How To Make an Old World New?

Notes on the Whales in the Room

Wu Tsang, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, Titilayo Adebayo film still, 2022 [Photo by Greg Amgwerd; courtesy of the artist and Schauspielhaus Zürich]

Share:

I. Mocha Dick

In August 1819, more than a century after a Nantucket whaleman caught a sperm whale for the first time off Nantucket’s coast, the Essex departed the island for the Pacific. Whales in the Atlantic had all but disappeared following the industrialization of the hunt, as ships transformed into floating factories1 tasked with extracting the whale oil coveted for “powering, lubricating, and illuminating the first phases of the industrial revolution.”2 Upon arriving at Cape Horn, however, the Essex found no prey, so the vessel continued into the South Pacific’s open waters, where it encountered a whale pod on November 20, 1820. As the crew transferred to their whaling boats, a massive bull whale rammed—and sank—the main vessel. “Anything but chance … directed his operations,” concluded chief mate Owen Chase.3 The event became an inspiration for Herman Melville’s 1851 novel, Moby-Dick.

Another vengeful sperm whale said to have inspired Moby-Dick was Mocha Dick, a white bull named after the island where it was first seen, which artist Tristin Lowe monumentalized in Mocha Dick (2009), a 52–foot-long vinyl inflatable coated in white industrial felt. “Numerous boats are known to have been shattered by his immense flukes, or ground to pieces in the crush of his powerful jaws,” wrote seafarer J.N. Reynolds in 1839, describing ships armed “for the destruction of [Dick’s] race,” and captains who saw Mocha Dick as a career-defining kill.4 Mocha Dick’s capture, records Reynolds, yielded 100 barrels of oil and a “proportionate quantity” of spermaceti, coveted to create odorless, luminous, long-lasting candles that signified, per scholar Emily Irwin, “the height of candle-making technology for Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries.”5

At its core, “the whale hunt was primarily a quest for light,” says academic Bob Johnson, and “the whaling industry was at bottom an energy industry.”6 Although all parts of the whale had uses, it was whale oil that lubricated machinery and lit public spaces, factory floors, lighthouses, and private homes throughout Europe and the United States. By 1780, London streetlamps burned the oil of some 500 sperm whales annually,7 paving the way for a 24/7 industrial culture that Jonathan Crary described as the end of sleep. “Derived from a living organism, rather than fossilized or ‘mineral’ sources,” writes historian Bathsheba Demuth, “whale oil was … an organic form of energy … imbedded in the economies and technologies of early industrialization,”8 which, in turn, powered European and American colonial power and its culture of capitalist extraction. As David Haines notes in Maritime History as Global History, whaling voyages “expanded European and American understanding of the geography, resources and cultures of the world’s remote oceans, while at the same time exposing those cultures to the ‘light’ of European expansion and global capitalism.”9

Wu Tsang, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale film still, 2022 [photo: Greg Amgwerd; courtesy of the artist and Schauspielhaus Zürich]

John Huston, Moby Dick, 1956, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube]

Entwined with the whaling industry, then, which peaked in the mid-19th century, was the violence of a colonial modernity that rendered the world open for the taking. As writer Tom Kizzia reports, the whale boom was catastrophic for the Iñupiat of the Alaskan Arctic, as Yankee whalers decimated bowhead populations north of the Bering Strait.10 Around the same period, whalers began describing grey whales as devil fish based on the ferocity of their retaliation, particularly when defending their young, as they were driven to the brink of extinction amid a Baja whale rush.11

“At the end of the day,” says Ric Burns, director of the 2010 documentary Into the Deep: America, Whaling & the World, 19th-century whaling was “an extraordinarily primal, existential confrontation between human beings and what was really the last frontier of untamed nature, the oceans of the world.”12 Hence, Reynolds’ description of the “intrepidity, skill, and fortitude” of the whalers, which he called “the natural result of the ardor of a free people; of a spirit of fearless independence, generated by free institutions.” That freedom—above all others and above all else—was encapsulated by the crew motto in Moby-Dick: “A dead whale or a stove boat,” which expresses a political ideology akin to liberty or death.13

With that zero-sum confrontation in mind, it’s not hard to see the actions of whales like Mocha Dick as anti-capitalist and anti-colonial forms of resistance to the brutal occupation of the seas by industrial capitalism’s human foot soldiers. And within that context, it is not outlandish to see Captain Ahab, Moby Dick’s adversary hell-bent on exacting revenge on the whale that cost him his leg, as the whale’s inverted mirror. Both are products of this “first mass market in cheap light … built on a widespread cultural tolerance for the exploitation of both people and nature.”14

Melville’s novel reflects that mirroring. One chapter on Ahab’s obsession with Moby Dick as the “monomaniac incarnation of all those malicious agencies which some deep men feel eating in them, till they are left living on with half a heart and half a lung,” is followed by a meditation on Moby Dick’s “appalling” whiteness. Acknowledging associations of whiteness with privilege, in which “various nations have in some way recognised a certain royal pre-eminence,” Melville describes “an elusive something” lurking “in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood.”15

That “something” is the real and symbolic whale in colonial modernity’s room: a reflection of an extractive culture shaped by the violence of systemic capitalist accumulation and production that naturally produces fearsome blowback by those who have been classified as grist for its bloody mill. After all, if Ahab could desire vengeance for what he lost in the service of capitalism, why would a whale not react against the slaughter of its kind for the same reason?

IIa. (Anti?) Social(ist) Lea(r)nings

In 2021, a study found that the strike rate of whaler harpoons on sperm whales in the North Pacific during the 19th century fell by 58% over a few years, leading to the conclusion that whales were sharing information and making “vital changes to their behaviour.”16 “It is not hard to imagine that they understood what was happening to them,” concluded author and curator Philip Hoare. Melville observes that awareness in Moby-Dick, too. Apart from sharing stories of other fighting whales, he describes sperm whales appearing in larger herds, “sometimes embracing so great a multitude, that it would almost seem as if numerous nations of them had sworn solemn league and covenant for mutual assistance and protection.”17

A more recent example of collective action is of orcas attacking boats off the coasts of Europe and North Africa. (A 2022 study counted some 500 encounters since 2020.) One theory names White Gladis, an orca avenging their traumatization by a vessel or fishing net, as the originator of the movement—her own calf was among the 11 juveniles attacking boats off the Iberian coast in 2023, in a trend that has appeared to spread through social learning.

