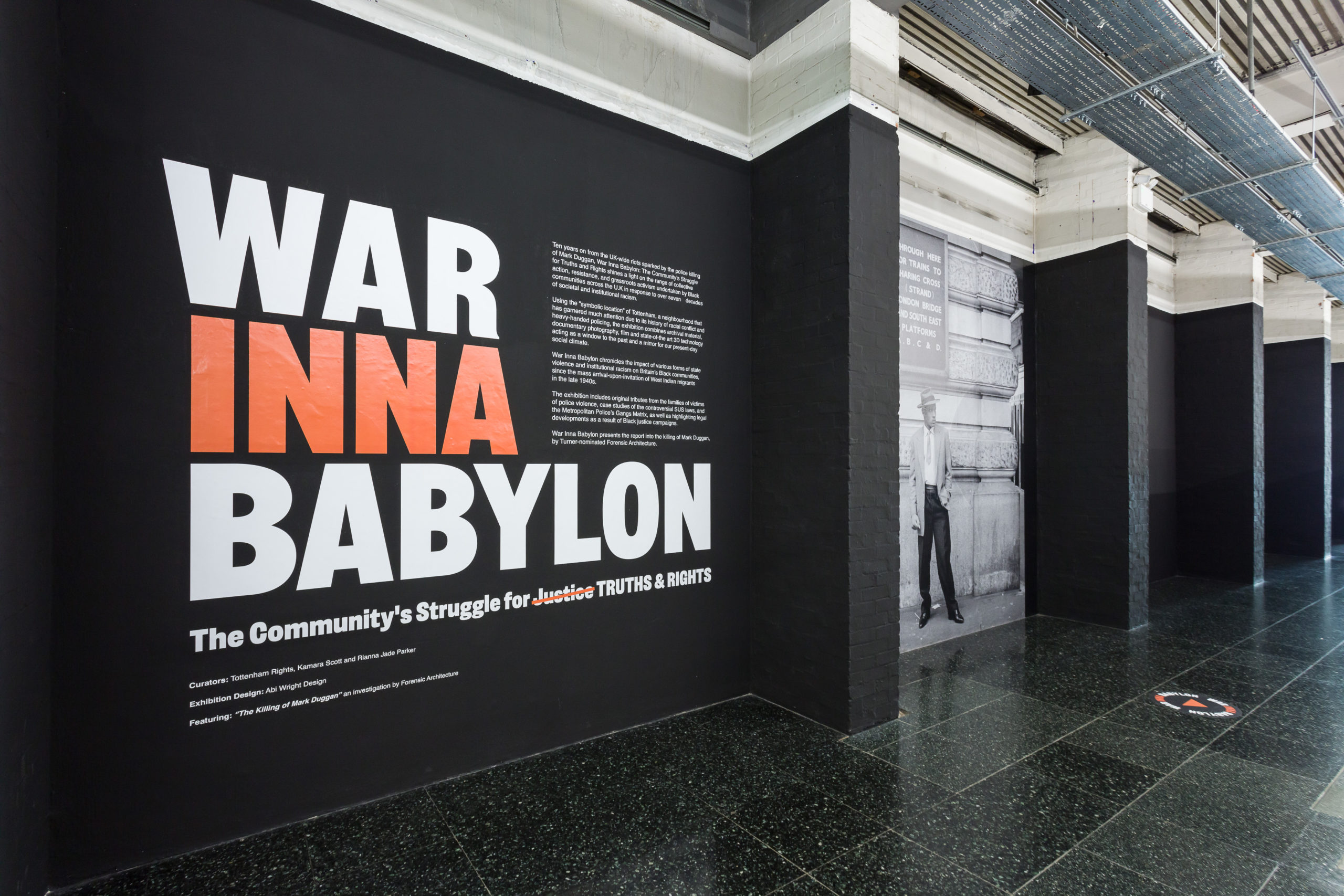

War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Justice Truths and Rights

War Inna Babylon, installation view, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

Share:

