TJ Shin: Unbecoming Human

Share:

Los Angeles–based artist TJ Shin’s work centers on living processes. It explores the felt experience of postcoloniality through intimate sensorial responses. In their work—often conveyed through installations—digestion, fermentation, transformation, and transition emerge as systems of understanding internal, bodily responses to landscapes of confinement and control.

Throughout their practice, Shin takes on many guises—the artist, the biologist, the fermenter, the alchemist—all of which point toward living connections between the body and the embodied. Their latest installation, The Vegetarian, explores porous boundaries between human and nonhuman, inspired by author Han Kang’s 2007 novel of the same name. In the book, a young woman, haunted by visceral dreams of animal carnage, refuses to continue eating meat, alienating herself from her family as she slowly transforms to a vegetative state. Taking the book as a point of departure, Shin’s work examines shifts between gender, genus, and consciousness, queering the boundaries between the human and nonhuman, living and dead.

Through scientific inquiry, Shin identifies a cross-species connection between the woman in Han’s story and mugwort, a flowering plant that has historically been used in treatments for malaria, but has also been categorized as an invasive species in North America. In transfecting, or introducing, their DNA to the plant’s genome, Shin reveals overlapping solidarities between otherized people and contagions. Even as a cure, mugwort is often viewed as a pest, a toxin, an invader, categorizations that are often levied against racialized, gendered, and/or disabled bodies. In contemplating this duality, Shin demonstrates the ways in which embodied knowledge produces a multiplicity of existences.

Re’al Christian: Let’s start with your current show, The Vegetarian. Could you speak about the installation, how it originated, and the objects, actions, and scents that activate the space?

TJ Shin: Sure. The Vegetarian started … with a residency at the University at Buffalo, where I collaborated with a biologist, Solon Morse …. I brought in mugwort, [one species of] which is considered an invasive species in North America, and I wanted to transfect my DNA [into the plant’s] and think about the enmeshment of plant and animal matter. After doing the transfection process [by] using a gene gun, commonly used for agricultural industrialization or modifications, the lab asked me—and instructed me—to kill the leaves, out of fears of, first, mugwort being an invasive species and, further, invading the leaves with my DNA through the mutagenesis process.

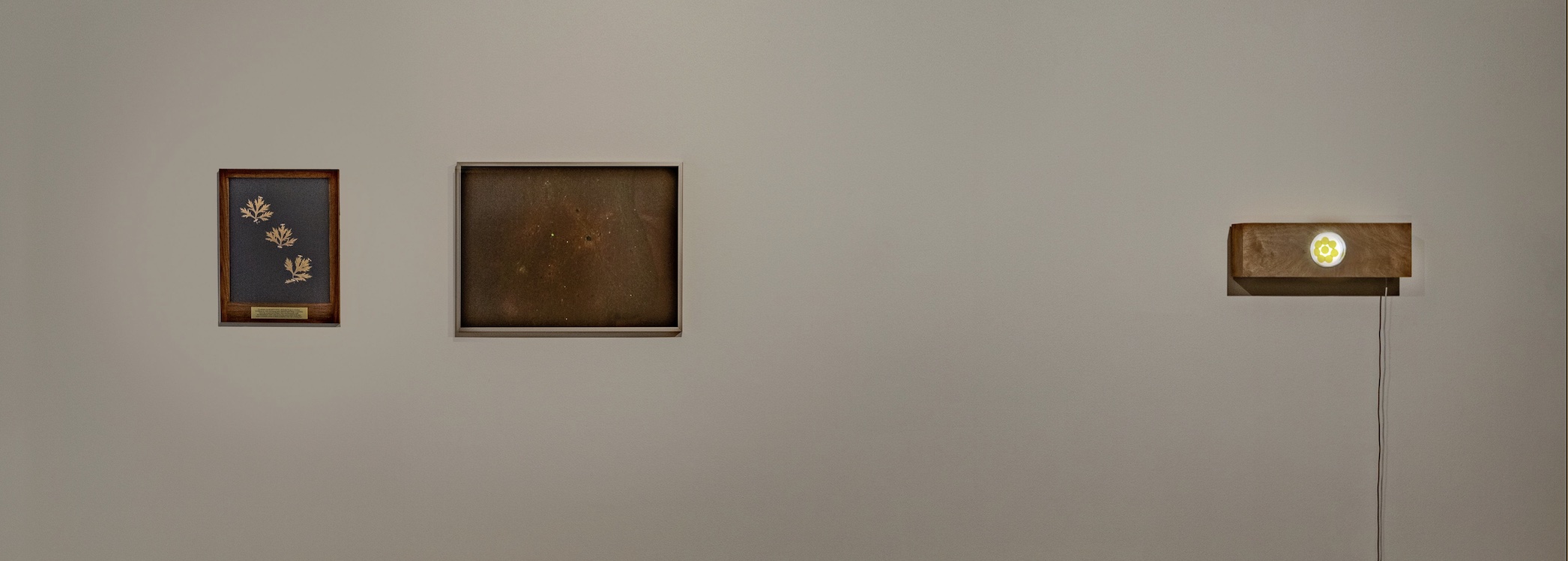

TJ Shin, Mourning Portrait 3, 2022, preserved transfected mugwort with artist’s DNA, etched plaque, wood, 11 x 14 inches [photo: Katy Whitt; courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

