We’re in for Better Wetter

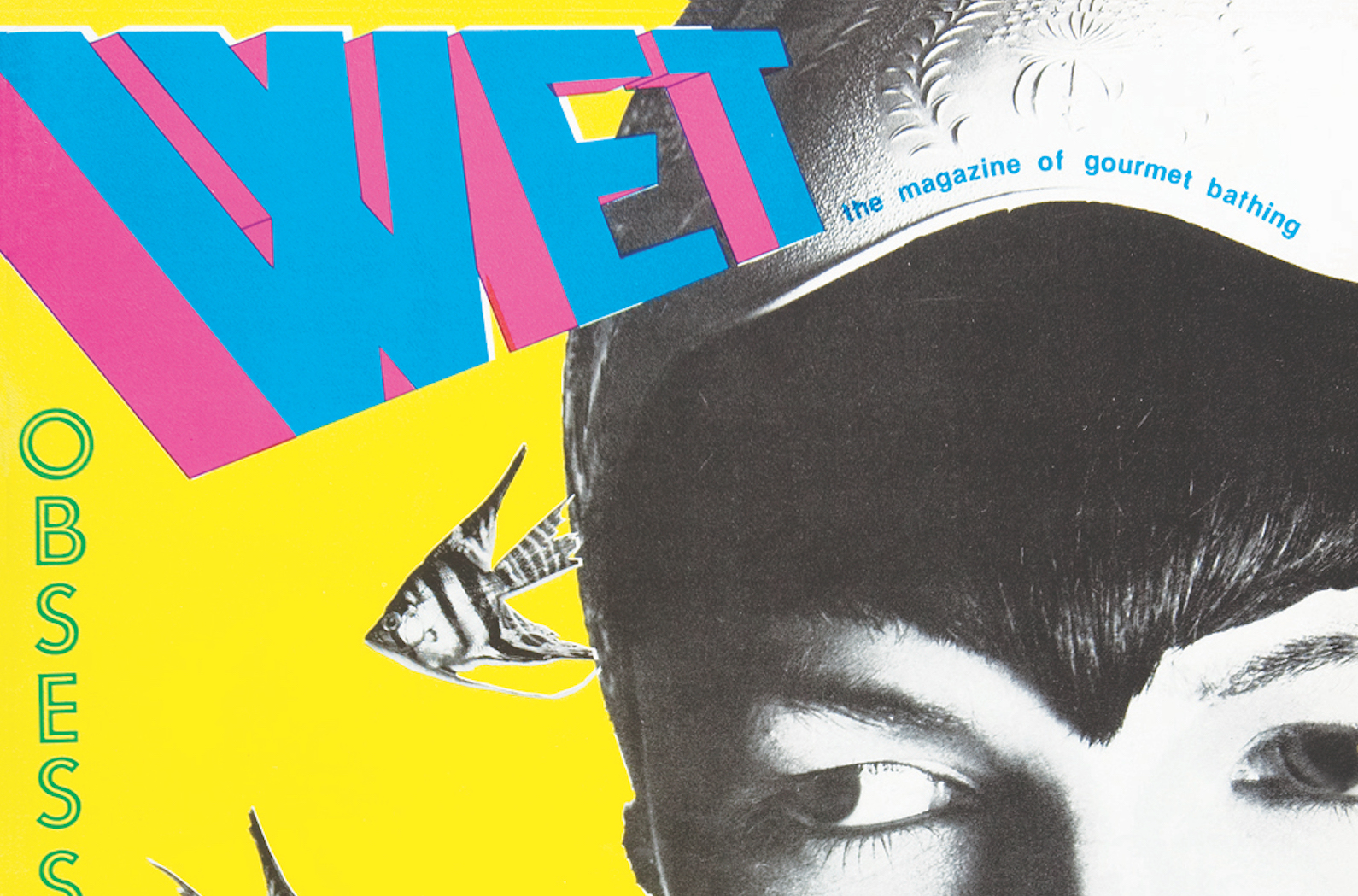

Obsession cover, Jul/Aug 1978 [courtesy of WET]

Four decades after the publication of the first issue of WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing, the premise seems almost impossible. Los Angeles is bone dry. Five years into a drought, the very thought of water, steam, mud, sprinklers, or pools is decadent. El Niño, a fever dream for Californians — a lover who teases, but never delivers.

