Vacant Presence

Jesse Darling, Support Level, installation view, 2018 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of Artist and Chapter NY, NY]

Share:

In the summer of 2018, debate escalated in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere over legislative bans to end the use of plastic straws by food service establishments. In these discussions, people concerned about the environmental impact of plastic straw usage, or about their right to use something as simple as a straw, were thrust into debate with disabled people who use straws as accessibility prostheses for basic nutritional intake. In these debates, the latter group was made to illuminate this largely unconsidered aspect of the issue, and to defend its right to access the object in question. To convincingly make these arguments, disabled and sick individuals had to render the fact of their disability or illness legible, their care and needs worthwhile. On trial was not the prosthesis itself, as its opponents claim, but its user. The disabled body was front and center. In the work of artists Park McArthur, Jesse Darling, and Julia Phillips, the presentation of these prosthetic devices divorced from their users helps mitigate the vulnerability that can accompany visibility while still alluding to the body, whether sick, hurt, or disabled, through traces of its presence.

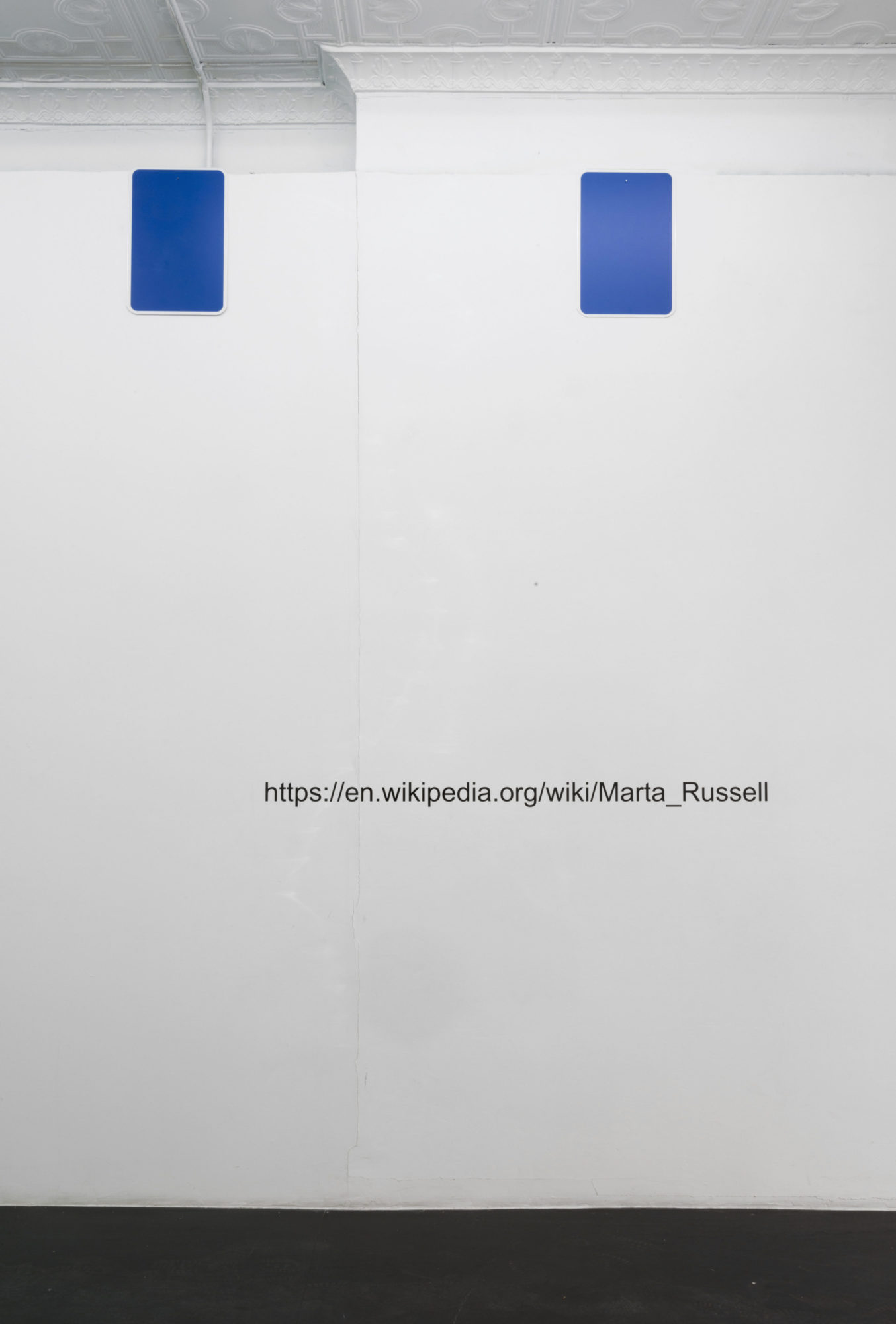

Four years before this debate erupted, an installation by Park McArthur filled a small gallery, Essex Street, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, with 20 ramps. The structures—ranging from little chunks of splintered plywood to the kind of industrial steel rectangles that unfurl, tongue-like, from city buses—were themselves as heterogeneous as the many different bodies they were designed to assist. McArthur sourced the planks in Ramps from institutions she’d worked with in the past, many of which had built or acquired the structures specifically for the artist’s accessibility needs. The Tetris-like installation conjured the body: how it moves, how it’s moved, what it needs. This evocation was accomplished without depicting the body, disabled or otherwise—even the signs that dotted the walls, the familiar International Symbol of Access (a white icon of a person in a wheelchair against a blue background), were scrubbed of the figure, leaving behind only blue rectangles. And, as McArthur points out in an interview with Jennifer Burris, the documentation of the exhibition that circulated most heavily after its 2014 installation at Essex Street was taken from an aerial perspective, a disembodied viewpoint that one can experience only by using mechanical prostheses.1

Park McArthur, Ramps, installation view, 2014, [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street, New York]

Jesse Darling, Eccentric Contraction (still standing), 2017, steel, aluminum, rubber and lacquer, 92 × 30 × 38 inches [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist and Chapter NY, NY]

