Wes Cochran

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS September/October 1990, Vol. 14, issue 5.

John Adams spoke for the founding fathers as well as for the young nation, when, speaking about French art he said that art and artists were “on the side of Despotism and superstition.” Adams, who felt that art was a threat to the new democratic liberties, that painting and sculpture were anti-democratic, went on to say that he “would not give a sixpence for a picture by Raphael or a statue of Phidias.” As the country grew and affluent Americans traveled abroad, they began to feel the need to establish some kind of cultural environment. A new breed of Americans developed who were willing to spend their sixpence for art. By 1805 a few small galleries began to open around the Art Academy in Philadelphia and in New York City. By 1842 the nation’s first art museum, the Wadsworth Atheneum, opened in Hartford, Connecticut. The general 19th century American public, however, still believed that art was a suspicious and European convention. The concept of the museum, at that time, implied not the visual arts but the natural sciences and soon every little urban center created its own “dime museum.” Here were the bottled freaks, the mammoth bones, and the wax figures of kings and queens, criminals and their victims, and other luminaries. These museums satisfied the national thirst for the grotesque and the bizarre.

In 1870, three major American fine arts museums, dedicated to education, moral uplift, and social betterment, were founded in Washington, D.C., Boston and New York. Consonant with the belief that art and education were inseparable, the man on the street was welcomed to enjoy these uplifting pleasures. This was a radical departure from the policies of institutions like The Louvre or the British Museum, whose holdings, primarily gifts from the monarchy and spoils of war, were accessible only to the artist, the scholar, the connoisseur, and the “gentleman.”

Art patrons began to emerge from the new American middle class. As American private collectors came very late on the scene, they cannot be compared with their European predecessors or counterparts. The Medici, the Walpoles, Catherine the Great, or the Pope were all in positions to have master works created for them and in tribute to them. Yet the American collector has more wealth and the freedom to exercise individual taste. Unlike European collectors of earlier times, Americans are not dictated to or bound by any particular tradition, cultural aesthetic, or standardized knowledge. Their tastes may be cultivated and exquisite or valueless and vulgar. The 19th century British value that social virtue and financial success are interrelated is still in practice in the United States today and will, seemingly, follow us into the next century. The making of art is often considered a lowly and insignificant profession, but the purchasing of the results of these labors of love is noteworthy and brings prestige to the buyer. The American economy is such that every generation has its own nouveau riche. Those who are made anxious by their new money and worry about their social acceptability and their public image have always tried to surround themselves with things beautiful and rare, original and expensive. Art attracts them.

There are always discussions and gossip about collectors and their motives whether they are trying to buy immortality, buying for investments, or trying to dictate taste. In a capitalist society it is difficult to understand how one might collect out of sheer joy and passion, or a desire to help preserve the culture.

Far away from the Metropolitan Museum and the international art auction houses is the Cochran Collection, 80 miles south of Atlanta, in LaGrange, Georgia. It is a typical Southern town with its central square surrounded by 19th century, red brick, two story buildings. Here and there are a few remaining antebellum mansions with six-over-six glass pane windows, their massive white Greek columns, archways, and all. Everything is clean, clipped, and kept. Near the square is the Chattahoochee Valley Art Association, an art museum; at LaGrange College is the Lamar Dodd Arts Center.

Surrounding the town is Southern farm country. There are no signs of the Industrial Revolution here, no abandoned smoke stacks, no rusting machinery, no millionaires or their generous endowments to build and maintain a museum. However, in an unpretentious post-WWII house is one of the finest collections of works on paper in the Southeast. Wes and Missy Cochran collect as a highly skilled and experienced team. They move about with the enthusiasm of “amateurs” who marvel with the excitement of seeing things for the first time. Collecting art and concern for the arts is their single passion.

Mildred Thompson: Coming from LaGrange, Georgia, can you tell us something about your early influences and introduction to the arts?

