What is Left Unspoken, Love, installation view, 2022 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta]

What’s Love Got to Do with It? What Is Left Unspoken, Love

Share:

In its presentation of almost 70 works by more than 35 contemporary artists based in North America, Europe, and Asia—including such luminaries of recent decades as Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, and Rashid Johnson—ambition may be the most apparent and sustained quality of What Is Left Unspoken, Love at the High Museum of Art. Organized by curator Michael Rooks, Love undoubtedly represents the museum’s largest-scale attempt at originating a significant group exhibition of contemporary art in at least a decade. (Standout group exhibitions of recent years, such as Outliers and American Vanguard Art, in 2018, have held a broader historical purview and been organized by other institutions. Outliers, for example, was organized by the National Gallery of Art.) In addition to the high caliber and number of artists involved, the exhibition’s ambitions are also signaled by its intellectual and curatorial framing, which divides Love into six thematic sections, presented almost like chapters of a lyrical, philosophical text that audaciously takes on the multiple meanings or valences of love: The Two, The School of Love, The Practice of Love, Loving Community, Poetics of Love, and Love Supreme. Taken together, these factors establish certain expectations about what the exhibition has the potential to achieve artistically, or what it might meaningfully contribute to a public conversation about the topics at hand. To put it bluntly: You get your hopes up.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Perfect Lovers, 1987-1990, wall clocks [courtesy of the artist, and The Felix Gonzalez- Torres Foundation, and Dallas Museum of Art, Texas]

Perhaps thanks to its thematic nature, Love relies heavily upon wall text (presumably written by Rooks, though the attribution is unclear) to reinforce the exhibition’s curatorial structure as viewers move from gallery to gallery. The tone of the expository wall text—installed in the exhibition’s first section, The Two, which focuses, somewhat anachronistically, upon the romantic unit of the couple—registers as oddly generalized and aloof, given the exhibition’s theme. The text claims, for example, that the exhibition’s title “refers to the many situations in which love is unacknowledged or unresolved and to the regret that may follow when people cannot bring themselves to give voice to the words I love you.” The viewer is left with no alternative but to accept this verbose yet vague explanation, despite the lack of further demonstration or refinement of the point. And, for what it’s worth, isn’t this a highly individual experience to impose as the general curatorial framework for an exhibition of this scale? Isn’t some people’s problem that they say I love you too much, too easily?

Of all the artworks in the exhibition, few are as thematically appropriate as Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987–1990), in which two side-by-side, battery-operated wall clocks are initially set to the same time and subsequently fall out of sync as their batteries expire and are replaced—playing out a scenario familiar to most couples. It’s a shame, then, that the work is hung high on a wall, around the corner from the initial gallery’s entrance, and positioned so that viewers could easily pass without noticing it. Other artworks in The Two—such as Dara Friedman’s 2001 video Romance, showing anonymous couples making out in parks in Rome, and a series of photographic self-portraits by artist couple RongRong & inri—prove superficially relevant yet uninspiring inclusions.

Thomas Barger, Love Me, Protect Me Chair, 2018, paper pulp, plywood, two wooden chairs, polyurethane, and paint [courtesy of the artist, and Salon 94 Design]

What is Left Unspoken, Love, Installation view, 2022 [photo credit: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta]

The next section, The School of Love, greatly benefits from the specificity of its focus upon the home and familial love, which provides it with a sense of cohesion and substance lacking in other parts of the exhibition. The centerpiece of this section is Thomas Barger’s sculpture Love Me, Protect Me Chair (2018), consisting of two traditional-looking wooden chairs partially encased within and conjoined by a bulbous structure made of paper pulp, polyurethane, and paint—a baby-blue growth, tender and slightly grotesque, punctuated with gridded perforations that suggest a gingham pattern. Kahlil Robert Irving’s My Grandmother’s Cupboard (Artifact) (2020) similarly evokes sensory and emotional memories of domestic spaces through formal yet vernacular material expression. In Irving’s installation, dozens of black ceramic vessels are assembled in a cabinet to become a poetic sculptural rendering of a Black family gathered together. Patty Chang’s two-channel video Que Sera Sera/Invocations (2013) shows the artist cradling and singing to her infant son in the hospital room where her father is dying, providing an elegiac meditation upon grief, care, and indelible intergenerational bonds. The School of Love section is anchored—both visually within the gallery and, in many ways, art historically—by Carrie Mae Weems’ The Kitchen Table Series (1990), a set of photographs and texts in which the artist depicts herself as a Black woman navigating a romantic relationship and traditional roles associated with race and gender. The relationships between the artworks in this section feel clear, yet richly layered and complex, inviting serious contemplation rather than cursory recognition.

