Dark Study: on Emily Jacir, Forensic Architecture, and fugitive documentary

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, 2019, documentary, 43 minutes [©Emily Jacir; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Fugitivity, as it relates to Black study, has been a mode of contesting misrecognition through a lens of narrative darkness. By narrative darkness, I mean an ontological mode of relating to a subject through a degree of opacity. The subject is not at a distance, not exactly, nor are they entirely anonymous. Narrative darkness instead situates a subject that often goes overlooked—a space in which the communication, legibility, understandability of the subject goes unobserved. There can be freedom in these spaces of misrecognition, but also an imposed isolation. “That desire to be free, manifest as flight or escape,” as Fred Moten observes in Stolen Life, bears with it “an inability both to intend the law and intend its transgression …. The one who is defined by this double inability is, in a double sense, an outlaw.”

In the documentary The Shadow of the West, philosopher Edward Said speaks to the ways that Palestine has long held this space of misrecognition for the West, as observed in his book Orientalism (1978). Filmed five years after the book’s publication, the documentary reflects on representations of “the East,” addressing the history of Western artists, writers, scholars, and musicians attempting to capture the region through derisive and fetishized representations. Depictions of the Arab world tend to collapse or erase complex historical, social, political, and economic practices that have existed there for millennia. These portrayals, Said argues, are inextricably tied to the spread of European imperial forces throughout the Levant, beginning with France and Great Britain in the early 19th century. Stereotypical portrayals of Eastern subjects—from the violent to the oversexualized, the servile to the morally deficient—are a Western invention, a contradistinction fabricated as a foil to the West’s own distorted self-perception. Reflecting both obsession and convulsion, they mirror the racist ideologies and deep-seated prejudices undergirding the construction of Western exceptionalism.

Edward Said, The Shadow of the West (screenshot), 1983, documentary, 53 minutes [courtesy of YouTube]

Edward Said, The Shadow of the West (screenshot), 1983, documentary, 53 minutes [courtesy of YouTube]

Said refers, in The Shadow of the West, to “the Orient,” including the relatively nascent state of Israel as “an annex of Europe,” a nation ostensibly created as a haven for Jewish people amid rising anti-Semitism in Europe and now acts as a surrogate power structure of Western influence and ideologies seeking Eastern control. 1 The creation of Israel, in 1948, was followed almost immediately by the establishment of occupier settlements in Palestinian Territory, in which Palestinians were dispossessed of their homes and land, and forced to move into the areas now known as Gaza and the West Bank, as well as neighboring countries. In carving out the Arab world, Western powers furthered divisions within the region, thereby creating factions, schisms, and distortions along newly enforced borders. The creation of Israel depended—in the words of Ibrahim Abu-Lughod being interviewed by Said—on the “deliberate misunderstanding,” or lack of acknowledgment, of the Palestinian people, and on the region’s portrayal as an empty space, absent its own culture or history. Palestine became a space of conjecture by the West, subjected to its whims and projections—where misrecognition breeds exile, and exile breeds escape. In a land marked by dispossession and division, the question becomes who and what persists.