Share:

And, at a time when the Internet is an endless well of sexual imagery and oversharing, it’s hard to fathom the idea that nakedness could be liberating, avant-garde, absurd, or playful—all guiding tenets of WET. This ethos is exactly why the magazine, founded by writer, editor, and artist Leonard Koren in 1976, is still relevant. Wetness undermines assumptions and upsets conventional understandings; bathing suggests that, even in a media-saturated environment, intimacy is possible, in both private and public spheres.

Koren, who received a master’s degree in architecture and urban planning from UCLA, led WET‘s team of writers, editors, artists, and designers for what he describes as a “spirited five-and-a-half-year assault on good taste and linear thinking.” By the time the magazine folded in 1981, it had made a mark on LA’s cultural landscape—or perhaps it had seeped into the city’s groundwater to become a pervasive part of how we understand the informal undercurrents of the city.

Mimi Zeiger: Let’s set the context for WET. What was going on in Los Angeles and Venice [Beach] in the late 1970s that made a magazine about “gourmet bathing” seem like a good idea?

Leonard Koren: Los Angeles didn’t seem very culturally cohesive—at least that’s the way I remember it. There were distinct neighborhoods—Westwood, West Hollywood, Culver City, Echo Park, et cetera—separated by vast nondescript zones. Venice was still a forgotten slum by the sea. Yet it abutted the Pacific Ocean, and rents were relatively cheap. So many artists and other creative types had studios there. I lived in what was once a gondola garage. A few of my neighbors had created amazing bathing environments in their living and studio spaces. That inspired me to explore bathing as a subject for art, which eventually led to making a magazine about gourmet bathing.

Mimi: You lived in a gondola garage? What is that exactly? Do you mean like from the Venice canals?

Leonard: Yes, I lived in what was formerly a gondola garage—a place where gondolas were stored and repaired. As you probably know, when Venice was developed as a seaside resort in the early twentieth century, a network of canals was dug out of what was then swampland. When most of the canals were later filled in and paved over, the gondola garage was converted into an automotive repair shop. At some point the automotive repair business folded, and the building was purchased by artists who divided it into four live-work spaces. I lived in one of those spaces.