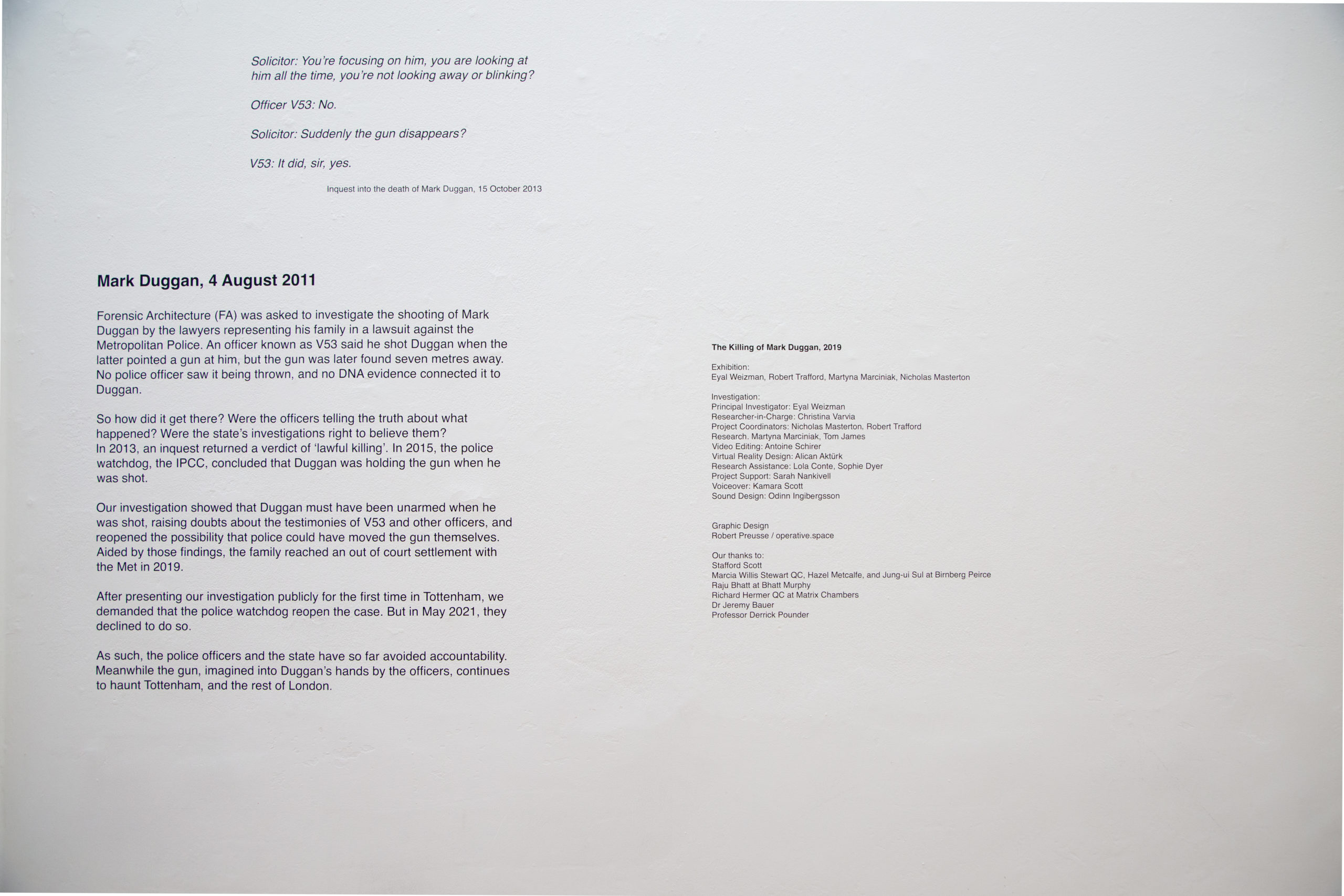

In summer 2021, London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts opened War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truths and Rights, an exhibition centering the history of institutionalized anti-Black racism in the United Kingdom and community efforts to resist it. The show departed from the so-called Windrush Generation’s arrival in the UK between 1948 and 1971. People from the West Indies came to the country at the invitation of the British government to resolve labor shortages in the aftermath of World War II. The events that followed exemplified racist policies that fueled social unrest, from that postwar moment through to the flashpoint of summer 2011, when a young Black man from Tottenham, Mark Duggan, was killed by police. His killing—whose investigation by Forensic Architecture was central to War Inna Babylon—sparked a furious uprising that culminated in a wave of prosecutions and ushered in a sharp increase of police powers against Black communities—and, in particular, Black youth.

War Inna Babylon, which broke attendance records at the ICA, was organized by Stafford Scott, co-founder of Tottenham Rights and a veteran of the struggle against anti-Black racism and police violence in the UK; alongside curators Kamara Scott and Rianna Jade Parker, and with exhibition designer Abi Wright. In the wake of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities report released by the British government in spring 2021, which effectively denied the existence of institutional racism in the UK, the project created space for a public reckoning against a blatant whitewash.

This edited roundtable stitches together discussions with Stafford Scott, Kamara Scott, Abi Wright, and Forensic Architecture’s Eyal Weizman, to reflect on the exhibition’s implications on art and activism. Although Rianna Jade Parker was unable to contribute, her participation is reflected in the discussion that follows.

Stephanie Bailey: What was the genesis of War Inna Babylon?

Stafford Scott: In a nutshell, Forensic Architecture were commissioned by the lawyers working on behalf of the family of Mark Duggan, whose killing by police shooting sparked the 2011 riots in London, to create a model to better understand the crime scene in which Duggan was killed. The lawyers tried to submit that model to the court system as evidence, and when that happened, the police offered the Duggan family an out-of-court settlement.

We believed the evidence that Forensic Architecture created was an important tool in this War Inna Babylon, because the police enjoy a monopoly over investigating themselves. We wanted as many people as possible to see this video, so we invited Forensic Architecture to Tottenham to show the community what [the collective] had created. After that, Forensic Architecture suggested we support their exhibition at the ICA. The idea was to embed the Duggan model in the campaigns we’ve been involved with as Tottenham Rights.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

SB: It’s amazing that Forensic Architecture invited Tottenham Rights to be part of their exhibition but ended up part of a show organized by Tottenham Rights.

SS: Yes, which I think they were happy with, because I don’t think they want to be perceived as people who parachute into a place and leave. We also gained from their ethos of wanting to be a part of the narrative and history of struggle. Honestly, I don’t think they really knew what they were getting themselves into, and neither did I.

The ICA asked if I could curate, but frankly I would’ve said yes to anything with a platform for us to tell our story, especially one outside of our traditional spaces and bases. I couldn’t have done this without Kamara, my daughter. Because I’m an activist, I throw everything and the kitchen sink at something; I don’t know what people would’ve seen had I been left alone! Kamara invited Rianna, who then brought in Abi. At first, we were given two months to create an exhibition, but then Covid actually gave us time to filter years of community work into a way that resonated with audiences.

SB: How does War Inna Babylon extend Forensic Architecture’s approach to using exhibition spaces as a court of public opinion?

Eyal Weizman: Our work plays out in different fora. There are obviously legal fora—some public, some behind closed doors—or more public fora, like in the media, academia, and art contexts. Each forum has a particular way to frame the evidence presented. At its best, an exhibition in an art and cultural context can communicate the long durational aspect of a split second [and] place it within the historical context. When we show work in a legal process, we need to peer deeply into the molecular level of time of the incident. An exhibition can open the political and cultural context.

When we were invited to do an exhibition at the ICA around the Mark Duggan investigation, we thought the best thing to do was to pass the platform on to an unparalleled organization that is deeply rooted to the community, who are forceful and sensitive in representing and pursuing struggles in relation to police brutality in the UK. Every different investigation needs collaboration with the people at the forefront of a particular struggle. Any exposure of facts using aesthetic, videographic, and architectural techniques would be a flash in the dark, if it did not exist within a social context, within the community that actually can mobilize around those facts.

The first time we presented the Duggan investigation to the public was with Tottenham Rights at Tottenham Town Hall, and Stafford said he wanted to take it into the heart of Babylon.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

So, although there was no previous encounter between the ICA and Tottenham Rights, we were happy to make that introduction. But that’s it! From that moment on, all the intellectual energy that went into War Inna Babylon came from Stafford, Kamara, Rianna, and Abi.

SB: Kamara, what was it like translating the activism of Tottenham Rights into a contemporary art exhibition, given your proximity to the organization?

Kamara Scott: From the get-go, we focused on how to convey what we normally do in Tottenham Town Hall or outside Scotland Yard [through] an art institution. The question was how to make an art space into a campaign space that shows how much work is done in the community to highlight injustices, but also what can be done when we join with allies in different spaces—technology, universities, and to some degree, the “art world.”