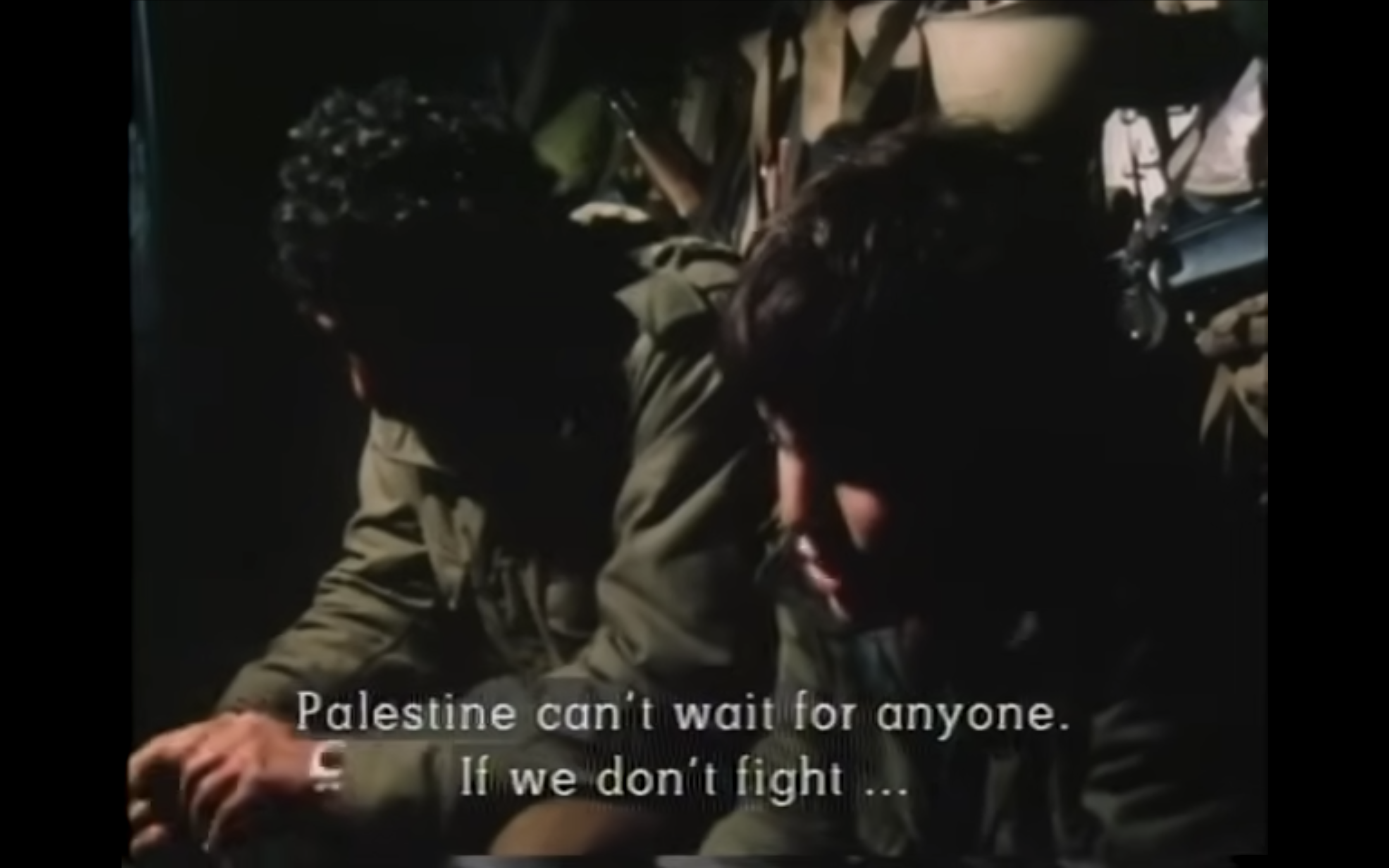

Throughout her practice, Palestinian artist Emily Jacir contends with this question. Working in film, photography, installation, performance, text, and sound, Jacir probes histories of movement, migration, exile, and the political, economic, or ecological factors that regulate them in Palestine and elsewhere. Her 2019 film letter to a friend confronts what Said refers to in misunderstandings of the East—how Western politicians, media, and even citizens consciously and unconsciously refuse to situate the East with any sort of specificity. Jacir’s film deliberately works against misrecognition by combining elements of documentary and speculation.

