Vadis Turner Encounters

Share:

The night before I flew to Alabama, I went to opening night of Medea at the Metropolitan Opera. Typical characters—rich, high-powered Upper East Side couples, opera queens and their dates, and a smattering of minor celebrities (I spotted Gina Gershon)—milled about on the red-carpet and sipped champagne. It was a type of New York glitz that echoed past decades; apart from the plastic champagne flutes, it could have been in the 1970s.

I watched the myth of Medea unfold. She’s betrayed by her lover, who is marrying someone else. Banished from the citadel, the call to revenge grips her. Amid the brutality, what stood out to me was the relationship between Medea and her confidante, Neris. Their relationship spoke to the complicated dynamic that exists between those who have been cast out. Neris attempts to steer Medea from violence but ultimately fails, and at the end of the opera, Medea kills her two children. A high-camp video projection of flames swallows her and their little dead bodies.

The next morning, I was on a plane to Huntsville, AL, to view Encounters, a solo exhibition by Nashville-based sculptor and multimedia artist Vadis Turner, whom I met 10 years ago. In traveling to Alabama, I felt as if I were heading into the belly of the beast—the pinnacle of a culture that I am a part of, yet fail to fully understand, one of the dyed-red defenders of American violence, ticking back the years to a pre-Roe era. This is how the American South is generally regarded by those Americans who don’t live there—there’s often an impulse to distance, and to other.

Vadis Turner, Rose Window, 2021, curtains, bedding, ribbon, steel, thread. resin, acrylic paint and mixed media, sound component composed by Emery Dobyns, 84 x 80 x 18 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Vadis Turner, Primrose Path Engulfed in Smoke, 2011, ribbon, clothing, antique textiles, and mixed media, 68 x 63 x 5 inches [photo: Vadis Turner; Courtesy of the artist, Geary, Millerton, NY, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

To consider New York and Los Angeles the sole American cultural centers is cliché. But making a case for Alabama is tricky—it doesn’t have the institutionalized exoticism of Marfa, TX, for example—which is precisely why it’s a good place from which to ask the raw and simple question: Does contemporary art have the power to start dialogue and effect change?

Encounters features sculptural works by Vadis Turner, created between 2011 and 2022. Domestic materials have been woven, bent, and constructed into free-standing sculptures, reliefs, and smaller works displayed on plinths. The palette of the exhibition is ashy and dark, with streaks of bloody red and copper hues, all lit by a glowing pink light at the rear of the room.