There were a lot of things to consider. We had a meeting at Tottenham Town Hall with one of my dad’s lawyers … who’s been with him since Broadwater Farm, a couple of people from Forensic Architecture, and Temi Mwale from 4Front—a youth organization in Barnet. We discussed the issues that needed to be highlighted around the Black community and Black activism in the UK, and how we could use the Mark Duggan investigation to open wider conversations to things that are current, such as the Gangs Matrix, and things that we haven’t discussed before, like the experiences of the Windrush Generation. There’s a thread running through everything happening to Black and other marginal communities in the UK, and from a Tottenham Rights perspective, there is so much evidence and material that we have first-hand, which my dad has managed to stay on top of, as one person running different campaigns over years.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

One of the main reasons I agreed to step in was because I realized that this is also my dad’s life story. He’s got 30 years of experience campaigning, a lot of the time by himself, and the reason he stays so committed is because this has been his lived experience. Your personal life is completely tied into the politics of it all, so with a project like this, it’s not just about institutional racism. You’re looking at the personal impact of it.

It’s funny, because when we started, obviously he was focused on this being a campaign, but just before the show opened he said, “I’m a curator now, I’m going to put it in my bio.”

And we were, like, “You’re a campaigner through and through, and there’s going to come many moments in the exhibition when you tell people you’re not a curator!” Because most of his work is done in public, via community meetings, and providing services to the community, this was a totally different way of communicating a message to a wider audience. But he embraced what that meant, because he really did see where the parallels are in campaigning and curating if you’re intentional and really care about it, and how these practices can coincide, and what can be done when they do.

SB: In terms of reaching a wider audience, it’s important to note the location of the ICA—between Buckingham Palace and 10 Downing Street—which brought the struggle against institutionalized anti-Black racism to the historical heart of the British Empire.

KS: People from Tottenham or Brixton, or anyone from grassroots or frontline communities who came, pointed to the National Police Memorial across the road. For them, to be in there was the significance, to have this story told so honestly, right where it all comes from. My dad always says this is not a Black story.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

It sounds simple, but we had to force our imaginations to see how we could inject soul, life, action, and history into a clinical space. We used our bodies to create imaginary walls—our arm spans—to think about how much space each section would need. It was a case of standing together and talking it through; of having many options and deciding which ones didn’t sit right over time.

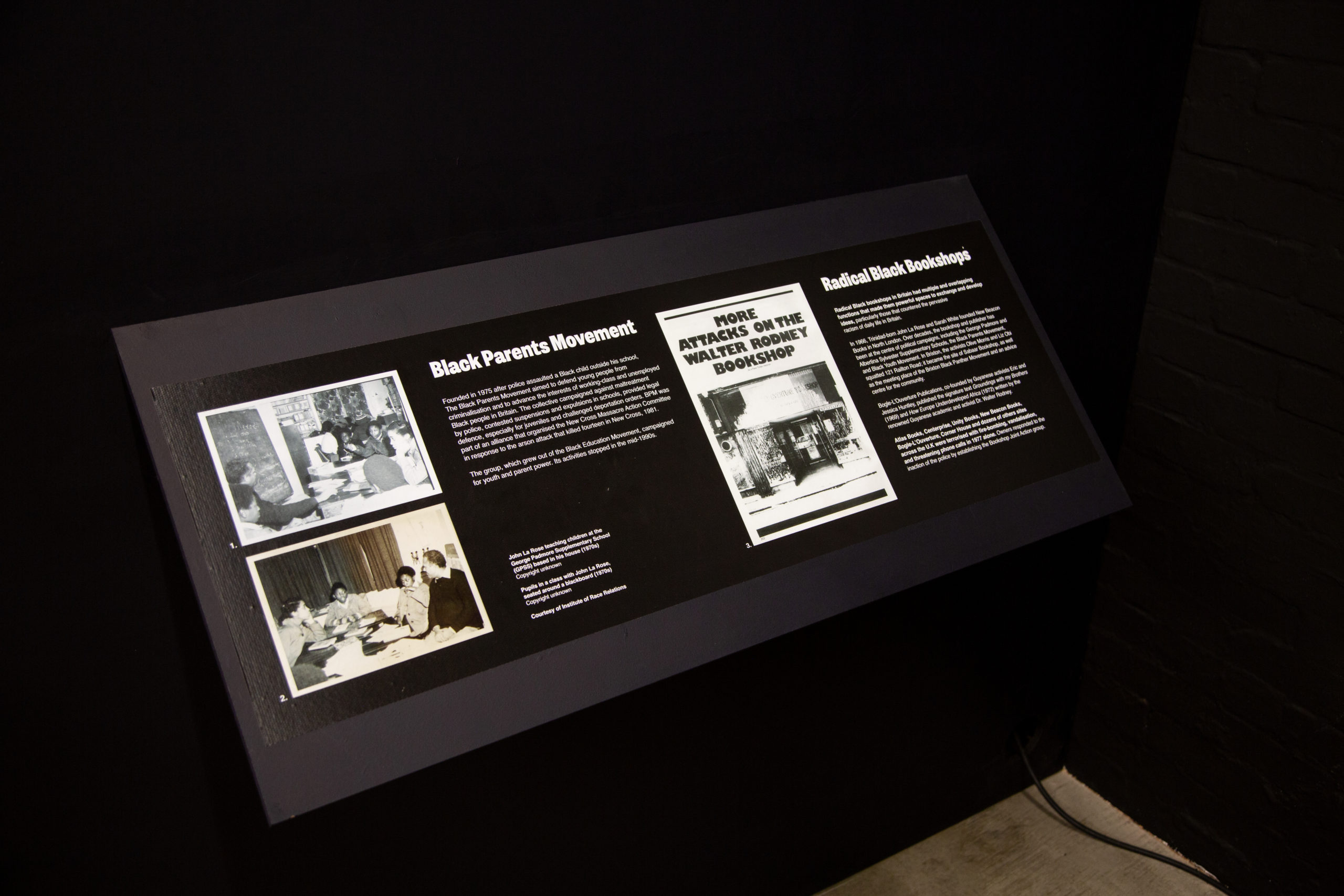

It was the same when it came to working with Rianna and Kamara in terms of content—of shaving it down over time, so that significant milestones were included in this broad picture. Aside from the Tottenham Rights archive, Rianna also had a long list of archival content that we needed to support the narrative. She got in touch with different archives around the UK and physically went to look at what they had, left, went back, and had things sent down.

This is a fundamentally British story …. The exhibition drilled that into me, [by] being right next to Buckingham Palace: This isn’t just Tottenham’s issue, this is everybody’s issue.

