We Say What Black This Is

Share:

Amanda Williams observes the square, abstracted concepts of blackness, and the prevalence of race in cyberspace. Instagram is a landscape riddled with subcultures, digital aesthetics, and identity constructions. For We Say What Black This Is (February 7–May 24, 2025), the Spelman College Museum of Art’s Curator in Residence Karen Comer Lowe—scavenged for each work in the exhibition. Pulling from public and private collections, Williams’ What Black Is This, You Say? series is now under one roof. All the included works were created in response to the 2020 police killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor—deaths that, once surveilled and circulated online, fueled a wave of “digital activism” trends.

Among the most notable of them was the Black Square movement, a widespread yet shallow gesture meant to signal solidarity. What began as a feeble act of performative allyship quickly devolved into a sea of black squares filling social media feeds—flattening hashtags related to Blackness into a one-dimensional concept and color. In 2020, Williams responded by posting hundreds of her own black squares, each illuminated by splotches of light and color. Her adaptation was a direct challenge to the perfunctory trend, concentrating on bringing forth layered identities, histories, and lived experiences of Black people across different backgrounds. Departing from social media, she kept the square and switched to watercolors and oils.

Amanda Williams, What black is this you say?—”A west side imma snatch-yo-edges-back-with-a-hand-gesture black—black (08.27.2020), v2, 2023, Oil, mixed media on wood panel, 60 x 60 in.

[Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York] Photo: Jason Wyche

Amanda Williams, What black is this you say?—”You once told me you wanted to live somewhere where there are more than 4 or 5 ways to be black”—black, 2021 Oil, mixed media on wood panel, 60 x 60 in. Collection of the Blanchard Nesbitt Family. [Image courtesy of the artist, Rhona Hoffman Gallery and Casey Kaplan, New York]

Amanda Williams, What black is this you say?—“You secretly believe praying over your smothered pork chops reduces the risk of hypertension and calories”— black, (study 06.06.20), 2020, Oil, mixed media on wood panel, 20 x 20 in., Collection of Mark J. Bevington. [Image courtesy of the artist, Rhona Hoffman Gallery and Casey Kaplan, New York]

The aptly named We Say What Black This Is at Spelman includes poignant reflections, written by art history students, for each of Williams’ works. Presented as extended wall labels, they serve as an elucidation of Williams’ question-and-answer-style titles. The exhibition is thus supported by these students from a class on Williams’ work taught by the museum’s curator-in-residence, Karen Comer Lowe, and director of the Atlanta University Center Art History and Curatorial Studies Collective, Cheryl Finley. Williams participated in the AUC Art Collective art history department‘s distinguished lecture series and led a workshop with the students, which resulted in a dedicated course during the spring 2024 semester that focused on Williams’ practice. Williams, who was directly involved with the course, virtually attended class critiques of the students’ didactic label drafts.

Karen Comer Lowe (left) and Spelman College President Rosalind Brewer (right) at the “We Say What Black This is” opening reception at Spelman College Museum of Fine Art. Photo By by Julie Yarborough

After entering the museum, I was greeted by a smiling Spelmanite and the mahogany hardwood floors there that always feel like a warm welcome. I was excited to see, up close, how Williams investigates these ideas—and how the students would unpack her work. In an intimate black box gallery featuring three paintings—which range in size, on canvas, wood panel, and paper—each work is saturated with deep and dark reds intended to signify Kool-Aid. Each work is titled What black is this you say?—“I thought red koolaid was juice til I was 10 years old”—black (06.03.20). A speaker plays a text recited by Spelman Alumna, Ming Washington. Washington’s voice comes softly from the speaker, describing Kool-Aid in a nostalgic and playful way, reflecting on the experience of drinking Kool-Aid, focusing on the sensory details and cultural significance of enjoyment without concern.

