Valerie Maynard

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS July/August 1990, Vol. 14, issue 4.

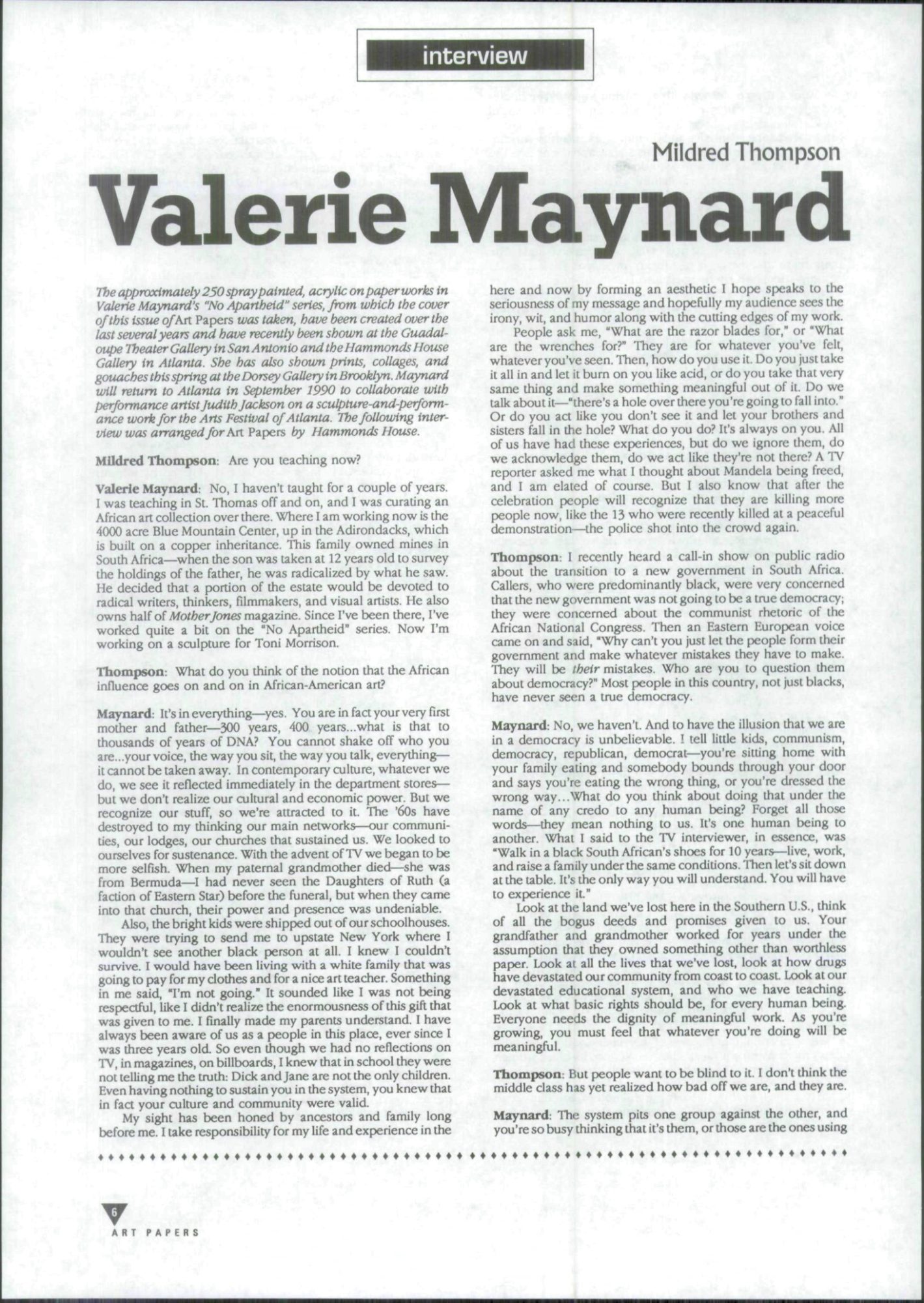

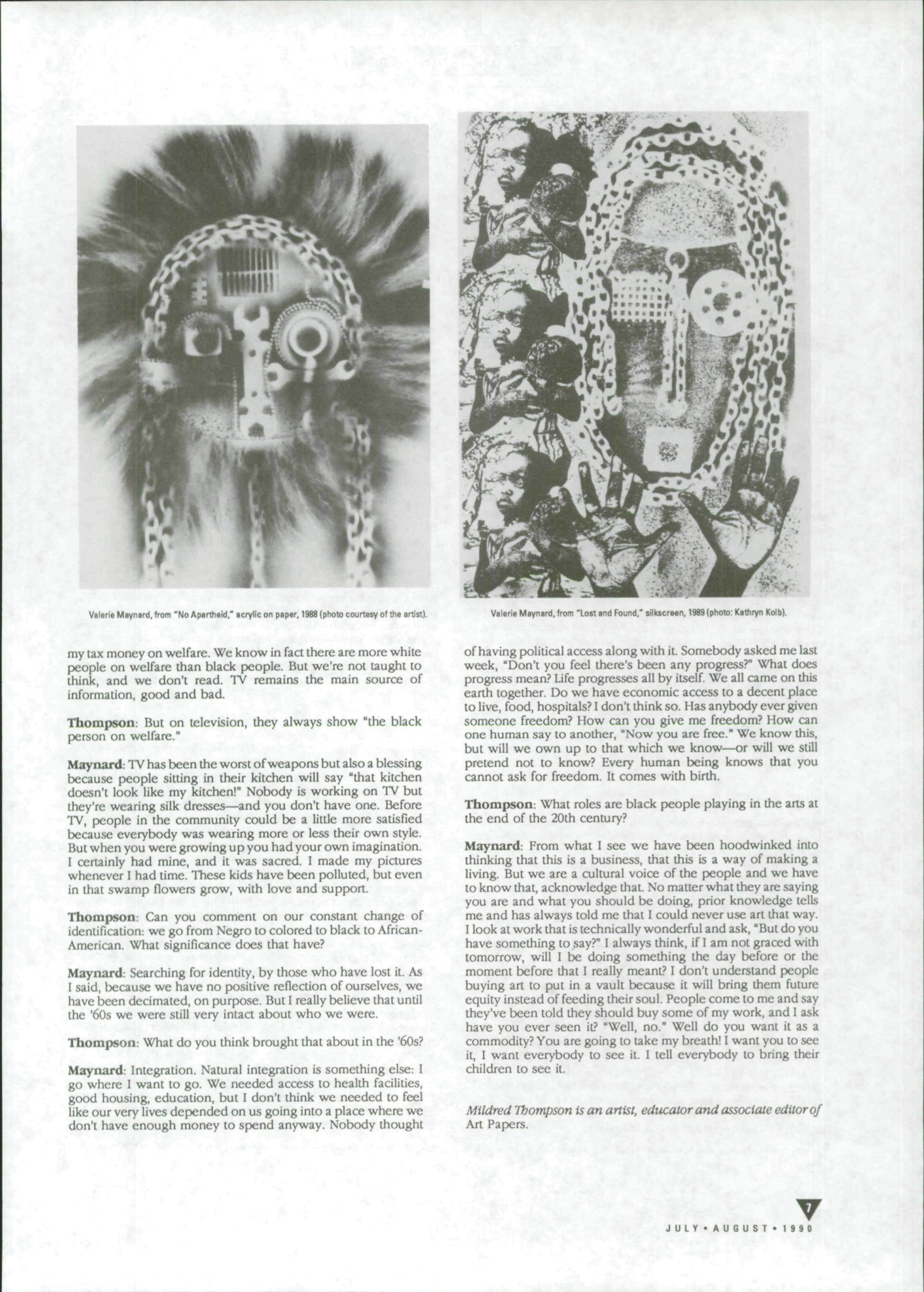

The approximately 250 spray painted, acrylic on paperworks in Valerie Maynard’s “No Apartheid” series, from which the cover of this issue of Art Papers was taken, have been created over the last several years and have recently been shown at the Guadaloupe Theater Gallery in San Antonio and the Hammonds House Gallery in Atlanta. She has also shown prints, collages, and gouaches this spring at the Dorsey Gallery in Brooklyn. Maynard will return to Atlanta in September 1990 to collaborate with performance artist Judith Jackson on a sculpture-and-performance work for the Arts Festival of Atlanta. The following interview was arranged for Art Papers by Hammonds House.