Wes Cochran: I guess every family has one member who is the wild card. In our family it was my uncle, William L. May. He had a tremendous art collection and after his retirement from the field of education he spent the rest of his life as an international art broker. He helped a lot of individuals and corporations get their art collections started. It was he who started us and inspired and guided us in the beginning with our collection. He told me exactly what to buy and I bought exactly as he said.

Thompson: Did he grow up in LaGrange? Did you grow up surrounded by this collection?

Cochran: No, not exactly. He was born in LaGrange in 1913 and after graduating from high school he left and never really came back. He traveled all over the place. After World War II he enrolled at Columbia University and graduated from there in 1952. He then took a position in Baton Rouge as Director of Spenser Business College. It was there that he and his wife Carol began collecting. Their collection had about 1200 works in it; it was called “500 Years of Printmaking” and went from the Renaissance to contemporary art work; it was one of the largest private collections in that part of the country. So my uncle’s knowledge of prints was very broad and very, very deep.

Thompson: Had you had any classes in art or art history?

Cochran: No, no, in the beginning I had no background in art. After I graduated from college in 1974, I went out to Colorado where my uncle was living in retirement, nine thousand feet up on the side of a cliff in Evergreen, Colorado. I lived with him and his wife for about six months over the winter. It was then that he became my friend and mentor and we formed a very close attachment. That was my very first exposure to his collection of prints.

Thompson: When and how did you begin to buy art?

Cochran: Well, in 1976, I was very fortunate in landing a job with a U.S. oil company as a roughneck, I did offshore drilling in the Persian Gulf for two years. I was young and single and out of debt, and I was making some money. Just about that time my uncle had come of retirement age and began getting more and more involved in the art world. In 1977, he wrote me and he asked me to send 1200 dollars and he would buy me a print. He knew I was making some money and he wanted me to invest it, instead of wasting it overseas. He was very protective and advised me to put my money into art. So I did exactly as he told me and purchased my first print

Thompson: And how old were you then? And what was that first work you bought?

Cochran: In 1977 I was 24 years old and the work was a print by Salvador Dali. I was eight thousand miles away but I continued to send him money to buy prints for me. By the time I got back to the United States I had accumulated about ten pieces of art. I trusted my uncle entirely because I knew that he had had thirty years of experience in choosing and buying.

Thompson: How did you respond to these ten pieces?

Cochran: They were at first shocking for me. My family in LaGrange was more shocked than me. They believed that William L. was wasting my hard-earned money. There was an Appel, a Calder, a Dali, Romare Bearden—they were all contemporary. They were all very colorful and they did appeal to me. I really didn’t know what I was looking at and I didn’t really understand but I felt that they were good and that we were really doing the right thing. I was under the direct influence of my uncle, and he was guiding me right by the hand. It was an innocent kind of thing in the beginning. I never dreamed it would blossom into what it is today. I really felt like putting money into art was better than putting it in the bank, or real estate.

Thompson: So you, at the beginning, were trying to make a “good” investment, as if you were dealing with stocks, bonds, commodities?

Cochran: Well, yes, in a way. He often told me that art was a tremendous investment, that it was not something to buy and sell overnight, that it would take 15 to 20 years to make a turn on my money. So my uncle used the idea of buying art as a “hedge against inflation” to convince me this was the best thing to do. He knew that I didn’t know anything, so I was easily convinced. And this is really how and why we began the collection.

Thompson: When did you begin to buy art on your own, make your own selections?

Cochran: After my uncle died in 1987. He bought the first piece for me in 1977. From then to ’87 I would never have attempted to buy anything without him. And by this time I was back in LaGrange and he was flying all over the world. I didn’t have or know the contacts. He would find things and call me from wherever he was, saying, “I have found a so and so—if you’d like to have it send me the money.” I did nothing but work and save to add to the collection. I was dislocated geographically, because I didn’t have the extra money to fly back and forth to New York. I lived very moderately and every dime I could imagine went toward art. There were no luxury items. By then I had really gotten the fever and I began to read more and more, trying to understand how the arts work.

My uncle advised building an art library as we built the collection. He also said that one can learn “from the hip pocket.” So the more I invested, the more I read. This, and the years I spent with my uncle helped us in later making our own decisions about selecting art for the collection.