Ayman Zedani’s artwork Between Desert Seas (2021) presents a historical case study of that learning with a salt mound surrounded by audio speakers emitting sounds of Arabian Sea humpback whales and interviews with conservationists. The only nonmigratory humpback population in the world, Arabian Sea humpbacks separated from humpbacks of the Indian Ocean about 70,000 years ago. As a consequence, they developed their own unique culture, including language and songs that continue to evolve independently of other humpbacks, whose songs have been found to change according to interactions with different groups, and, in some cases, other species.18 “Such knowledge passed down through kin lines is the mark of culture,” writes Demuth on the case of Bering Sea bowheads.19 That transfer has been shown to include memory and association in nonhuman life. As one 2010 study found, crows caught by mask-wearing researchers would react to anyone wearing those same masks later.20 A study that followed discovered crows passing on experiences—and learnings—to other crows.21

Ayman Zedani, Between Desert Seas, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of the artist and Diriyah Biennale, Diriyah]

“I definitely think orcas are capable of complex emotions like revenge,” said Orca Behavior Institute director Monika Wieland Shields on NPR in June 2023. That summer, reports of dolphins attacking swimmers in Japan raised speculation that they were retaliating against the annual Taiji dolphin hunt. An aerial survey of New England waters that counted orcas, fin whales, minke whales, humpbacks, and dolphins set Twitter alight with thoughts of an ocean revolution. Then, in autumn, resurfaced footage made the rounds via online tabloids. It showed elephants chasing two men who had killed a related elephant in Namibia, recalling studies suggesting that elephants attacking humans in Africa and Asia suffered PTSD from becoming orphaned or witnessing the poaching-related deaths of their families.

Whether nonhumans can understand what is happening to them—and, as such, can act in response—is an old question. Theories against nonhuman sentience have long justified human practices, but occasionally research has led to their reversal, as in 2018, when Switzerland banned boiling lobsters alive. Years earlier, in his 2004 Gourmet report on a mass boiling at the Maine Lobster Festival, David Foster Wallace concluded that “after all the abstract intellection,” it’s not difficult to observe a lobster’s preference, when in hot water, to live.22 Wallace’s rumination on the proximity to the act of killing—people boil lobsters alive in their own homes, he pointed out—recalls historian Lissa Wadewitz’s description of the American whaling industry’s “striking violence” and “the sheer volume of animal blood shed over the course of the 1800s.”23 Whalers dismembered cetaceans on the same ship where they lived. In one 1858 account, William Abbe described waking and dreaming in blubber.24

IIb. The Ship

Wu Tsang’s 2022 feature-length film, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, leans into the extreme intimacy of the whaling ship, first by depicting Pequod shipmates arms-deep in spermaceti, and then by amplifying the queer love story in Melville’s text between the novel’s American narrator, Ishmael, and his shipmate Queequeg, a South Sea Islander prince who ran away from his kingdom. With a script written by Sophia Al-Maria and narrated by Fred Moten, the story expands upon this intimacy by drawing on Trinidadian intellectual C.L.R. James’ 1953 reading of Melville’s novel, Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, which unpacks Melville’s vision of an emergent world system of globalized industrial capitalism contained within the microcosm of the Pequod.

Wu Tsang, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, Titilayo Adebayo film still, 2022 [Photo by Greg Amgwerd; courtesy of the artist and Schauspielhaus Zürich]

Tsang’s MOBY DICK reflects James’ reading of the mixed-race and mixed-class whaling crews of Melville’s time, where the common goal to profit from the collective kill, per an agreed distribution of spoils, was both a signifier and equalizer of difference. At the helm of that difference was Ahab, described by James as “the totalitarian type,” who is isolated from his motley crew—the enslaved, the colonized, the laborers—and enabled by his New Englander officers. Having forfeited his leg in service of a system that renders him and his workers, like Moby Dick, expendable, Ahab’s thirst for vengeance—which makes his crew expendable to him—parallels the whale’s desire for justice but fails to match the animal’s pursuit of collective reckoning. While Ahab abandons the goal of market profits—“the unchallenged foundations of American civilization in 1851”—and “sets up instead his own feelings as a human being,” he remains driven by personal interest.25

Melville describes Ahab, in a line that Moten quotes in Tsang’s MOBY DICK, as “a vacated thing, a formless somnambulistic being, a ray of living light, to be sure, but without an object to colour and therefore a blankness in itself.” James locates Ahab’s blankness in “the plan,” which connects the Hitlers and Stalins of the world, who nationalized state economies by building factories and power stations, removing mountains, establishing concentration camps, and wasting human and material resources on an unprecedented scale.26 “Their primary aim is not war. It is not dictatorship,” writes James, in lines that Moten also quotes: “It is the Plan.” Ahab, too, has a plan, which serves “no human purpose but merely the abstract purpose itself,” writes James, circling back to the system of capitalist production reflected on the Pequod and the white whale representing that system’s crimes and effects.

Wu Tsang, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, Tosh Basco film still, 2022 [Photo by Greg Amgwerd; courtesy of the artist and Schauspielhaus Zürich]

In between it all is the Pequod crew, whom Melville describes as “renegades and castaways” with “high qualities” and “tragic graces,” who become another kind of whale in the room. These are “the ordinary people of the world,” James summarizes, who aren’t absorbed by Ahab’s plan so much as they are thrown into it, leaving them with nothing but their solidarity to survive. Hence, the phrase Moten utters in MOBY DICK: “No more you, no more me, all we,” and opening scenes of life-affirming intimacy between Ishmael and Queequeg, whom Ishmael describes in Melville’s text as harboring “no civilized hypocrisies” in a world where “Christian kindness has proved but hollow courtesy.” As James notes, “In his nobility of spirit, his relation to Nature, his relation to other beings, and his philosophical attitude to the world, Queequeg was merely a member of the anonymous crew.”27 Anonymous because, on the ship, they all lived as one.

III. “Disputa de l’Ase” (or: The Whale)

What emerges in Melville’s microcosm of colonial modernity—a systemic capitalization of the world that has evolved into what Arif Dirlik described as the global modernity of the present—“is the intimate, the close, the logical relation of the madness, to what the world has hitherto accepted as sane,” writes James.28 Ahab’s crew lives in relation to this insanity and falls victim to it, as the Pequod is destroyed and, as Melville writes, “the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.”

