Valley Visionaries

Photo: Gilda Davidian

Share:

I met Gilda Davidian, Meldia Yesayan, and Mashinka Firunts Hakopian at Urartu Coffee in Glendale, CA, on August 5, 2018. The subject of our conversation was the controversial exhibition Vision Valley, on view in Glendale’s Brand Library & Art Center, a show “conceived and organized” by The Pit gallery. Glendale is a historically Armenian suburb adjacent to the city of Los Angeles, where thousands of displaced Armenian migrants sought refuge: an estimated 30%–40% of the city’s residents are Armenian, making it one of the largest communities of Armenians in the US. Davidian, Yesayan, and Hakopian all have ties to Glendale’s communities. Yesayan and Hakopian grew up there, and each has family members who continue to reside in Glendale.

In an essay published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Hakopian writes, “Theories circulate about why the diasporic community crystallized in Glendale. My mother would say it’s because the valley views approximate the mountainous topographies of Armenia. The valley, as she said, visually softens the losses of territorial dispossession.” The essay, and a subsequent open letter published by Hyperallergic, brought Davidian, Yesayan, and Hakopian together to oppose the forces of gentrification and cultural erasure in the city of Glendale. Together, with Armenian cultural workers and community activists, they are co-founding Artar, a collective based in Los Angeles that aims “to bring visibility to Armenian diasporic cultural output; to stand with our communities against erasure, displacement, and gentrification; and to stand in solidarity with other communities locally and globally whose survival is threatened by these forces.”

In response to complaints from the community, the city asked The Pit to remove “Glendale Biennial” from the name of the exhibition, which is now known as Vision Valley. But the driving impulse behind the show—to showcase art in Glendale—ultimately resulted in a historically diasporic community being rendered invisible through the failure to include Armenian artists in the exhibition, exposing even more disquieting realities about the nature of art and community.

Sara Wintz: How did you meet?

Meldia Yesayan: I saw a post about the Vision Valley show a month before it opened at the Brand Library & Art Center. When I saw the listing of artists it struck me as really odd [that the show didn’t include Armenian artists]. I emailed a few city leaders and others in the city involved in the arts, and, not really finding anyone who was equally unsettled, I figured, if no one else seems to think this is problematic then maybe it’s not so problematic. Soon after Mashinka emailed me and said, “I am writing an article about this and would you talk to me for a while?” I didn’t know Mashinka. I said “Sure, I am happy to talk and share what I have found, but I don’t know if it’s that helpful ….” We started talking, and spent hours going over the history of culture and migration in Glendale. Lost spiritual connection. And then Gilda … how did we ….

Gilda Davidian: We met because you emailed me.

MY: Yes, Gilda was one of the first people I emailed. Gilda was actually the only person who agreed and said, ‘This is crazy, we have to do something about this.” And I said, “Of course, this doesn’t make any sense, what do we do?”

GD: We were both wondering, “What do we do? What is the next step?”

MY: I wrote a letter and said, “Gilda, should we circulate this letter?” We weren’t sure if it would make a difference. Then Mashinka came into the picture.

MFH: It was a serendipitous meeting. The first hours-long conversation with Meldia, and the correspondence with Gilda …. When the three of us finally gathered in person, it was a reunion of old friends meeting for the first time.

