Lawrence Abu Hamdan, “Rubber Coated Steel,” 2016, video still [courtesy of Maureen Paley, London]

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Share:

In his seminal book A Voice and Nothing More (2006), Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist, and film critic Mladen Dolar places the human voice at the center of our political life. He stipulates, in a chapter dedicated to the politics (and antipolitics) of the voice, that political life historically resorted to “the living voice [de vive voix]” in order to animate and indeed render effective texts—or, as he puts it, “dead letters”—in religion, the legal system, and education, all of which are institutions that govern our lives in community. In demonstrating the historical importance of the voice, Dolar explains that without it, a sermon would not be instantiated or disseminated, a tribunal would probably be corrupted, and teaching or learning would remain unfulfilled. In all these rituals, the voice is needed to enunciate and perform the pertinent texts, even if it does not add meaning to their content. The text, whether scripture, legal document, or dissertation, comes into existence for Dolar only if it is enunciated by a living voice.

Dolar discusses the role of the voice’s power in its historical (albeit still existing) forms, yet the continually evolving audio technologies available to governments and individuals today are shifting our perceptions and usage of individuals’ vocal powers, and our understanding of the truths or identities that they carry. Lawrence Abu Hamdan, a British-Lebanese artist, self-described “private ear,” and doctoral candidate in the department of Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, has created a compelling body of work exploring the role of the human voice in a world where audio surveillance technologies are ubiquitous yet invisible, and where, amid innumerable imposed physical and geographical boundaries, voices create discernible borders of their own. In rethinking our modes of listening, Abu Hamdan questions how the law listens, how borders and architecture listen, and how technologies are learning to listen.

Satellite image of Saydnaya prison based on an Amnesty International reconstruction

Part of this inquiry is Abu Hamdan’s The Freedom of Speech Itself (2012), an audio documentary that also incorporates in its more recent iterations what the artist calls “sculptural forms of voiceprints (voice-fingerprints)” visualizing the frequency and amplitude of two different voices saying the word “you.” The subject of the work is the practice of forensic speech analysis implemented by the UK Border Agency (UKBA). In order to determine whether asylum seekers are telling the truth about their origins or misrepresenting themselves so as to gain asylum, candidates are interviewed by “experts” in the appropriate native language; recordings of these conversations are then analyzed for dialectologically relevant features such as accent, grammar, and vocabulary to determine the authenticity of the individual’s claimed origins. This mechanism considers the voice to be the primary document that reveals the “truth” about where a person is from. Abu Hamdan’s 30-minute composition challenges that assumption. The work includes a case study; interviews with asylum seekers, phonetic analysts, and lawyers; and informal, often funny banter with the artist’s translator, whose own personal trajectory speaks of the multiple accents and voiceprints a singular person can have or adopt over a lifetime. Although the interviews address urgent and sometimes devastating issues, there is a levity to this documentary, which is infused by unscripted humor and kitsch delivered in the form of morning radio jingles. These brief but captivating moments emphasize the absurdity of the claim that a voice cannot be plural in its cultural and geographical identities.

Amid the observations of linguists and sociolinguists interviewed by Abu Hamdan is the voice of a Palestinian asylum seeker named Mohamad, who was living in the UK when his speech was subjected to the UKBA analysis. Mohamad, whose story we hear throughout the documentary, was labeled a Syrian on the basis of a single phoneme. This case, like many others, reveals a prejudicial judgment on speech analysis in relation to asylum seekers. Mohamad’s voice, so received, is divorced from its own truth, assigned to a territory it doesn’t belong to. Zeroing in on Mohamad’s experience, the documentary shows that the very medium of speech, and all the identity it carries with it, can be used against those who employ it. Today we are so accustomed to relating the voice to political resistance, using catchphrases such as “raise your voice” and “let your voice be heard” to motivate popular dissent; despite the power traditionally assigned to “speaking up,” the voice can just as easily be instrumentalized against people who refuse to conform. What Abu Hamdan suggests, then, is that we are not free to choose the way we are heard.

“What is the legal status of our voices? … And is there any law that stipulates how our voices should conform with our borders?”

-Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Saydnaya (ray traces), 2017, exhibition view, inkjet prints on acetate on overhead projectors [images courtesy of Lawrence Abu Hamdan; courtesy of Maureen Paley, London]

Toward the end of The Freedom of Speech Itself, Abu Hamdan asks: “What is the legal status of our voices? … And is there any law that stipulates how our voices should conform with our borders?” These questions emerge in his subsequent work Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley (2013), a 15-minute audio essay and audiovisual installation that looks at how the minority community of the Druze, who inhabit the strictly controlled border regions between Palestine/Israel and Syria, complicate the relationship with and ultimately transgress physical boundaries through the use of language and voice. The Shouting Valley, Golan Heights, was named for its advantageous acoustic properties, which enabled members of the divided community to communicate with one another across heavily land-mined, fenced-off areas by shouting from either side of the border to exchange news.

The video opens with an ominous high-pitched static sound, as if he had close-miked the plug of a stereo; as it subsides, a male narrator begins to speak, his voice treated with a tinny, echo effect, as though to create the impression that he is speaking from the depths of a damp tunnel. Various recordings of people shouting across the valley play over a mostly blacked-out screen, interrupted only by short, wobbly flashes of video footage showing the region and the community. This choice to provide only occasional fragments of visual material emphasizes the importance of the voices, languages, and sounds in navigating the culture and geography of the disputed territory.

Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley also considers the Druze voice as it functions within the confines of the Israeli military court system, where Druze soldiers—Arabic-speaking citizens of Israel—serve as translators. In Courting Conflict: The Israeli Military Court System in the West Bank and Gaza (2005) sociologist Lisa Hajjar notes that after speaking to these soldier/translators she came to understand a pattern in the military courts that rendered the Palestinian defendants “objects of legal transactions rather than subjects vested with legal power to act on their own behalf.” According to one specialist interviewed by Abu Hamdan, for instance, a lot of crucial information is withheld from defendants during trials in which Druze soldiers translate for Arabic speakers in custody. Abu Hamdan thus recruits such Druze voices as those of “experts,” once again embedded directly within the context he is studying. The legal status of the voice in Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley shifts between modes of transgression and complicity: it is deployed to circumvent the jurisdiction of the border, and is also used as a way to dislocate the intended meaning from its translation—those acts of agency for a minority enclosed by natural and colonial borders. By shouting to loved ones across the perimeter of the occupied Golan Heights, or by only partially translating information between a judge and a defendant, the voice becomes the sole tool able to move through these militarized territories. Unlike the physical walls in place, language is anything but static; it can both protect and betray its speaker, and can free just as much as it obscures an individual or a territory.