Amplifying nature’s power over any pathetic human endeavor, Melville’s description of the Pequod’s demise recalls professors Anthony D’Amato and Sudhir K. Chopra on the whale’s right to life. Referring to Descartes’ assertion that animals can’t think because they cannot communicate their thoughts to humans, Chopra and D’Amato point out that whales evolved their brains 30 million years ago, 29 million years before the development of the present human brain. (Sperm whales, in fact, have the largest brains on the planet.) “Why should whales have evolved with a capacity to communicate their ideas to homo sapiens when the latter appeared only at the very end of the 30 million years of the whale’s history?” they ask. “Our failure to converse with whales could well be a matter more of our own limitation than of theirs.”29

Returning to Wallace’s reflections on lobster sentience, the question becomes the point. “Isn’t being extra aware and attentive and thoughtful about one’s food and its overall context part of what distinguishes a real gourmet?” Wallace writes. “Or is all the gourmet’s extra attention and sensibility just supposed to be aesthetic …?”30 Demuth locates that query in the 19th-century story of the Citizen, whose shipwrecked crew was sheltered by Indigenous hunters in the Chukotka region along the Siberian coast. “A whale for the men on the Citizen”—“whose ‘rituals of slaughter and profit’ are a study in the expectations of a growing market”31—“had no soul or country,” writes Demuth; whereas for the Iñupiat, Yupik, and Chukchi, whales were “a gift assuring human survival in its death, a means to power, a site of communal labor, a set of expectations and ceremonies, a theory of history.” Although “each made [a] living from the death of whales,” Demuth notes, “the difference was in how they answered more elemental questions. What is a person? What is a whale? What is a whale’s value?”