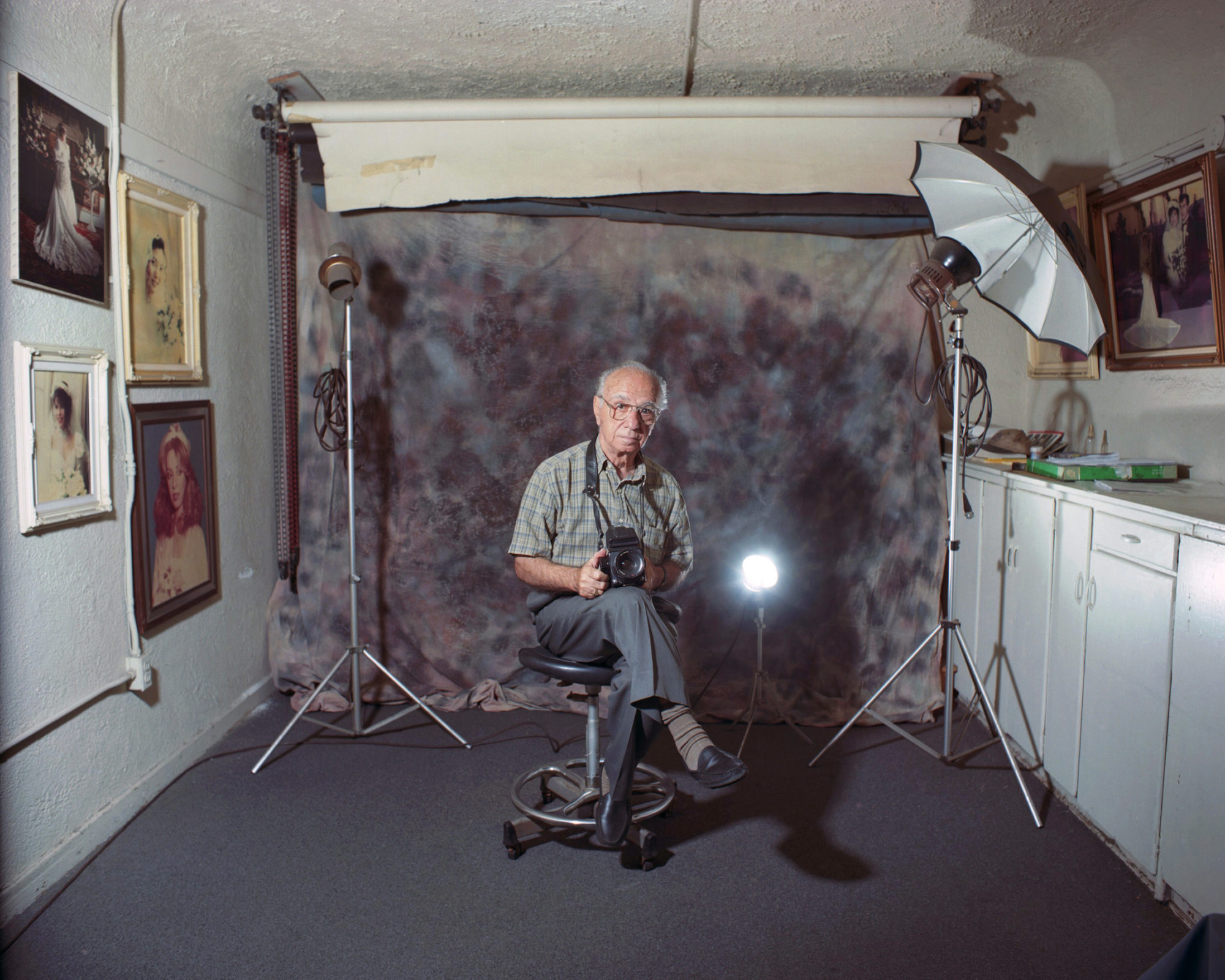

Gilda Davidian, Photo Aram, Glendale, California, 2011, from the series Portrait Studio [courtesy of the artist]

SW: What was the first concrete step that the three of you took together?

GD: I think it was when Mashinka contacted us for her essay.

MY: Prior to that, I had emailed the Brand Library & Art Center director, who essentially said, “We are moving forward with the show, we will not change anything, I support this, this was my decision, and I stand by it.”

I said, “Great, if this is something you, your supporters and the city of Glendale are behind, then good luck.” That was prior to Mashinka and I connecting. I don’t know how she felt after she read the essay. Perhaps, in retrospect, they might be thinking about how they could have handled this differently.

MFH: I was doing research for the essay, and I came across a post that Gilda had made on Instagram that was an incredibly insightful, forceful account of the implications of the show. Gilda then put me in touch with Meldia.

I was writing the essay, but we were collaboratively sharing resources and stories and dialogue. That dialogue was transformative, because none of us had imagined that our individual response might be shared or collective. Meldia and Gilda were the first people I spoke with who recognized what an exhibition like this meant as a gesture in a community that is rapidly transforming.

SW: [to Gilda] What did your post say?

GD: In the first post, I said that I thought it was unacceptable that this was happening, that it was colonizing on the part of The Pit to call the exhibition “The Glendale Biennial” while ignoring such a significant part of the population of Glendale, while including their own directors and gallery associate in the exhibition.

SW: In the art world that is just not done, after an open call, being in their own exhibition.

MFH: A commercial gallery using municipal funds and space to facilitate a show that includes their own employees.

GD: In my emails to The Pit, I asked them to change the name of the exhibition. I thought it was better suited to call the exhibition The Pit Biennial. I thought it was irresponsible and pretentious to take the stance that they did, to claim to represent the entire city of Glendale through their art show, and, in their way, to “present” what contemporary art is to the city. Their responses to my emails were gruff and dismissive. They didn’t respond to my second email but soon after I noticed that “Glendale Biennial” was removed from the exhibition’s title.