Amanda Williams, What black is this you say?—”El Español es tu lengua materna pero estás orgullosa de tus raíces Africanas.”—black (08.05.20) v2, 2022, Oil, mixed media on wood panel, 60 x 60 in., Collection of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art

Here, the didactic label is a poem. Hearing the words “a lip stain, a tongue tattoo, a marker that your favorite flavor is red or blue, grape, orange, lemon lime, or watermelon” evokes a shared experience of Black juvenescence. Kool-Aid isn’t freshly squeezed from fruits; it comes from packets of sugary flavored drink mix that needs only water added. As a kid, you couldn’t tell the difference. But this affordable and tasty drink has been associated with poverty, as it was cheaper than soda and other mainstream beverages, which led to Kool-Aid becoming socially intertwined with the Black community.

As a throughline in her practice, Williams explores color as a racial signifier and as a chroma that has the power to create a shared kinship to those who had similar upbringings or experiences. Williams, in using the title What black is this you say?—“I thought red koolaid was juice til I was 10 years old”—black, is asking, “What do you know about this?” Everything between the em dashes tells you what aspect of Black life is being put under a microscope.

A grid of 21 miniature study paintings offer a chance to observe Williams’ layered process of placing color and how she works through her larger paintings. The grid works bear pencil-scribbled words and lines that point to certain parts of the square, as Williams works out metaphors and identifies the pressure points in the way color interacts. By soaking each square with watercolor, overlapping and melting together, her brushstrokes create layered translucent washes. Here, we see that in her practice, she starts small, with watercolors, then moves to 20 x 20–inch, and, eventually, to much larger works, such as the 60 x 60–inch canvases in the exhibition. You can see the progression of an idea through the increasing scales, and it’s fascinating to watch her ideas grow. The subtlety and complexity in the details are easier to spot in the bigger works, where you can see the movement and more intricate elements. It all lays softly like clouds of color.

Opening Reception Images of students from the AUC Art Collective by Julie Yarborough for Spelman College Museum of Fine Art

In What black Is this you say?—“ You once told me you wanted to live somewhere where there are more than 4 or 5 ways to be black”—black (2021), hues of blue, green, and black zigzag and form pockets of lime green below the surface. The didactic wall label, written by student Tenesha Carter Johnson, consults W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of the double consciousness as her starting point to dissect the work’s title, and to explore how the painting confronts the production of Black social identity. Williams covered most of the 60 x 60 in canvas with a translucent black, creating an x-ray–vision effect into the color—thin enough for viewers to see behind it. The greens play together, shifting from emerald to veridian to sap and back to black. The color peeks out as if it’s been scrubbed to reveal itself, subtly capturing a feeling of being up against a veil of pitch black, the singular idea of blackness.

During a private walkthrough, curator Karen Comer Lowe and I marveled at how Williams’ red works light up on black walls, nearly glowing. The works in the installation image above are titled What black is this you say? — “You wish you could see the black on the inside of Stevie Wonder’s eyelids so you too could have inner visions” — black (2020). Zooming into the moment described by the reds, it reminds me of closing my eyes while facing the sun. In these works, Williams speaks to the interiority of Stevie Wonder’s faculty as a blind man. For someone who truly sees only black—the same black everyone was posting in those online squares—there’s actually another world within that black abyss, one that others can’t access.

The repetitive title refrain, What black is this you say?, asks a question to which most non-Black people won’t know the answer, or how to explain the depth behind the colloquial phrases in Williams’ titles. That’s the point—they instinctively clump us all together and call us Black. Like when you mix all the colors together and end up with black. Instead of examining and acknowledging the variety of Black experiences, the exploration stops there, thus disregarding the complexity of Black identity, aesthetics, ethnicity, nationality, and socioeconomic realities. But Williams doesn’t let you disregard anything. She quizzes you, and if you fail, she teaches you something, hammering in the fact that performing activism will never work, and that having a Black friend isn’t enough. Understanding the things that led up to—and define—the contemporary Black experience is what addresses the cultural divide. Knowing how access to wealth, job security, individuality, and personal freedom has disproportionately affected Black people is what addresses the divide. A black square is lazy and denies the labor we’ve done to get here.

