Windows on the World

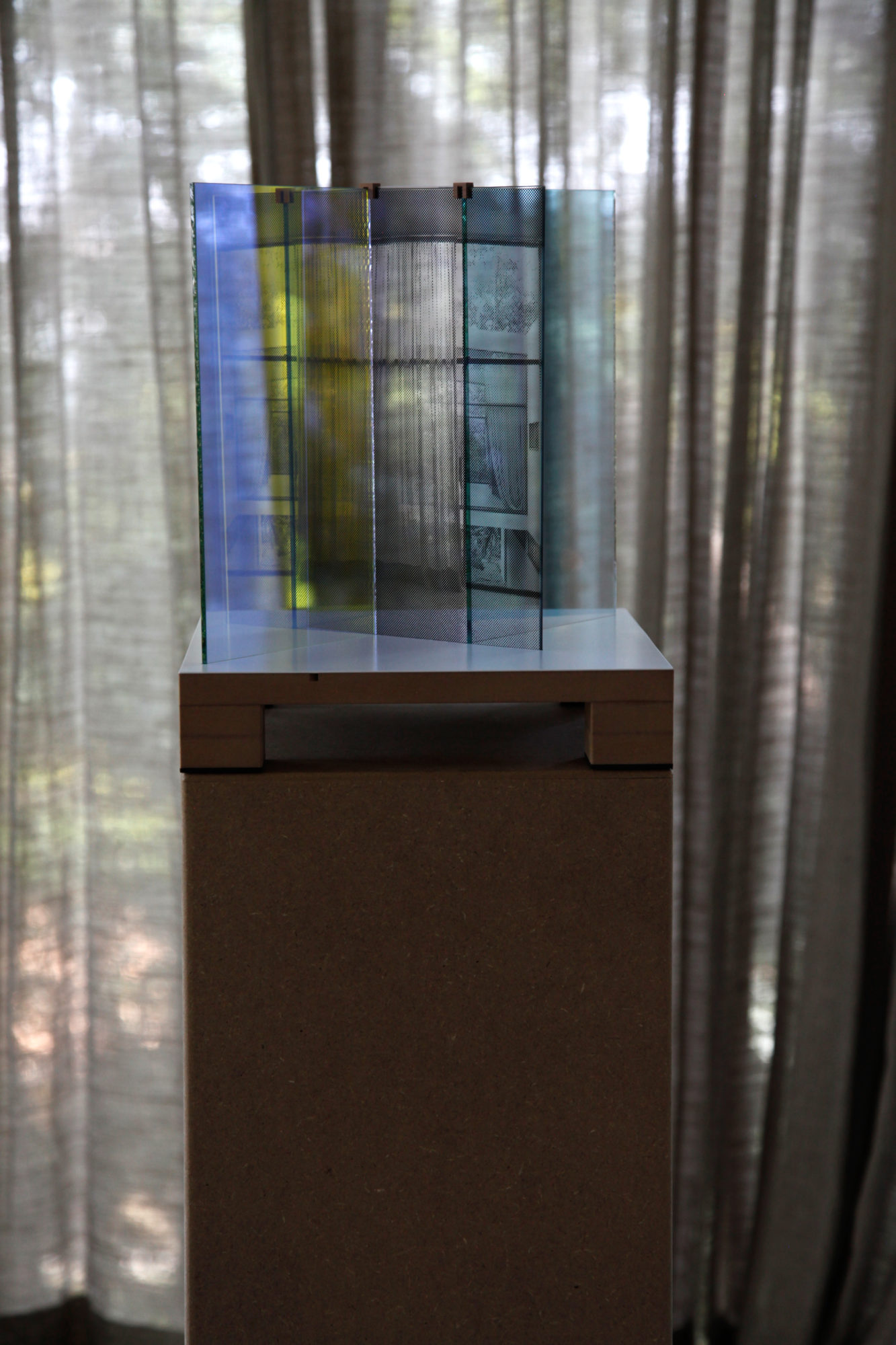

Veronika Kellndorfer, Curtain, courtyard and reflection, 2016, silk screen and dichromatic glass panels, 84-1/2 x 29-5/8 x 69 inches [courtesy of Christopher Grimes Gallery]

Just days before it was announced that Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee would be curating the next Chicago Architecture Biennial, Johnston sat down with Berlin-based artist Veronika Kellndorfer to discuss a decade of fruitful collaborations between Kellndorfer and Johnston Marklee, the architectural firm Johnston cofounded with Lee.