Stafford Scott: Absolutely, and we showed how policing in the colonies was imported to England via the North of Ireland—via Kenneth Newman, head of the Royal Ulster Constabulary and, later, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police—[and] which is still used on our community today.

SB: A quote by Newman, describing Jamaicans as constitutionally disposed to be anti-authority, was printed on one exhibition wall, one of many interventions that activated the Tottenham Rights archive. How did you work together to distill the archive of Tottenham Rights and contextualize the artworks and evidence on view?

KS: We were so intentional. To have this much space, and these resources, to tell this story was an incredible opportunity to speak to our community, while engaging new audiences. As campaigners, the material was ready to go. We just had to work out how we were going to tell this story in that space.

Abi Wright: In terms of how we worked together, it was very much circular and integrated. I remember the day we were in that space—all white, soulless even—and we had floor plans, and a really long document of all the different topics and subjects we were going to include.

War Inna Babylon, installation view, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

It’s also important to point out the emotional side to creating this exhibition. Rianna specifically wanted the cinema room to be dedicated to Menelik Shabazz and his Ceddo Film and Video Workshop collective. When he passed away, just before the exhibition opened, the whole building felt like a memorial. There was so much emotion within the walls. It was also challenging, dealing with the intensity of the subject matter every day, because we deal with it in our everyday lives, and that’s not something the institution understood or even imagined we would need support for. To come into that space and then package real-life issues in a shiny way was a really complex thing, because it’s traumatic, yet we are creating it to be consumed.

Even thinking about The Five Families of Tottenham room [which displayed footage of family members of victims to police violence, talking about the people they lost], which Kamara worked on: Because of the relationship that Stafford and Kamara have with the families, I can imagine how difficult it was to record such personal conversations. From a design perspective, it was so important to recognize the sensitivity of those stories, by giving the families their own room, making sure [that] there was a curtain at the entrance, that the room was pitch black with no disturbances, and [by] structuring the screens so they didn’t look like tombstones but had a gravity to them that emphasized how haunting, sad, and horrific their stories are. We wanted the message to be clear: Enter with care. Pay attention. Listen.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

SB: Abi, what were your core considerations when thinking about the weaving of archival documentation, evidence, historical timelines, and artworks within the exhibition design?

AW: When Rianna reached out to me, I immediately said yes, because I knew the significance of the exhibition and how it would leave a lasting impression on all the visitors who attended. I didn’t underestimate the responsibility that came with that.

Design was an important factor, but it was also my job to let the activism and history speak. The individual accounts, the trauma, the personal testimonies, the lasting effect it’s had on communities that are still there. It was my responsibility to put that at the forefront. The exhibition’s scale and all its different aspects were things I was thinking about even before I started designing. Large scale photography was a non-negotiable for me, and I had decided that the very back wall would be used for a striking image, long before the design process started. I had a short list of possibilities that I came across while image researching, but the powerful photo of Ms. Beverly Scott, the most fitting choice, was later selected by Kamara and Rianna once we had finalized the allocation of content within our floorplan.

This was really an evidence project. We were handling such sensitive subject matter and talking about people [who] still exist. So, I felt an incredible responsibility to communicate all of this important information in a very considered way, even down to the main font that I used—Salford Sans, which was designed collaboratively by David Williams, Lewis McGuffie, and Elsa Baussier, who make up type foundry Manchester Type.