TJ Shin, Mourning Portrait 2, 2022, preserved transfected mugwort with artist’s DNA, etched plaque, wood, 11 x 14 inches [photo: Katy Whitt; courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

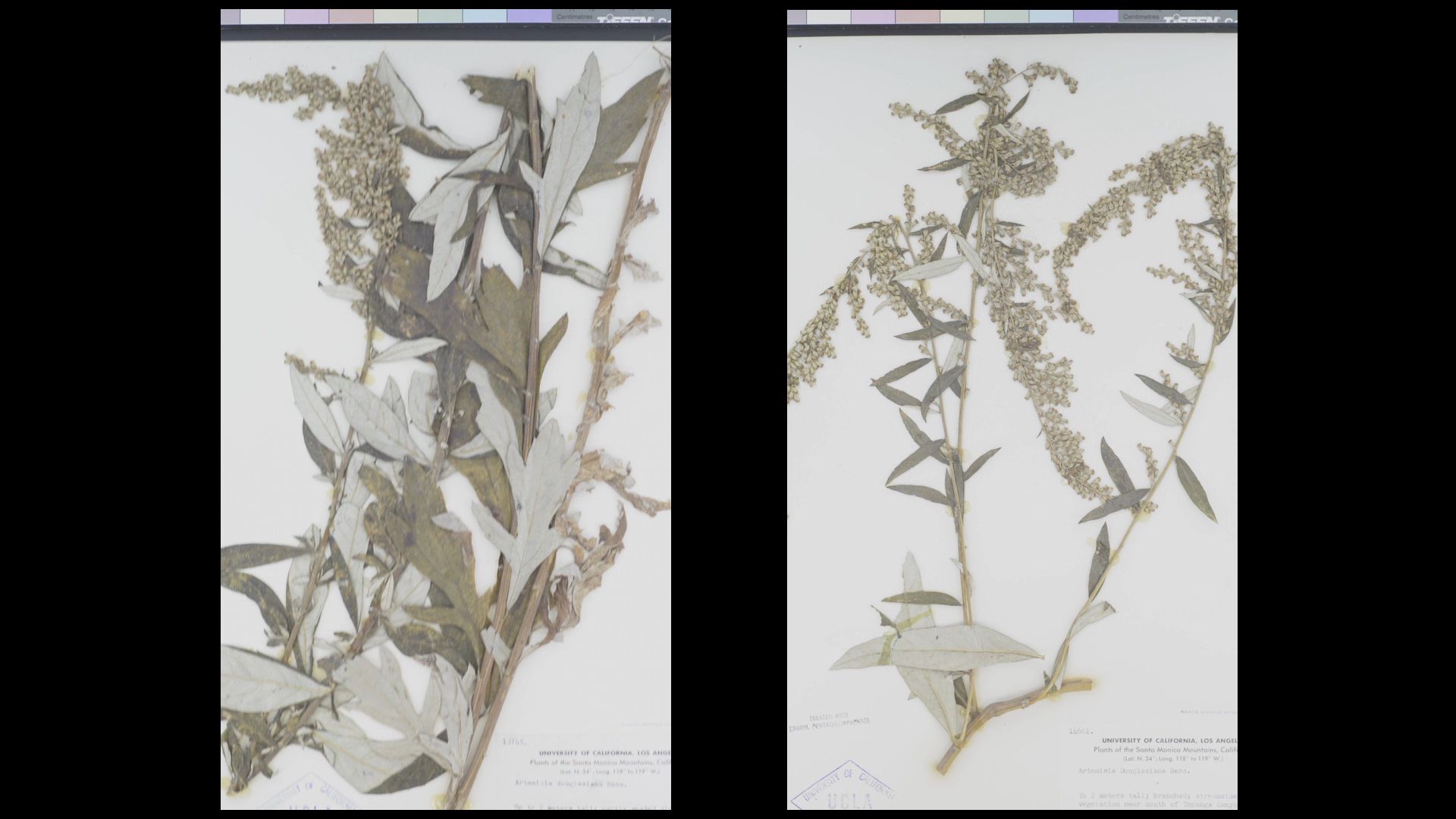

And so, thinking through the lab protocols and what it means to become an invasive species—or a pest, so to speak—I was really interested in the categorizations and taxonomies of invasion, the native, and naturalization. And, throughout the process, I also weaved my research of the material histories of mugwort. First, I was thinking about the origin story of Korea, where the bear eats nothing but divine mugwort and 20 cloves of garlic for 100 days in a cave to become the first human, a woman. Second, thinking about mugwort as an antimalarial drug that was heavily tested and extracted into what we know as artemisian, which [was] the only [effective treatment for all strains of] malaria at [that] point—during the Vietnam War. And also weaving [in] John MacCulloch, the geologist who coined the term malaria in the English language in his treatise in 1827. I was also thinking about Yeong-hye, who is the fictional character in the book The Vegetarian [by Han Kang]—where the title of the exhibition comes from—to think about forms of dehumanization, deformation, and transubstantiation.