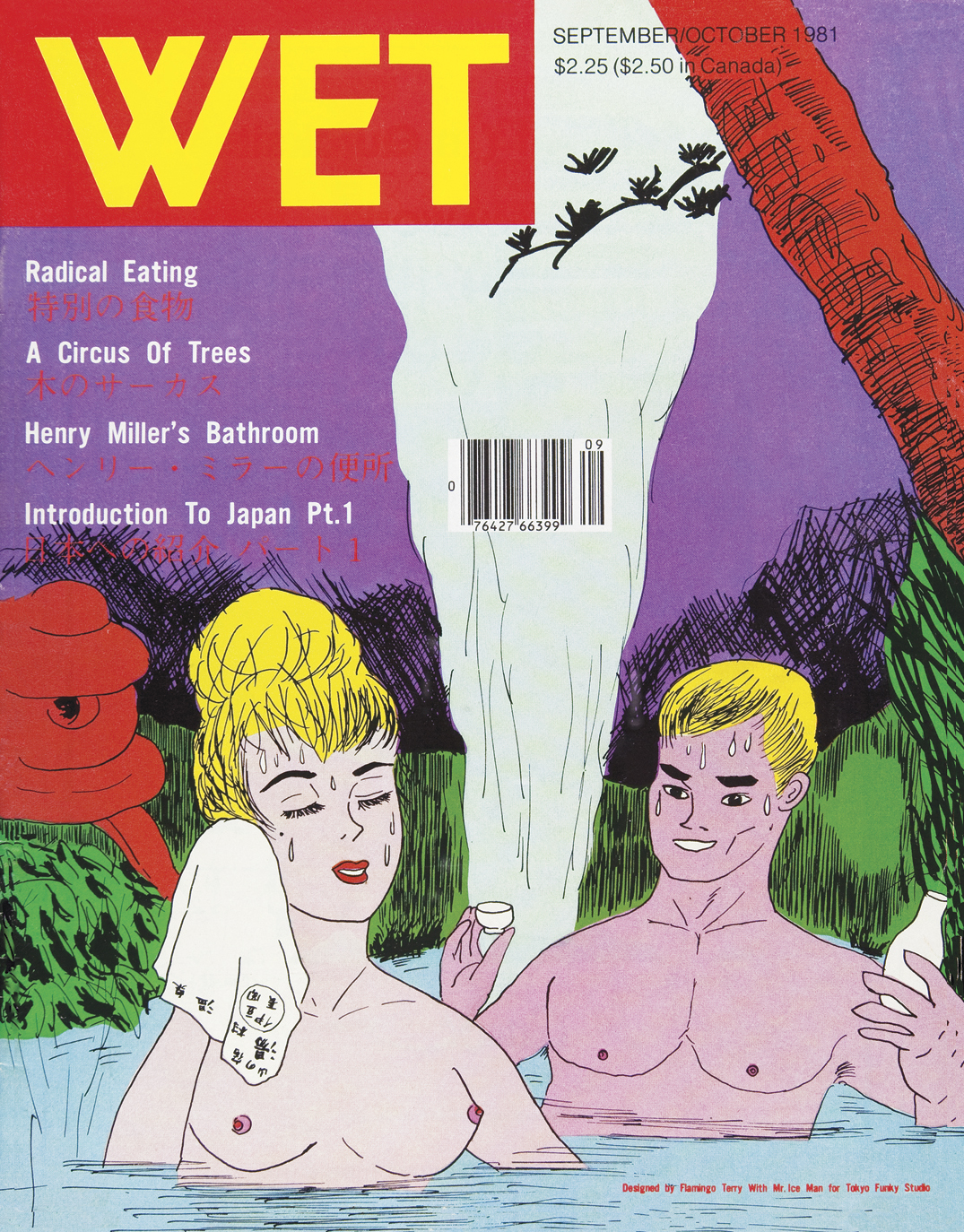

Japan cover, Sept/Oct 1981 [courtesy of WET]