Share:

Their first collaborations revolved around reflection, projection, and swimming pools: one of the SCHOCKEN (2001) installations, for example, is a neon sign piece Kellndorfer made to be placed on a wall above a swimming pool attached to a historic house that Johnston Marklee designed in the Hollywood Hills. Most recently, Kellndorfer portrayed Johnston Marklee’s celebrated Hill House in a book titled House Is a House Is a House Is a House Is a House: Architectures and Collaborations of Johnston Marklee (Birkhäuser, 2016), which presents a series of conversations and artist interpretations of Johnston Marklee’s buildings and projects. Here, Kellndorfer and Johnston continue their ongoing dialogue about representation in architecture, discussing windows, reflections, their shared admiration for Rudolph Schindler, and the role of architectural models in their respective practices.

Sharon Johnston: Let’s start our conversation with a short history of the projects we’ve done together, beginning with No Room, the show I curated with Mark Lee at Christopher Grimes Gallery in Los Angeles in 2008.

Veronika Kellndorfer: I always understood No Room more as an exploration than an exhibition.

Sharon: Christopher Grimes gave us a carte blanche to curate an exhibition in his gallery space. Beyond bricks and mortar, modern architecture in contemporary art is often used as shorthand for current social movements. No Room tracks this trajectory and considers the failure of modernist optimism, followed by postmodern skepticism, and modernist design’s recent renovation into lifestyle fodder, taking into account the turbulent oscillation between the content intended by the artists and the fluctuations brought about through context and time. The assemblage was composed of works of art that employ architecture as a central referent, and a variety of iconic and vernacular furniture pieces that transformed the space. Visitors were encouraged to circulate among the artworks, the furniture, and other interior accoutrements installed in the gallery, becoming part of a complex mise-en-scène. The combinatory nature of No Room meditates on art and space-making, and challenges the contemporary desire for the dholistic and glossy images of both.

Veronika: For the show, you selected one of my key works, The Reconstruction, Part II, which shows Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, reconstructed in 1986. The opaque glass window mirrors the space behind me, the shallow pool, and the travertine wall of the building. I printed two silk screens on glass as inversions—one positive, the other negative—and installed them in a corner of the exhibition space. The already complex interplay of reflections is further complicated by the interference with each other, recalling the experience of a house of mirrors.

Johnston Marklee’s Hill House in “House Is a House Is a House Is a House Is a House: Architectures and Collaborations of Johnston Marklee” (Birkhäuser, 2016)

Sharon: In 2009, Valeria and Pierpaolo Barzan—Italian collectors and founders of DEPART Foundation, based in Rome and Los Angeles—commissioned a piece from you for the garden adjacent to their pool in Los Angeles. We had just renovated their home, called Pine Tree Place. The original 1930s house was owned by the actress Anne Baxter, who had it renovated and expanded by John Lautner on the recommendation of her grandfather, Frank Lloyd Wright, in 1951, including the new pool. In 2010 we added further architectural layers, which included your SCHOCKEN neon sign. Could you talk about how you decided to site the piece, and the importance of the pool and the opportunity for reflection in the surface of the water?

Veronika: Pine Tree Place is the perfect location for SCHOCKEN, part 3, which refers to Erich Mendelsohn’s department store Schocken in Stuttgart, [an establishment that] was demolished in 1960. Fifty years after its destruction, I installed a first version of the store’s neon sign—the original was removed by the Nazis in 1938, and its whereabout are still unknown—on the facade of the Hegel-Haus museum in Stuttgart, exactly opposite the former store. I then produced a larger version of the sign for the site of Pine Tree Place in West Hollywood. The letters were arranged in such a way as to be reflected and mirrored by the water of the pool. In German the word schoken means “to shock,” but it is also the family name of Salman and Simon Schocken, the founders of several department stores, as well as the publishing house that first published Franz Kafka’s Amerika. At night the sign’s lettering creates a very mysterious atmosphere, functioning as pool lighting and at the same time reflecting a complex part of German history in the water surface of the pool.