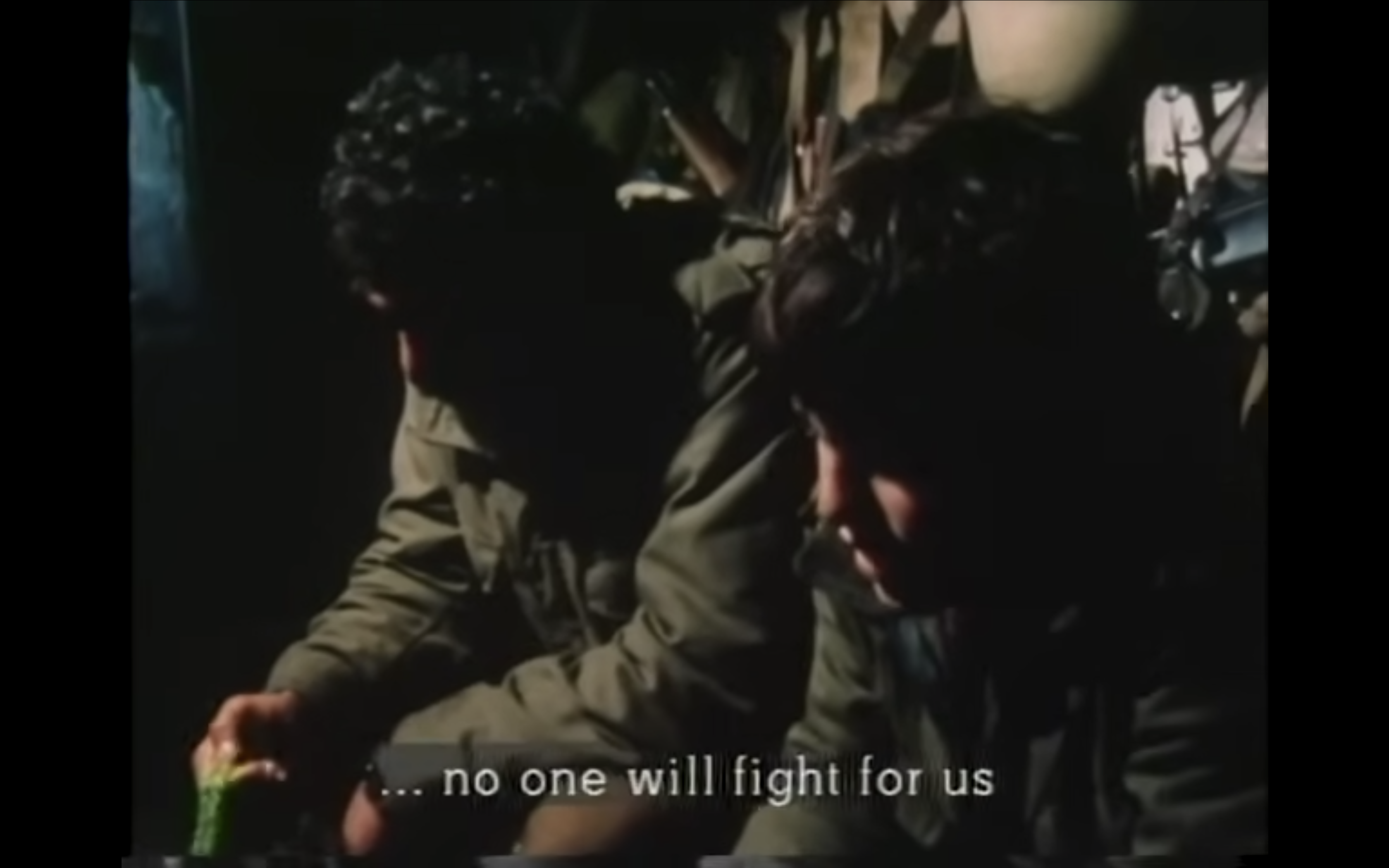

The film begins with a voiceover, as Jacir reads a letter written to her friend Eyal Weizman—an Israeli architect and founder-director of the research group Forensic Architecture. She writes to Weizman on April 11, 2019, which she describes as a calm day on her street, but she’s weary of how long the peace will last, given Israel’s aggressions. At Weizman’s request, Jacir had previously sent images of the thousands of teargas canisters littering the front of her home. From these images, Weizman identifies the Triple-Chaser, a brand of tear gas that divides into three pieces, making it difficult to throw back once deployed. The documented effects of the Triple-Chaser, Jacir reports, include “losses of consciousness, miscarriages, trouble breathing, asthma, coughing, dizziness, rashes, severe pain, headaches, and more.” Another friend, artist Michael Rakowitz, sends her a listing for the canister from a defense technology website. Jacir finds one of the three pieces, but the other two remain missing among the thousands of broken canisters scattered around her garden.

The Triple-Chaser has been used against civilians in Gaza and the West Bank by the Israeli Security Forces (a group that includes the IDF) and along the US–Mexico border by US soldiers. According to a 2017 study by the UC Berkeley School of Law, the Aida refugee camp, which is just 500 meters from Jacir’s home, is the most teargassed area in the world. But, as Jacir notes, the study and others like it often fail to acknowledge how that gas affects both the camp and non-camp communities. “I’m not sure if it is because they cannot tell the difference,” she tells Weizman, “or maybe they think everywhere is camp, or maybe it is simply not sexy to mention houses which are not part of a refugee camp. Yet, in all the pictures and videos of documentation of the exposure, it’s always of my street and of my house.”

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser, 2019, documentary, 10:35 [courtesy of YouTube]

With a series of annotated maps, found photographs, new and archival footage, and long tracking shots of the Bethlehem cityscape, Jacir details the history of the location where her family home is situated. She shows a picture, from 1931, of the Hebron Road, which runs north to Jerusalem and south to Bethlehem. Her home sits just past the road’s fork. Down the road is Rachel’s Tomb, a site revered by Christian, Muslim, and Jewish women as the burial place of the Biblical matriarch Rachel. After the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993,2 Israel walled off the tomb and laid sole claim to the site’s cultural significance.3 A Palestinian Authority checkpoint was built just outside Jacir’s front door around the same time; she takes a video of it, remarking on how the men stationed there have no real authority but sit surveilling her home day and night, both menacing and ineffectual.

