What Cannot Be Held—Malcolm Peacock’s We Served … and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon

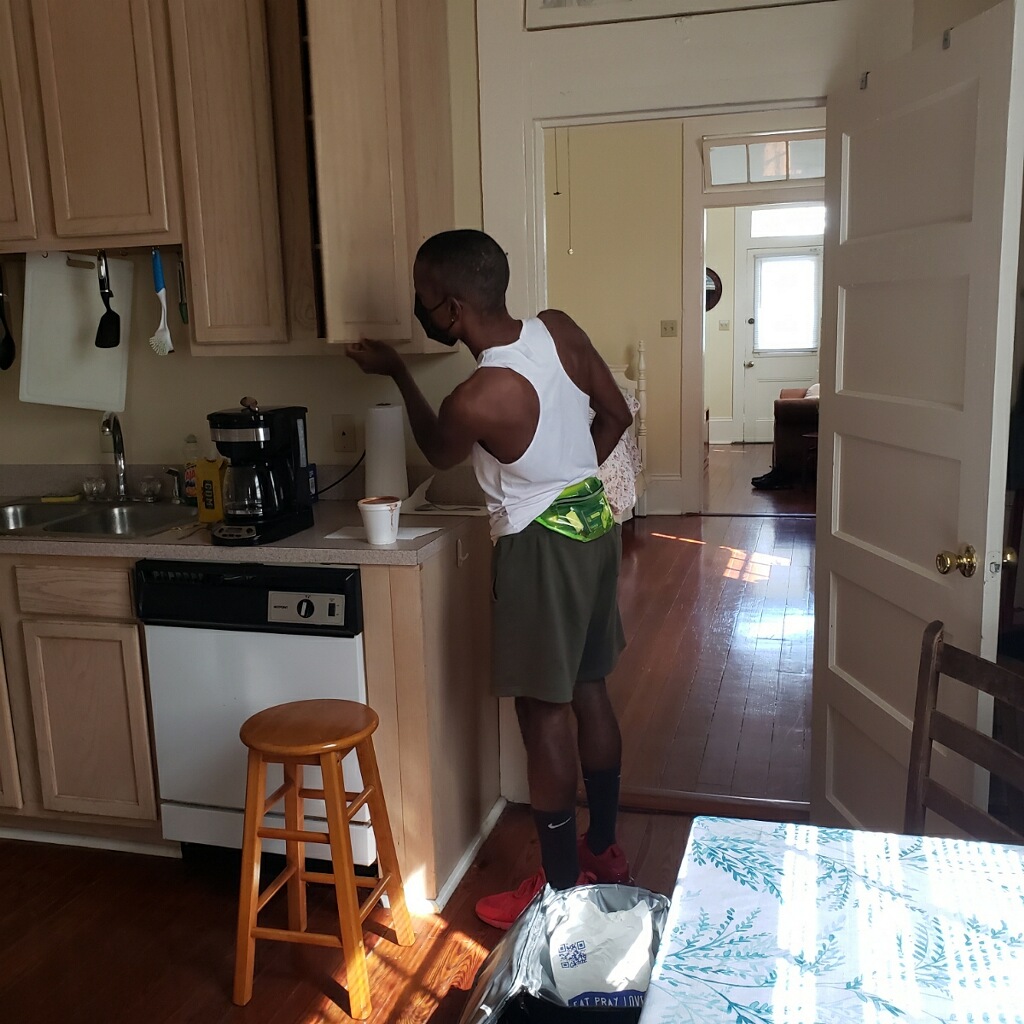

Malcolm Peacock, We Served…and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon, 2021 [photo: Klaus Biesenbach; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

In a shotgun house in the Irish Channel neighborhood of New Orleans, I anxiously waited for 2 pm. I had secured a much-coveted timeslot to experience We Served … and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon, a performance by multidisciplinary artist Malcolm Peacock. It was one of few premiering events at the initial opening of Prospect.5: Yesterday we said tomorrow. This fifth iteration of the city-wide art triennial was staggered in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the after-effects of Hurricane Ida, with major Prospect venue openings occurring in October, November, and January. As the city, various cultural institutions, and individual artists return to relative stability, Prospect.5 attempts to maintain one of its founding missions: to stimulate the economy of New Orleans. Peacock was one of an intergenerational group of 51 participants tasked with offering thoughtful and responsive work in a time of global uncertainty. We Served … involved Peacock traveling to a private location of my choosing. The instructions for the experience were simple. I would be served a meal “built” for one—that is, an experience for me, and only me.

Malcolm Peacock and I share beloved friends and several colleagues. He has my personal cell phone number and has been a guest in my home. Although we have maintained a friendship for some time, I had yet to experience his work. I knew that his practice is expansive, consisting of site-specific performances predicated on human interaction and willing vulnerability. I Guess I’m Stuck With Me (2019) involved audiences walking in close pairs throughout a neighborhood in Baltimore while each listened to one of two audio tracks. Often pairs of strangers were invited to reconceptualize the spaces around them through the frequently contradicting narrations of two lovers. All Kinds of Things (2018) involved the artist reading excerpts from The Autobiography of Malcolm X to intimate audiences in a garden space in upstate New York. Each performance involved an interrogation of history, space, and memory, implicating Peacock’s participatory audience in a unique experience that is not easily documented.