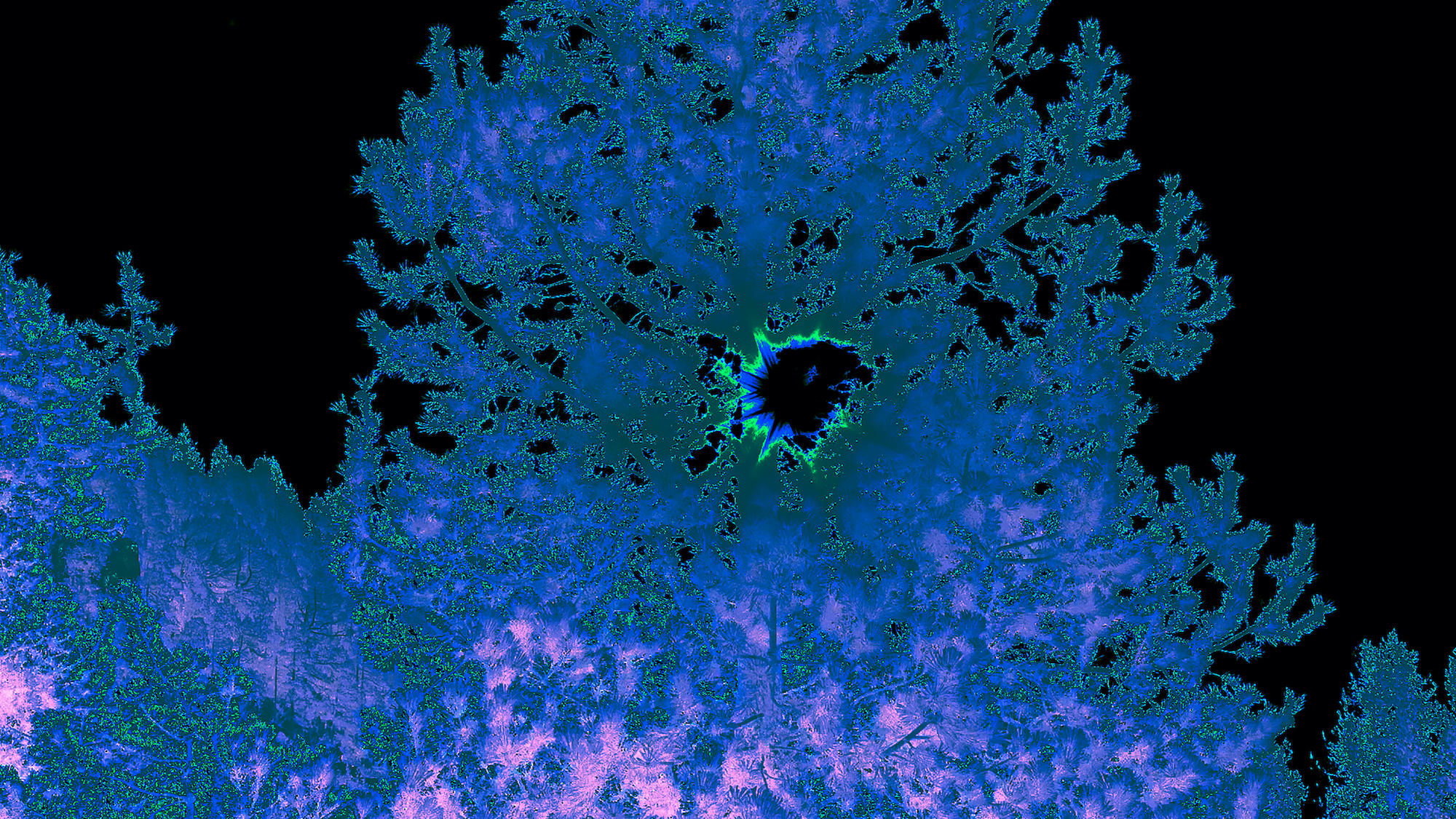

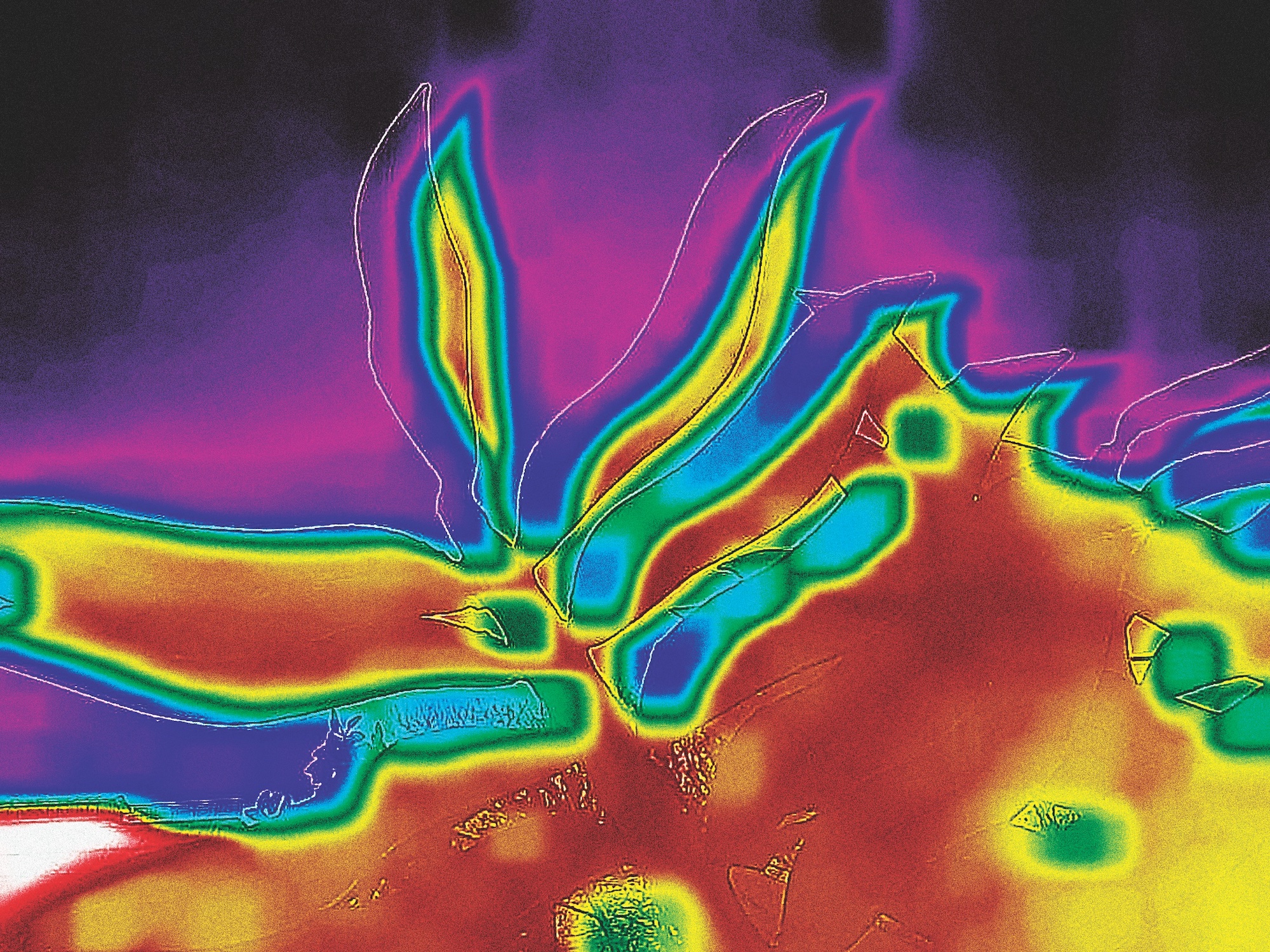

Carlos Casas, Bestiari (Batvision), 2024, audiovisual film, [courtesy of the artist © Carlos Casas and Venice Biennale]

Carlos Casas, Bestiari (Snakevision), 2024, audiovisual film, [courtesy of the artist © Carlos Casas and Venice Biennale]