Dar Jacir (Jacir House) was built in the 1880s by the artist’s grandfather, Yusuf Ibrahim Jacir, the town’s mukhtar (registrar) and trustee. At the entrance, a pale-yellow iron gate and tall trees nestled in the surrounding garden shroud a stone walkway, terrace, and stately facade. Yusuf’s son Suleiman Jacir, a two-time mayor of Bethlehem, was once a successful merchant who, from 1910 to 1914, oversaw the construction of a palace next door to the family’s main home. Jacir Palace housed the extended family until they went bankrupt in 1929. Jacir shares a series of photos from that time, and she juxtaposes her own photos, taken from the same angle, near the palace, which is now a hotel and event venue. Her home is buttressed by ‘Azza camp, across the street to the east, and Aida camp to the northwest. ‘Azza camp is the smallest of the 59 refugee camps. Jacir’s father worked at both camps in the 1960s.

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, 2019, documentary, 43 minutes [©Emily Jacir; courtesy of the artist]

She relates her home geographically to Israel’s apartheid wall—a 440-mile barrier that separates Israeli-occupied land from the West Bank.4 The wall is more than twice as long as the Green Line, the de facto border of Israel following the Nakba and the Six-Day War in 1967, after which the line demarcated territories captured, and now occupied, by Israel: East Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza, and Golan Heights in Syria. Diverging from an already unnatural boundary, the wall devours the land surrounding it. Jacir shows Weizman early photographs of the wall, before it was covered in graffiti. It noticeably cuts directly through the neighborhood, not in a straight line, but as a jagged labyrinth.5 She describes walking to a friend’s nearby home, which is accessible now only via the mazelike border imposed by the wall. As Jacir observes, “The wall does not separate us from Israel, but rather separates us from ourselves. From each other.”

Jacir tells Weizman that the purpose of her letter is to formally ask Forensic Architecture to “conduct an investigation before a crime has been committed—before the incident occurs.” The subject of the investigation—Jacir’s family home in Bethlehem—has long borne witness to the IDF’s targeted aggression in the West Bank, which historically, and at present, results in the ongoing dispossession of Palestinian homes for the construction of Israeli settlements. In revealing her findings, she hopes to enlist Forensic Architecture to gather enough evidence for future legal proceedings.

Forensic Architecture (FA) was founded by Weizman in 2010 at Goldsmiths, University of London. The group uses architectural methods and technologies to investigate sites of state-sanctioned human rights violations, environmental destruction, and other abuses of international law around the world. Their techniques encompass site visits, ground-penetrating radar, digital model creation, audio analysis, and witness testimony. FA works with interdisciplinary investigators—including journalists, artists, academics, filmmakers, software developers, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists—and often works directly with activist groups to present findings in exhibitions and in international courts. One of FA’s earliest well-known cases involved the killing of Nadeem Nawara, a 17-year-old Palestinian boy, and 16-year-old Mohammad Mahmoud Odeh Salameh, who were both fatally shot during a protest on Nakba Day, outside the city of Beitunia, in the West Bank.6 Ben Deri, the Israeli border officer who shot Nawara, was initially charged with manslaughter, but FA’s investigation and resulting film asserted that the officer should have been tried for murder, as both boys were shot while posing no threat to officers. Working with artist and audio investigator Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who also narrates the film, the group analyzed the security and TV video footage, along with still shots, to determine the aural signatures of the gunshots, which were identified as live rounds, thus contradicting the findings of the military’s investigation and its claim that the soldiers were firing rubber bullets.

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser, 2019, documentary, 10:35 [courtesy of Forensic Architecture]

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser, 2019, documentary, 10:35 [courtesy of YouTube]

Forensic Architecture’s ongoing research includes the case against Israel’s apartheid—the construction of its segregating wall, its stronghold over building and cultivation permits, and its ecocide in Gaza and the West Bank,7 all of which constitute forms of architectural violence against both the people and the land.8 Israel commits these acts by both legal and permissively illegal means. The Ottoman Land Law of 1858, for example, was established during a period of agrarian reform to encourage farmers to continuously cultivate their land. If, after several years, the land was uncultivated, ownership of it would fall to the Ottoman state. This law has been instrumentalized by Israel; the government controls rights to cultivation and frequently denies permit requests by Palestinians, a loophole that has allowed the settler government to appropriate “uncultivated” land. Weizman observes: “Here, as in other incidents throughout the occupation, the law did not prevent violations, it simply became a tactical tool for regulating them and giving them a cloak of legitimacy.”9