Gilda Davidian, Witness, 2013, from the series Secondhand Witness [courtesy of the artist]

SW: It sounds like they listened at first.

GD: That was what I thought, but it wasn’t what happened.

MY: It was [what happened] once there were a few public posts [on social media], not from any of us, but from non-Armenians, saying, “No Armenians?” or “A Biennial in Glendale with no Armenian artists?” That was when the name change occurred.

SW: So they weren’t listening to the Armenians?

All: No, they weren’t listening to the post either; the name change was at the behest of the city.

MFH: That was a clear indicator they didn’t recognize the legitimacy of any community members as interlocutors, but were willing to recognize the legitimacy of the city and its officials.

GD: At first I thought, “They’re listening! They understood.” But no, they weren’t. The Pit never responded to my second email, and they continued to use the #GlendaleBiennial hashtag. When I commented on an Instagram post, asking why the hashtag was still being used if “Glendale Biennial” was removed from the title of the exhibition, they blocked me. I’m still blocked from their account.

MFH: They proceeded as though they weren’t accountable to any of the residents of the city they purported to represent.

GD: Like they were putting Glendale art on the map.

MFH: It’s significant that this is happening in a city that already has [at least] five Armenian-run or Armenian-owned or Armenian-inclusive art galleries, and that it is happening in that city at a time when economic transformations are making it impossible for many, many members of the Armenian community to continue to live there. None of these dimensions of Glendale are addressed in the exhibition. The Glendale Tenants Union just formed last year and has been actively combating these issues, but the gallery’s position—which is representative of a broader tendency in the art field—was, “We are outside the economic, we are outside the political, we operate in autonomy from those spheres.”

SW: It also brings into question the borders of community and art. Did you ever feel like the show was dividing the community or shaping new borders of where the community is and is not located? [Of] who lives in Glendale and what Glendale is?

GD: I know that many of the artists in the exhibition don’t work in Glendale. The Pit kept it fuzzy as to who and what Glendale artists are. The geographical location that The Pit highlighted is where their location is, not necessarily where the artists in the exhibition are from or where they work.

MY: I think many of the artists neither work nor live there.

MFH: I think maybe a few [people laughing and agreeing].

GD: I think the representation was more around Glendale than in or from Glendale. The Pit was casting a wide enough net to get the artists they wanted to associate with, that represented them.

Gilda Davidian, Photographs from EdoArt Archive, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

SW: It really comes back to what you said, Gilda, about colonization. They are coming in with what they want to bring to the community without thinking about what is already there. The Los Angeles Review of Books essay brought you together in this shared cause. What happened as a result of the open letter?

MFH: That was when we decided to form a collective to address the visibility of Armenian diasporic output, and the cultural and economic erasure of Armenian diasporic communities in and beyond Glendale. Moving away from this specific exhibition, which we see as symptomatic of a much broader tendency that needs to be addressed.

MY: To me the signifier that their public response or “apology” was meaningless, was their inaction when we raised these same issues, albeit privately, and they were indignant.

There have been past shows at the Brand Library & Art Center without Armenian representation, but those didn’t raise the concerns that this one did. This show was framed as a cohesive, community-based show, inclusive of and representing the community. [It] seemed really disingenuous because there was really none of it—that was the striking difference.

For me personally, that’s what struck a chord. My parents and I moved to Glendale as immigrants in the late 70s. I grew up in that community, blocks from the Brand Library. It was where I took my first art classes, my first ballet classes. It was kind of my art home base. Now, as an adult working in the arts, it is quite emotional to see the space that I always thought [of] as representing my cultural beginnings, mounting a show holding itself out to be a community exhibition of artists, where I couldn’t see anyone reflecting me. That felt really uncomfortable.

MFH: The one point that I would flag is that this show is staged at a municipally funded space, whose designated function is to serve Glendale’s publics. Exhibitions in public space participate in determining who is included in the notion of “the public.” The total exclusion of Armenians in this context redacts them from Glendale’s publics.

Again, this cultural erasure is happening against a backdrop of much more pervasive and structural transformations in the city. It’s untenable for cultural institutions and commercial art spaces to position themselves outside of the economic situation unfolding in Glendale—and Los Angeles more broadly—which is one of rapid, inequitable development and gentrification that is displacing immigrant communities, communities of color, working class communities. Coalitional efforts like Defend Boyle Heights and the Chinatown Community for Equitable Development have formed in recent years to address those conditions.