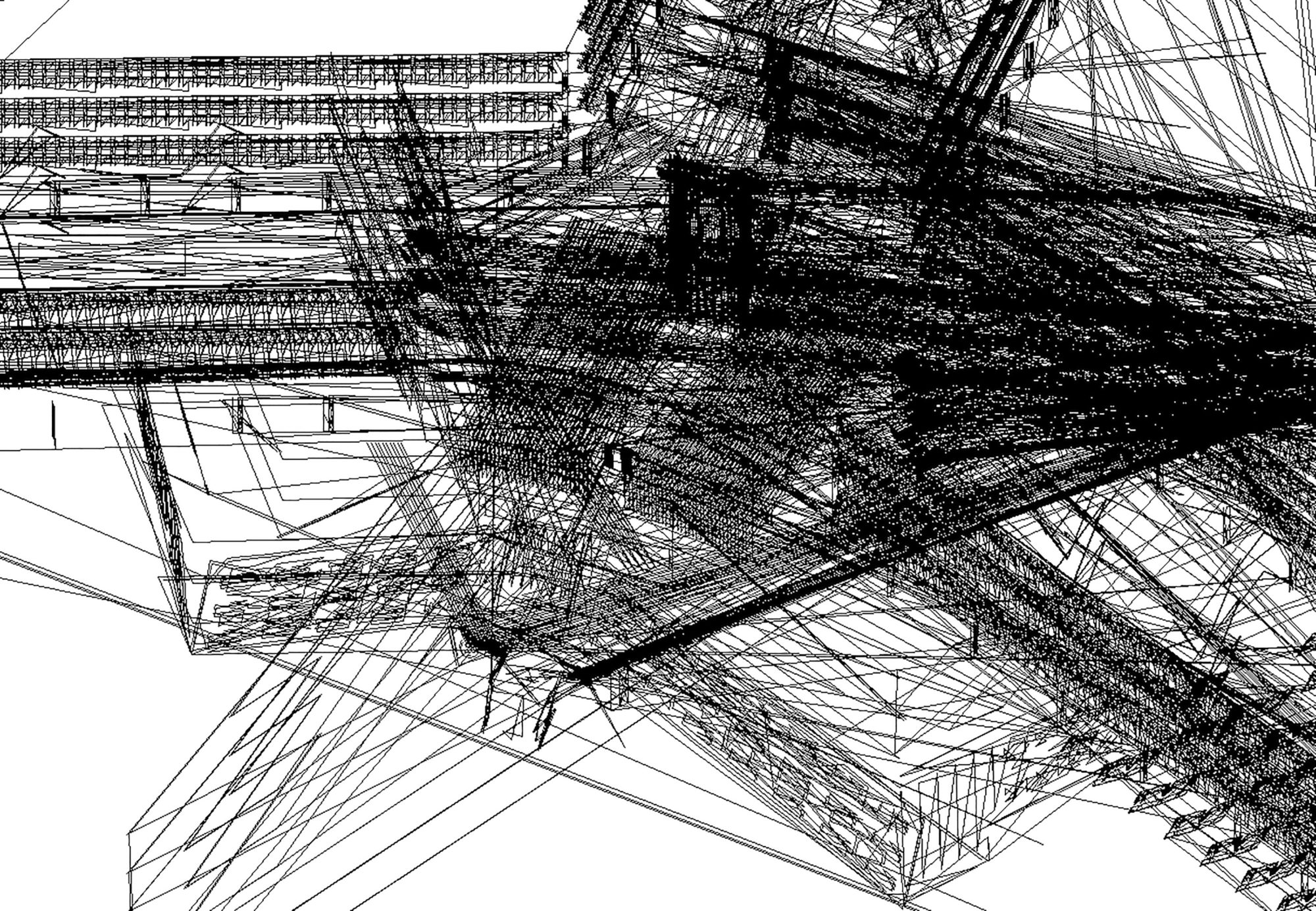

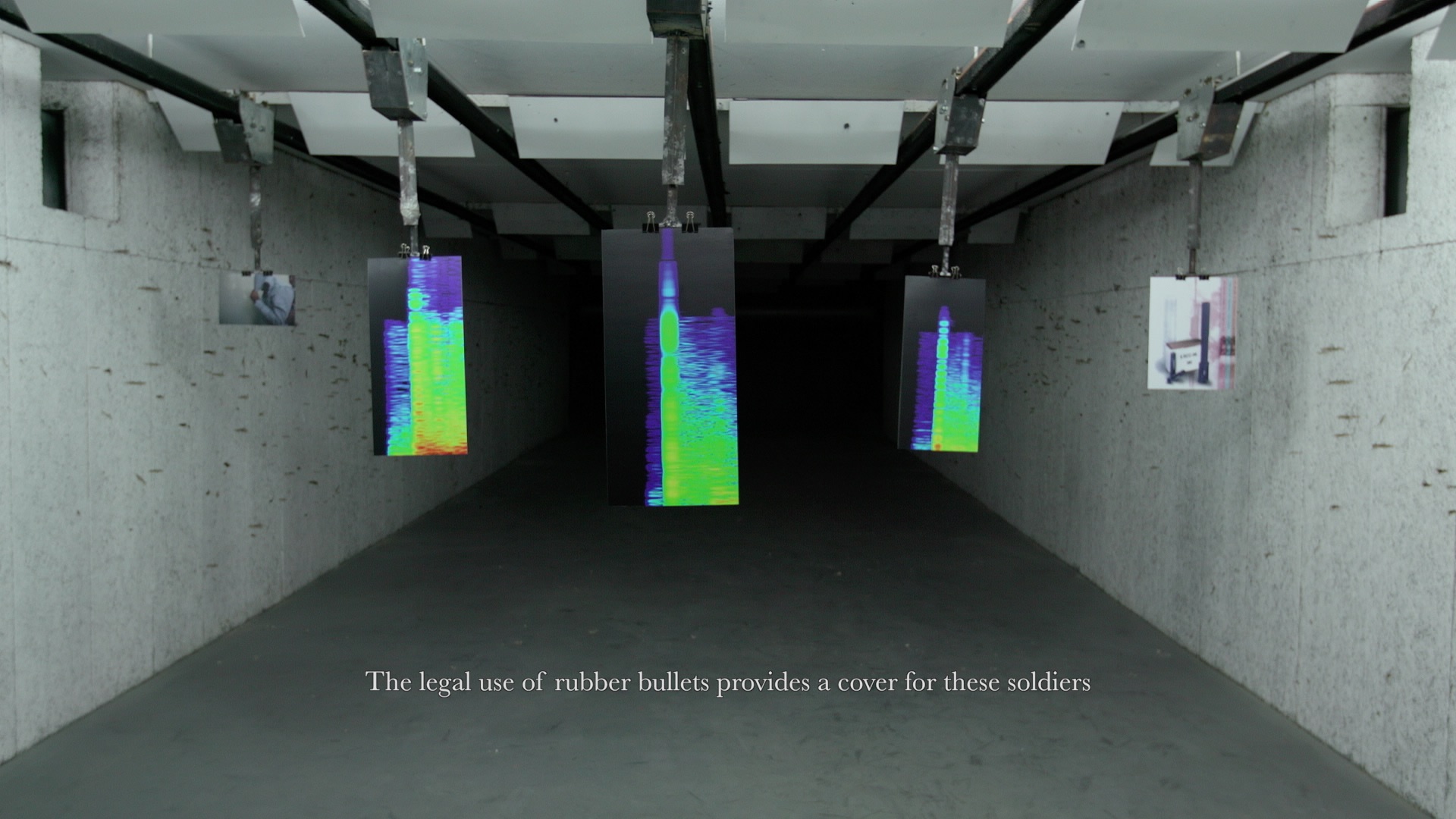

Lawrence Abu Hamdam, Earshot, 2016, installation view [photo: Helena Schlichting; courtesy of Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, and Maureen Paley, London]

Abu Hamdan’s longstanding interest in the legal role of the voice—and in how the law listens—has contributed to an artistic practice that is studied in science, technology, and architecture. Informing this technical approach is the artist’s use of first-person testimony and interviews, materials that allow his work, and his viewers, to navigate complicated geographical, theoretical, cultural, and emotional terrains. His recordings, projects, and installations combine documentary, forensic, and highly personal impulses; these methodologies also feed into his practice as a “private ear,” in which he applies his analysis of sound to collaborations with humanitarian and human rights organizations focused on the Middle East. For Earshot (2016), an exhibition at Portikus, Frankfurt, that featured an installation of visualized sound frequencies and a 21-minute video called Rubber Coated Steel (on which I worked as script assistant), the artist again turned to aural memories of contested territories, and to different modes of listening in the spaces of occupation or conflict. Responding to the case of two Palestinian teenagers who were shot and killed in the West bank by Israeli soldiers in 2014, Abu Hamdan became the private ear for Defence for Children International, a nongovernmental organization devoted to the rights of the child. He approached this case first as an investigator, then as an artist.