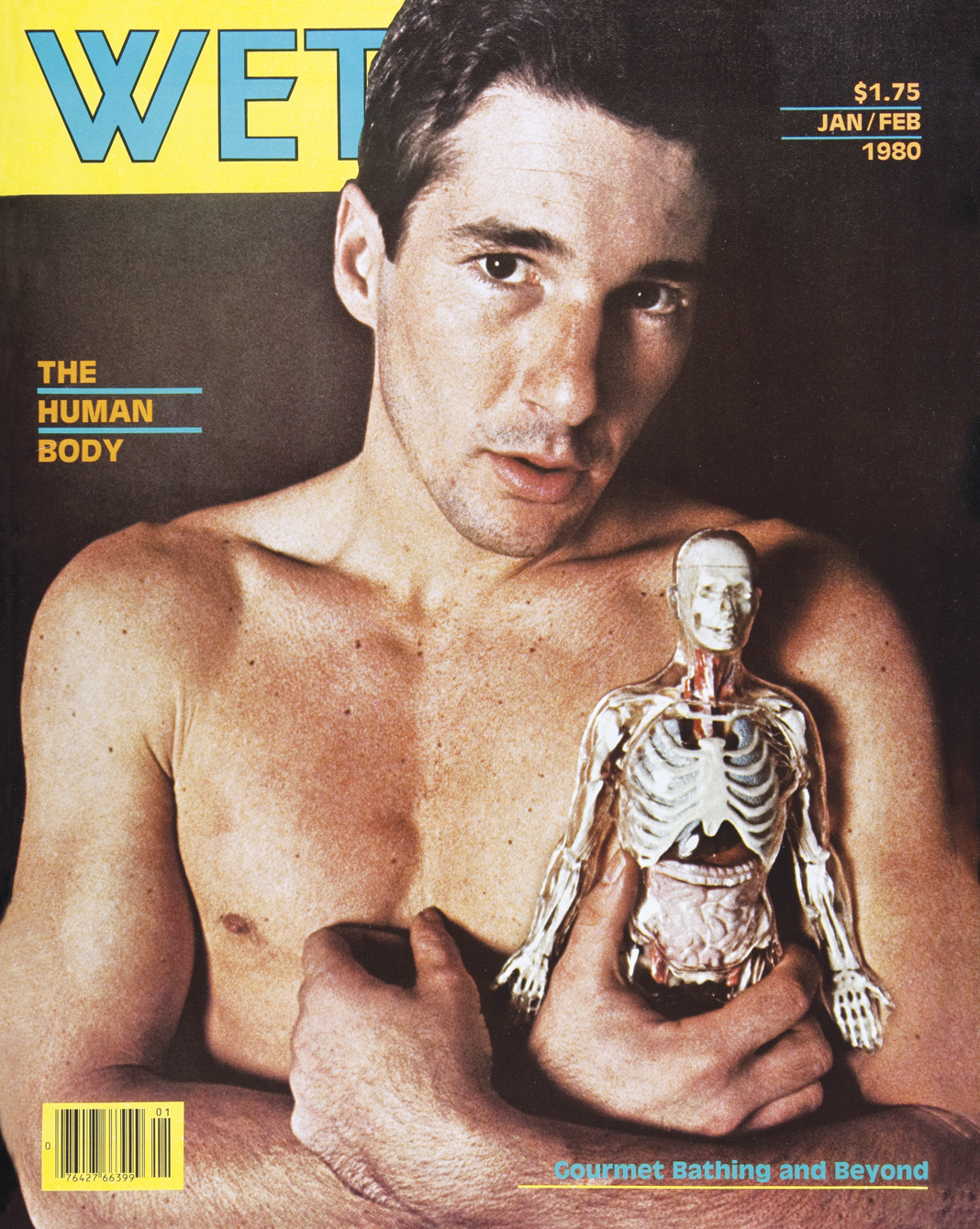

The Human Body cover, Jan/Feb 1980 [courtesy of WET]

Mimi: Could WET have developed anywhere … other than LA at that time?

Leonard: Perhaps in New York, but New Yorkers seemed to take themselves a bit too seriously. LA was probably perfect. LA was mythologized as being laid back. Gourmet bathing fit nicely into that mythology. In reality there was a multitude of ambitious, angst-driven writers, photographers, graphic designers, illustrators, and other creative talents hungry to make it in world of publishing. This was the fuel that powered WET.

Mimi: Was it meant to be transgressive? Or did it simply come out of what was brewing in art and design at the time?

Leonard: WET questioned many of the cultural taboos of its time, but there was no effort to be gratuitously transgressive. The magazine’s approach was light, playful, ironic. Editorial subjects that glorified cruelty or mocked human dignity were assiduously avoided.

Mimi: Why “gourmet”? And tell me more about this amazing equation you developed between humor, sex, and water.

Leonard: The term “gourmet bathing” came as an epiphany while taking a bath—really. I liked the semantic frisson of the two seemingly incongruous words. I thought I could have fun developing a magazine around this ambiguous concept. As for the humor, sex, and water, that was largely a reaction to my life in LA. I was 29 years old when I started WET. Like many of my peers I was attuned to sex and sensuality. And humor? It seemed like a good response to the absurdity of human existence.