Forensic Architecture operates between forensics, or what they call “counterforensics,” and architectural and aesthetic practices. They refer to this space—one of narrative darkness—as the “threshold of detectability,” where things “hover between being identifiable and not [where] both the surface of the negative and that of the thing it represents must be studied as both material objects and as media representations.”10 Although the group employs forensics linguistically and procedurally, it doesn’t discount witness testimony, often working at sites where evidence is concealed or illegally withheld. For this reason, FA chooses counter-forensics as its working mode to push against the legal, political, militaristic co-option of criminal investigations—what it terms the “forensic gaze.”11

Jacir’s letter to a friend both complicates and contends with the “forensic gaze,” which we might call an extension of the ever-present Western gaze—the subjugating act of looking that scholars such as Said illuminated. She recalls that her parents never spoke about the 1967 war, but that she later discovered a letter written by her mother to her best friend that detailed her experience.12 Such close conversations inspired the material dimensions of the film. Through her careful situating of her home as both site and subject, as witness to a violently shifting geographical landscape, Jacir manifests her own “oppositional gaze,” as defined by bell hooks.13 This form of the gaze doesn’t necessarily grant agency to the subject or an escape from a marginal position but rather exposes the reflexivity of looking, thereby recognizing the multiplicity of gazes. She doesn’t make a spectacle of the violence occurring mere feet from her front door. She instead documents the daily, pervasive crimes, the “slow violence”14 endured by the community. In one sequence, Jacir shows a series of photographs and video taken by her friend Rehab on the day she was shot by an IDF soldier on Jacir’s street. The imagery is hazy, muddled by clouds of tear gas, but the distinct image of the solider who shot Rehab is clear. It is not an explicitly, visibly violent scene, but the casualness with which Jacir’s friend is shot, while in the process of documenting, speaks to the intent of silencing those who would bear witness to the crime before it has been committed. It simultaneously demonstrates the stakes of Jacir’s request to Weizman specifically—as an Israeli investigator born into the cultural inheritance of a settler colonial regime, as well as a friend.

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser, 2019, documentary, 10:35 [courtesy of YouTube]