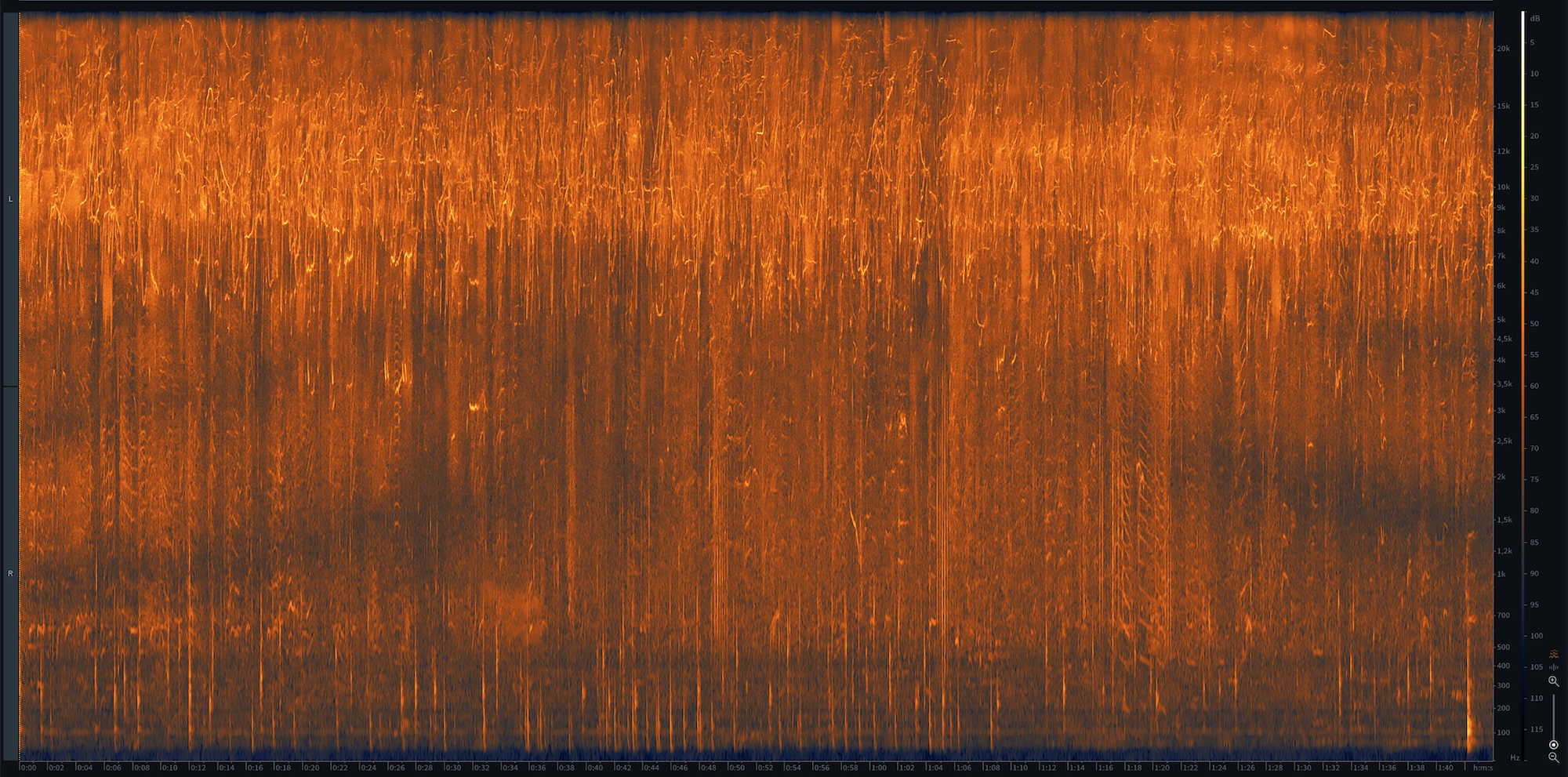

Carlos Casas, Bestiari (Dolphin Spectrogram), 2024, audiovisual film, [courtesy of the artist © Carlos Casas and Venice Biennale]

Dispute of the Donkey, a 1417 text by the Franciscan monk Anselm Turmeda, in which a donkey debates a friar about the superiority of animal kind at court, offers one response. The donkey all but wins the debate until the friar’s final argument—Christ came to earth in human form—which highlights the anthropocentrism that has dominated conceptions of sentience, let alone sapience and existence, on Earth in the context of colonial modernity and what followed. The story forms the basis of Carlos Casas’ Bestiari, a 2024 Venice Biennale collateral event curated by Filipa Ramos. Collated in collaboration with field recordist Chris Watson and sound spatialist Tony Myatt, the sonic installation of loudspeakers emitted audio recordings of animals from Catalonia and elsewhere, including bats, bees, dolphins, donkeys, elephants, parrots, and snakes, alongside film from parks across Catalonia rendered from each animal’s point of view.

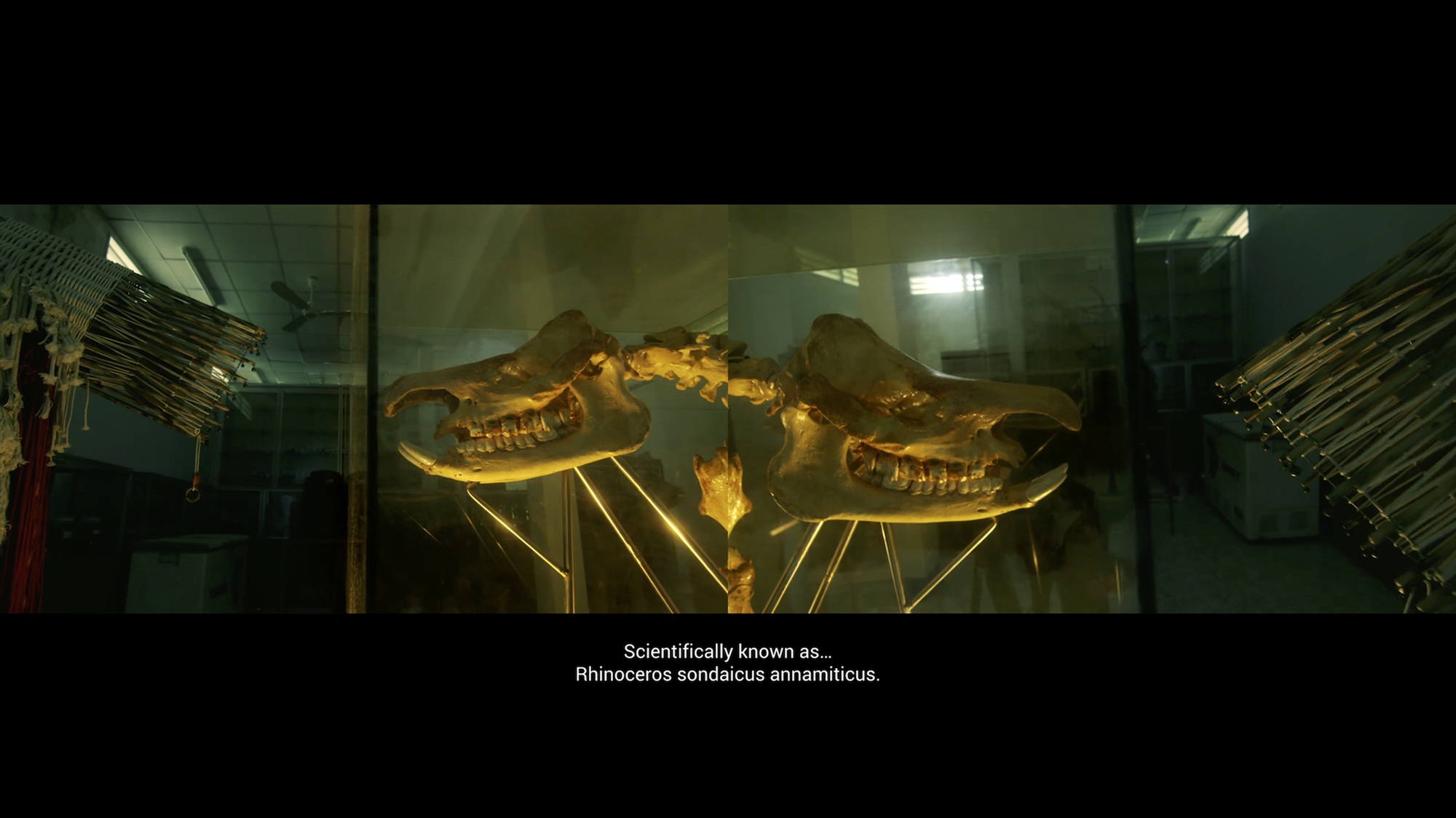

Alberta Whittle’s single-channel video A Black footprint is a beautiful thing (2021), imagines words for such views, when the voice of the shipworms that terrorised European colonizers and slave traders by eating through their wooden vessels, describe lying in wait to wreck ships intent on murder. As does Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s two-channel video installation My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires (2017), which speculates on the nonhuman voice in relation to the longue durée of anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist struggle. Over images of live animals and their representations as sculptures and shrines, a conversation unfolds between the last Javan rhinoceros in Vietnam—poached for its horn in Cát Tiên National Park in 2010—and Cụ Rùa, a Yangtze giant softshell turtle believed to be an incarnation of the Golden Turtle God Kim Qui, whose sword ended Chinese rule in Vietnam, found dead in Hoàn Kiếm Lake in 2016.

