Tobias Wallisser: Expo 2020, LAVA, and the Future

Energy Storage Tower in Heidelberg © LAVA

Share:

Once the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture (LAVA) won the Germany Pavilion at Expo 2020 in Dubai in collaboration with Cologne-based Live Communications Agency, facts and fiction, and Swiss construction company Adunic, LAVA went to work on the theme, Connecting Minds, Creating the Future, with the zeal evident in this relatively youthful architecture firm’s desire to rebrand the notion of Made in Germany. Located inside the Sustainability District of the Expo, the Germany Pavilion will address the topic of our sustainable future, a theme that runs through contemporary German policymaking, business practice, social-cultural agendas, and national identity but that extends more and more urgently to all people and places.

Chris Bosse, Alexander Rieck, and Tobias Wallisser founded LAVA in 2007 as a network of offices in Sydney, Stuttgart, and Berlin to form a collective vision of possible futures. As an innovator in built environment technology with collective roots in Frei Otto’s concepts of lightweight structures, LAVA considers every project a new opportunity for research and exploration of the unusual; the firm pushes the boundaries of tradition and bends structures to the will of digital form-finding that responds to human intelligence.

Caia Hagel sat down with the Germany Pavilion project’s lead, Tobias Wallisser, to discuss LAVA’s big ideas as they move from concept to construction.

Caia Hagel: How do the German Pavilion’s legacy and Expo 2020’s mandate as a festival of human ingenuity coalesce to create the perfect storm for LAVA?

Tobias Wallisser: Germany has a history of thought-provoking architecture. Mies van der Rohe did the German Pavilion at Expo ’29 in Barcelona, Frei Otto at Montreal’s Expo ’67. These were extraordinary, iconic buildings, but no one talks about what happened inside them. Architecture isn’t purely a façade. Today, buildings really ask for interaction and an integration of their disciplines, materials, and agendas. We are using that challenge to push boundaries forward with this project that will illuminate Germany for the expected three million visitors from around the world.

At LAVA, our architecture goal is to create an ecosystem through constructing a much more natural habitat than the engineered surrounding. We studied together in Stuttgart under the influence of Frei Otto’s ideals and [had] our different experiences—Chris [Bosse, a key designer of the Water Cube at the 2008 Beijing Olympics], who uses the latest digital fabrication technologies to mimic the geometries of nature in buildings and their skins; Alexander [Rieck, also a senior researcher] at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO], whose virtual reality research makes architectural dreams come true, and myself, who invents space typology to suit the function of a building so the parts form one entity that flows. The ingenuity for us, in collaboration with facts and fiction, is going beyond the summary of square meters and the briefing by the client—to be inspired by nature to invent a new built landscape that is identified by feelings.