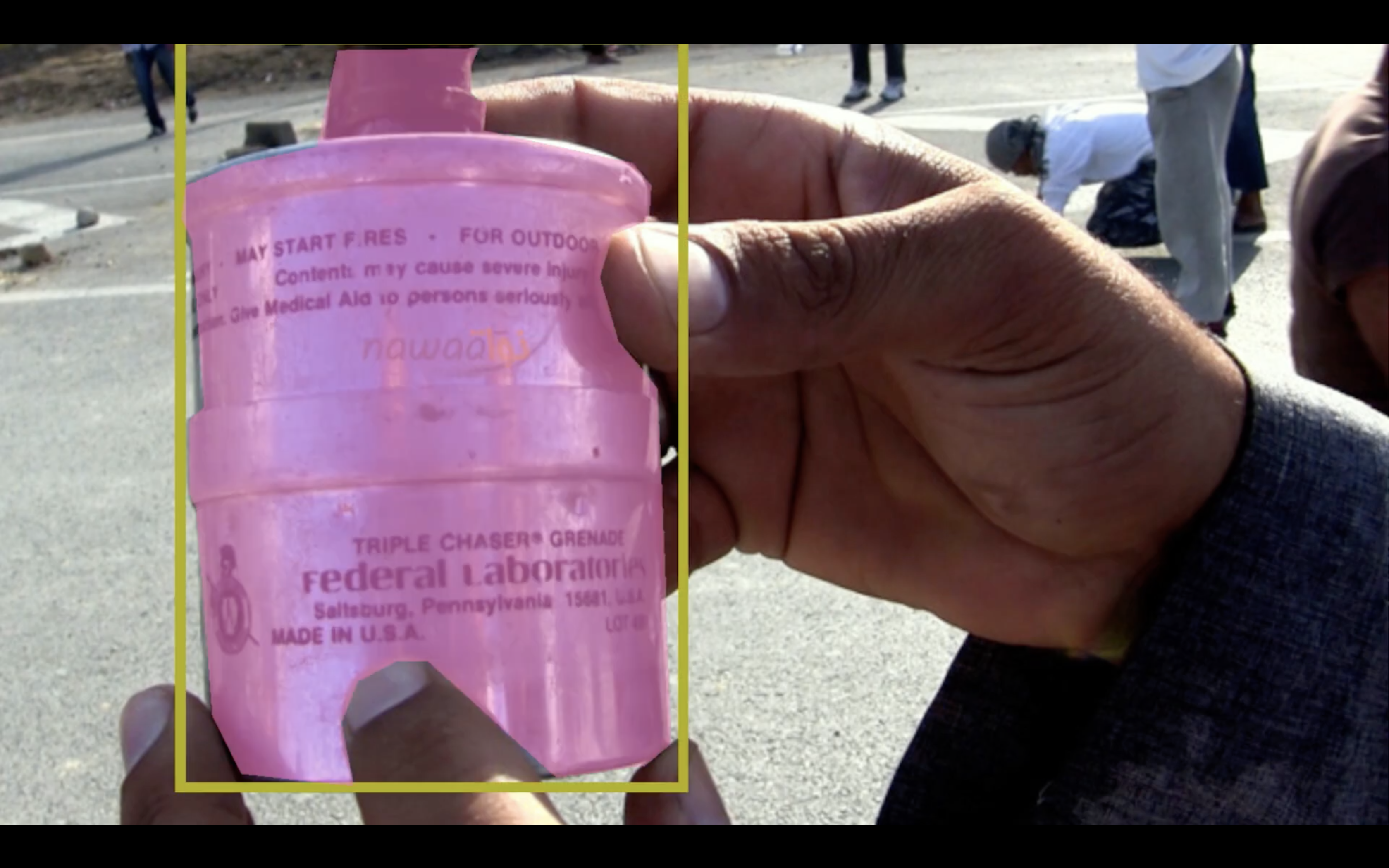

Weizman refers to Triple-Chaser, the variety of teargas canister that Jacir found in her garden, as “the most evil tear gas canister.” It came into the public eye during the 2019 Whitney Biennial, when Forensic Architecture’s documentary film Triple-Chaser exposed the Whitney Museum’s then vice chairman, Warren Kanders’ complicity in the manufacturing of that gas, via his weapons company Safariland. The film, directed by Laura Poitras and narrated by David Byrne, documents the process by which FA gathered data on the use of Triple-Chaser. Volunteers in Bethlehem, Tijuana, and other sites gathered empty canisters. They were then scanned and digitized. Using images of the tear gas from the Safariland product catalogue, Forensic Architecture collaborated with NVIDIA, a computing technology company and artificial intelligence developer, to create “synthetic images.” These images were then used to form an online repository to identify other, real appearances of the canisters in civilian zones.15

Many people are by now familiar with tactics used by the IDF—tear gas, drone attacks, white phosphorus—seen in images of the IDF’s brutality after Hamas’ October 7, 2023 attack. What Forensic Architecture uncovered through its multiple probes of the occupation is the enormity of the blatant obliteration of human rights that settler forces laid on Palestinian civilians before and since October 7. Kanders eventually resigned from the museum’s board, following months of protests catalyzed by FA’s Triple-Chaser. The controversy sparked an unprecedented line of questioning around funding sources for museums and other nonprofit arts organizations. In the aftermath of the biennial and Kanders’ exit, this questioning quieted, but the discourse has, in some ways, resurged amid renewed calls for divestment from Israeli and US–military funds as the genocide in Gaza continues to unfold.

Decolonize this place protests at Whitney Museum, 2019 [photo: Perimeander; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Jacir explains that her anticipation of an impending crime stems from the settlers’ ever-present, intergenerational encroachment. She states that at the time her film was shot, there were 18 Israeli settlements, with more than 100,000 occupants, built around Bethlehem.16 The settlements—which the government built, and largely subsidizes, for Israeli civilians and an international Jewish community—are in direct violation of international law. “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies,” Jacir quotes from the Fourth Geneva Convention.17 Yet, these settlements continue to expand and divide the populace along religious, ethnic, and racial lines. Israel’s occupation, with settlements linked by segregated roads and military checkpoints, has reduced Bethlehem’s footprint by almost 90% as of 2024. The events of October 7 precipitated the largest seizure of Palestinian land since the Oslo Accords of 1993.18 “We are now surrounded on all sides.”