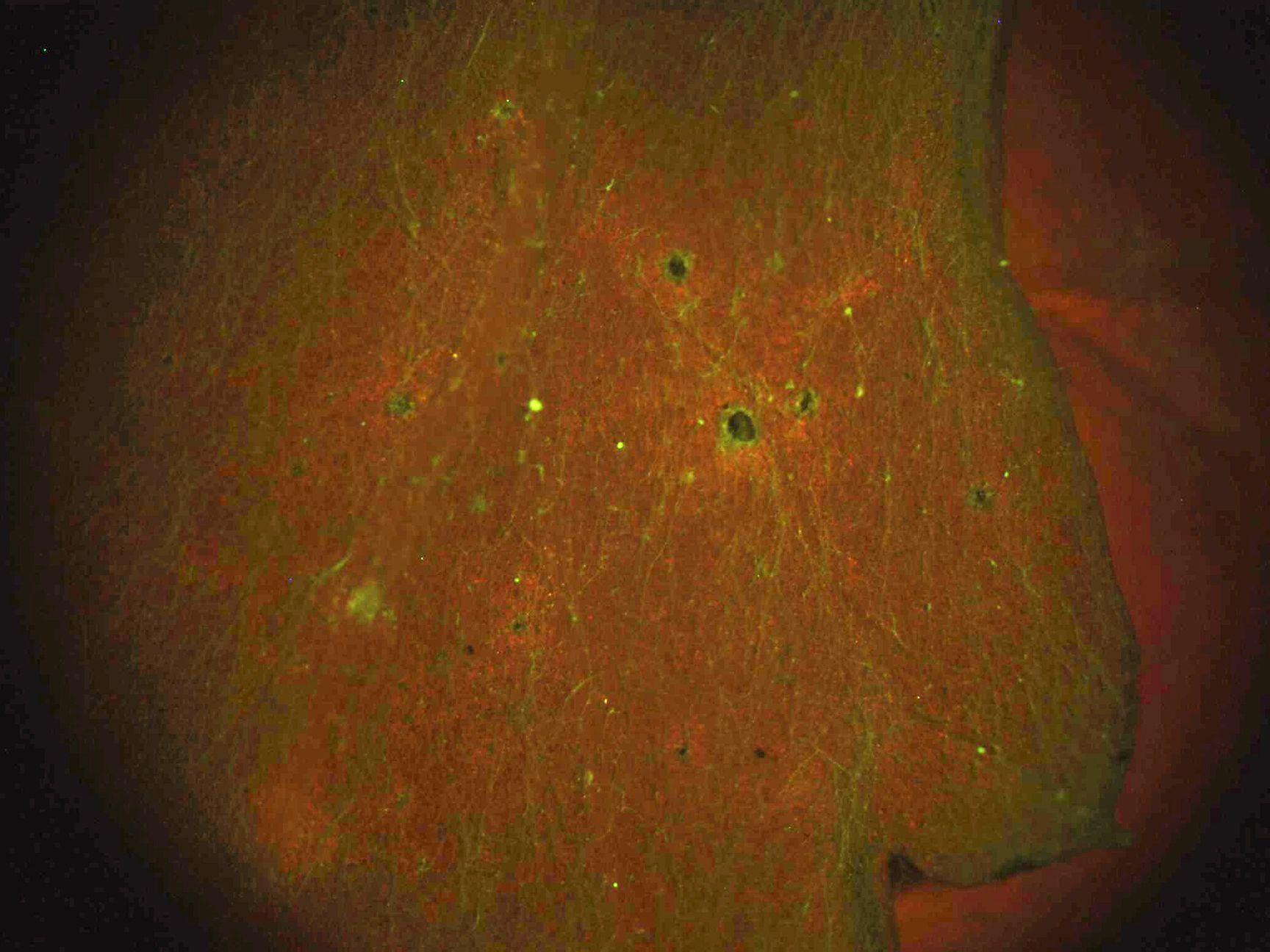

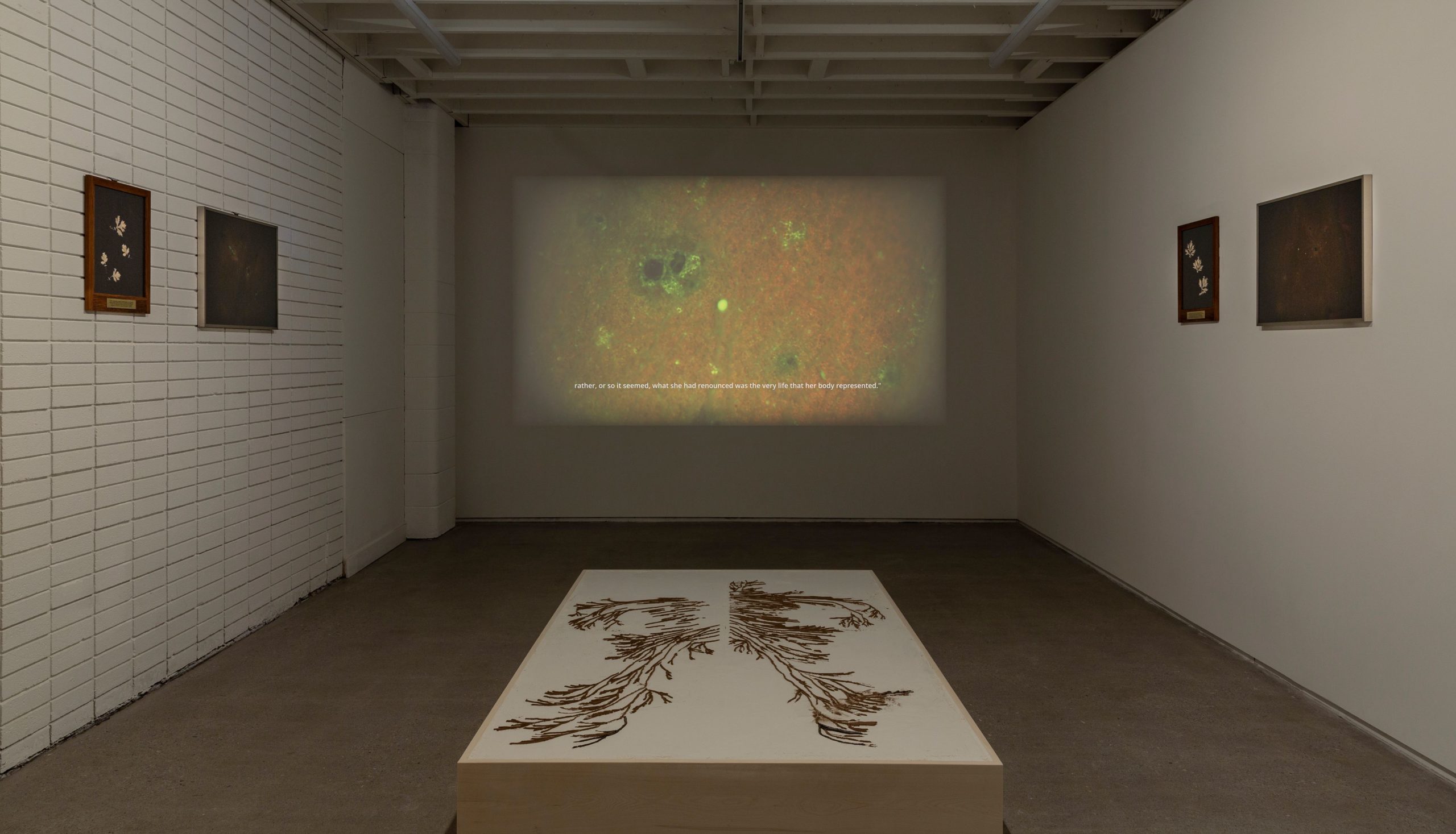

So, in the actual space, I have the dried mugwort leaves pressed as herbarium collages, and digital scans from the microscope showing the transfection process, where my DNA is expressed in fluorescence onto the mugwort leaves. Centrally in the space is a large scentscape of a vascular body—a quasi-mushroom, mycelian network [of] the nervous system of the human body or bodies of lakes, but traced [in] incense [consisting of] various materials: for example, the transfected mugwort; cinchona, which was [used to make quinine,] the precursor to mugwort [as an] antimalarial drug; and other tannins and oak trees that were thought to remedy malarial symptoms.

TJ Shin, The Vegetarian, installation view, 2022 [photo: Katy Whitt; courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

RC: I love these connections you’re drawing between different plant and animal species, and the human body. It’s a connection that we don’t often address … between animal rights activism [and] human rights—[and, likewise,] the way that we approach health in different cultures from different perspectives. And so, I think it’s interesting that the lab encouraged you to dry the leaves to destroy this new species that you were creating. Is that where Mel Chen’s concept of transplantimalities, or tranimals, comes in, and how that [concept] articulates connections between species, gender, and race?

TJ Shin, Untitled (Self-Portrait 3), 2022, digital print from microscope scans

TJS: Yeah, definitely. I was thinking about transplantimalities, which is a term that Mel Chen introduces in their interview in Transgender Studies Quarterly, where they describe trans-species organ transplantation. They describe an instance in which the recipient of the organ transplant can almost feel the organ donor. So, I was thinking about what it would feel [like] for the mugwort plant to recognize me, or to metabolize me in its vascular stomatal pores, if it would recognize me as an invasion, or form a sort of queer allyship, in a sense, of my so-called Asiatic pestilence. What was interesting, too, in the lab, in their instruction to dry my leaves, was [that] they were very reluctant to accept my proposal in the beginning, out of fears of agricultural contamination, and [fears] that the mugwort would actually invade their laboratory walls.