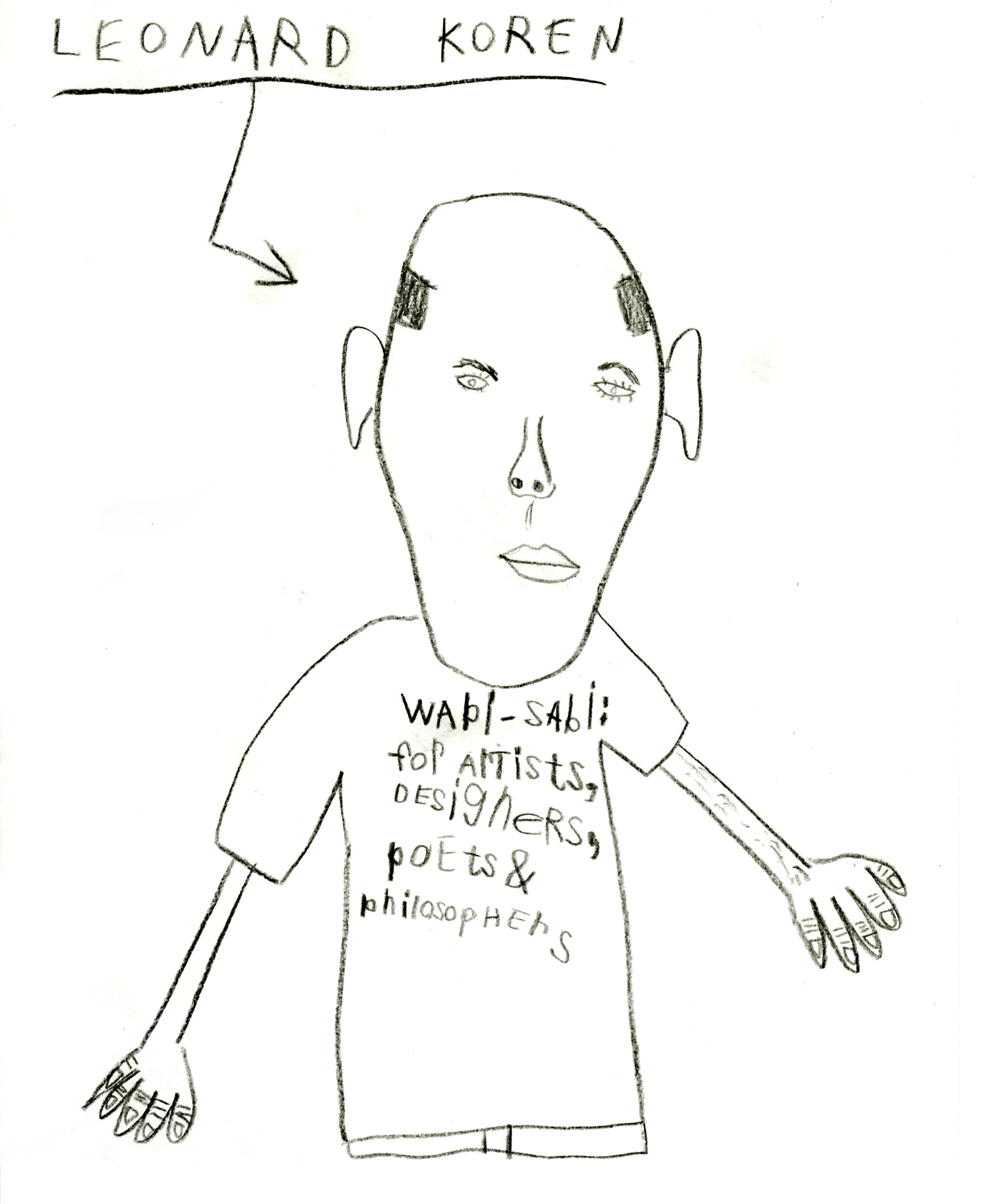

Marco Korena, Portrait of Leonard Koren [courtesy of the artist]

When interesting new ideas are absorbed into the culture they no longer seem either new or interesting.

Mimi: Whom did you ask to bathe? You wrote in your 2012 book Making WET that you’d give people instructions to bathe by. Were these scores? What makes good bath time?

Leonard: The models for my bath-art projects were friends and acquaintances—mainly artists and other creative types. I didn’t actually give exact instructions on how to bathe. But I found or made bathing environments that inspired particular ways to bathe. My purpose was to photograph those bathing, and then configure the photographs into more complex graphic images.

Mimi: Can you give a particular example of a bathing environment that inspired particular ways to bathe?

Leonard: One of my bath-art pieces was shot in a functioning stall shower in the middle of a typical dingbat apartment living room in Hollywood. The apartment belonged to Paul Ruscha, brother of Ed. Paul let me invite 18 men—including himself—to shower amidst a sofa, a lamp, an armchair, a coffee table, stacks of magazines and newspapers. In another instance, I transported a funky cast-iron tub to an opulent Brentwood back yard, and then filled it with warm mud. Friends and acquaintances came every hour on the hour throughout the day to immerse themselves. In both cases, the incongruities of the setting affected the way people bathed.

Mimi: Do you see parallels between the collaborative act of making a magazine and the communal bathing?

Leonard: I can invent some specious parallels, but there really were none. They both just happened to be gratifying—but unrelated—activities that occurred in temporal proximity when making WET.

Mimi: In the pages of the magazine you collaborated with so many artists and designers who would go on to do amazing work: April Greiman (who is designing this issue of ART PAPERS), Matt Groening, Herb Ritts. What does collaboration mean to you? Do you still collaborate?