Thompson: Looking back, how do you see yourself or evaluate this entrance into collecting?

Cochran: It’s amazing to look back and think of how ignorant I really was. I was however, very young, and it was beneficial to have started so young. I really believe that sometimes this thing called blissful ignorance is not so bad.

Thompson: If it’s guided in the right direction.

Cochran: That’s right, because it allowed me to indulge without any prejudices. I could be guided without hesitation. It was like having a manager. There was no one else in the country who could have known more about prints that he did.

Thompson: Was your uncle’s collection ever made available to the public?

Cochran: Yes, he would lend parts of it occasionally for exhibitions, usually at colleges and universities. I doubt if he ever got to see them all hanging anywhere at the same time, there were so many. When Nixon was in office, the Marlborough Gallery selected the collection to represent the US in a cultural exchange program. My uncle declined because he was afraid for its safety in crossing the war zones of Vietnam. The Chinese wanted it because it belonged to a commoner; they didn’t want a big well-to-do American to come blasting into China. So he was an ideal candidate.

Thompson: How many pieces have you now in your collection?

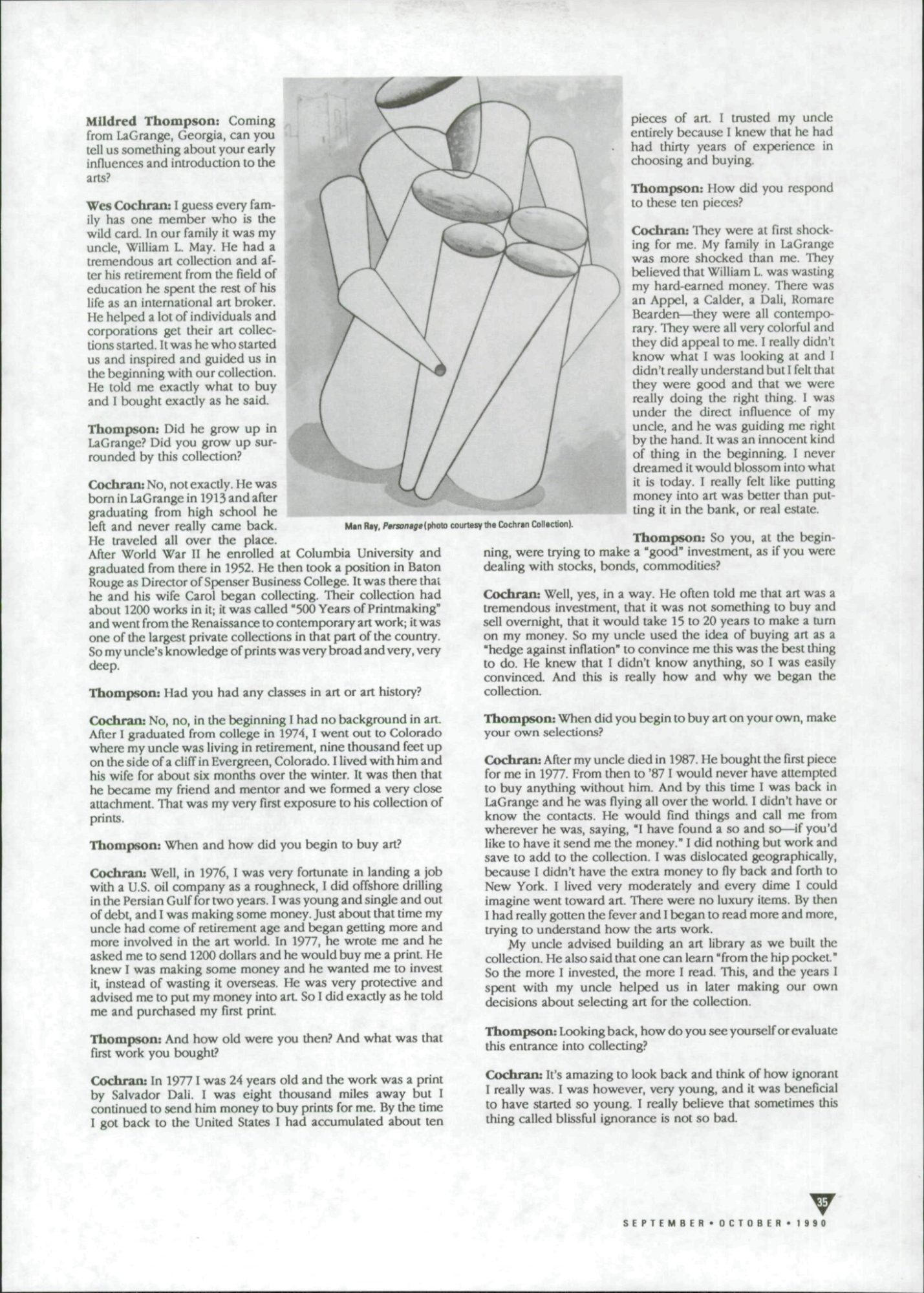

Cochran: About two hundred. They are all works on paper, mostly prints, but there are a few watercolors and a few drawings.

Thompson: Do you plan to continue to specialize in works on paper?

Cochran: Yes, they are what I feel most strongly about. I really enjoy the look, the feel, and the smell of prints. I hope we can go on collecting prints. Our collection emphasizes the past 50 years. Very contemporary, mostly American. We do have a few Europeans—Miro, Chagall, Dali, Picasso and some others.

Thompson: I have heard that you have quite a number of Warhol prints.

Cochran: In the beginning we saw that something was beginning to take shape, so we tried to develop it, to make some kind of statement about 20th century America. Soon we had about 54 pieces of Pop art—Warhol, Rauschenberg, Rosenquist, Johns. Of those 54 Pop pieces we decided to select one artist as a representative of American 20th century and felt that Warhol would do it best; we now have 20 prints by Warhol. He was the logical choice because I really liked his work and there was so much information available about him. And Warhol was a print artist and we were collecting prints. Also in 1980 when we started buying his work, it was really affordable. We are very happy to have these 20 pieces and would have continued to buy them but his unexpected death stopped us. When he was alive, his work was underpriced but now prices have escalated to where, it seems, I will never be able to buy another one.