I mentioned the Glendale Tenants Union, which I’ve been involved with, and right now at the Windsor Court apartment complex in Glendale, 60 families are facing eviction because the rent increased $800 … overnight—60 families. At another complex in Highland Park, Avenue 64, there is a rent strike going on because of a several-hundred-dollar rent increase. One of the people we are forming this collective, Artar, with, Hayk Makhmuryan, is a longtime community activist and a core member of the Glendale Tenants Union. When I was putting together the LARB essay, I asked him: “What [damage] do you see?” He responded that cultural erasure and economic erasure go hand in hand, and I could not agree more. The effects here are not just symbolic. They participate in a much larger system of interwoven economic and cultural erasure. It’s not by accident that an exhibition like this launches at the same time that diasporic communities are finding it impossible to sustain their existence economically.

Gilda Davidian, Photo Aram, Glendale, California, 2011, from the series Portrait Studio [courtesy of the artist]

SW: How has this community shaped you? How does being Armenian shape who you are and what you do?

GD: Being Armenian shapes every aspect of who I am—in my thinking, my family, my work. There is no way that I would be able to separate that from what I do. I don’t even know how to articulate it in any way, other than it is who I am. And these spaces are really important to me.

I grew up in Pasadena. I barely spoke English until I started elementary school. The place that I come from, [where] my family lived for generations, no longer exists. We don’t have a place to go back to. What does exist is where my parents placed me and the community they built there. In that way, my family and our community is where I am from. It is our land, and we carry that with us. That is something crucial to our existence, and in many diasporic communities. We create places in order to continue to exist.

MY: As an Armenian born in Iran, I am part of a long history of displacement that continues to this day. I think the result of multiple diasporas and transgenerational displacement is that one wants to find a place to call home. I always felt that I could call Glendale home, no matter where I lived, whether I was in New York or LA. That is what you take with you as a diasporan, where you have been forced to move, this experience of simultaneity. But when there is a displacement from that home, whether you live there or not, then what happens? Where is home?

MFH: To follow on Meldia and Gilda, the history of Armenians is a history of diasporic dispersion. We are accustomed to displacement and dispossession as a condition of our collective cultural experience. My mother was an immigration paralegal who worked with Armenian asylum seekers for 20 years, who helped to establish Armenian communities in Glendale. She used to meet her clients here, at Urartu. Glendale is 40% Armenian. It is [home to] the largest diaspora of Armenians in the US. There are more diasporans living outside of Armenia than there are living in Armenia. Displacement takes many forms. Cultural erasure is a kind of displacement. It displaces the cultural history of a city and, again, participates in an economic system that is materially displacing the residents of the city. But, as Gilda and Meldia said, Armenians have actively fought to maintain a connection to their cultural identities, which are not understood as monolithic but as porous and manifold, perpetually shifting across generations and ongoing diasporic dispersions.

Gilda Davidian is a photographer living in Los Angeles. She received her MFA from the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College. Her practice asks questions about the relationship between photography and memory, and how we come to understand histories and locations through images. Davidian’s work has been included in exhibitions at Visitor Welcome Center, the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, the Kerckhoff Art Gallery at UCLA, the Center for the Arts Eagle Rock, and the Hessel Museum of Art in New York. More of her work can be seen at gildadavidian.com.

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian is a writer, artist, and PhD candidate in the history of art at the University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Los Angeles, where she teaches in the Department of English at UCLA. She is a founding member of the performance group Research Service alongside Avi Alpert and Danny Snelson, with whom she has presented projects for the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, and The Drawing Center in New York. She is a contributing editor to ASAP/J, and her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Art in America, Los Angeles Review of Books, Performance Research, Cinema Journal, and elsewhere.

Sara Wintz is the author of Walking Across a Field We Are Focused on at This Time Now (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012) and The Lauras (sus press, 2014). Her writing has appeared in magazines and anthologies including It’s night in San Francisco but it’s sunny in Oakland (Timeless, Infinite Light, 2014) and Chicago Review. Her previous interviews with Dodie Bellamy, Cheena Marie Lo, and Zoe Tuck are available on the Poetry Foundation’s website.

Meldia Yesayan is a cultural producer living in Los Angeles. She is the current director of Oxy Arts, the multidisciplinary arts programming initiative at Occidental College. As an arts administrator, she has a particular interest in forging cross-disciplinary partnerships and expanding contexts and access to the arts. Prior to Oxy Arts, Yesayan held leadership positions at Machine Project, Sotheby’s Auction House, and MUSE Film and Television, and she was a consultant for numerous arts organizations in Los Angeles and New York. She holds a BA and JD from UCLA and worked for private law firms in LA and New York for seven years before entering the field of arts management.