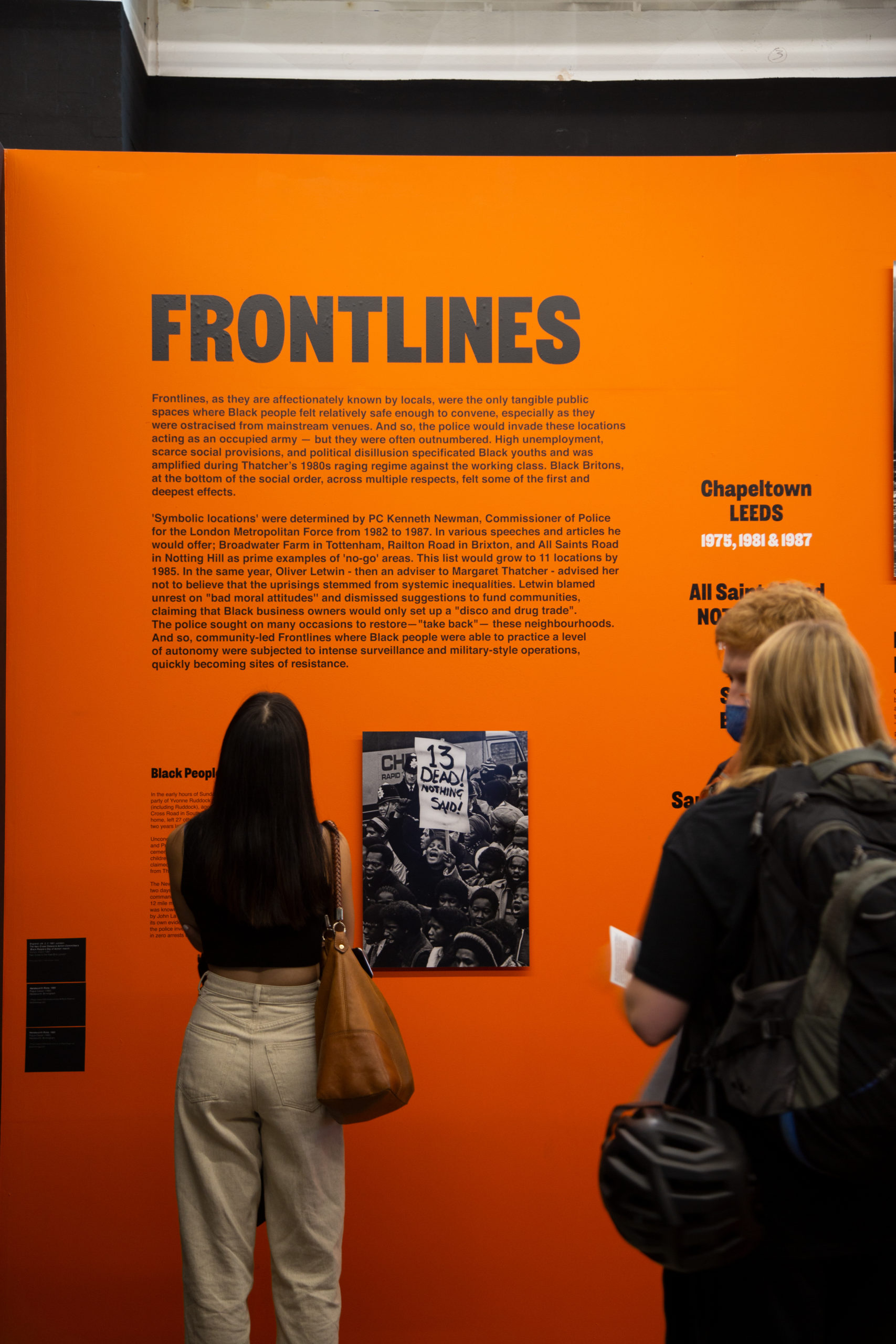

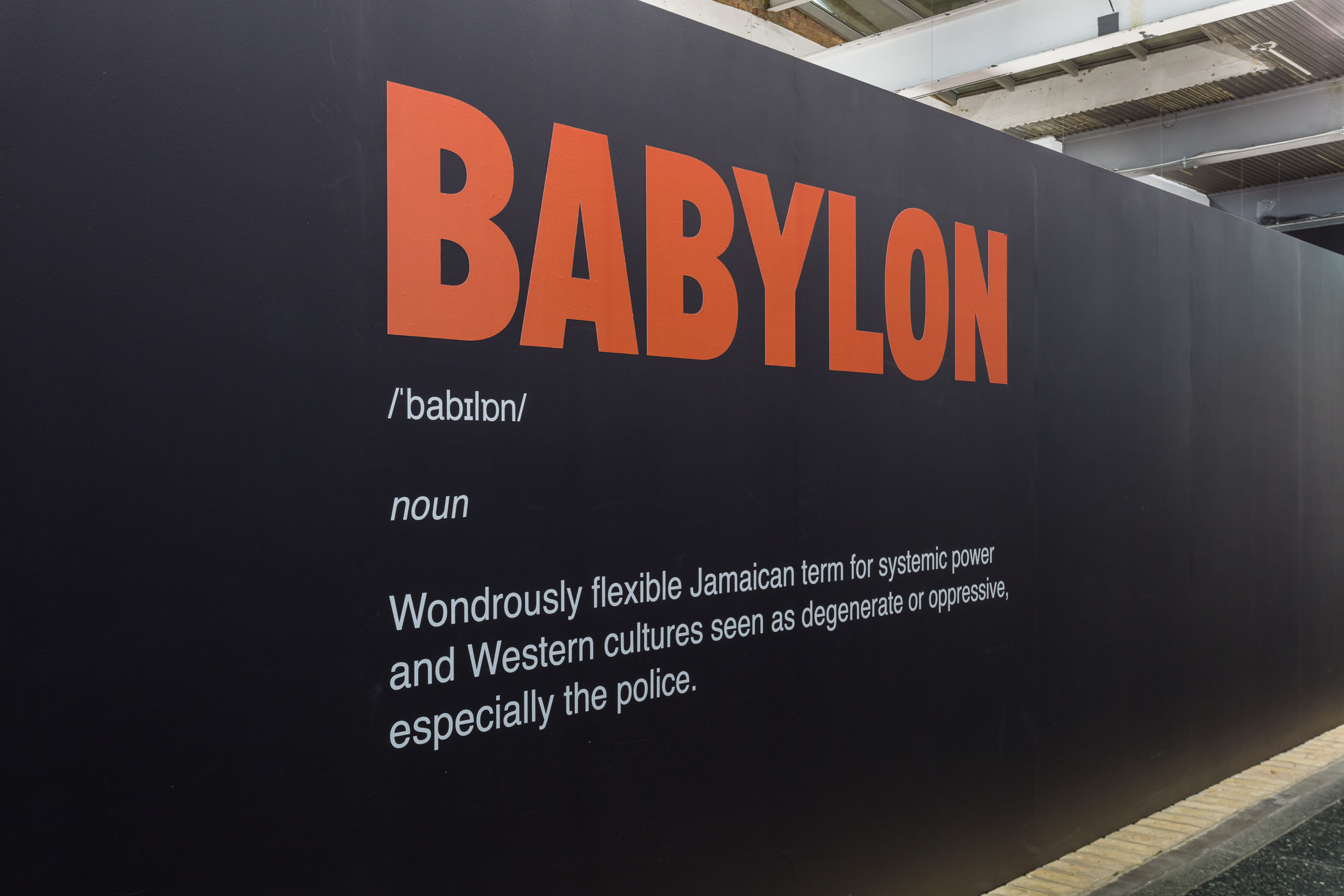

Monochrome was my starting point, as with most of my work, due to the simplicity, [the] direct and punchy impact it has when used for visual communication. A highly stylized approach for this exhibition was not needed with such important information. The shade of orange used was chosen as it symbolized movement, emergency, [literal] fire, a warning sign, discomfort even … and was a confronting contrast to the rest of the exhibition—very fitting for the period of time that the Frontlines section encapsulates and [for] the physical location within the exhibition.

War Inna Babylon, installation view, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