Thompson: It is rumored that you are putting together a collection of works by African-American artists. Is this true?

Cochran: Yes, a couple of years ago. Missy and I went after this very aggressively—we always decide, and work, together. In 1988, I was able to meet Camille Billops, Howardena Pindell, Lois Mailou Jones and Faith Ringgold at the Atlanta College of Art when their work was in “Five Black Women.” I spoke to some of them about putting this collection together, and they were very receptive. Soon after that in New York we looked them up and were able to buy a number of their pieces. Now we have almost one hundred pieces. Camille Billops of the Billops-Hatch Collection has been a tremendous help to us. She is really the curator of this collection. Bob Blackburn has helped us a lot too. Perhaps 50% of the works were purchased out of his graphics studio on 17th Street.

Thompson: How do you go about making your selections? Do you have any specific criteria for the works or for the artist?

Cochran: Maybe we’re unorthodox, but we keep in mind that we want to share these things with the public. In the last five years we’ve taken the 20 Warhols and the 54 Pop works to museums in six southeastern states. We hope they’ve been educational.

Thompson: How are the arrangements made with the various museums?

Cochran: Working with the museums has been quite an education for us as well. It has allowed us to meet a lot of interesting people in the art world. We just let the museums know what works we have to offer, and we have made catalogs. We offer to rent the exhibitions for a very reasonable price. We are not trying to make a profit. The fees pay for the transportation—I rent a truck for delivery and pick up, and I drive it myself. Both Missy and I have jobs—she teaches in the public schools, I am a stonemason. This is for us a side line pleasure. The museums are always working on very limited budgets and most of them are in very small communities that would not always have access otherwise to anything of this nature. Also we are always warmly received in these small towns. For us too, it is interesting to see the work in different environments. The museum lighting and the open wall space puts us at a distance where we can really see them. We like taking them around.