Mildred Thompson: Are you teaching now?

Valerie Maynard: No, I haven’t taught for a couple of years. I was teaching in St. Thomas off and on, and I was curating an African art collection over there. Where I am working now is the 4000 acre Blue Mountain Center, up in the Adirondacks, which is built on a copper inheritance. This family owned mines in South Africa—when the son was taken at 12 years old to survey the holdings of the father, he was radicalized by what he saw. He decided that a portion of the estate would be devoted to radical writers, thinkers, filmmakers, and visual artists. He also owns half of Mother Jones magazine. Since I’ve been there, I’ve worked quite a bit on the “No Apartheid” series. Now I’m working on a sculpture for Toni Morrison.

Thompson: What do you think of the notion that the African influence goes on and on in African-American art?

Maynard: It’s in everything—yes. You are in fact your very first mother and father—300 years, 400 years…what is that to thousands of years of DNA? You cannot shake off who you are…your voice, the way you sit, the way you talk, everything— it cannot be taken away. In contemporary culture, whatever we do, we see it reflected immediately in the department stores— but we don’t realize our cultural and economic power. But we recognize our stuff, so we’re attracted to it. The ’60s have destroyed to my thinking our main networks—our communities, our lodges, our churches that sustained us. We looked to ourselves for sustenance. With the advent of TV we began to be more selfish. When my paternal grandmother died—she was from Bermuda—I had never seen the Daughters of Ruth (a faction of Eastern Star) before the funeral, but when they came into that church, their power and presence was undeniable.

Also, the bright kids were shipped out of our schoolhouses. They were trying to send me to upstate New York where I wouldn’t see another black person at all. I knew I couldn’t survive. I would have been living with a white family that was going to pay for my clothes and for a nice art teacher. Something in me said, “I’m not going.” It sounded like I was not being respectful, like I didn’t realize the enormousness of this gift that was given to me. I finally made my parents understand. I have always been aware of us as a people in this place, ever since I was three years old. So even though we had no reflections on TV, in magazines, on billboards, I knew that in school they were not telling me the truth: Dick and Jane are not the only children. Even having nothing to sustain you in the system, you knew that in fact your culture and community were valid.

My sight has been honed by ancestors and family long before me. I take responsibility for my life and experience in the here and now by forming an aesthetic I hope speaks to the seriousness of my message and hopefully my audience sees the irony, wit, and humor along with the cutting edges of my work.

People ask me, “What are the razor blades for,” or “What are the wrenches for?” They are for whatever you’ve felt, whatever you’ve seen. Then, how do you use it. Do you just take it all in and let it burn on you like acid, or do you take that very same thing and make something meaningful out of it. Do we talk about it—”there’s a hole over there you’re going to fall into.” Or do you act like you don’t see it and let your brothers and sisters fall in the hole? What do you do? It’s always on you. All of us have had these experiences, but do we ignore them, do we acknowledge them, do we act like they’re not there? A TV reporter asked me what I thought about Mandela being freed, and I am elated of course. But I also know that after the celebration people will recognize that they are killing more people now, like the 13 who were recently killed at a peaceful demonstration—the police shot into the crowd again.

Thompson: I recently heard a call-in show on public radio about the transition to a new government in South Africa. Callers, who were predominantly black, were very concerned that the new government was not going to be a true democracy; they were concerned about the communist rhetoric of the African National Congress. Then an Eastern European voice came on and said, “Why can’t you just let the people form their government and make whatever mistakes they have to make. They will be their mistakes. Who are you to question them about democracy?” Most people in this country, not just blacks, have never seen a true democracy.