The sculptural material is therefore twice removed from the body, which is absent from the space representationally and can enter or view the space only in specific, limited ways. As in the straw debates, the focus is on the material supports divorced from the bodies who rely on them. Focus is instead placed on the material qualities of the prostheses under consideration, rather than (exclusively) their users. We see that some ramps look sturdy and capable, whereas others—tiny, uneven, falling apart—are in disrepair. These shortcomings are revealed to unfold on the level of material and the institution, rather than that of the disabled body. What is to be done with objects intended to ease mobility that do not, in fact, fully accommodate? The ramps’ installation—with planks gathered together in every direction, one cutting off access to another, leading seemingly from nowhere to nowhere—further abstracts the notion of what actually constitutes support. Is institutional support accomplished by acquiring and installing a ramp, or must it go further than Americans with Disabilities Act compliance? McArthur puts pressure on a purely architectural understanding of support, one that gets disabled people past the threshold, but pays little mind to the social and structural barriers to entry that might prevent them from arriving in the first place, or from being seen, heard, or cared for once they’re inside—a critique advanced by disability rights activist Marta Russell, whose book Beyond Ramps McArthur references through a Wikipedia link adhered to the gallery walls.

McArthur, in Ramps and elsewhere, articulates an aesthetic of nonaccommodation, one in which the conjured-but-absent human body is not just lurking outside the frame but also somehow animates these prostheses as quasisentient objects.2 A similar operation was at work in Jesse Darling’s exhibition Support Level at Chapter NY in early 2018. Darling’s sculptures reference the visual and material fields of hospitals and waiting rooms, as well as that of disability—incorporating such elements as the “back brace, mild steel, lacquer, grip bar, cool pack.”3

Jesse Darling, Collapsed Crane, 2017, steel, aluminum, rubber and lacquer, 30 × 24 × 13 inches [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist and Chapter NY, NY]

The press release for Support Level states that Darling “draws from the clinical as a structural and social form of abjection.”4 Julia Kristeva writes of the abject not just as a site of disgust and degradation, but as that which must be forcibly cast off, a literal marginalization: “the place where I am not.”5 However, one of the triumphs of Darling’s sculptural practice is the careful articulation of a critical stance toward our existing systems of care alongside the resistance to abjection as illness and/or disability’s primary—or sole—affect. Darling’s sculptures resist Kristeva’s sharp subject-object distinction as they float above the gallery floor and snake up its walls. There is a levity to Darling’s treatment of materials: Crawling Cane, a steel cane bent into the shape of a rollercoaster drop, arches over the gallery floor; Comfort Station (both works 2017), a commode chair on warped, spindly legs, appears moments away from falling onto its side. The objects of support themselves appear unsupported, and they seem to speak to one another in a language indecipherable to us. As with McArthur’s Ramps, Darling’s is an animated sculptural space. From the bent rubber-coated adjustable steel cane to the wall-mounted assistance bar that choreographs a body’s interaction with the space it inhabits, Darling’s works are almost creaturelike in their playfulness. They crouch and puddle.