Thompson: So the work arrives at the museums ready for hanging and with catalogues?

Cochran: Exactly, we do the framing and build the crates, deliver the works and place them around the walls. The museum people hang it and sixty days later we pick it up and move on to the next museum. So far we have stayed within in a radius of 500 miles of LaGrange; maybe in the future we can expand the tours.

Thompson: You have come a long, long way from your early beginnings. Do you now feel differently about what you are doing? Do you still consider the collection an investment?

Cochran: Today I think this has all evolved into something very personal. We have become much more mature and have formed a real appreciation for each of the pieces as well as for the general collection. Art is a very complex subject but we are beginning to feel more confident and comfortable with our choices. It requires for me, still, a lot of study and research. The investment thing is no longer so prominent as it was in the beginning.

Thompson: Have you sold anything from the collection?

Cochran: Well, we have really become attached to the work. We have never sold a piece. I don’t really think we could ever sell any of the pieces.

Thompson: How do you store the work?

Cochran: We live with it, we have it framed and it hangs everywhere in our home, and at my mother’s home. Sometimes we rotate it. It is always visible for us to enjoy. We learn a lot by seeing them everyday. It is true that the work really speaks to you.

Thompson: Do you think that your life and lifestyle is different than what it might have been because of your involvement in collecting art?

Cochran: Art means everything to us. It has added a whole new dimension to our lives by allowing us to be in contact with all these creative people.

Thompson: Have you made any plans for preserving the collection? Will you give it to a museum, or build a museum to house it?

Cochran: Missy and I have no children and expect not to have any children so one day we will have to make a decision. We would want to keep it together, but we have no definite plans as yet.

Thompson: Do people in LaGrange know that you have this tremendous collection of art? Do they accept you there? Is there a group with whom you can share your enthusiasm for prints?

Cochran: Well, I don’t know exactly how people see us. Everyone knows of us. It is sort of nice to come home and find a news clipping stuck in the mailbox, that someone has read about art somewhere and thinks we might be interested. They are looking out for us. I would like to be able to interact more but I don’t know of other collectors in the area, if so I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting them.

Thompson: What about the artists you meet?

Cochran: The artists we have met have been more than receptive. They are always friendly. We are often in New York and visit their studios and buy directly from them, without having to deal with galleries. The artists have been good about recommending other artists and all of this has been rewarding. We have tried to develop a reputation for being dependable, that our checks don’t bounce and that we keep our promises. We don’t take too much of their time, I hope, and so I think we are seen as serious and sincere. From what I have seen of the artists in their studios, they are very hard working and energetic. They are pretty much established as far as their work is concerned. They have all been formally well trained and involved in art all their lives. They are struggling, I’m sure, in trying to just make ends meet, but they are still very serious about their work. These are not emerging artists. When we buy we are looking for those who have been around for a while, the mid-career group.

Thompson: Do you prefer any particular style?

Cochran: Oh no, we are looking for a work that best represents that particular artist. It can be any style. We think of how it will fit into the collection when the collection is seen together as a whole.

Thompson: Now that you are solely on you own, do you find that you are developing a personal taste in any way? Have you considered collecting other mediums?

Cochran: Yes, I feel a lot more confident. We are beginning to trust what we like. We like the prints and will continue to buy them. Sometimes I think it might be interesting to collect photography. Oil paintings are still out of our price range, but we have begun to study them.

Thompson: What are your next exhibition plans?

Cochran: Right now we are at the Lamar Dodd Art Center in LaGrange with our Cochran Collection of 54 pieces. Our Warhol Collection is at the University of Georgia Museum in Athens and we are about to open in Columbia, South Carolina. These are booked through 1994. Our African-American Collection will open in the Spring of 1991 and it is already booked through 1992. We are now putting together the African-American Collection’s catalogue. Dr. Richard Long has written a brilliant introduction for it and we are waiting for articles from other African-American scholars as well. The works are being framed and crates are being built. Now we are getting ready and we are very excited about these new additions and new presentation of the Wes and Missy Cochran Collection.