Leonard: Making a magazine is really all about collaboration. When young photographers, graphic designers, illustrators, cartoonists, et cetera came to the WET office, I tried to determine what their unique talents were. If I thought they had something to offer the magazine, I figured out tasks for them. Some seemed to need a lot of explicit direction—so that’s what I gave them. Some needed very little—so I backed off. Contributors weren’t paid in actual money. The quid pro quo was great creative work in exchange for exposure in what was then a very hot publication. … Nowadays I make books that, for the most part, require very little collaboration. Copy editing and book production, that’s pretty much it.

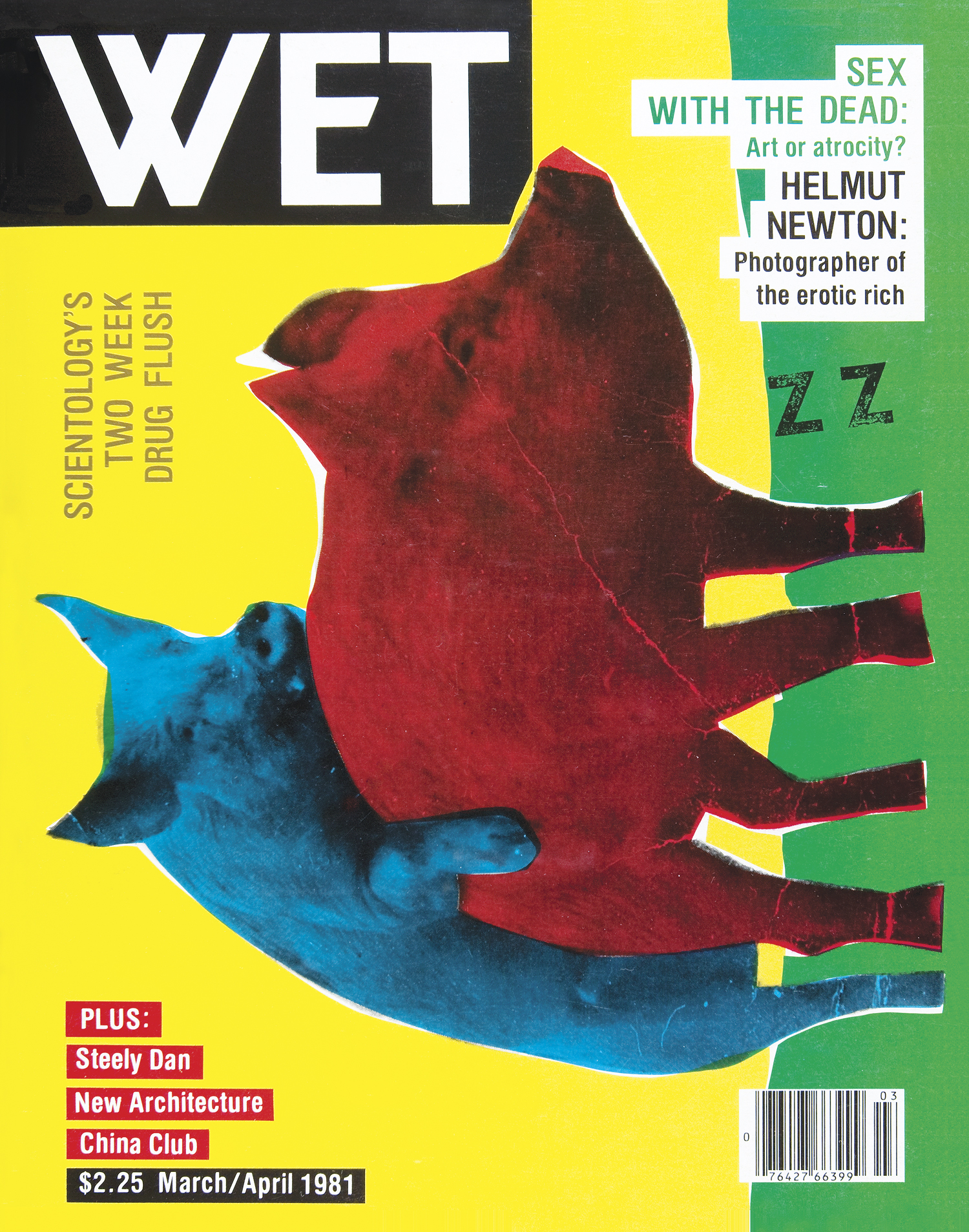

WET: ZZ cover, March/April 1981 [courtesy of WET]