For more than 400 years, Black people were treated like livestock, and in 2020, we were being publicly slaughtered like livestock. To this day, when those blue lights hit our mirrors, they bring a fear that we are one power trip away from going back, from being stripped of our human rights. Williams reminds us that a black square will never describe the grief of being dealt an almost impossible hand, just as it can’t describe the dimension, resilience, and magic of all Black beings’ (including, and not limited to, African, African American, Afro-Caribbean, and Afro-Latinx peoples) capacity to face and prevail over centuries of dehumanization, displacement, invisibility, and inequality.

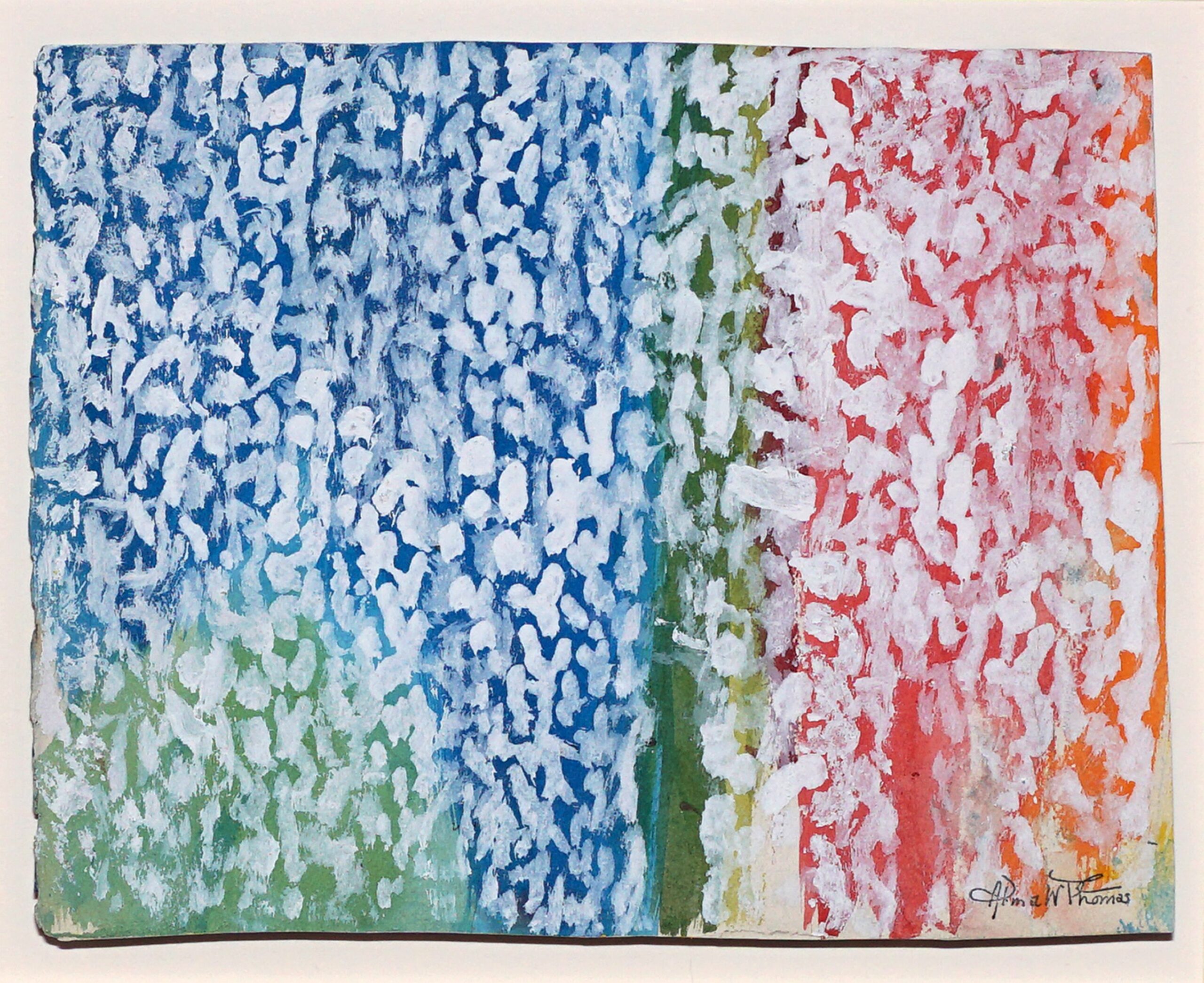

Alma Thomas, Untitled, 1973, Acrylic on paper, Lent by the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, The Cochran Collection ⓒ 2024 Estate of Alma Thomas [Courtesy of the Hart Family) / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

Thomas Sils, The Lovers, 1960, Oil on canvas, Clark Atlanta University Collection