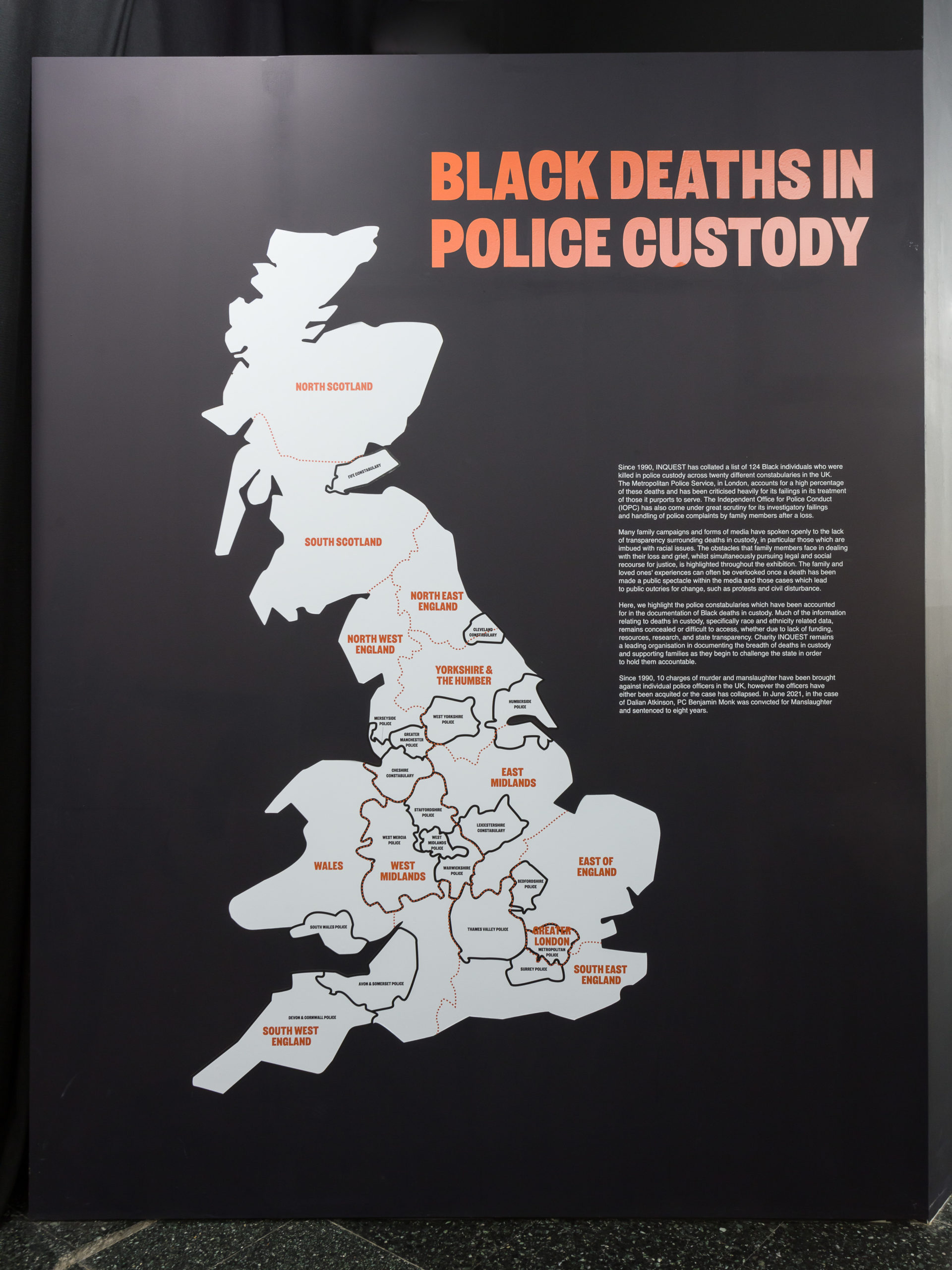

The deaths-in-custody map, in particular, took a while to tweak, purely because of how volatile and multilayered this evidence is. I needed to communicate very important—horrifying, even—statistics that required a minimal and direct design system, that could be digested quickly and easily. Whilst also humanizing the victims and family members that deaths in police custody effect. All of this information exists already in the public domain, but we are drip fed through random articles, sporadically, which makes it impossible to digest the severity of the entire picture, past and present day, if we are not paying attention. This is why our map is so important: It’s a summary of foul play over the past 50 years. It highlights the boroughs and constabularies that have significantly high numbers, it works/worked in tandem with the evidence displayed in the entire exhibition. There are no coincidences.

To have all this information in one building was definitely overwhelming, which is why [we felt] it was important we were handling it with care and consideration. Then there were points where I had to step back from the seriousness of some elements, and into the enjoyment of injecting life into other areas of the exhibition—the quotes and slogans dotted around the building, and the graphics for the program of events.

SB: How did it feel when you saw the show, Eyal?

EW: I thought, now I know how to do an exhibition. It was that powerful—absolutely unique on so many levels, from the tone, [from the] precision of the historical narrative, to moving between general issues and personal experiences, between artworks and historical documents, and [by] honoring figures such as Black Labour MP Bernie Grant. What Abi, Kamara, Rianna, and Stafford created was probably the best exhibition I have ever seen, and I feel so lucky to have been included in it.

Beyond the precision of its narration and the rhythm that it created, what was also extraordinary was how the show became the backdrop for the tours that Stafford gave a couple of times every week. The exhibition almost became a mnemonic device that Stafford put life into. Some of those tours would go well beyond two hours, and you wouldn’t notice. One of the most powerful—if not the most powerful thing—that I’ve seen in the art world is Stafford’s ability to perform history, to narrate, to move between the personal and the political, the specific and the general, [while] tying in different historical threads and showing how they affected communities and individuals. It was, honestly, mind blowing. And the public events that they put on there: I just haven’t experienced anything like that. So much at stake.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