[I was] thinking about what it means to be a pest, or to be diseased or contagious, and about how the definition of the pest is a living organism that causes damage or illness to Man, or his possessions, or his private property. So, [a] pest really is a body that is perceived as a threat of economic loss or damage, and really infracting on the boundaries of private ownership. So there is this desire or fantasy of human domination in the microcosm, in the lab itself, and the desire to be self-contained and pure, to create this idea of uncontaminated human subjectivity. And so, in transfecting the mugwort, their instruction to dry the leaves, I thought, was really echoing the Western [practice] of herbariums, where the tradition of taxonomizing, categorizing, cataloguing species for containment for study [and] extraction speaks to the process in which I was studied, I was categorized, I was taxonomized. My effort to make the scentscape [came out of] my desire to think about the pestilent social life of the mugwort, and to be ungovernable, and to refuse this mastery. To burn the dry, transfected leaves in the space for the audience to smell, to metabolize, is to re-materialize the figure of the pest, and to use a scentscape that [was] once [conceived as a means] of deodorization, or purification, to actually think about intoxication, or to re–incite anxieties of atmospheric risk.

TJ Shin, The Vegetarian, installation view, 2022 [photo: Katy Whitt; courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

TJ Shin, The Vegetarian, installation view, 2022 [photo: Katy Whitt; courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

RC: What you’re saying is reminding me [of] colonization efforts beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, and this desire for cleanliness, to eradicate—but also control and impose order on—the colonial body, which was perceived as invasive, even in its Indigenous space. In those efforts to colonize, to transplant this sense of order, there was the introduction of parks and of cultivated greenery, which [offers another] layer of kinship, [or] allyship, between plants and the colonial body, [which was also] subjected to this kind of control.

TJS: Yeah, I think about the borders of the garden—botanical gardens, public parks, all the way to the laboratory or the backyard garden. In a sense, these colonial forces shape the boundaries of the garden, where we’re really enacting the administration of life—what gets to live, what gets to die. It really speaks to the way that we think about pharmacology and pharmakon. In the research of The Vegetarian, I was interested in the episteme of medicine and how traditional medicine becomes an object of knowledge for colonial rule and expansion, aka pharmacology, and how these shifting categories of cure and poison become established into what [chemicals are most effective], and how this is, in a sense, a practice of gardening.

Pharmakon is a useful framework [for] the administration of remedy, poison, and scapegoat. I was thinking [about] how they all constitutively work together, that [each] one cannot understand the [others]—that, for example, a cure demands sacrifice, or that poison requires an antidote, and the notion of healing persists on malady. Again, they’re all coterminous. And in doing my research on mugwort, I was thinking of the indentured “coolie“ labor that harvested the cinchona bark, for example—which was the only cure for malaria at the time—that was transplanted from Peru to Java. Coolies were [seen as] responsible somehow for the transmission of the malarial parasite but indispensable for the cultivation of this “Jesuit’s bark” that was considered the bark of all barks. Without quinine, which is extracted from cinchona, the penetration of Africa and expansion by the colonial powers would not have been possible.

So, again, there are these shifting categories of what’s cure, what’s poison.

Mugwort was also introduced in ballast by Jesuit missionaries. It’s considered an invasive species in North America, yet indispensable for the cure [for] malaria, and what accelerated Communist expansion [in] Asia. So, there are all these shifting taxonomies that, in thinking about pharmakon, [inform] how colonialism sustains its organizations and reinforces its own power relations.

RC: You mentioned Han Kang’s novel The Vegetarian as the inspiration for the title of your show. In the book, the protagonist [Yeong-hye] becomes a vegetarian quite suddenly, to the dismay of her family. She’s subsequently ridiculed, even persecuted, through various patriarchal structures—her family being one of them and the other being the healthcare system itself. She’s institutionalized for her embrace of plants and her perceived obsession and mania. She transforms into something plantlike—a tree, something nonhuman, at first metaphorically, and then literally. I’m thinking about these human and nonhuman relationships, this cyclicality and how the protagonist is then treated as an invasive species herself that needs to be controlled, placed within a structure that can contain her.

I brought up the idea of witches [in an earlier conversation] and how the protagonist’s treatment in the novel bears this relationship to the treatment of witches, women who similarly transcend the perceived boundaries between the natural and unnatural life and death, often drawing connections in kinship with nonhuman species. Could you talk a little more about the patriarchal delineations between the natural and unnatural, and how they form or inform the supernatural?

