations” often take the shape of complex digital models that draw upon a multiplicity of sources and data sets, often in collaboration with nongovernmental organizations. In a previous issue of ART PAPERS, Rayya Badran noted that Abu Hamdan’s investigative sound installation Saydnaya (the missing 19db) (2017) “summons and synthesizes a confluence of voices, giving meaning to their silencing, and occupying the spaces in which they might echo.”2

The research agency, especially through Abu Hamdan’s work, bolsters a shift away from singular testimony with an insistence on empathy. Instead it pushes toward an institutionalized politics of human rights, providing forums for thus far unheard voices, wrapped in a conceptual, technically driven aesthetic. Ultimately this presentation feeds into unbridled desires for technicity in times of networked cognition, assuming that a position outside of this logic is not to be upheld. “Witnessing” (here in the form of the “ear witness”) renders marginalized knowledge visible and is occupied with providing a protective space and structures of support to its fragility. More importantly, though, sense-making is redirected at the narrating subjects themselves, supported by artistic research and assemblage of evidence.

It seems that the figure of the intellectual as outside of society (Genet, who continuously framed himself as a militant or vagabond) has, in more recent practices, morphed into that of a collaborator or facilitator. Instead of disassembling the public sphere and its institutions, artist Bouchra Khalili’s essayism and Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s investigations are concerned with assembling communities.

Christoph Chwatal is an art historian and critic based in Cologne and Vienna. He is a doctoral fellow at the a.r.t.e.s. Graduate School for the Humanities at the University of Cologne.

References

| ↑1 | Bouchra Khalili, “Blackboard,” in Blackboard, ed. Bouchra Khalili and Laetitia Moukouri (Paris: les presses du reel, 2018), 46–49. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rayya Badran, “Lawrence Abu Hamdan: Terrain of Auscultation,” ART PAPERS 41, No. 3 (Fall 2017), https://www.artpapers.org/lawrence-abu-hamden |