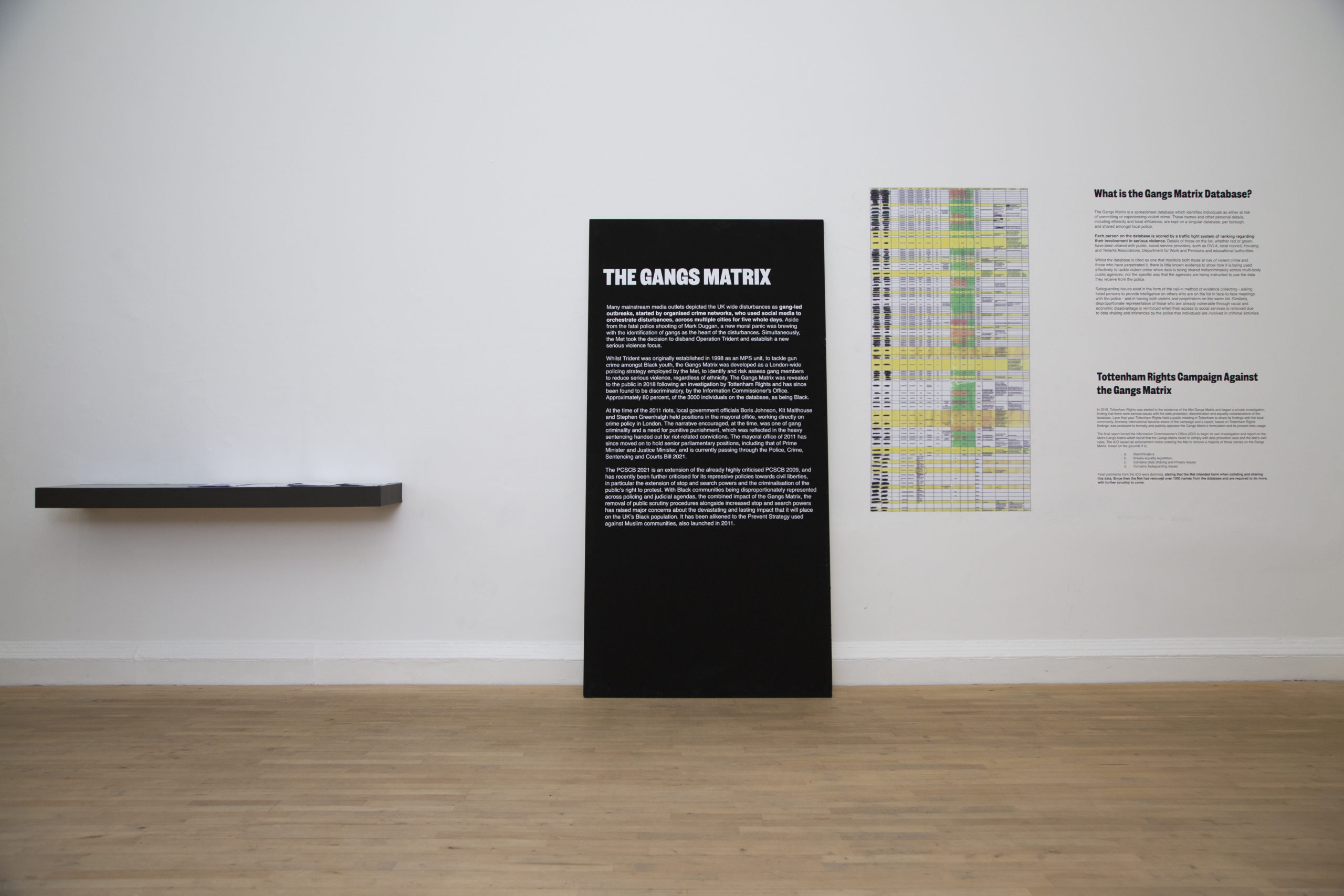

SB: The upper gallery was particularly powerful, with Forensic Architecture’s Duggan evidence presented alongside the Gangs Matrix. Stafford, could you talk about that?

SS: In 2017 we found the Gangs Matrix, which is basically a list composed, disproportionately, of Black [people’s] names, a high proportion of whom have never been arrested, who are assumed to be gangsters on the basis of association. Lives have been lost as a result of this. There were people in the database [who] should never have been there.

We shared this list with Amnesty International, who put in a complaint to the Metropolitan Police Commissioner’s office. The Information Commissioner’s Office [ICO] found the Metropolitan Police had broken privacy, data, and equality legislation, and put [those police] under special measures.

But when the ICO informed the Equality and Human Rights Commission, they did nothing, even when the police asked for assistance in conducting an equality impact assessment. And [though] we succeeded in getting the police to remove names from the matrix, they refused to inform those people, so, as far as they were concerned, nothing changed.

What we needed was [for] the ICO to look at the architects of the Gangs Matrix, which was created in the aftermath of the 2011 uprising—when Boris Johnson, then mayor of London, was given more powers over the police. The ICO actually launched a second investigation into the impact of information sharing—when police employ a third party with the intent of causing harm and distress to the target—[such as] when the police share someone’s name with their school, creating a ripple effect where they and their mates can then be removed from school, their council informed, and services [withheld] from them, [and from] their friends and families. While the ICO is conducting this investigation, Johnson is rushing the policing bill through Parliament, which carries those exact same information-sharing protocols. That’s what fuels violence in our community. If you weren’t that character they accused you of being to begin with, you’d become that character very quickly, because you need to survive.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

SB: That relates to how Justice in the wall text treatment of the exhibition title was crossed out and replaced with Truth and Rights, and the importance Stafford noted of showing Forensic Architecture’s evidence—to expand the court of public opinion and open up a broader discourse surrounding policy change.

SS: It’s about getting as many people as possible to see the evidence and open up that space for truth. There is no effective political opposition to the government right now, so it’s difficult for people to know what to do, and they understandably switch off. That’s why it’s important to get agencies such as Forensic Architecture accepted into the system, so the police no longer have that monopoly on who does, and doesn’t, receive proper justice.

But I should point out that War Inna Babylon is not an exhibition; it is an everyday lived reality. Although we’ve exhibited some of the experience, I want people to feel it, feel like they have to do something, and [then] ask what we do next. To understand that you can’t sit on the fence, because if you do, you are supporting the status quo.

The exhibition might not be the front line, but it’s a battleground, a court of public opinion, and it has started different conversations across the country. At first, we didn’t know if we could get Black people to come to the ICA—we had a deal that the community, folk from Tottenham, could come in for free—but then people started to come from all over. I’ve had teachers send essays, written by pupils after coming to the exhibition and talking to their parents about their own experiences, which has impacted relationships. We’re happy this is happening because, ultimately, it’s about change.

As an activist, I’m used to push-back. If I give out a hundred flyers, asking people to come to a demonstration, I might get ten people. There’s always some resistance. But in the exhibition, people were open. I think it was the first time many people saw the evidence laid out like this, and I saw a lot of people wake up.

SB: Kamara, what was your experience of the audience? Did anything surprise you?

KS: What surprised me were the specific types of people who didn’t come or engage; and the people who have spoken about activism or community but were reluctant to step into that space and join us in person when the exhibition opened. What didn’t surprise me was everyone else who came, because, with all the conversations that have been happening with BLM and the organizational commitments that were claimed around diversity and understanding marginalized struggles, why would you not?

Of course, I would have loved to come out of the exhibition and not have to ask what’s next, because it doesn’t lie on the curatorial team as individuals to carry it forward alone.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

But we’re not banking on anybody—we can’t guarantee that another institution will give us their exhibition space. The campaigns, as they were presented, continue. This is not stagnant material. It’s real life, and it’s ongoing, and that’s something I’ve learned from my dad. Whatever you saw in there [was] a reflection of him. There’s no money, no institution behind him. There’s him and his decision-making skills. When he decided to look at the Gangs Matrix, a copy of it happened to come to him, and that was it. He said everybody was going to know about it, and we’re getting people’s names off that list.

SB: Has bringing the activism of Tottenham Rights into the art institution opened up new avenues for the work to move forward?

SS: The response has been so overwhelmingly positive that we are considering ways to do this again with the ICA, and independent of the ICA. I certainly want to bring this to other cities across the country, especially where uprisings have happened, such as Moss Side in Manchester, Handsworth in Birmingham, and Toxteth in Liverpool.