What is Left Unspoken, Love, installation view, 2022 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta]

Elsewhere in the exhibition, however, artworks spin out of context and are connected only by tenuous and occasionally speculative threads. The Practice of Love juxtaposes painter Susanna Coffey’s obsessively varied self-portraits with sculptural works by Wangechi Mutu as part of a poorly articulated examination of self-love. According to the wall text and labels, the “self-image becomes a mirror reflection of the friend or neighbor to whom one’s goodness is directed, ” and Mutu’s mermaid-like Water Woman (2017) is made into “the protagonist of a postcolonial love story.” As in the broad claims about its title at the exhibition’s outset, such grasping attempts at relevance and connection reveal a regrettably superficial level of attention to the rigorous conceptual framing that one expects of an exhibition with the ambitions of Love.

In Loving Community, a section exploring marginalized communities’ struggles for justice in terms of love and friendship, the wall texts’ level of contrivance reaches a high point by claiming “the global AIDS crisis brought LGBTQIA+ and straight communities together in an allyship permeated by love.” It is intriguing to see two of General Idea’s Great AIDS paintings (1990/2019) in an exhibition about love. Their four-letter design does, after all, derive from Robert Indiana’s famous LOVE image—but this gross misrepresentation of the historical realities of the HIV/AIDS crisis as a sort of campfire gathering of mutual support dramatically undermines the gravity and political earnestness with which they are being presented. Admittedly, the sharp curves of the figure in Mutu’s Water Woman, seen in the foreground against those of the letterforms in General Idea’s Great AIDS in the background, makes for a striking sightline—but proximity doesn’t necessarily create meaning.