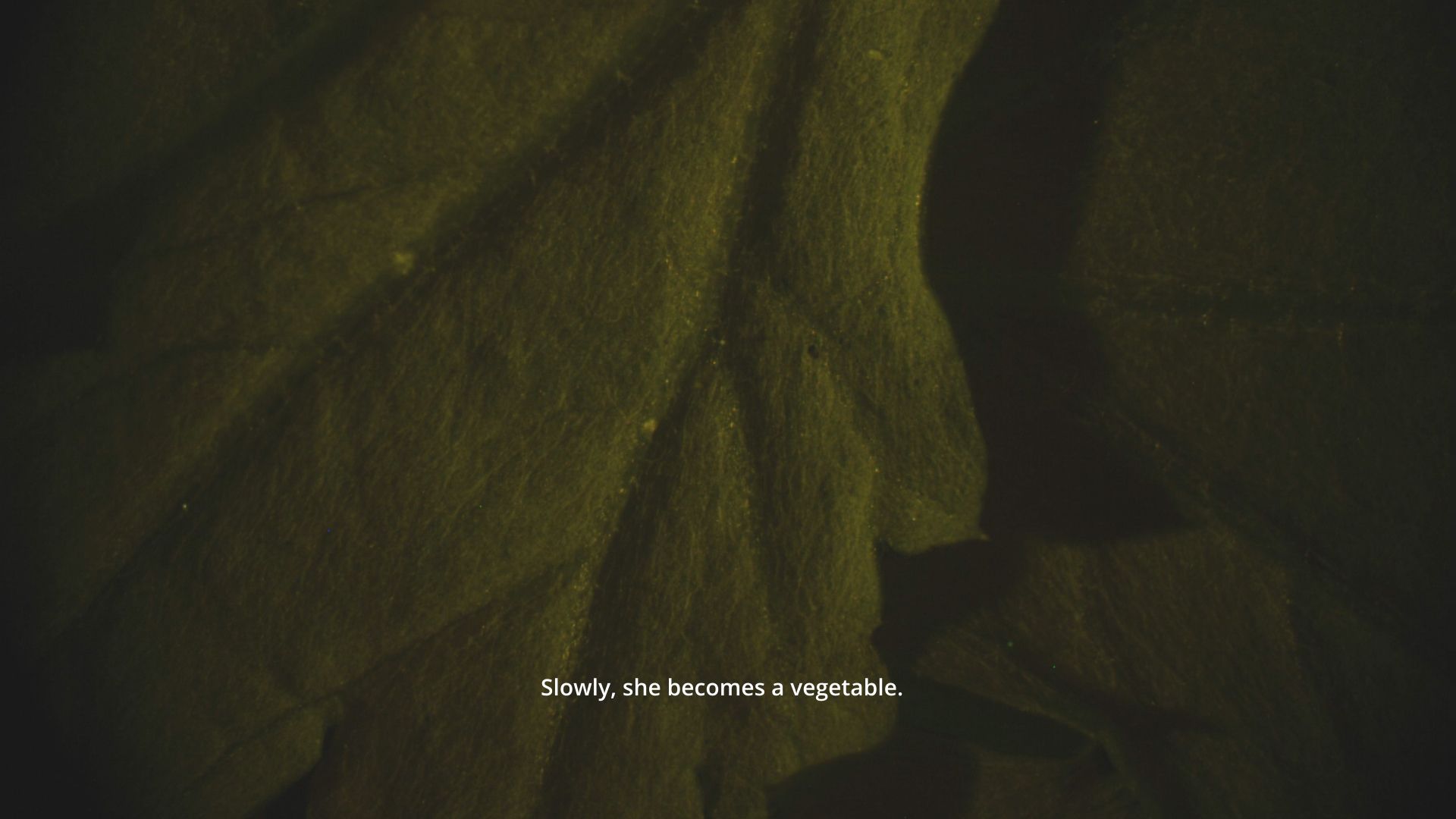

TJS: Yeong-hye starts out as a wife and a homemaker who has a nightmare about animal flesh and animal slaughter. Shortly after, she decides to be a vegetarian, and throughout the book, slowly, she becomes a vegetable. Rather than thinking about this act as self-denigration or self-harm, I wanted to think about her as [embodying] this radical refusal to be human. And so, [in] thinking about this idea of a vegetated life—which connotes the vegetative state in the medical field: minimally conscious, or comatose, or brain dead, or insensate—I’m really trying to reconsider the questions of what constitutes life—what does it mean [for her] to dehumanize herself and to become unhuman?

One scholar who’s been pivotal to this thinking, for me, has been Eunjung Kim. In her essay “Unbecoming Human: An Ethics of Objects” [in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies], Kim says that objecthood can be a mode to open up new ways of unbecoming human or dehumanization, and [that] embodying objecthood can be a way to open up anti-ableist and queer ethics to re-question the boundaries of the human, and that the human inherently creates exclusions of otherness.

RC: It also reminds me of that Mel Chen interview you mentioned, as well as their book Animacies, and how they speak about their relationship with trans studies as [being] from the perspective of a queer, trans, disabled person of color, and how approaching it through the lens of the nonhuman, and in deconstructing humanness—as opposed to animality, animalness—is a really productive way of breaking down the boundaries that humans create [which] make these kinds of distinctions more rigid than they need to be.