Sharon: In 2008 you made a piece about Schindler’s Lovell Beach House, and the overlapping spatial dynamics within the work’s picture plane intrigue me. There is the play of the striated foreground, middle ground, and background that works with the grid of Schindler’s glazing mullions; then there are the diagonals of the balcony that cut across the grid and align with the edge of the picture frame. Looking at this piece, one’s perception tends to swing between the single-point perspective of the picture window and a reading of a flat modernist space.

Veronika: My work Lovell Beach House is an ideal example of how architecture transforms into an image. As you said, it is of course not a picture in the Renaissance or Albertian sense. It is not a window to the world; in fact it is quite the reverse: the window pane itself is the picture, together with the traces of habitation, the grid structure formed by the glazing mullions, and the dramatic diagonal of the balcony breaking through the glass. In the foreground one can see a bourgeois interior, in the middle ground the windowpane, and in the background sand and sea. A closer look shows people sitting under sunshades, a couple rolling out a beach mat, sailboats, a wooden lifeguard tower, and a beach tent. The horizon is blurred in the hazy afternoon light. It is unclear where the sea turns into the sky. The atmosphere and subject matter of the work recall Georges Seurat’s Un dimanche après-midi à l’ile de la Grande Jatte. The silk-screen raster of tiny dots burned into the glass is a further reference to Seurat’s pointillism. The interior is divided from the exterior by that thin glass membrane.

Sharon: So the interior and the exterior spaces, along with all the layers between, are compressed methodically onto the surface. But it is not merely compressed, as there is a dynamic relationship between the 2-D space of the image, the glass as an object, and the projective space of the depth in the image that occupies and transforms the space it is exhibited in.

Veronika: What you see is the radical integration of interior and exterior space. I wanted to address the shifting layers within the image, a phenomenon that occurs in almost any window along the California coast—a phenomenon that touches the universal and the specific.

Sharon: The way you describe your piece reminds me of the radical tenets outlined in Schindler’s writings on “space architecture,” which he began almost a hundred years ago.

Veronika: In regard to spatial exploration, Schindler is one of my Californian heroes, and I am moved by how underestimated he was during his lifetime.

Veronika Kellndorfer, Lovell Beach House, 2008, Silkscreen on glass, 3 panels, 115 1/4 x 158 1/2 inches [courtesy of Christopher Grimes Gallery]

Sharon: Architecture in your work seems to be but one of the mediums from which to address the larger issue of space, and pictorial space in particular, which finds its primacy in painting. Could you talk about this relation between architecture and painting, between the threedimensional and the two-dimensional, and between physical and projected space?

Veronika: This question points directly into the center of my work. … I am captivated by the notion of architecture as a projection onto a two-dimensional plan. In painting it is always the projection of space onto a surface—the back-projection of something three-dimensional onto a two-dimensional surface. In the case of Lovell Beach House, I extracted space from an analogue photo taken with a five-by-four camera, and transferred it into another space. The reflections on the glass allow the real space to interact with the printed space. By making use of the transparency of the glass and by not making it opaque, the space behind the picture, which is typically excluded, amalgamates with the printed background and adds another layer to the layers within the overall image. By using highly reflective, transparent glass as an image carrier, I avoid the fixedness of an enlarged photograph representing a house as a static object. My desire is to bring a somehow fluid geometry into rationalism.

Sharon: In many ways, I think your interest in architecture mirrors my own interest in art. Looking at art—a discipline parallel to architecture—allows us to examine our own work from a different perspective. This oblique view is what inspired our work with you and others for the book House Is a House Is a House Is a House Is a House. While our work as architects is focused on core disciplinary issues and tools, our work with artists and our exploration of contemporary art is a chance to look through a different lens, and to initiate other conversations that inform our thinking.

Veronika: I am very curious to hear how you describe your approach to the Hill House. In terms of your process, what comes first? Do you think first of it as sculptural form, or do you think in terms of plans and drawings? For me the Hill House is a very site-specific work with a strong and unexpected quality.