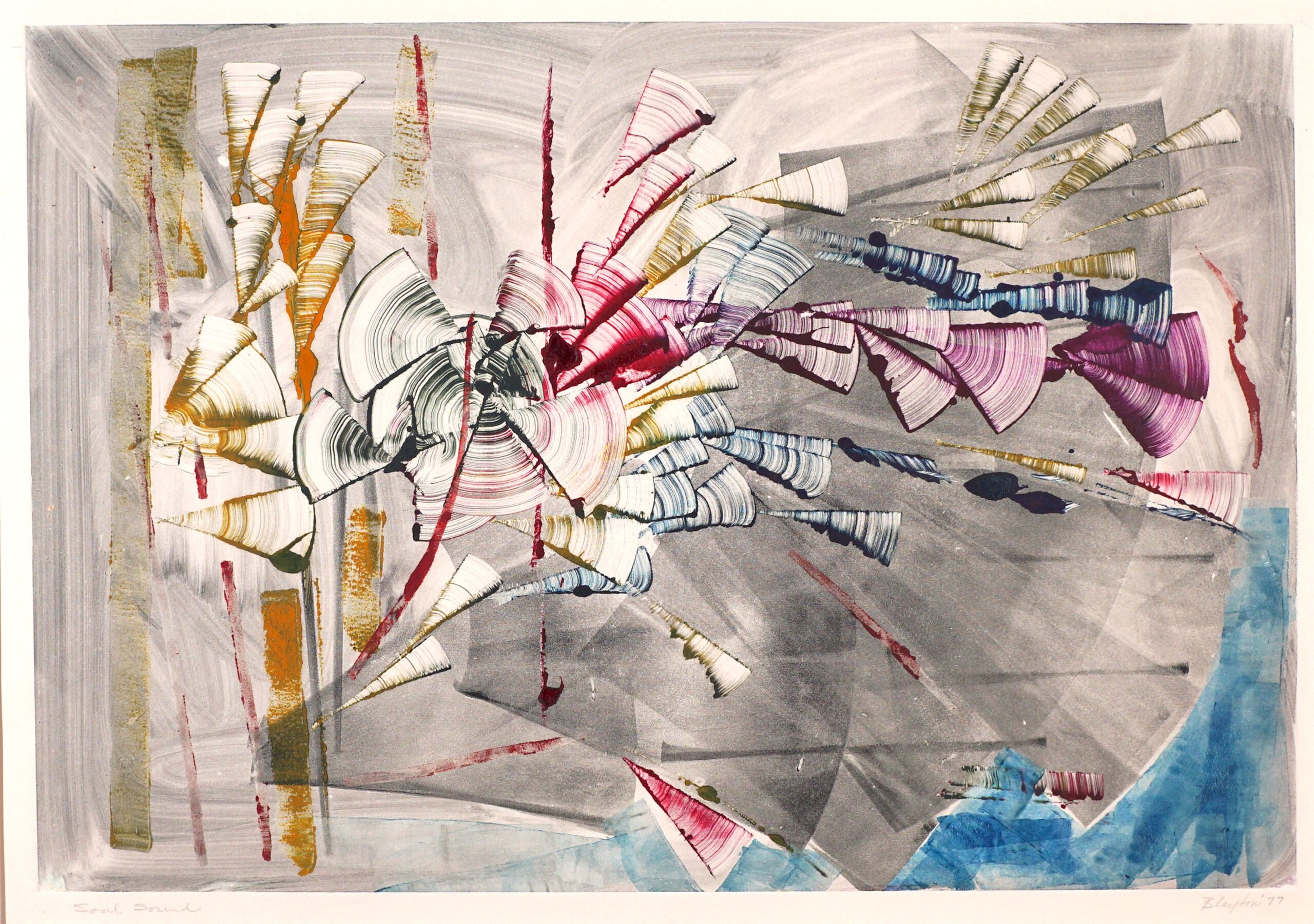

Betty Blayton, Soul Sound, 1977, Monoprint, Lent by the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, The Cochran Collection

Alongside Williams, We Say What Black This Is showcases works by Betty Blayton, Sheila Pree Bright, Beverly Buchanan, Beauford Delaney, Sam Gilliam, Maren Hassinger, Jacob Lawrence, Deborah Roberts, Thomas Sils, and Alma Thomas to present a lineage of multifaceted expressions of Black identity. Sheila Pree Bright’s photography and Sam Gilliam’s prints, in particular, present meaningful affinities with Williams’ work—Bright’s work, with its nuanced cultural memory, parallels Williams’ engagement with representation. Gilliam’s radical approach to color and form offers an art historical precedent for reimagining spatial relationships and the materiality of the painted surface.

Sheila Pree Bright, Suburbia Series, Untitled 5, 2008, Chromogenic print, Collection of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art

Bright’s chromogenic print photographs challenge conventional representations of Black life, capturing subjects in ways that defy stereotypes and assert self-determined narratives. The inclusion of her Suburbia series confronts expectations around Black middle-class identity and domestic space, expanding the conversation on who is seen and remembered in the American visual landscape. Williams similarly interrogates representation, albeit through abstraction, using color and spatial interventions, as in her Color(ed) Theory series, to reconsider the visibility of Blackness in constructed environments and underscore the presence of structural racism through redlining. In these ways, both artists reclaim the act of seeing Blackness for its range—whether through explorations of the documentary power of photography, of Black aesthetics, of socio-economic standing, or of the conceptual depth of color.