At one point in My Ailing Beliefs…, the rhino describes a Saigon Zoo uprising, when tigers—their keepers having sold their feed—“fought bravely against their captors, their colonizers.” While the turtle argues against violence and acknowledges survival as a common goal, the rhino warns against romanticizing animal relationships with humankind even if “times were difficult for all.” Expressing contempt for colonizers and the oppressed who have become oppressors out of greed, the rhino rages against humans worshipping animals in temples while butchering them in slaughterhouses: “There’s a certain kind of violence in the way they look at things, in the way they consume images, and the way they obsess over forms.”

Andrew Tuan Nguyen, My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires, 2024, two-channel video installation, color, 5.1 surround sound, 18:51 [courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York, © Tuan Andrew Nguyen 2024]

Andrew Tuan Nguyen, My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires, 2024, two-channel video installation, color, 5.1 surround sound, 18:51 [courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York, © Tuan Andrew Nguyen 2024]

The rhino’s vow to haunt “the oppressive human species, with the black magic of their own imaginations,” recalls Moby Dick as a spectral projection: an embodiment of Sartre’s warning in his preface to Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth that colonial violence will always boomerang to its source. “The normal behaviour of the starving is violence,” the rhino says, quoting Novo Cinema filmmaker Glauber Rocha. “It should be learned that an aesthetic of violence, before being primitive, is revolutionary.” The rub, however, is that in historical capitalism, revolution is a face-off. “I’d rather die before becoming extinct,” the rhino states, before quoting Huey Newton: “The first lesson a revolutionary must learn is that he is a doomed man.” Those words amplify the nihilism of the whaler’s motto, “A dead whale or a stove boat,” in relation to the revolutionary call for liberty or death. Both proclamations distill into kill or be killed.

IV. The Rights of Nature

How does a revolution against the forces of colonial modernity, whose plan of capitalist expansion at the cost of life has evolved into the present state of the world and its genocidal impulses, become a whole earth endeavour: a victory over death? The question demands a decentring of the human experience to understand this planet as a living system of earthly relations beyond the (technocratic, logistical, structural, hierarchical, political, ideological, economic, spiritual, imperialist) tyranny of capitalist production that has shaped world history for centuries through the violence and aftereffects of colonisation and neo-colonisation (read: imperialism).

As Dispute of the Donkey locates nature’s rights in the medieval courtroom, recent struggles have taken the fight to the international legal system in order to craft a new planetary contract through its institutions (though recent events in Palestine have shown what little power these institutions have in the context of the so-called international community). In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to recognize nature, referred to in Andean Indigenous cultures as Pachamama, as a legal entity—a milestone that artists Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares’ video installation Forest Law (2014) tracks through the Runa people of the Sarayaku’s struggle against the oil industry. The next year, a Bolivian referendum approved a constitution acknowledging the importance of protecting nature. But, as Lorna Muñoz notes, the two laws established in 2010 and 2012 to enact nature’s rights were watered-down versions of a draft law agreed upon by Bolivia’s government and a coalition of agrarian/Indigenous organizations, but never adopted, which would have upheld the rights of Earth whenever a conflict of interest arose.32

Then, in 2017, the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act of 2017 became “the first piece of legislation in the world to declare a river a legal person.”33 Established in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and rooted in Māori law and spiritual values, the act includes “expressions, like ‘Ko au te Awa, ko te Awa ko au: I am the River and the River is me.’”34 The phrase recalls South African High Commissioner to Canada Rieaz Shaik’s 2024 statement on South Africa’s application to the International Court of Justice—invoking the Genocide Convention against Israel in 2024, another white whale in modernity’s room—when he referred to the African philosophy of Ubuntu, commonly summarized as “I am because you are,” and the Dakota philosophy of Mitakuye Oyasin that “All are related.” Both perspectives on mutual relation recall Thomas Berry’s assertion that “the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.”35

Berry was an early proponent of Earth jurisprudence, which recognizes the failure of legal systems to protect the planet, “in part because they reflect”—per environmental attorney Cormac Cullinan—“an underlying belief that humans are separate from and superior to all other members of the community, and that the primary role of Earth is to serve as ‘natural resources’ for humans to consume.”36 But while the development of nature’s rights and legal personhood are transformative, they remain “inherently anthropocentric,” write scholars Erin O’Donnell, Anne Poelina, Alessandro Pelizzon, and Cristy Clark: “Nature has no need of these particular rights unless it is participating within human legal systems.”37 There also remains a “risk of environmental colonialism,” which involves erasing Indigenous peoples from the concept of nature—a dynamic D’Amato and Chopra seem to enact by challenging Indigenous claims to hunting as part of a culture of sustainable subsistence.

Andrew Tuan Nguyen, My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires, 2024, two-channel video installation, color, 5.1 surround sound, 18:51 [courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York, © Tuan Andrew Nguyen 2024]

The idea of re-imagining a planetary social contract through the international legal system, which is ultimately rooted in the history of colonial modernity, remains problematic for that reason. As O’Donnell et al. write, “settler-colonial laws may seek to embed Indigenous values within existing colonial legal frameworks, in the attempt to attain some form of weak legal pluralism [wherein] the Indigenous legal ‘other’ is reinscribed and ultimately assimilated within the colonial project.” Hence, the rhino and turtle’s disappointment in My Ailing Beliefs, “with postcolonial Vietnam’s inability to see … its exploitation of animals as analogous to the patterns of colonial domination that characterize its history … despite the foundational nature of this country’s hard-fought autonomy,” writes Godfre Leung.38 In Vietnam, “extinction is a layered predicament resulting from multiple colonialisms over millennia. Vietnamese self-determination, from the Chinese, French, Japanese, and Americans, is deeply entangled with environmental biodiversity’s ability to sustain on an infrastructural level.”