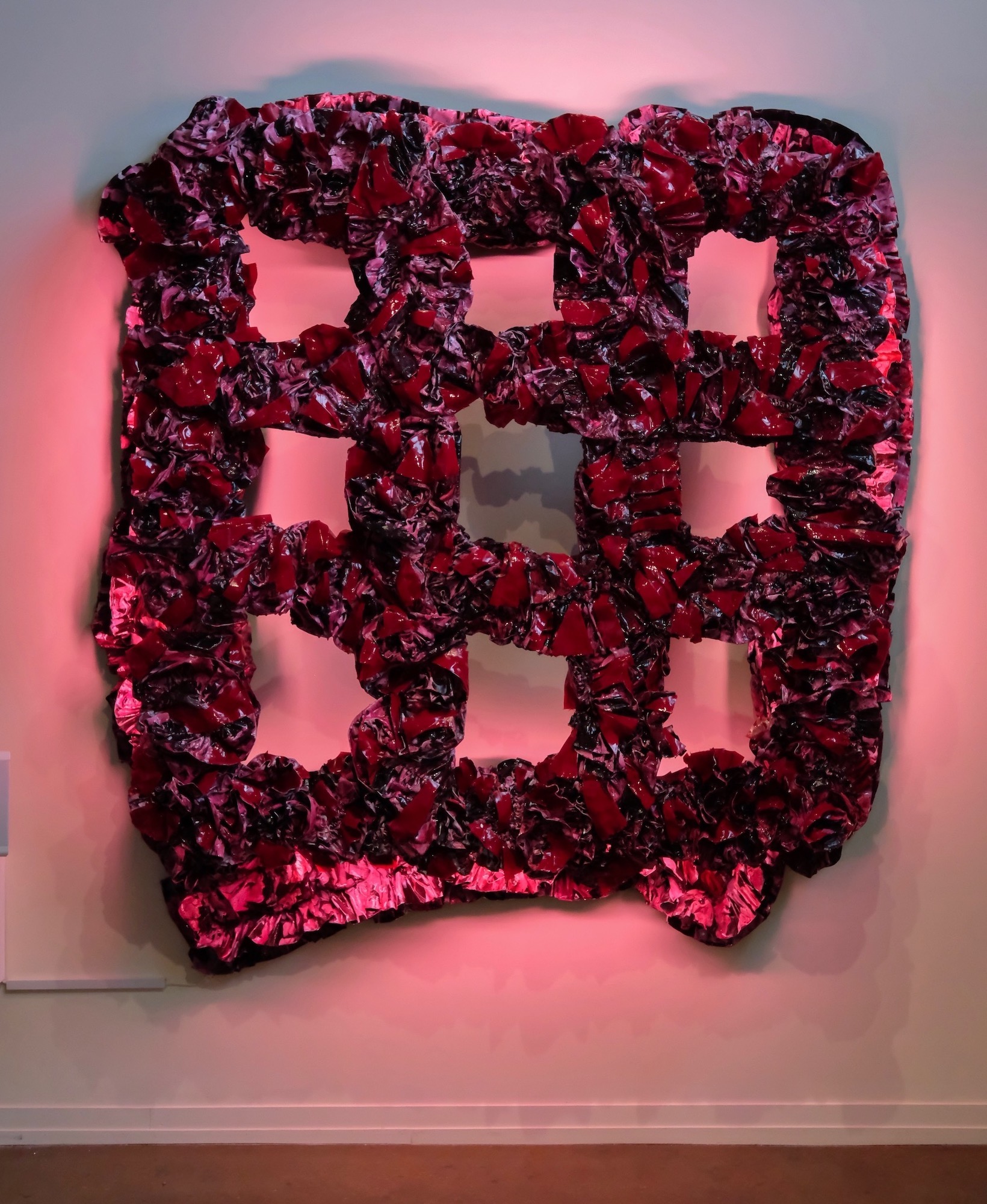

Vadis Turner, Red Gate, 2018, braided bedsheets, dye, acrylic, resin, wood, mixed media, 118 x 120 x 10 inches [photo: John Schweikert; Courtesy of the artist, Geary, Millerton, NY, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

There’s a beautiful progression of the artist’s materials evident in the exhibition’s chronology, beginning with Primrose Path Engulfed in Smoke (2011), a relief of stormy grays and green ribbons that—via slippery satin—conveys ecological motion, a lush and decadent chaos. Later relief works are less painting adjacent. Red Gate (2018) is a particularly powerful, saturated monolith of woven bedsheets and charred wood. The form and construction recall something vaguely ancient, and violent. The sculptural materials in Encounters are not just of the domestic, they are bound to it, which makes sense, as the artist lives and works in her grandparents’ Nashville home. She mines materials from the passed-down family home, such as old curtains and linens, and incorporates them into her work. Lineage and the attempt to wrench away from one’s past, despite being tied to it, are materially and emotionally present.

The past is also tangible in Turner’s less biographical materials, such as the thrifted bed sheets used to create the sculptures Red Gate and The Trophy (2019), which speak to an agency of materials that the artist focuses upon interrogating. There’s a consideration of expectations—of materials and objects—that recalls the long-standing tradition of such artists as Eva Hesse, with her use of industrial rubbers. Her materials are always already touched, whether by people, use, or the symbolic weight they bear. Turner’s gate form is oppositional, whereas sheets are inviting. This discord posits something sinister—those bedsheets used for sleeping, for fucking, could have also borne a rape. The artist’s hand twists us away from the signifiers—the ripping and weaving of bed sheets, the wood she sets on fire. These gestures represent an aliveness even more powerful than the material, and the art becomes a record of the artist herself.

Turner sticks to traditional forms—the relief, the vessel, the grid—that prompt feelings of being tethered, whether to art history, to histories of women being yoked to the domestic, or to gender altogether. The artist’s vessels address these tethers elegantly. She became interested in vessels made from fabric, a form and a material meant to hold, but such vessels are porous, some with gaping holes—a refusal. Messy Vessel, The Crazy Lady (2021), an encrusted, open vessel conjures motion as one imagines water pouring right through it.

Loose Leather Grid and Cement Grid (2020) features a cement adhered to the wall and a thin red fabric lattice that appears to be clinging onto the cement form and slipping off it simultaneously. The expressive possibilities of the grid become figural. The fabric grid looks like a tattered flag, a loose replica of the sturdier structure on the wall, a shadow, something spat out and unraveling. The fabric grid has more squares, as if its spaces have multiplied from the original.

The Witch (2019), a charred, burnt vessel (also made from thrifted bedsheets and charred wood) recalls scores of persecuted women. We must consider the incredible force that goes into maintaining the gender status quo. If there were something so essential about binary gender, there wouldn’t need to be the constant threat of violence to ensure its survival—the recent series of laws targeting trans youth, right wing anti-abortion laws, enforcers inside the home, etc. (One disturbing consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic was a forced domesticity, and domestic violence cases shot up dramatically.)