Being Black, queer, and male-bodied, and having been raised working class, my experience of We Served … depended on how I understand myself in relation to power. As is the custom of Black folk, I assumed that there would be mutual niceties exchanged between us. Although the house where we met was not my home, I had brewed a fresh pot of coffee, had fruit on the table, and prepared to embrace my friend as he came to share with me a meal of red beans and rice. The little house had no front porch, no liminal space for gentle transitions. And so there were no greetings, no embraces. Peacock entered and proceeded to walk from room to room, confirming that we were alone. He then settled directly into the kitchen and began setting the table for what I assumed would be our meal. After my few failed attempts to initiate conversation, his silence forced me into my role. It was not our meal. It was my meal. He was there only to serve. The performance had already begun.

Malcolm Peacock, We Served…and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon, 2021 [photo: TK Smith; courtesy of the artist]

Peacock’s slim body moved as if not to be seen or heard. Swiftly and silently, but boldly, he rummaged through cabinets and drawers as if this were his own home. After placing one bowl, one napkin, and one glass of water on the table, he then pulled out a chair and stood waiting. I thought to myself, Ah, I know this game. I’ll play mas, the satirical performance of power. I took my seat and smiled at him, thinking, Yes, we both know this game, maybe we’ll take turns and later I’ll let you ride on my back and play horsey. After filling the small porcelain bowl with the pre-prepared red beans and rice, he retrieved a small speaker from his bag, placed it on the table, and pressed play. The sound of his running feet hitting the ground filled the room and offered me some comfort from the previous silence. Through the speaker, his labored voice uttered a “good morning” as he ran. My sudden relief at this verbal acknowledgment further emphasized his refusal of etiquette. Positioning himself across the kitchen table, Peacock stood, bent at the back, and prostrated before me. He dug the spoon into the New Orleans delicacy and tapped it on the edge of the bowl. He then lifted the utensil, making eye contact for the first time. The audio continued, “I want to provide context this morning for what I wish to discuss, on the topic of touch … ” He extended his hand toward my face, carrying a spoonful, and waited. I opened my mouth, and for the remainder of the hour, he fed me.

We Served … incorporates elements of endurance and confessional narrative to comment on the precarious relationship between touch and power. Being fed is a seemingly loving act that, for me, inspired thoughts of my mother. In my most vulnerable physical state, she fed and protected me—an act of love that I will one day return. Two queer Black men, one feeding the other, is seemingly loving. It brought to my mind the recent history of communal care in the face of the persisting AIDS epidemic—an experience many more are learning, intimately, as they care for their loved ones with Covid-19. This performed feeding made the feeling of being Peacock’s friend—the nourishment of intellectual fraternity and mutual respect—into a physical act. Steadily he assuaged my hunger, feeding me spoonful after spoonful, while making direct eye contact that appeared apathetic to my returned gaze. He wore a mask, above which his auburn eyes were unwavering. I often found myself lost in their emotive power, a silent communication between players in a scripted game. I mused over the erotic. Was his intent that I feel the pleasure of holding power over him, to be fed? Or did he hold power over me—because he rejected my niceties, because he asserted his subservience—as the administrator of my pleasure?

A critical point in the performance came when Peacock held the spoon in my mouth just a few seconds longer than before. He held the spoon firmly, all the while maintaining eye contact, fully exposing my vulnerability. This action suddenly prompted me to question the integrity of his touch. I felt in that moment overfed and, with red beans and rice spilled down my shirt, as if I were mocking infirmity. We Served … made clear the intimate and intricate exchanges of power between the server and the served, the oppressor and the oppressed. In direct reference to the work of American scholar Hortense Spillers, Peacock offers his “touch” as proof of alienation from a body that has been invaded, coerced, and penetrated—our Black, queer, and beautiful bodies. Histories of enslavement, servitude, and patriarchy in the United States provided context for Peacock’s enduring bent back, his dutiful silence, and my own willing complacency. The performance eloquently implicates the nation, the city of New Orleans, and Prospect.5 itself in an immersive personal history. Our game was an allegory for the benevolent “feeding” of those we know to be weaker and more vulnerable than ourselves. The backhand of performative generosity is the public acknowledgement of much larger and older systemic inequities. These evils appear in the distribution of resources, in the design of a city, and on the tip line of a receipt. I shudder to imagine the race, class, and gender play between Peacock and the more than 50 people with whom he performed the work over the course of Prospect, many of those with identities not like his own. You cannot play mas with master.

Malcolm Peacock, We Served…and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon, 2021 [photo: TK Smith; courtesy of the artist]

We Served … was performed repeatedly over the duration of Prospect.5 in public parks, hotel rooms, and at kitchen tables across the city of New Orleans. Encapsulating the overall tone of Yesterday we said tomorrow, the performance made visible the chronic wounds caused by persisting systemic inequities, and these were made more visceral by Peacock’s exquisite manipulation of intimate social behavior. In an effort requiring an inconceivable amount of physical and emotional labor, Peacock held this mirror up for participants, enabling them to see the power they wield and reckon with their relation to the greater dynamics of the present moment. The recorded audio asked, “How do we describe experiences of the flesh, experiences that shouldn’t happen to anybody?” Our game of volleying power offered a guttural response: You make them feel it. After so much had been said about loving and violence, abuse and autonomy, the audio ends in sobbing. Across the table, Peacock’s eyes welled with tears. Suppressing the urge to hold my friend, I continued to play my part, not stopping the performance, or pausing the audio. He played his part, not moving from his servile posture, allowing me to witness his exhaustion from feeding me something I could not hold in my hands or in my stomach.

TK Smith (he/him) is a Philadelphia-based curator, writer, and cultural historian. His writing has been published in Art in America, the Monument Lab Bulletin, and ART PAPERS, where he is a contributing editor.