We smashed every visitor record at the ICA. Twelve thousand people came to the exhibition in twelve weeks, including August, which is allegedly a dead month. So there’s a real appetite for it. A lot of people [whom] we didn’t know existed now know that we are here, and vice versa, which has been really powerful.

We’ve been contacted by organizations from everywhere, and have been asked to present the project at universities and other institutions. We also seem to have built a credibility with funders who came to the show and are now talking about possibilities for the future.

SB: That point about funding relates to an issue often raised in the arts when it comes to working with institutions like the ICA and effectively serving their interests. But, in this case, the art system worked to your advantage as activists.

SS: Of course. We could never have put together this exhibition without the backing of the ICA. No funder would have supported us. Now we can show funders what’s possible with a credible proposal, whereas before they would have laughed at us.

But the ICA have a lot to learn from our exhibition. They want to believe they are radical, but when we got there, we found a bunch of traditionalists. I mean, lovely individuals, but there were times when we felt disrespected. I got the sense that we were in the way, that the way we did things was not how things are usually done. Curators curate, and then they go, is what I was told. But I’m not a curator, I’m an activist, and the ICA need to get their curators to do what we did in there. Take the tours: After we put up the show, we could see people didn’t know how to walk around the space. It became obvious [that] they needed guidance to understand what they were seeing, so these tours started organically. The institution didn’t expect that.

Then, after we set records in August, we started getting more people, and a lot of them would come after work. We asked for the bar to stay open a bit longer, because the walkabout could take a few hours. There were days when I’d come down with 50 people and we couldn’t even get a drink of water. Eventually, they left water for us in a space for me to get, but even that felt disrespectful.

Us an Dem, dir. Rianna Jade Parker, ed. Daniel Amoakoh, UK 2021, 13 minutes [photo by Mark Blower]

SB: This recalls an issue at the recent Athens Biennale, when artists from Baltimore complained about their mattress at their Airbnb. As one local activist pointed out, a mattress isn’t just a mattress, just like water isn’t just water; it’s about the cultures of care and how an institution works with communities.

SS: Yes. It’s about principles. It’s about working together to decide how we go about doing things. So, the bar won’t stay open, but we’ll chuck some water in a corner—that’s not the way to build community. We could have brought in people to serve drinks, for example, but they weren’t willing to flex. True collaboration means not making assumptions, and the assumption was that they were the host, and we were the guests. Of course, there are no bad people there. The institution just has its way of doing things. But I felt that they invested in the exhibition, and not in us. They didn’t quite understand us.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Mark Blower; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

SB: There are those in the arts who will write off an exhibition like this because it fits a narrative that institutions use activists to show they are evolving, without engaging in any real systemic change; that projects like this have no aftereffect or benefit to the communities being foregrounded. What would you say to that?

KS: I feel like that criticism speaks more to whoever is saying it than it does to the people they are speaking about. While, of course, it does apply sometimes, if we had the general luxury of talking about it all day and whittling it down to [question] which institutions are acceptable and which aren’t, we wouldn’t be doing the work we are doing.

If this opportunity to put everything we’ve ever done into one room can be tainted by the fact that it’s been done in an art institution, you actually have to say: Fuck the institution. My dad deals with the police, he deals with the legal system, and families who have experienced deaths in custody. There is such urgency with these issues, to tell the stories and make our voices heard, that sometimes—just sometimes—it doesn’t matter where you’re doing it. That whole place became a timeline of evidence, of campaigns where activists and community have met and made things happen, because there’s a meeting point.

You have to look at the exhibition and the impact it had, whether educational or having people join us in our work; that’s what happens when activists can speak to community, and when they have the space to create community. It would be nice if we could speak to the thousands of people who came to the exhibition outside of Scotland Yard when we’re protesting, but those people don’t show up. They showed up for George Floyd, after BLM took off; they showed up on the internet. But they didn’t show up in real life.

On the campaigning side, it doesn’t matter where it is; what needs to be said, needs to be said. The fact that it was at the ICA, on the same road as Buckingham Palace, is significant for us because that’s not somewhere we can protest. We are on the fringes; 99% of what we do is out here speaking to our community. It might be hard for people to understand, but this was a campaign that happened to be in an exhibition space, and that’s not to say anything about what an exhibition space should and can be. But when you’re campaigning, it is what it is, and you do what you have to do.

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

War Inna Babylon, installation detail, 2021 [photo: Christa Holka; courtesy of Kamara Scott, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Tottenham Rights]

EW: It’s always disappointing to see people holding only one thought in mind, because other things are going on at the same time. An exhibition comes out of multiple interests. There are many people involved. You cannot reduce it to the cultural politics of the art world. Of course, there is the problem of virtue signaling, but it is reductive to say that, because some in the art world do stupid things, like capitalize or commercialize, everything you put in the art world is contaminated by it. It is disappointing that this kind of critique cannot acknowledge what was assembled here. Although the show broke attendance records, it was a very different crowd from the regular art circle.

That said, for War Inna Babylon to be produced, continuous conflict with the institution was necessary. Deep structural problems were manifesting as curatorial and production problems. The art world has habits that need to be broken. To turn the art institution into an effective platform, an effective political space, you have to struggle with these institutions, or against them, and we saw that with War Inna Babylon. An institution in the center of London was occupied and activated by a political-aesthetic energy. The fact [that] something like this happened, shows how cultural institutions could be. We were shown another possibility of being in the art world that is not reduced to superficiality, to virtue signaling, or to its stereotypes. That’s how we need to occupy our art spaces.

Editor’s Note: In the print edition of ART PAPERS 45.03 Gaming the System, on the cover page of the interview “War Inna Babylon, the Community’s Struggle for Justice Truths & Rights,” the featured image was incorrectly captioned as an installation view. It should have been credited, as it is shown above: Us an Dem, dir. Rianna Jade Parker, ed. Daniel Amoakoh, UK 2021, 13 min., English, photo by Mark Blower.

Stephanie Bailey is editor in chief of Ocula Magazine, a contributing editor at LEAP, and a regular contributor to Artforum International, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, and dɪ’van: A Journal of Accounts. Formerly the senior editor of Ibraaz, where she worked 2012–2017, Bailey is also a member of the Naked Punch editorial committee; a managing editor of Podium, the online journal for M+ in Hong Kong; and the current curator of Art Basel Conversations in Hong Kong.