Vadis Turner, The Witch, 2019, bedsheets, charred wood, acrylic paint, resin and mixed media

26 x 24 x 16 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Andrea and Scott Zieher, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

But still, I question the centering of “women’s work” in 2022, which reads like a throwback to the 1970s. It’s sticky. If womanhood is so oppressive and enforced, couldn’t art be the space in which to just say fuck it, to reject it entirely? What bits of the woman-identifying experience should we drop or carry forward? Or is art the vehicle we must enter to lift out of oppression, to see it clearly, and move on?

But one can’t regard gender without considering race.

I think of the ruffles and curtains of Southern cotillion culture—the prettiness stitched to shroud white supremacy; the way scalloped porches of plantation houses look like icing on a cake. I think of Gone with the Wind, and of monuments to the Lost Cause myth. Drawn Curtain (2021) has an effect similar to that of the vessels. It’s meant to be closed, but it’s gaping open. Drawn Curtain and Weighted Window (both 2021) are created, in part, from curtains that the artist found at her grandmother’s house. I think about the thinness between the outside and the inside, the shades of transparency and opacity. What the curtain hides and the hierarchies of oppression. Who gets to draw the curtains to not see what’s going on in the field beyond? And who gets to make a gown out of them?

Vadis Turner, Drawn Curtain, 2021, curtains, gravel, copper leaf, acrylic, resin and steel, 124 x 96 x 6 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Vadis Turner, Weighted Window, 2021, curtains, gravel, copper leaf, acrylic, resin and steel, 132 x 90 x 5 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Windows and concealment are major themes in the exhibition. Weighted Window, a glowing grid constructed from red-painted—even gore inspired—curtains, bedding, steel, thread, ribbon, and copper leaf is backlit with pink. When you approach, it hisses. There’s a theme park quality to the light and noise, like a Natural History Museum diorama of abstract sculpture. These elements attempt to animate the works, the artist points out a type of stagnancy. There is more motion in the works without these elements, but I love the nod to the horror genre, even with its camp qualities, where objects hiss, and windows are coated in blood. There’s a claustrophobic feeling, like when the girl in the horror film realizes the call is coming from inside the house, which is then followed by two other thoughts: that she must get out of the house immediately, and that she’s stuck—which leads me to the myth of Circe and Scylla that Turner represents in two sculptures: Window Figure, Circe (2021) and Window Figure, Scylla (2022).

Vadis Turner, Loose Leather Grid and Cement Grid, 2020, leather, cement, wood, thread and mixed media 72 x 60 x 9 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Geary, Millerton, NY, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Trapped in an eternity of suffering, Scylla is a six-headed reptilian monster composed of different elements—woman, dog, and sea. According to Homer, she’s said to have the voice of a puppy. Scylla was a beautiful nymph whom Glaucus, the prophetic Greek sea god, took sexual interest in. Glaucus asked Circe, goddess of sorcery, transmutation, and necromancy, to make Scylla love him. The request backfired because Circe loved Glaucus. So, instead of casting the spell for him, she turned the once-beautiful Scylla into a monster who would eventually be slain by Hercules.

Vadis Turner, Window Figure, Scylla, 2022, curtains, gravel, resin, acrylic and steel, 78 x 112 x 30 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