Maynard: No, we haven’t. And to have the illusion that we are in a democracy is unbelievable. I tell little kids, communism, democracy, republican, democrat—you’re sitting home with your family eating and somebody bounds through your door and says you’re eating the wrong thing, or you’re dressed the wrong way…What do you think about doing that under the name of any credo to any human being? Forget all those words—they mean nothing to us. It’s one human being to another. What I said to the TV interviewer, in essence, was “Walk in a black South African’s shoes for 10 years—live, work, and raise a family under the same conditions. Then let’s sit down at the table. It’s the only way you will understand. You will have to experience it.”

Look at the land we’ve lost here in the Southern U.S., think of all the bogus deeds and promises given to us. Your grandfather and grandmother worked for years under the assumption that they owned something other than worthless paper. Look at all the lives that we’ve lost, look at how drugs have devastated our community from coast to coast. Look at our devastated educational system, and who we have teaching. Look at what basic rights should be, for every human being. Everyone needs the dignity of meaningful work. As you’re growing, you must feel that whatever you’re doing will be meaningful.

Thompson: But people want to be blind to it. I don’t think the middle class has yet realized how bad off we are, and they are.

Maynard: The system pits one group against the other, and you’re so busy thinking that it’s them, or those are the ones using my tax money on welfare. We know in fact there are more white people on welfare than black people. But we’re not taught to think, and we don’t read. TV remains the main source of information, good and bad.

Thompson: But on television, they always show “the black person on welfare.”

Maynard: TV has been the worst of weapons but also a blessing because people sitting in their kitchen will say “that kitchen doesn’t look like my kitchen!” Nobody is working on TV but they’re wearing silk dresses—and you don’t have one. Before TV, people in the community could be a little more satisfied because everybody was wearing more or less their own style. But when you were growing up you had your own imagination. I certainly had mine, and it was sacred. I made my pictures whenever I had time. These kids have been polluted, but even in that swamp flowers grow, with love and support.

Thompson: Can you comment on our constant change of identification: we go from Negro to colored to black to African- American. What significance does that have?

Maynard: Searching for identity, by those who have lost it. As I said, because we have no positive reflection of ourselves, we have been decimated, on purpose. But I really believe that until the ’60s we were still very intact about who we were.

Thompson: What do you think brought that about in the ’60s?

Maynard: Integration. Natural integration is something else: I go where I want to go. We needed access to health facilities, good housing, education, but I don’t think we needed to feel like our very lives depended on us going into a place where we don’t have enough money to spend anyway. Nobody thought of having political access along with it. Somebody asked me last week, “Don’t you feel there’s been any progress?” What does progress mean? Life progresses all by itself. We all came on this earth together. Do we have economic access to a decent place to live, food, hospitals? I don’t think so. Has anybody ever given someone freedom? How can you give me freedom? How can one human say to another, “Now you are free.” We know this, but will we own up to that which we know—or will we still pretend not to know? Every human being knows that you cannot ask for freedom. It comes with birth.

Thompson: What roles are black people playing in the arts at the end of the 20th century?

Maynard: From what I see we have been hoodwinked into thinking that this is a business, that this is a way of making a living. But we are a cultural voice of the people and we have to know that, acknowledge that. No matter what they are saying you are and what you should be doing, prior knowledge tells me and has always told me that I could never use art that way. I look at work that is technically wonderful and ask, “But do you have something to say?” I always think, if I am not graced with tomorrow, will I be doing something the day before or the moment before that I really meant? I don’t understand people buying art to put in a vault because it will bring them future equity instead of feeding their soul. People come to me and say they’ve been told they should buy some of my work, and I ask have you ever seen it? “Well, no.” Well do you want it as a commodity? You are going to take my breath! I want you to see it, I want everybody to see it. I tell everybody to bring their children to see it.