That colonial domination, “which in its wake dispossesses not only Indigenous lands but also entire Indigenous ontologies, is thus both laid bare and radically challenged by the emergence of an ecological jurisprudence,” write O’Donnell et al. As research agency INTERPRT demonstrates in the video Treacherous Journey (2023), a fundamental difference in scale and culture exists between industrialized and Indigenous farming traditions. On the construction of a wind energy project in Norway that disrupts seasonal migration routes for Sami reindeer herders, Ole Henrik Kappfjell describes a holistic relationship with the environment that defines Sami ancestral knowledge, which includes a culture of animal welfare. All of which underlines the fact that “The rights of nature concept is … more than a Western legal development,” per art historian T.J. Demos. “Rather, it’s embedded in long histories of Indigenous movements in the Americas”—and elsewhere—”that situate legality within diverse cultural traditions related to what is commonly termed buen vivir, or living well, in Andean cultures.”39

INTERPRT,Colonial Present: Counter-mapping the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in Sápmi,2023, 11.6.-22.10.2023, HAM Helsingin taidemuseo, Helsinki [photo: © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Sonja Hyytiäinen]

But it is important to note: the idea that “positioning rights of nature as a viable counter-narrative to Western developmentalism, means returning to some idealized and mythical pre-Columbian”—or any other—“origin,” is far from the point.40 Biologist Eduardo Gudynas describes buen vivir as an antidote to the zombie narrative of Western development: a living practice that opens up “common ground where critical perspectives on development, originated from different ontologies, meet and interact.”41The aim is to transcend “a historically situated divide between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’” and make “space for a more pluralist legal paradigm that re-centres Indigenous worldviews.”42 As Journalist B. “Toastie” Oaster writes, such worldviews represent “methodical and scientific practices, refined over thousands of years and designed to manage balanced and biodiverse ecosystems.”43

The task at hand, then, as Leung writes in response to My Ailing Beliefs…, is to develop a politics of true intersectionality that draws connections across struggles, both human and non-human, while holding ground for Indigenous knowledges and practices that never saw Earth and its inhabitants as objects of exploitation or as property to own in the first place. “One of the main tenets of Marxism is class-consciousness, namely for the exploited classes to recognize their mutual conditions of exploitation and revolt,” Leung notes, recalling the microcosm of the Pequod. “Intersectional solidarity is also, of course, a key point for the resistance to colonialism, one of whose primary strategies is to divide and conquer.” To dismantle the colonial structures that continue to shape the world today, solidarity must become a whole earth endeavour.

V. “Diving into the Wreck”44

Stove by a Whale—a 2024 collaborative exhibition by Steven He and Seongeun Lee, curated by Jiayue He, at Staffordshire St gallery in London—staged the aftermath of a shipwreck. In the gallery, pieces of ship rested amid beachlike rockscapes embedded with objects sourced from mudlarking on the river Thames. Among the workshops organised was a session with artist Bettina Fung that invited people to imagine journeys taken by their ancestors and to create crayon rubbings and paper boats, which were then added to the installation. The idea, He notes in a video tour with One Third Art, was to open a passage between old and new worlds: “The shipwreck itself represents the site of a ruin, or the shedding of connections to an old community. This is essential for new progress to begin and for new connections to be made.”

Steven He and Seongeun Lee, Stove By A Whale, installation view, 2024 [photo: George Baggaley; courtesy of the artist and Staffordshire St Gallery]

Steven He and Seongeun Lee, Stove By A Whale, installation view, 2024 [photo: Steven He; courtesy of the artist and Staffordshire St Gallery]

As Moten says in Tsang’s MOBY DICK, the story—of an oceanic rebel, a capitalist colonizer, and the ship caught between them45—is open-ended: “A network of future input. A work in progress, long drawn out, with no pre-set boundaries, no logical endings, only an infinity of ‘in the beginnings.’”

Between a whale and a boat, between the human and nonhuman, between land and sea, between old and new worlds, there exists a vast and revolutionary unknown. Like that which professor and human rights attorney Noura Erakat calls forth in the context of Palestine, where discussions on sovereignty have been co-opted to reinforce colonial power’s zero-sum death drive and its belief that “there can only be one sovereign over the land”—a politics not just of proprietorship over custodianship but of coexistence after violence. “What happens when we discard sovereignty and think about our relationship as a relationship of belonging, which is infinite?” Erakat asks. “In that relationship of belonging, is a responsibility.”46

Core to this re-alignment is a reacquaintance with Earth as a shared home, bearing in mind that sentience, as scholars Douglas Brock and Stanislav Roudavski point out, “is a constructed concept,” whose characteristics in nature “are common, varied and possibly omnipresent.”47 There is work to be done, too, in reconceptualizing practices of living beyond a system rooted in the history of capitalism, colonization, slavery, and their industrialization: an international world order whose basic unit—the state, the nation, the economy—was designed to service colonial modernity, and whose counter-histories include the 19th century’s fighting whales. What kind of planetary contract might this new world have?

John Huston, Moby Dick, 1956, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube]

References

| ↑1 | C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live in (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001), 44. “The whale-ship is also a factory.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Introduction to Into the Deep: America, Whaling and the World, PBS.org, aired May 10, 2010 |

| ↑3 | Herman Melville, Moby-Dick: Or, the Whale, Vol. I (Edinburgh University Press: Constable and Company Ltd. 1922), 259 |

| ↑4 | J.N. Reynolds, Esq. “Mocha Dick: Or the White Whale of the Pacific: A Leaf from a Manuscript Journal,” The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Magazine, May 1839, Vol. 13, No. 5, pp. 377-392 |

| ↑5 | Emily Irwin, “The Spermaceti Candle and the American Whaling Industry,” Historia 21 (2012), 45 |

| ↑6 | Bob Johnson, “A Peculiarly Valuable Oil: Energy and the Ecology of Production on an Early American Whale Ship,” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, 2014, Vol. 40, No. 1/2, 35 |