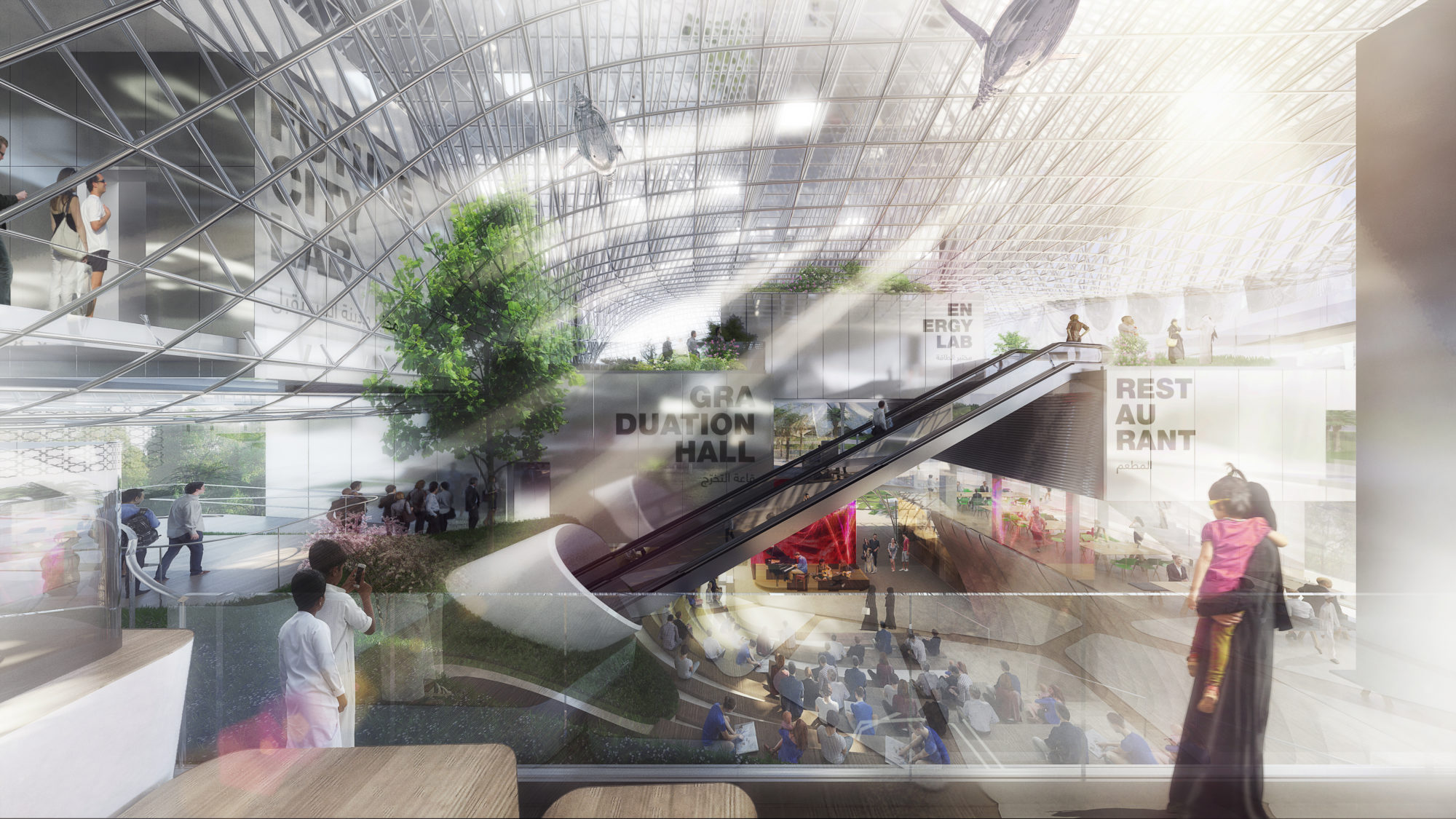

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY: Restaurant [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: What kind of feelings?

TW: The German Pavilion is a temporary structure. It’s [up for only] six months. But in terms of building regulations, like fire and security, the same rules apply as for long-standing structures. So we had a lot of discussion about how to be lightweight, how to use the minimum amount of material to create a maximum volume, and how to have separate modules that meet together in the middle of an open atrium. What we’ve come to is a very porous structure. It’s very open. We think Germany is still an open country. So this landscape is about open feelings, coming together and feeling open.

CH: It’s also horizontal. At 4,500 square meters it is going to be among the largest buildings at the expo, so large that it’s being called a campus.

TW: The building is actually a leitmotif. The metaphor is here on our German Campus we will feature entertaining education about many aspects of sustainability. This will include how to envision a better future through three labs that feature future energy, future cities, and biodiversity. Each theme is portrayed in one big scene where the spatial experience is closely related to the exhibits and to opportunities for interaction. We are hoping that bringing people together to play games and learn about aspects of our topics in a leisurely, playful way will be a good experience.

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY: Side View [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: That’s a new angle. Germans aren’t known for their playfulness.

TW: I love living in Germany, but it would be nice to have more happy, playful aspects visible in German culture. Germany is a federal state, so our pavilion statement cannot be a one-liner. There are too many agencies involved, and you have to represent them all. This creates a displaced diversity that is unified in diversity. Our campus metaphor is quite strong because rather than grouping things by where someone or something comes from in Germany, we have a multiplicity of themes and spatial situations that allow everyone to bring their content and integrate [it] into a larger whole. That’s our invention. We have space and exhibits and a new way of bringing it all together that we hope will be fun.

CH: You also have IAMU [I-am-you], a world-first intelligence assistance system that brings a social aspect to the structure that’s very contemporary.

TW: Yes, the IAMU intelligent name tag technology, developed by our partners facts and fiction, is like a fourth dimension of the pavilion. It will be an “invisible companion to visitors” that will be guiding them through the multistory campus, the three labs, and the leisure areas. It’s not gendered or European. It’s an artificial intelligence with proven technology. Warehouses use it, but it has not been used in social situations or exhibition contexts to the extent that we’re using it. When visitors give information about themselves, the exhibition interacts with them, addresses them in their native language, and organizes them into group activities. An exhibit might ask a visitor to play a game and suggest, “Why don’t you ask these three people behind you to join?”

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY: Exhibition, “Future City Lab” [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: Is that uncanny or are you thinking more like Spike Jonze’s Her?

TW: That would be too much like Big Brother. It would be horrible if there was a centralized intelligence. IAMU records where you spend time and how much time you spend, not to control you or to make the next pavilion an efficient machine, just for us to note. IAMU only knows what you tell it. You tell it things only while you are at the German Pavilion. This personalized information is what makes it possible to interact with the exhibits, the material, and other visitors. IAMU can record feedback on topics as well. This gives visitors the chance to intermingle and put their opinions in perspective with others. IAMU needs to be a very robust device, almost like a phone which, like a phone, we want to work and look beautiful. Imagine that you were able to walk through your phone, see it from the inside, within a space and device that knows a little bit about your needs, tries to connect you to other people and offers you the possibility to learn something. This is IAMU.

CH: That sounds nice. I thought it was disappointing in Her [that the relationship between Theodore, the human, and Samantha, the Scarlett Johansson-voiced Operating System, was so short lived and discouraging].