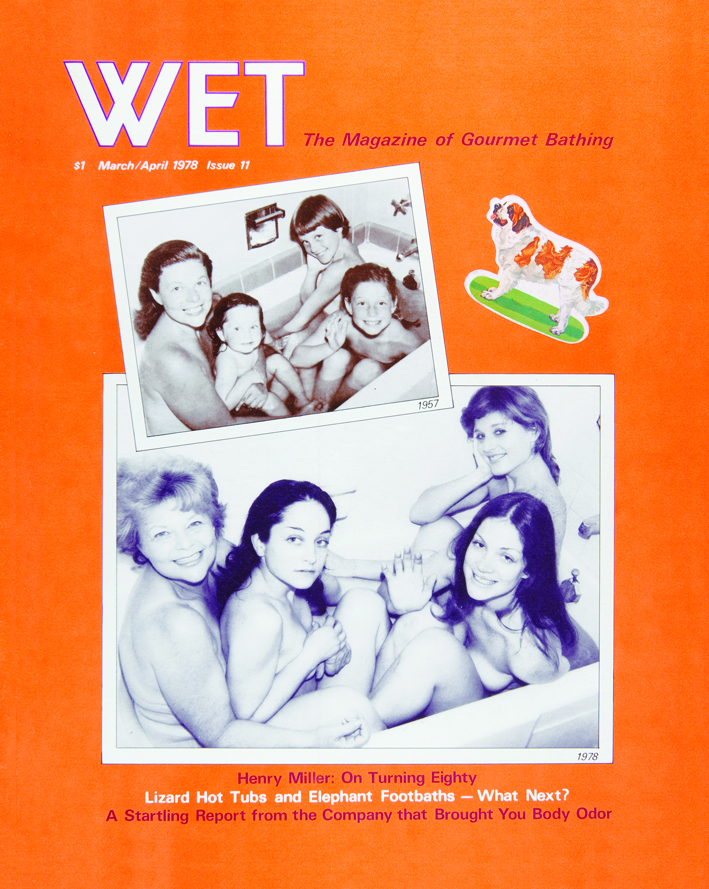

WET: Issue 11 cover, March/April 1978 [courtesy of WET]

Mimi: Looking back on WET, what lessons does it offer us now? What could LA relearn from its pages?

Leonard: When interesting new ideas are absorbed into the culture they no longer seem either new or interesting. I think that’s largely what happened with what WET had to offer. But I haven’t lived in Los Angeles since 1982, so I’m not really qualified to comment further.

Mimi: California is facing another year of drought; do you have an opinion on “dry,” the opposite of wet?

Leonard: I like the hammam, the architectural descendant of the Roman bath. It’s a great way to bathe using almost no water. I can see hammams in our future!

Mimi: I love the idea that the hammam could help with the drought and that we would start bathing more communally. They are also such beautiful structures. Do you have a favorite?

Leonard: My first experience in a hammam was in Paris in the early 1970s. I believe it was part of a complex called the Mosquée de Paris. It may still exist. I found the atmosphere very intriguing. The most beautiful hammams I’ve seen subsequently were in Turkey, but I don’t remember the names. They were mostly located in small- to medium-sized towns in the western and central parts of the country. Places like Bursa, Beysehir, Cekirge, and Sille.

Mimi: This issue of ART PAPERS is themed around “pool.” What do swimming pools mean within the constellation of wetness? As opposed to showers or tubs?

Leonard: Pools seem to represent the public face of bathing. That is, they’re about exteriority— appearance, style, and fashion. When the word “swimming” is added, physical fitness becomes part of the picture. And then bodies on display. Then bathing suits and accessories …. At the other end of [the] bathing spectrum, there is the intimacy of tubs and showers. It’s more about the visceral experience, how you feel inside as opposed to an image you project for others to see. As far as I’m concerned, the apotheosis of bathing in a tub is doing absolutely nothing. Being still, quiet … disappearing.