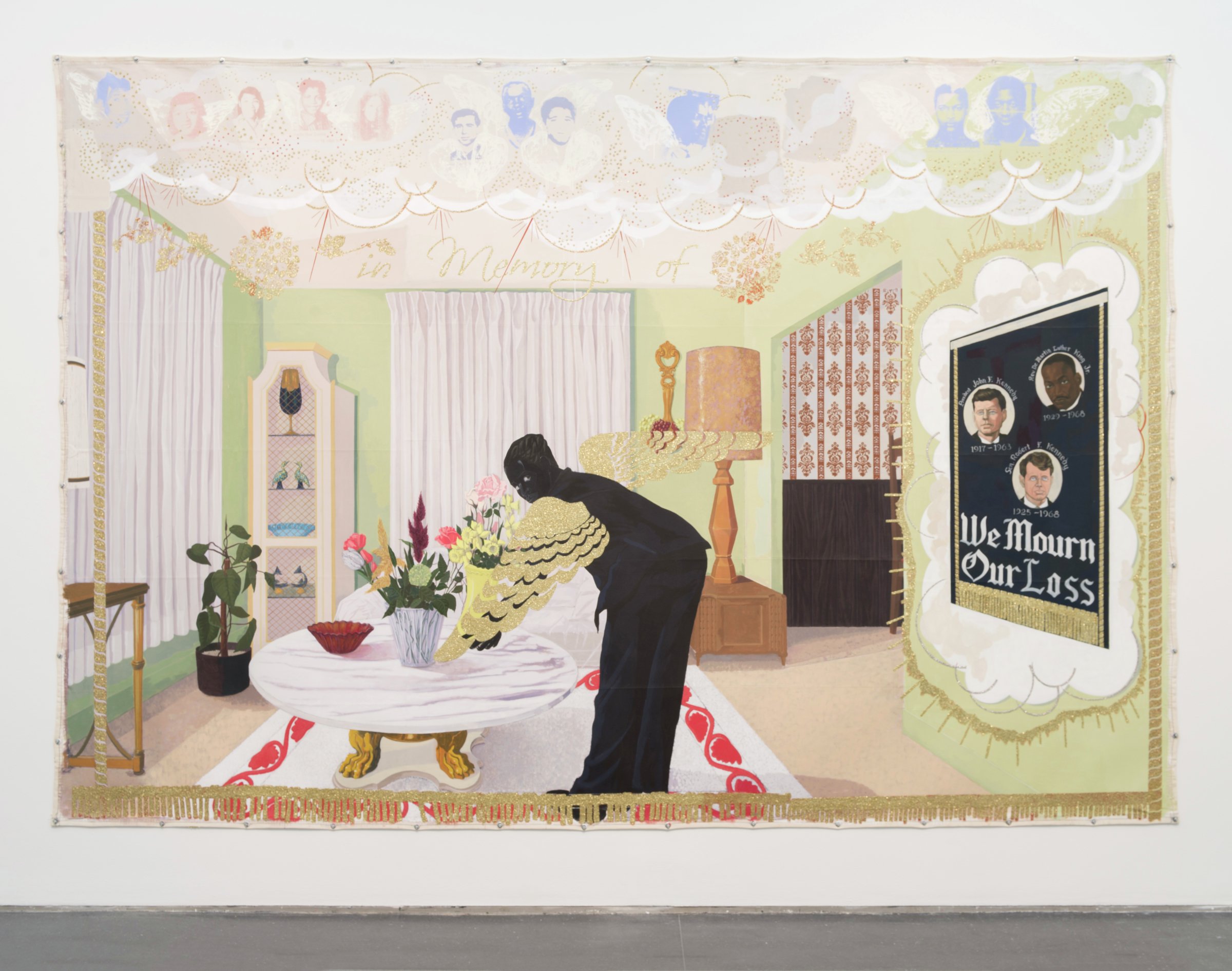

Some artworks fulfill the potential that the exhibition fails to execute more broadly, and the Loving Community section includes a number of them, such as Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir I (1997) and a series of mixed-media works by Tomashi Jackson, made from canvas, paper bags, and electoral yard signs, including some from Stacey Abrams’ 2018 campaign for Georgia governor. Depicting what appears to be a midcentury Black American domestic interior, Marshall’s Souvenir I is a rhapsodic, masterly painting: a lone Black figure looks back at the viewer, over golden-glitter wings, while arranging cut flowers on a tabletop; images of figures including Malcolm X and Fred Hampton appear to float, as if on clouds, above the scene. A banner hung on a wall memorializes John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy. On their own terms, these works contemplate democracy, history, and the fraught complexities of American identity as much as—or perhaps more than—they address love.

Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir I, 1997, acrylic, collage and glitter on unstretched canvas [courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and Bernice and Kenneth Newberger Fund]

As in the School of Love section, the sense of specificity articulated within the broader theme provides essential grounding for meaningful engagement with the exhibition’s claimed concerns. And yet, the success of these works raises more questions about the organization of Love overall: Why include so many artworks that offer no discernible contribution to the conversation that the exhibition is ostensibly pursuing? In a side gallery, no fewer than five paintings by German artist Magnus Plessen combine modes of expressionistic figuration and geometric abstraction in a series called Hoffnung, Liebe, Helium (Hope, Love, Helium) (2019–2020). Apart from one word in the series’ title, the five paintings, all individually untitled, appear entirely disconnected from the rest of the exhibition. Elsewhere, 24 canvases suspended from the ceiling and on gallery walls form an installation by Argentinian–Swiss artist Vivian Suter—but puzzling out what this work might have to do with love is left largely to the viewer, whom the wall text prompts to “contemplate the boundlessness of nature.”

Vivian Suter, Vivian Suter, installation view, 2019, twenty-four untitled and undated canvases [courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels]

Although a certain sense of capaciousness or buoyancy is often an asset to a thematically driven exhibition such as this one, here the central concept of love is deployed in such an open-ended, unspecified manner that it begins to lack cohesion or, ultimately, any real significance. Love becomes a cloak that obscures meaningful distinctions, rather than an illuminating construct for understanding the artworks on view or how they might relate to one another. The single quotation among the exhibition’s wall texts, from the late artist and poet Etel Adnan—love is “not to be described, it is to be lived”—itself feels like a misappropriated justification to not say anything conclusive on the subject. For a topic as universally written about as love, it is almost laughable that the voluminous wall text includes no other quotations from philosophers, poets, or even a love song, nor any citation of John Coltrane in the section called Love Supreme. It’s one thing (a regrettable one, sure, but forgivable) for a relatively vague concept to be instrumentalized by a curator for the purposes of exhibition-making, but it feels egregiously cynical when that concept is love.

Logan Lockner is a writer, editor, and critic based in Atlanta. He writes about contemporary art, film, and books for publications including 032c, Art in America, frieze, and GAYLETTER, and he hosts the radio show In Conclusion: A Review of Reviews on Montez Press Radio. He also contributed to the artist monograph Toyin Ojih Odutola: The UmuEze Amara Clan and the House of Obafemi (Rizzoli Electa, 2021). Previously, he was editor in chief of the Atlanta-based magazine Burnaway.