TJ Shin, Anthropology of a Phytomorphist, 2021-2022, video, 14:00, [photo: courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

TJ Shin, Anthropology of a Phytomorphist, 2021-2022, video, 14:05, [photo: courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

TJS: I think Chen also talks about how transing—which for them is about crossing, or destabilizing, or upsetting these human-made divisions of gender, race, and species—is not exceptional. And that Premarin, which is an estrogen made from urine of pregnant mares, was the standard prescription for a lot of transitioning women. This is an example of transplantmalities or transanimalities. I’m also reminded of Eva Hayward and Che Gossett [saying] that the human and animal divide is inherently a racial, colonial one. And so, in me transing with this invasive species, with my Asiatic pestilence, I’m really trying to understand what kind of active racialized fantasies or desires or anxiety I’m really reciting, and [to] think about ecological horror and bodily porosity.

RC: [Speaking about the bodily] brings me back to the scentscape that you described in The Vegetarian and how you’ve done other scentscapes before. One of the first shows I saw your work in was the show that you had with Jesse Chun at DOOSAN Gallery, stain begins to absorb the material spilled on, in 2020, which takes its title from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee. I really loved the connections in that show between language or speech and digestion as these two orally fixated processes of being in relation with [each other]. And maybe that also connects to your more recent work Vestibule, which focuses on the mouth as a site of consumption and violence and intimacy. I was wondering if you could speak about these works—the onggi [traditional Korean earthenware] and the vestibule. I’m interested in the ways in which you reveal our senses as these social boundaries.

TJS: I was really interested in onggi, where [you] glaze with Indigenous leaf molds to ferment foods like kimchi. The porosity of the ceramic material’s skin allows optimal airflow. It’s a breathing vessel, so to speak; it’s an extended organ. You would dig a hole in the ground as a traditional refrigeration method. In vitrifying this flesh to make it glassy, I’m trying to understand how vitrified skin is really nestled in the project of modernity and [how] to be literally pore-less. This project of deodorization or purification has so much to do with racialized and gendered fears of contagion and toxicity.

TJ Shin, stain begins to absorb the material spilled on, installation view, 2020 [photo: courtesy of the artist and DOOSAN Gallery, New York]

I’m also thinking about the other project, The Vestibule (between the teeth, lips and cheeks). Inside the glass vestibule, I had various ingredients like SCOBY, sugar, and tea. I also had [papers printed from] colonial archives, one of which was the British colonial office correspondence [which] showed that indentured Asian “coolie” labor will help suppress Black insurrection in the West Indies and further intensify the sugar plantation system. So, I’m thinking about how, in fermenting this probiotic tea, kombucha, how this mother SCOBY over time will devour the colonial archives, and speculating on the possibilities of toxicity, of rot and decay, breaking down these violent, intimate histories that are really infused with racial embodiment. Throughout my practice, I’m really questioning what are the divisions between the human and the nonhuman, what constitutes living and what’s dying, and how do these divisions really pertain to our hierarchies of gender, sex, and speciesism.

RC: I’m curious how you came to that story about the insurrections. That’s a history I’ve [heard only] a little about, and of course that’s a history that wouldn’t be taught very much in the US. Another aspect of colonization was the separation of colonial bodies, based [upon] the superficial delineations of race and ethnicity.

TJ Shin, Vestibule (between the teeth, lips, and cheeks), 2021, glass, screenprint, archive images, text from Sweetness and Power by Sidney Mintz and Intimacies of Four Continents by Lisa Lowe, vacuum seal, sugar, tea, SCOBY, 40 x 19 x 19 inches [photo: courtesy of the artist and Klaus von Nichtssgend Gallery, New York]

TJS: The archive was directly pulled from Lisa Lowe’s book The Intimacies of Four Continents. In her first chapter, she goes to the archives to show that indentured Asian “coolie” labor was indispensable to create a new economic system of new forms of slavery that would further curtail any forms of solidarity or allyship between Black, Indigenous, and Asian bodies. And Coolies were thought to be a literal skin barrier or barricade between the governing White bodies and the enslaved Black bodies. That essay was formative to my thinking and [was presented] alongside [the piece] inside the glass vestibule. I also had Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power to [help me] think about how the literal idea of sweetness comes from the violent colonial history of sugar used to further intensify the British industrial system. So, in tracing the material history of sugar plantations and indentureship, we can really parse … and flesh out how edibility and ingestion are inextricably tied [to] colonial forces of power.

RC: And that has contemporary resonance with our modern-day approaches to ideas of healthiness or healthfulness and food access.

TJS: Absolutely. [In] Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, I respond to the scientific research that was published in the journal Cell in 2018, that immigrants of color go through a process of gut colonization upon arriving in the United States, and that this [study] debunks a lot of the theories of health and cure and revitalization, [which say] that food in and of itself can aid rehabilitation. This study shows that these global forces of industrial agriculture and toxification with pesticides and insecticides and food deserts and all these greater forces literally, materially, shape our guts. Native gut microbes are eradicated and [the gut is] colonized by American ones. The study showed that certain vegetables [could no longer be as efficiently] digested, and that the [longer the immigrants] stay in the US, the more likely [it is] that these processes of gut colonization will be compounded. It’s a very dark, very necropolitical study, for sure.