Sharon: In the case of the Hill House, the process was very different from any projects we made before or after. The steep and irregular site was deemed unbuildable by the city, and rather than considering the restraints as policing obstacles, we turned them into design devices. So we created a maximum buildable envelope through studies in drawing, 3-D models, and built models, while engineering a minimal footprint to save on construction costs. In other words, we designed the house three-dimensionally from the outside in, because addressing the constraints placed on the exterior envelope was more urgent than the interior organization. Throughout the early stages of this project, we were integrating the legislative rules of the hillside with our requirements to maximize the occupiable volume and design an efficient structure. Two-dimensional drawings were used to develop plan conditions that had to be calibrated against the volumetric limitations of the zoning laws and the steep slope. While the form of the house—the result of city restrictions and engineering—happened very automatically, we had a parallel interest in creating an object that is both strange and familiar. Hence I am glad that you see the house both as a sculpture as well as something that is very site-specific.

Veronika: I did not know the city considered the site unbuildable. Interesting that, even though you had to work from the outside in, you managed to create that amazing interior space; a space that not only overlooks the canyon but seems to be in touch with the canyon.

Sharon: How the views and apertures relate with the volume is important to our work. Among other reasons, our impetus to create an abstract volume, to erase as much articulation as possible, is to distill the house to a single gesture. So whether you look at the house from a distance or from up close, it is the same. There is no foreground, no middle ground, only background. As a result of this, the view replaces the middleground, becoming almost like one of the walls of the house. The resulting superimposition of the abstract envelope and the hyperreal details of the framed view produces a tension between the flatness of the picture plane and the volume of the room, which we see paralleled in the collapse of image and space within the plane of the glass in your work. To manage these layers, we had to develop different modeling techniques to examine the structure, the overall form and mass of the building, as well as the interior; we used layers of acrylic and a technique of negative printmaking to study the interior volumes.

Veronika Kellndorfer, Curtain, courtyard and reflection, 2016, silk screen and dichromatic glass panels, 84-1/2 x 29-5/8 x 69 inches [courtesy of Christopher Grimes Gallery]

Veronika Kellndorfer, Curtain, courtyard and reflection, 2016, silk screen and dichromatic glass panels, 84-1/2 x 29-5/8 x 69 inches [courtesy of Christopher Grimes Gallery]

Veronika: My 2012 show Abstract Neighbors at Christopher Grimes Gallery in Los Angeles was built around the Lovell Beach House, which was installed as a freestanding glass piece. During the research for this project I found a text Schindler had written in 1947, describing his Wolfe House [on Catalina Island]: “Instead of digging into the hill, the house stands on tiptoe above it. The design consciously abandons the conventional conception of the house as being a carved mass of honeycombed material protruding from the mountain, for the sake of creating a composition of space units in and of the atmosphere above the hill.” Do you think Schindler’s description relates to your approach on the Hill House?

Sharon: There is certainly a visual effect of dynamic equilibrium we were trying to achieve: something balanced, but not a type of harmonious balance in the Miesian sense—a balance that is dangerous, an equilibrium that threatens to topple or roll over at any moment. Schindler has been a pioneer in rethinking the gestalt of hillside building. In many ways, this subject of mass and volume is closely related to the issues of frames and views that we have been discussing, in that the gestalt of the architectural mass is often the first step in situating the conditions for viewing. If designing a building is equivalent to cooking, the process of abstracting the volume is equivalent to marinating, like preparing the food before it is cooked. Designing the windows is the real action—the actual cooking. The openings are what matters most. They are what connect us to the outside and beyond. One technique that I found particularly interesting in Tropical Modernism, your recent show at Christopher Grimes Gallery, was how the planes of glass are assembled in a serrated arrangement, almost as freestanding spatial dividers, approximating an architectural model or maquette. Perhaps you could talk a bit more about how you think about representation and materiality in these three-dimensional works and how your approach to making objects is different from your approach to works that are mounted on or near the wall. When the glass planes begin to approximate an architectural element—a wall or screen—they project new spaces around them, transforming the attributes of materiality and light in the image into something else altogether.

Veronika: Combining glass with vitreous silk screens generates the impression of flickering light, dichroic complementary colors allowing reflections and shadows. The pieces resemble gardens of mirrors, creating a multitude of almost filmic light movements, shadows, and colors [that change] according to the movements of the viewer. [It’s] an almost morphological transformation, [in which] a static object achieves the quality of being ambiguous and unstable. This play of light brings in the cinematic aspects of filmic sequences, and the distilled frames become multipliers that confuse perception and space. The overall effect comes from both materiality and scaling.