As the exhibition text explains, Rubber Coated Steel focused on an audio-ballistic analysis of the sounds of gunshots, intended to prove whether the soldiers “had used rubber bullets, as they asserted, or broken the law by firing live ammunition at the two unarmed teenagers.” Abu Hamdan’s techniques included visualizing the sound frequencies produced by the bullets fired, to determine the type of bullets used—and, more importantly, to assess whether there was an attempt to disguise the gunshots, to make them sound as if they were rubber bullets. In addition to the visualizations exhibited at Portikus, Abu Hamdan presented sonic, photographic, and video materials as a body of evidence for a hypothetical trial, involving the victims’ families, lawyers, and witnesses, as well as experts, as a means to explore how sound and silence navigate contested and legal spaces. The script, with its different characters and rhythms, is neither delivered via voiceover narration nor performed by actors; it appears as a trial transcript that must be read by the audience. While the viewer reads, various pieces of evidence appear on panels that move back and forth, like targets in a shooting range. The piece weaves together the real crime and its hypothetical trial, in which the victims’ presence is felt and understood by the conspicuousness of their silence. Both the spectators in the museum and the protagonists referred to in the transcript are exposed to the technical evidence that Abu Hamdan used to determine the veracity of the real incident’s reports. The script incites feelings of both incomprehension and total plausibility as it confronts viewers with testimonies, analysis, and incidents of mishearing that surround the deaths of these two teenagers. We are reminded of the word “silencer,” which is oppressive alone in its direct meaning but is far more frightening, and more consequential, when it is attached to firearms. Turning the oral trial into a transcript, Hamdan almost entirely mutes the piece: viewers hear only the clunky sounds of the targets’ movements and the shooting range’s sonic atmosphere. In Dolar’s terms, the trial becomes a “dead letter,” and the artist’s visual renderings here officiate as the real voices.