Forensic Architecture, Triple Chaser, 2019, documentary, 10:35 [courtesy of YouTube]

letter to a friend bears the aesthetic markers of documentary, but it is, in many ways, freed from the limitations imposed upon the genre.19 Documentary in the style of cinema verité, an observational mode depicting real, everyday events, evolved in the 1960s. At the time, documentary filmmaking often relied on observational, “fly on the wall” tactics to portray reality or truth. Cinema verité is characterized by the acknowledgment of the camera’s presence (usually in the form of a handheld device), and by the director’s role in pushing an action forward. This technique was seen as a foil to propagandistic war-era filmmaking. As Weizman observes, reflecting on FA’s work:

Human-rights sensibilities co-evolved with artistic and documentary representation. An entire cultural/intellectual apparatus became attuned to the complexity of trauma and memory through theory, art, and psychoanalysis. For the human-rights movement, testimony was not only an epistemological necessity—activists didn’t speak to people just in order to know what happened. There was much more going on in that encounter: It was a manifestation of compassion that posed individual voices against the arbitrariness of authoritarian states. The so-called era of the witness reshaped sensibilities but also ended up individuating and thus depoliticizing collective situations.20

Fugitive documentary might not claim the objectivity of the filmmaker (if such objectivity can even exist), but it does insist upon the subject’s experience apart from that of the filmmaker, thus forming an anti-auteur approach that goes beyond the notion of simply “bearing witness.” In Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman critiques our capacity as witnesses—our proclivity toward acts of looking at scenes of “spectacular violence”21—as a form of documentation: “Are we witnesses who confirm the truth of what happened in the face of the world-destroying capacities of pain…Or are we voyeurs fascinated with and repelled by exhibitions of terror and sufferance? What does the exposure of the violated body yield?”22 In letter to a friend, we follow Jacir as she reconstructs the history of her neighborhood. At times, her narration overlaps with synchronous audio of her counting paces, of humming cicadas, or of army vehicles lumbering past. As she reports on her findings, on the myriad crimes before the crime, the distinct feeling arises that we, the viewers, are not her primary audience. Her voice is somber—not performed—in the way you speak to someone who’s familiar to you. Moments of dry humor and possible inside jokes intercut footage of tear gas blanketing the street. Much of the footage seems impossible for one person to capture, let alone for another to comprehend. In showing us these images, Jacir implicates us along with Weizman in the act of looking—the viewer sees what the narrator sees: detailed documentation of past, present, and future injustices, observed through an intimate, open dialogue.

Michael Rakowitz has observed that “Emily’s work operates as an invitation,”23 a welcoming gesture that occupies a space above and beyond language. Her dialogue with Weizman ultimately speaks to a particular form of grief—grieving that which has not yet happened, and yet continuously happens amid atemporal layers of collective loss. letter to a friend is both an inward and outward gesture—a record, diaristic and introspective in tone, exposed as an act against an enforced mentality of separation. Jacir and Weizman/Forensic Architecture operate at different vantage points and levels of detectability, but in their respective praxes, narrative darkness unveils the contradictions intrinsic to the notion of unseeability by reconstructing the subaltern event. When acts of looking, of bearing witness, of documentation, are not enough, narrative darkness marks an ontological turn toward fugitivity. “That desire to be free, manifest as flight or escape,”24 as expressed through the open letter, transforms an overlooked narrative into a story of many.

References

| ↑1 | The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 allowed the United Kingdom and France to partition the Ottoman Empire after the latter’s dissolution post-World War I, thus granting these nations sovereignty over the Arabian Peninsula and what is today Israel, Palestine, Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon. A year later, the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, which promised away the area now known as Palestine to create a “national home for the Jewish people.”[1] These agreements paved the way for the eventual creation of the state of Israel in 1948, a year marked by the forced removal and ethnic cleansing of Palestinian people. This event is referred to by Palestinians as the Nakba, which is Arabic for catastrophe. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Oslo Accords comprise two agreements between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO, founded 1964), under the administrations of PLO chairman Yasser Arafat, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, and US president Bill Clinton. The accords aimed for peaceful resolution of the “Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” They officially recognize the state of Israel, and the PLO as the official representative of Palestine, without recognizing the Palestinian state itself. The accords initiated the creation of the Palestinian National Authority, which ostensibly grants self-governance over Gaza and the West Bank. Many Palestinians remain opposed the accords for not addressing Palestine’s statehood, the expansion of settlements, or military presence in Gaza and the West Bank. The accords likewise remain opposed by many Israelis for not addressing the country’s security concerns and attacks along its prescribed borders. |

| ↑3 | In 2010, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu added the tomb to the country’s national heritage list. UNESCO urged Israel to remove the site from its list, as Jacir’s film explains, stating that it was “an integral part of the occupied Palestinian territories.” UNESCO passed a resolution that acknowledged both the Jewish and Islamic significance of the site, with 44 countries supporting it, 12 abstaining, and only the United States voting to oppose. The wall built around the tomb in 2002 still stands. |