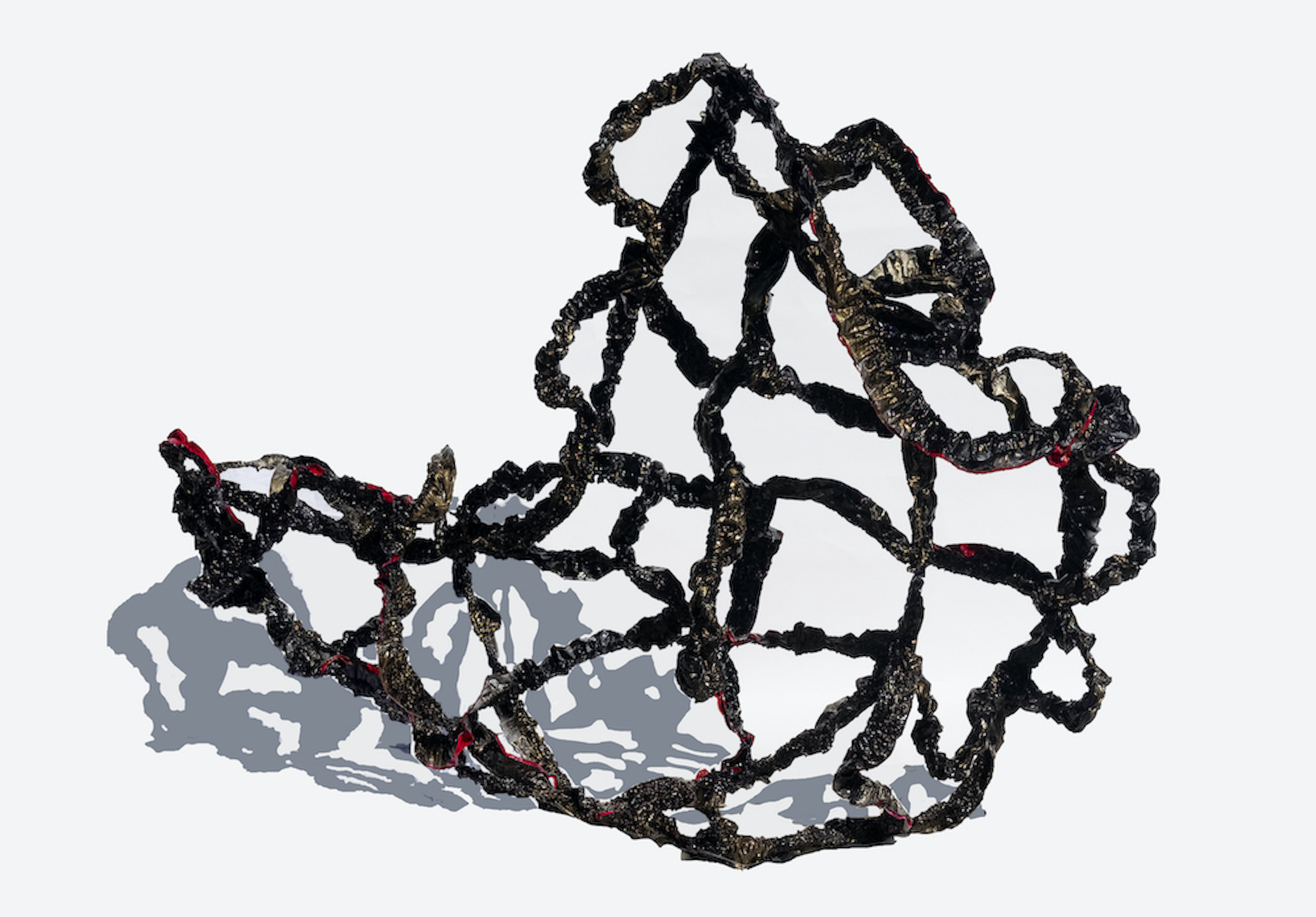

Window Figure, Circe has a crackling sound element, which binds the space between the two mythological figures. Window Figure, Circe and Window Figure, Scylla seem to gesture to each other in pain, with ambient sounds of fire between them. The grid, a symbol of order, is collapsed and coming undone. The finish on Window Figure, Scylla looks like charred, wounded skin with exposed bits of flesh and blood. The myth of Circe and Scylla resembles that of Medusa, a woman who, in some versions of the myth, was raped, then punished and transformed into a monster by the goddess Athena. The figure that stands out to me, alongside Medea, Circe, and Athena, is the plantation owners’ wife—which could be correlated to the position of white women in America now regarding one’s oppression and one’s ability to oppress. The power (and even evil) that is explored in Turner’s work is double-edged, which is vital when considering how power operates, how we are bound up to it, how it exists within and outside us. The thing about all these women is that their response to their own injury is to destroy others.

Winged Victory Vessel, a gnarled, burnt sculpture with the shape of wings, bears the title of a female figure who has been used for masculinist and nationalist purposes in sculptures. The artist erodes this symbol. I think of toppling monuments, tearing down the symbols of the past, lighting them on fire, and letting them rot. I think of the Winged Victory figure in the monument to Sherman in Central Park, and the tethers between the South and the North. If one views the Winged Victory Vessel from a different angle, her angel wings appear to be devil horns—as if she could be swallowed up in crackling flames, just like Medea.

Vadis Turner Window Figure, Circe, 2021, curtains, copper, gravel, resin, acrylic and steel, sound component composed by Emery Dobyns, 92 x 64 x 45 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Vadis Turner, Winged Victory Vessel, 2021 charred wood, ribbon, resin, 24 x 19 x 16 inches [photo: Hannah Deits; Courtesy of the artist, Geary, Millerton, NY, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL]

Jillian McManemin is a writer, artist, and Founder of the Toppled Monuments Archive. She has written for Hyperallergic, ART PAPERS, The Broadcast, The Brooklyn Rail, BOMB, art agenda, Metrograph Editions, among other publications including forthcoming pieces with Texte zur Kunst. In 2022 she was Shortlisted for the Creative Capital Award and in 2018 was awarded the AICA-USA Art Writing Fellowship. She is currently working on her first book, Sculpture Kills, autotheory that centers around fatal works of contemporary art.