Gilliam’s screen print series Barnett Sequence 1-6 (2007) extends his investigations into color, movement, and layering, thus demonstrating his ability to translate the painterly freedom of his draped canvases into the constraints of printmaking. Through such techniques as serigraph, etching, and lithography, his prints retain the expressive, almost improvisational quality that defines his larger body of work.

Known for staining, soaking, pouring, dyeing, and splattering, Williams layers color in the prints to resonate with her use of abstraction and thereby reveal and obscure meaning. Gilliam’s title comes from a tool for measuring sea levels, the Barnett Sequence, which has a clear pattern of rock-layer stacking linked to types of sediments and gamma-ray log patterns. Gilliam mimics the process and visuals of the real-life sequence. He uses the reference to describe his technique within this series, similar to Williams’ use of the existing black square paradigm to insert her perspective.

If you examine the artists in conversation with her work, you might notice that they are all part of an effort to bring the multiplicity and undercurrent of the Black experience into a global consciousness. We Say What Black This Is is an active site of education brought to life on the grounds of a historically Black women’s liberal arts college. Take a walk through the show and be a witness; learn what you don’t know. Bask in the tints, tones, shades, and hues. Grasp that Blackness can’t be held in your hands, made simple, or boiled down. But aspects can come together to reveal a whole.

Amanda Williams, Artist and Architect, 2022 MacArthur Fellow, Chicago, IL

Samaira Wilson is an artist and writer. She received her BA in Studio Art and Global International Studies from Bard College. She regularly contributes to Elephant Magazine, and for stints at a time, is a resident at the Mildred Thompson Estate Residency, developing her art practice.