| ↑4 | The Israeli West Bank barrier was built during the Second Intifada (September 2000–February 2005). The wall was built after a wave of attacks in Israel, initially to curtail further violence in the region, but now it is widely recognized as an apartheid wall that segregates Israelis from Palestinians. See B’Tselem, “The Separation Barrier,” November 11, 2017. https://www.btselem.org/separation_barrier. |

| ↑5 | For more on forms of agricultural resistance in Palestine, see artist Jumana Manna’s documentary Foragers (2022). https://cargocollective.com/jumanamanna/Foragers. |

| ↑6 | See Robert Mackey, “Video Analysis of Fatal West Bank Shooting Said to Implicate Israeli Officer,” New York Times, November 24, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/25/world/middleeast/video-analysis-of-fatal-west-bank-shooting-said-to-implicate-israeli-officer.html; for Forensic Architecture’s project and film, see “The Killing of Nadeem Nawara and Mohammad Abu Daher” https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/the-killing-of-nadeem-nawara-and-mohammed-abu-daher |

| ↑7 | Forensic Architecture, “Herbicidal Warfare in Gaza,” July 19, 2019, https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/herbicidal-warfare-in-gaza. See also Rob Goyanes, “The Ecological War on Gaza,” Jewish Currents, September 9, 2019, https://jewishcurrents.org/the-ecological-war-on-gaza |

| ↑8 | Yve-Alain Bois and Hal Foster, “On Forensic Architecture: A Conversation with Eyal Weizman,” October 156 (Spring 2016): 118. |

| ↑9 | Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (London and New York: Verso Books, 2007), 118. See also Peace Now, “What is a declaration of state land?” September 8, 2014. https://peacenow.org.il/en/what-is-a-declaration-of-state-land |

| ↑10 | Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 20. |

| ↑11 | Ibid, 9. |

| ↑12 | “Revisiting Studies into Darkness: Conversations on Freedom of Speech—Part II: Open Letter in the Dark, with Emily Jacir, Michael Rakowitz, and Jill H. Casid,” Brooklyn Rail and the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, May 29, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TW1QDl3gjsw |

| ↑13 | bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectator,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press, 1992), 115–131. |

| ↑14 | “On Forensic Architecture: A Conversation with Eyal Weizman,” 118. |

| ↑15 | See Nicholas Gamso, “Truth, Politics, Disintegration: Forensic Architecture at the Whitney,” World Records 4, article 9 (2020). |

| ↑16 | Later in the film, Jacir states that there are 21 settlements, underscoring the rapid progression of the colonial occupation. On August 15, 2024, Israel approved a new illegal settlement on a UNESCO World Heritage Site near Bethlehem, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/8/15/israel-approves-new-illegal-settlement-on-unesco-site-near-bethlehem |

| ↑17 | [2] “Article 49—Deportations, transfers, evacuations,” in Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, August 12, 1949, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gciv-1949/article-49 |

| ↑18 | Peace Now, “The Government Declares 12,000 Dunams in the Jordan Valley as State Lands,” July 3, 2024, https://peacenow.org.il/en/state-land-declaration-12000-dunams |

| ↑19 | Documentary film theorist Jonathan Kahana addressed such limitations in his discussion of the work of historian-philosopher Hannah Arendt, particularly her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). The book focuses on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the top officials of the Nazi party and an orchestrator of the Holocaust. Arendt, who fled Germany before the Nazis’ rise to power and was present at Eichmann’s trial, was criticized for her assertion of the “banality” of Eichmann’s actions, which, according to Arendt, displayed neither malice nor contempt but rather an internalized rationalization of the Nazi ideology. Kahana writes that, in the early 60s, “among documentary critics and producers alike, an ideological distinction establishes itself, between verité́ and direct forms of documentary and all documentary styles not liberated by embodied acts of eye- (and ear-) witness.” Jonathan Kahana, “Arendt in Jerusalem: Documentary, Theatricality, and Irony,” World Records 4, article 5 (2020). |

| ↑20 | “On Forensic Architecture: A Conversation with Eyal Weizman,” 120–121. |

| ↑21 | Rayya El Zein similarly makes a thoughtful argument for the ways that Hartman’s work resonates with the documentation of violence against both Black and Palestinian people. See “To Have Many Returns: Loss in the Presence of Others,” World Records 4, article 4 (2020). https://worldrecordsjournal.org/to-have-many-returns-loss-in-the-presence-of-others/#source{6}. |

| ↑22 | Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self- Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 3–4. |

| ↑23 | “Open Letter in the Dark.” |

| ↑24 | Moten. |