RC: I’ve noticed that many of your works center [on] certain rituals, and I’m thinking of the Microbial Speculation installation at Recess, as well as installations [such as] M for Membrane (2020), which focused on rituals around ecological care and practices of fermentation, [and] older works [such as] Universal Skin Salvation (2018), which featured these custom-made compounds chemically and aesthetically inspired by Korean beauty products, and in which you engage … the idea of lactification or the whitening that these products promise. In these three installations, you draw connections between internal and external methods of care, and of understanding mental and physical health as permeable while also revealing the negative impacts of colonialism on accessing and developing our relationships with both personal and environmental health. I was wondering if you could speak about those projects, how rituals inform your work, and what conclusions—maybe nondefinitive conclusions—you draw from the beginning of a project to the end.

TJ Shin, Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, installation view, 2020 [photo: courtesy of the artist and Recess, Brooklyn]

TJ Shin, Universal Skin Salvation, installation view, 2019 [photo: courtesy of the artist and Lewis Center for the Arts, Princeton]

TJS: I’m really interested in all chemical transformations and to work with different materials, as you’ve outlined: lactic acid in Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings and Universal Skin Salvation; Indigenous leaf mold in M for Membrane; and other fermentative proteins and organic membranes. I work with these membranes to essentially animate transgressions and to destabilize intimacies among like species, including molecular and cellular and animal and vegetable and nonhuman life. I’m really interested in working with and collaborating with these actants, [and in] how to disavow object-oriented mastery and to destabilize vertical hierarchies of life. [There is often] an element of slow time in my practice, or a slow reading, where a lot of the material and affective intimacies that I’m building are nonspectacular. For Microbial Speculation of Gut Feelings, it took a course of six weeks to see the fermentation of lactic acid fertilize the soil. And only then could you see a slow progress of greens building. And there’s a consumption of these things at the end, and [a desire] to understand waste as this byproduct material.

In M for Membrane, after fermenting Indigenous leaf mold from the woodland gardens [at Wave Hill], it was returned back to the same site, but in a different form, as a liquid fertilizer. [Same] thing with Universal Skin Salvation: I fermented lactic acid to think about [the] lactification that Frantz Fanon proposed. [In the] active consumption [of] these gelatinous products, how do we enmesh ourselves with these ideas and these colonial fantasies? One of the themes that I’m thinking about is slow time and how [these] co–constituted becomings really demand [that we] look at these affective relations in slowness [under] their own terms so that we [can] really speculate on new modalities of life or new ways of becoming, rather than the spectacularized or romantic notions of solutions.

RC: Your installations really invite the viewer to be mindful of their body and the space, and of how there’s a durational quality to the work. I think, as humans, we’re not always mindful of the way that time is passing, of the rapidity of our gestures or the way that we move through the world in relation to other beings. I think that’s where the patriarchal conceit comes into the colonial conceit of expecting to force one’s will onto a being that contains multitudes of knowledge that we will never know.

What do you see as the afterlife of The Vegetarian?

TJS: That’s a good question. I was really thinking about these ideas of afterlife and alterlife. Not only in terms of the actual material affect of the work in terms of the smell, or scentscape, where you metabolize and carry the actual process of the transfection with you, out [of] the gallery.

TJ Shin, Universal Skin Salvation, installation view, 2019 [photo: courtesy of the artist and Lewis Center for the Arts, Princeton]

TJ Shin, M for Membrane, installation detail, 2019 [photo: courtesy of the artist and Glyndor House Gallery, NY]

But there was also a limited amount of the mugwort leaves that I was able to transfect. And so, in burning this material, I’m thinking about the afterlife and the alterlife of this process. The incense piece is on a bed of diatomaceous earth; ironically, it is used to lay down incense trails, but also [as] a pest insecticide. But once the incense trail is burnt, I’m interested in collecting the ash and seeing what forms and what stories this ash can tell, whether it be returning … to the earth in a different form or used to make a flux for the ceramic rocks.

One interesting note is that John MacCulloch, who introduced the term malaria—this was before the advent of the microscope—thought that it was decomposing rocks, and that [it was] this process between life and death, which is decay, that caused the putrefaction in malarial symptoms. And so, I’m interested in thinking about deformations or transubstantiation of decay, to think through the biopolitical, but also necropolitical, forces at work that shape vegetated life.

TJ Shin, Anthropology of a Phytomorphist, 2021-2022, video, 14:00, [photo: courtesy of the artist and The Bows, Mohkinstsis/Calgary]

Re’al Christian is a writer, editor, and art historian based in Queens, NY. Her work has appeared in BOMB BOMBMagazine, The Brooklyn Rail, Art in America, and ART PAPERS, where she is a contributing editor. She has written catalogue and exhibition texts for CUE Art Foundation, DC Moore Gallery, the Hunter College Art Galleries, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., and Performa. Christian received her MA in art history from Hunter College, and her bachelor’’s degree in art history and media studies from New York University.