Sharon: Perhaps an analogue for [architects] would be how we work between the scale of the architectural model and the built structure. Each tool that we work with—a model, drawing, or photograph—helps us focus our research on different themes that are part of the design development. Our office is a model-building studio, and we work with models through all phases of design and construction. Yet we often find ourselves using photography to reframe these models, to bracket and refine our critical look at aspects of the project. In a way the use of photography helps us to abstract qualities of the overall building in order to refine specific ideas about structure, materiality, or light. Especially since no singular model or drawing captures everything that makes up a finished building, we continually work between mediums, scales, and modes of representation, between “real” materials and simulations, as we build up from the representation of the work to the finished building.

Veronika: This difference in scale creates an abstraction that helps me to step back and take a critical look, just as if my work was by someone else. With most projects I start with models, which helps to clarify whether a projection has to be executed in real space. Very often models turn out to be the missing link in the dialectics of projecting a three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional image and then retransferring this two-dimensional image into another three-dimensional space.

Sharon: I think these issues of scaling and materiality are examined in very poignant ways in your installation Cinematic Framing, at Casa de Vidro in Sao Paolo in 2015. It is fascinating to see how you experimented with the various scales and techniques of representing the house, with the house itself as the backdrop. In Tree House, the image of the facade of the house, including the magnificent curtains visible behind the glass, is printed on a sheet of glass that is then mounted within the room of the house, in front of the actual, full-scale curtains that enclose the room. This doubling and layering of scale, image, and materiality creates such a strong spatial atmosphere between two-dimensional and three-dimensional space. You even experimented with printing on fabric, and these works are then draped around and underneath the house. How did you make decisions here about materials and installation?

Veronika: Cinematic Framing was my response to the precious opportunity to use Lina Bo Bardi’s fragile and vulnerable home both as a place for artistic research and the place where the works distilled from this research could be staged. In Tree House, a photographic image taken from the exterior of the Glass House returns as a glass silk-screen print inside the building. The vitreous screen is positioned freestanding in front of its real counterpart, lifted by the very concrete pedestals Lina Bo Bardi designed for her first exhibition concept at Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo in 1968. Tree House is a miniaturization compared to the size of the real facade of Casa de Vidro. In the atrium, which is an exterior space in the interior of the house, I reversed this relation of scaling and materiality by placing an enlarged, monumental textile printed with the photographic image of the indoor window curtain.

Veronika Kellndorfer, SCHOCKEN, part 3, 2011, neon sign, Los Angeles [courtesy of the artist]

The sign’s lettering creates a very mysterious atmosphere, functioning as pool lighting and at the same time reflecting a complex part of German history…

-Veronika Kellndorfer

Sharon: Beyond the architect’s more traditional tools, we have also developed a technique of collage as part of our conceptual development of each project. By situating our work within the context of a historical image, a referent idea, or an atmosphere that exists outside of or parallel to the work, but informs our thinking, we are able to expand our design research and tools for distilling our thinking around these spaces. We can trace the oblique kind of collaboration over time in the collages to the collaborations in our book House Is a House Is a House Is a House Is a House.We think of the artist portfolios in the book—including portraits by Walead Beshty, Livia Corona, Luisa Lambri, Marianne Mueller, Jack Pierson, Nicolas Valentini, James Welling, and you, specifically—as an invitation to reflect on our work and continue our research through the lens of another artist. In this relatively early stage of our career, we aspired to a book project that would open up new directions of thinking, as opposed to a traditional monograph, which in our minds tends to encapsulate a collection of projects.

Veronika: My contribution tries to emphasize the relation between Hill House and its surroundings. From a distance it looks like a jewel placed in an organic setting. It struck me how the built geometry of a house can relate to the changing geometry of plants. So the diptych is a way to mount photos taken from the botanical garden in Catalina Island with images of the house, like a 35mm film montage of shots from different locations.

Having this chance to look back with you on our history of theoretical and physical exchange on art and architecture, I am inspired with wild imaginations of possible future collaborations. For example, I could imagine working together on real and faked windows as sliding images by adding layers of printed prospects. Another thing I would love to do is to draft a freestanding spatial divider as part of one of your interior spaces, or even to create a whole facade together.

Sharon: I think this would be an exciting next step, to imagine how we could combine our mutual fascination with windows as architectural and visual elements that are physical and functional, but at the same time impart a surreal quality of flickering light and image, mediating interior and exterior space through reflective landscapes of mirrors or filmic shadows.