If Darling’s work maps a space of abjection, this abjection is not—or not solely—that of sickness or disability but (as in McArthur’s practice) that of the medical-industrial complex and its one-size-fits-all approach to the specificities of the body. Darling’s modifications to the sterile stuff of doctors’ offices propose a resistance to this depersonalization. The anthropomorphic qualities of the sculptures make room for what bodily representation of what illness looks and feels like absent the human body itself.

The works in the Julia Phillips solo exhibition Failure Detection at MoMA PS1, as with McArthur and Darling, evoked a bodily vacant presence. Phillips’ installations were, for the most part, devoid of human bodies, but full of their imprints and traces. Like their work, too, Phillips’ sculptures reference the realm of the medical-industrial complex, but unlike the sanitized, standardized contemporary hospital room materials Darling uses, or the ad hoc outdoor materiality of McArthur’s ramps, Phillips mines the connotative fields of eugenics, slavery, human experimentation, and psychiatric hospitals. Phillips’ work is disciplinary in tone and material: although there are dildos and harnesses throughout, even they evoke circumcision or castration more so than rough pleasure. In confronting Phillips’ sculptures, onlookers are made aware of their bodies, made to wonder how, exactly, a body might fit here, use an object, or be used by it.

Jesse Darling, Comfort Station, 2017, steel, aluminum, rubber and lacquer, 31 × 55 × 33 inches [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist and Chapter NY, NY]

With such titles as Tuner, Protector, Observer, and Intruder, Phillips’ sculptures clearly bracket space for the presence of active human bodies, indicating where they have moved or might move in the future. In Fixator (#2) (2017), an upright metal frame reaching slightly less than six feet above a shower-tile flooring is bisected by a chastity-belt-like groin cover. The cover, complete with thigh straps and a hooded appendage, implies space for a penis; the sculpture is topped with a chinrest like the kind you might place your face into during an eye doctor’s exam. In contrast with the readymades that constitute Ramps and Support Level, Phillips’ work is not explicitly appropriated from a context of use. And yet, these sculptures function not merely as menacing, nightmarish art objects but also as traces of lived violence that Phillips has made literal with footprints and handprints left in ceramic glaze on the installation’s wall and floor tiles. It’s instructive to consider Phillips’ sculptures in conversation with those of McArthur and Darling to understand how Phillips is creating a new material and psychological field of inquiry, as well as making clear the ways in which the systems of social and medical support deemed outdated still haunt the present.

A 2016 essay, “The Guild of the Brave Poor Things,” co-authored by Park McArthur and Constantina Zavitsanos, maps the centuries-long tradition of disabled people being “held and exhibited as objects in court”—disability as performance. In the face of this coerced visibility, the authors continue, “I want to get too close to see, so close you gotta feel through someone elsewhere or somewhere elseone as never one.”6 Park McArthur, Jesse Darling, and Julia Phillips offer a care-full material and conceptual relationship to representation that engenders a more expansive understanding of how a body may be pictured, conjured, understood without needing to be literally imaged. In these sculptural fields—assembled, trodden on, and used by humans but absent the bodies themselves—we can feel through someone elsewhere, aware of the particularities of our own embodiment. The bodies that have been forcefully put on display—as spectacles, on the auction block, in the crosshairs of contemporary surveillance tools—are here given respite. The disabled, ill, gendered, racialized subjects that use these prostheses as a matter of course become too close to see. The structures are made visible as the subjects of inquiry, rather than as the props they were designed to be. We’re then able to see them through feeling, to feel them through seeing.

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.

Heather Holmes is a writer and editor whose work concerns the specificities of the body and the built environment.

References

| ↑1 | “Park McArthur by Jennifer Burris,” BOMB, February 19, 2014, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/park-mcarthur |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The idea of nonaccommodation is taken from Sara Ahmed, who writes, “We learn about worlds when they do not accommodate us.” Sara Ahmed, “An Affinity of Hammers,” Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, eds. Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 221–234. |

| ↑3 | Materials listed for Jesse Darling’s sculpture Plexus, 2017, 28 3/4 x 19 5/8 x 7 7/8 inches. See http://chapter-ny.com/exhibitions/past/jesse-darling |

| ↑4 | Chapter NY, “Jesse Darling: Support Level” (press release), at http://chapter-ny.com/exhibitions/past/jesse-darling |

| ↑5 | Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982). |

| ↑6 | Park McArthur and Constantina Zavitsanos, “The Guild of the Brave Poor Things” in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, 235–254. |