| ↑7 | See: John R. McNeill, “Bison, Elephants, and Sperm Whales: Keystone Species in the Industrial Revolution,” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 2023, Vol. 48, No. 1, 162 and Charles Solomon, “‘The Whale’ by Philip Hoare,” The Los Angeles Times, February 25, 2010 |

| ↑8 | Bathsheba Demuth, “Overview: Harvesting Light: New England Whaling in the Nineteenth Century.” Energy History Online, Yale University, 2023 |

| ↑9 | David Haines, “Lighting up the World? Empires and Islanders in the Pacific Whaling Industry, 1790-1860,” in Maritime History as Global History (eds. Maria Fusaro, Amelia Polonia) (Liverpool University Press: 2017), 159 |

| ↑10 | Tom Kizzia, “Whale Hunters of the Warming Arctic,” The New Yorker, September 5, 2016 |

| ↑11 | Jorge Vargas, “The California Gray Whale: Its Legal Regime Under Mexican Law,” Ocean & Coastal Law Journal, Volume 12, Number 2, (2006), 220-221 |

| ↑12 | James Williford, “Whaling the Old Way,” Humanities, March/April 2010, Vol. 31, No. 2 |

| ↑13 | ibid. |

| ↑14 | Lissa Wadewitz, “Animals, Race, and the ‘Gospel of Kindness’: The American Whaling Fleet of the Pacific World,” in Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans, and Pacific Worlds, eds. Ryan Tucker Jones and Angela Wanhalla (Honolulu: University of Honolulu Press: 2022), 30. Consider, also, the initial 20 survivors of the Essex, who spread out across three life boats and after weeks at sea succumbed to cannibalism to survive, with four men on one boat pulling straws to decide who should die to feed the others (they shot the captain’s teenage first cousin). |

| ↑15 | Herman Melville, Moby-Dick: Or, the Whale, Vol. I (Edinburgh University Press: Constable and Company Ltd. 1922), 234-236 |

| ↑16 | Philip Hoare, “Sperm whales in 19th century shared ship attack information,” The Guardian, March 17, 2021 |

| ↑17 | Herman Melville, Moby-Dick: Or, the Whale, Vol. II (Edinburgh University Press: Constable and Company Ltd. 1922), 127 |

| ↑18 | Anthony D’Amato and Sudhir K. Chopra, “Whales: Their Emerging Right to Life,” The American Journal of International Law, Jan., 1991, Vol. 85, No. 1 (Jan.,1991), 26 |

| ↑19 | Bathsheba Demuth, “Whale Country: Bering Strait Bowheads and their Hunters in the Nineteenth Century,” in Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans, and Pacific Worlds, eds. Ryan Tucker Jones and Angela Wanhalla (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press: 2022), 154 |

| ↑20 | Bob Holmes, “If you think a crow is giving you the evil eye…” NewScientist, January 26, 2010 |

| ↑21 | Joseph Castro, “Grudge-Holding Crows Pass on Their Anger to Family and Friends,” Discover Magazine, June 30, 2011 |

| ↑22, ↑30 | David Foster Wallace, “Consider the Lobster,” Gourmet, August 2004 |

| ↑23 | Lissa Wadewitz, “Animals, Race, and the ‘Gospel of Kindness’: The American Whaling Fleet of the Pacific World,” in Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans, and Pacific Worlds, eds. Ryan Tucker Jones and Angela Wanhalla (Honolulu: University of Honolulu Press: 2022), 30 |

| ↑24 | Quoted in Bob Johnson, “A Peculiarly Valuable Oil: Energy and the Ecology of Production on an Early American Whale Ship,” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, 2014, Vol. 40, No. 1/2, 44 |

| ↑25 | C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live in (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001), 5 |

| ↑26 | ibid., 14 |

| ↑27 | ibid., 33 |

| ↑28 | ibid., 13 |

| ↑29 | Anthony D’Amato and Sudhir K. Chopra, 26 |

| ↑31 | Bathsheba Demuth, “Whale Country: Bering Strait Bowheads and their Hunters in the Nineteenth Century,” in Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans, and Pacific Worlds, eds. Ryan Tucker Jones and Angela Wanhalla (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press: 2022), 148-152 |

| ↑32 | Lorna Muñoz, “Bolivia’s Mother Earth Laws: Is the Ecocentric Legislation Misleading?” ReVista Harvard Review of Latin America, February 6, 2023 |

| ↑33 | Mallory Jang, “Rights of Nature and Indigenous Peoples: Navigating a New Course,” Peter A. Allard School of Law, Centre for Law and the Environment, University of British Columbia blog, September 2, 2021 |

| ↑34 | Ibid. |

| ↑35 | Thomas Berry, Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as Sacred Community (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2006), 17 |

| ↑36 | Cormac Cullinan, “Earth Jurisprudence: From Colonization to Participation,” in State of the World 2010: Transforming Cultures, From Consumerism to Sustainability (New York: Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc. 2010), 143-144 |

| ↑37 | O’Donnell, Poelina, Pelizzon, and Clark, 7 |

| ↑38 | Godfre Leung, “’The Black Magic of Their Own Imaginations’: Notes on Extinction,” in the exhibition catalogue for Andrew Tuan Nguyen: RỪNG HOANG: EMPTY FOREST, at Factory Contemporary Arts Centre, Ho Chi Minh City (December 9, 2017–February 7, 2018), 46-48 |

| ↑39, ↑40 | Demos, 7 |

| ↑41 | Eduardo Gudynas, “Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow,” Development, 2011, 54(4), 447 |

| ↑42 | O’Donnell, Poelina, Pelizzon, and Clark, 3 |

| ↑43 | B. ‘Toastie’ Oaster, “Questions about the LandBack movement, answered,” High Country News, August 22, 2022 |

| ↑44 | A poem by Adrienne Rich, which is quoted by Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme in the video installation And yet my mask is powerful |

| ↑45 | My own summation |

| ↑46 | Céline Semaan, “On Palestine: An Open Conversation with Noura Erakat,” Slow Factory |

| ↑47 | Douglas Brock and Stanislav Roudavski, “Sentience and Place: Towards More-than-Human Cultures,” in Why Sentience? Proceedings of the 26th International Symposium on Electronic Arts (ISEA 2020) (eds.) Christine Ross and Chris Salter (Montreal: Printemps Numérique/ISEA, 2020), 84 |