Lawrence Abu Hamdanm “Saydnaya (ray traces),” 2017, exhibition view, inkjet prints on acetate sheets on overhead projectors [image courtesy of Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Maureen Paley, London]

This dangerous silence is the central concern of the artist’s recent work Saydnaya (the missing 19db) (2017), commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation for Tamawuj, the 13th Sharjah Biennial [March 10-October 22, 2017). Saydnaya is the name of a small town some 25 kilometers north of Damascus, and the location of one of the most notorious prisons held by the Syrian regime. Cut off from the world and forbidden to media outlets and NGOs, the prison has overseen the execution of more than 13,000 people since the uprising in 2011. Abu Hamdan worked with Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture to research and record the aural memories and practices of the facility’s former detainees. The only available photographs of Saydnaya are aerial views taken by drones; prisoners are kept in darkness or are blindfolded for sustained periods, so their only memories of the facility are aural. Their sense of orientation, as well as their knowledge of new arrivals, beatings, and executions, all came through their ears.

Abu Hamdan conducted interviews and audio and hearing tests with survivors, so as to give shape to the prison’s architectural properties. The resulting artwork stems from material the artist collected through these interactions and shares an interpretation of the survivors’ experiences through an installation housed in a darkened room, not unlike the ones described by former prisoners, whose accounts figure in the accompanying audio essay. As the short recording begins to play, and visitor’ eyes adjust to the obscurity, we slowly start to discern an automated mixing desk placed on the floor and programmed so that its knobs and controllers move autonomously, showing the amplification and reduction of sound on its different channels. Abu Hamdan narrates here, as he did in Freedom of Speech Itself, to provide context and to introduce his interviews with the survivors, whose responses highlight not only the importance of silence in the prison, but the methods through which they used and subverted it. In his audio essay, Abu Hamdan relates these findings to his preoccupation with the politics of silence. As the prisoners etched recognizable patterns onto Saydnaya’s silence, they were better able to understand, and possibly to survive, this prison. Their inhibited eyesight allowed an increased sensitivity in their hearing, a sensitivity many claimed to have lost after they were released. By re-creating the sounds from the prison, and by adjusting them according to feedback from the interviewees about the sound quality and volume, Abu Hamdan has compiled the only existing documents that allow for a viable reconstruction of the physical space.

Lawrence Abu Hamdanm “Saydnaya (ray traces),” 2017, (detail) [image courtesy of Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Maureen Paley, London]

At the beginning of the audio portion of Saydnaya, one of the survivors can be heard saying, “silence is the master.” This phrase also appears in the installation’s automated light box, as the visualization of a 19-decibel drop—rendering what Abu Hamdan refers to on his website as the “drop in the capacity to speak,” and standing as “testament to the transformation of Saydnaya from a prison to a death camp.” The work not only re-creates an incredibly chilling soundscape of survivors’ experiences, but also reclaims their sonic and aural adaptation to the suffocating silence as a way to better grasp a physicality and a temporality that would otherwise be merely vaguely remembered. In other words, Abu Hamdan auscultates silent Saydnaya; the voices of its prisoners function as his stethoscope.

What is particularly absorbing in Abu Hamdan’s works is their substantiation of aurality as a crucial mode of experience, communication, and agency. Often considered as secondary or subordinate to sight, sound here is used as a central medium through which aural or linguistic evidence, testimony, and authorial narration are spliced together to create audio essays, images, and installations that reflect on the multiple roles of the voice. While the works described above include sculpture as well as visualizations in the form of text or sonograms, sound is never an accompaniment, but the primary means through which the artist’s investigative environments take shape. Abu Hamdan’s earlier audio documentaries and his more recent, large-scale installations operate on a shared level of auscultation: of vital listening to the inner workings of otherwise indiscernible systems, symptoms, and tissues. Unlike traditional modes of representation, this use of sound does not seek merely to translate, codify, or replicate a single memory or landscape; it summons and synthesizes a confluence of voices, giving meaning to their silencing, and occupying the spaces in which they might echo.

Rayya Badran is a writer who lives and works in Beirut. She teaches sound studies at the American University of Beirut.