TW: [laughs] I’m not sure that anyone will fall in love with IAMU. There won’t be kissing, either, in our pavilion in Dubai. Our aim is to bring people together in other ways. Maybe you come to the German Pavilion and you think, I don’t believe in climate change, and you discover that you’re not the only one. We are learning in Germany that the best way to deal with right-wing populist ideas is to create dialogue with them. In the same way, if we want to do anything about climate change, it’s important to talk to people about it, hear all opinions, be open to all ideas and dialogues.

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY at night: Front View [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: Are you referencing the social questions in Germany right now, particularly around how to successfully integrate diversity?

TW: Germany on that level is not as diverse as it could be. We have had a lot of national discussions about this topic since the influx of immigrants from the Middle East, and especially since soccer star Mesut Özil [born in Germany and of Turkish descent] resigned from the national soccer team in July [Özil resigned, citing German disrespect and racism, and stating, “I am German when we win and I am an immigrant when we lose”]. Strong debates over immigration and integration are necessary everywhere. It begins with discussion, knowing that a good and just vision is not always easy to fulfill.

CH: Is it utopian then to present this playful artificial integration as a goal if, in reality, it’s so much more complex and perhaps unachievable a process, at least in the near future?

TW: I don’t think so. How many people meet their partner through Tinder? That was hard work in a bar 20 years ago, and the people you could meet were far less in number or diversity. Change starts with very simple elements—in this case, with a pavilion that has a more controlled environment where people can express themselves openly and try to respect and understand each other’s opinions. With digital help, we are hoping it will be easier to trigger that.

How we connect with artificial intelligence is another component. We are also looking at the interaction between people and the environments we create. Attaining sustainability will require that our environments be much more adaptable and changeable. I’m sitting in a hotel room right now where the [air conditioner] is on when it’s cold out; it’s not intelligent, and I’m paying for a large room that I don’t use during the day. The dream is that buildings can be reconfigured, optimized, and made intelligent, so they can adapt to changing users, environments, temperatures, acoustics, light. Even the hardware of a building can create a journey. This is part of the reality that is unfolding.

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY: Atrium [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: Do you feel that video gaming is having an impact on reality too, in terms of what users expect from space, aesthetics, emotional experience, and connectivity?

TW: I admire Cedric Price’s Fun Palace and the idea of bringing people together with technology to provide augmented experiences. The Centre Pompidou was inspired by this notion of space. We have more and more possibilities to explore and expand on the intersections of the virtual and the real. Video games change perception. The virtual effects on the perception of the actual bring us to a new concept: what imitates what? Are we trying to imitate the world or are we imitating the virtual world?

CH: Are you getting at a new definition of architecture?

TW: I think architecture is a cultural discipline. It is a service that should strive to do something that has added value, something that makes people’s lives better, makes them think about something or puts a smile on their face. The German Pavilion officially represents Germany, so visitors should get a glimpse of how Germany wants to see itself—[as] a country that offers technology, that is trying to do the right things, be open, integrate, and give people opportunities to learn and to grow. It reflects our approach to dealing with sustainability, which isn’t just energy saving; it’s a new way of seeing the world of energy, mobility and bringing people together.

Architects don’t know everything, and we shouldn’t determine everything. We should be having exchanges with people who aren’t architects by providing options for them to choose from and allowing users to interact, determine the use of space, make sense of their experiences inside space, and ultimately impact their world. A diverse audience can find their own ways to interact with this building. Dubai is a young society compared to Germany, and it’s a digital society as well. So if we want to represent a country known for engineering, research, and innovation, we have to do something different, maybe even that bridges generations and can be re-imported to Germany.

We hope that people will leave our pavilion and think that was a great journey through relevant topics, and if we work together we can affect the future, together. It sounds naïve, but as banal as it is, it’s very important. Nothing will change if we develop the best devices and environments but nobody knows how to use them. We have to start with people. So we have high-tech and we also have low-tech. If IAMU doesn’t work, we have a biergarten with palm trees and no technology. Here you can put your devices away and just sit outside, drink beer, and have a basic experience that is part of the German lifestyle and just being in a body.

Digital rendering, The German Pavilion CAMPUS GERMANY: Side View [© 2018 by: LAVA/Facts&Fiction/Adunic]

CH: That sounds great, but what about Instagram and the Anthropocene?

TW: In Dubai every building tries to be more Instagrammable than the next, but inside they’re all the same. We live in the Anthropocene. Humankind has an impact on the planet. We should all be aware of that, and aware that we need to work together to create change and prevent the worst from happening. The German campus and IAMU hope to help visitors to discover the fact that, even if we have different backgrounds, we share more things than we are aware of. We are not alone, we are always part of a group, maybe different types of groups according to different topics, but still groups. If with this Expo 2020 German Pavilion we are able to create something that is memorable, provocative, and Instagrammable, we will achieve an iconic quality but also an affective experiential quality. Architecture should be that.

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Energy Structures” Spring/Summer 2019.

Caia Hagel is co-author of the groundbreaking book Girl Positive, and co-founding editor-in-chief of SOFA magazine. She speaks about art, design, fashion and the future at international events. Her presentation on selfies at Forum D’Avignon Paris contributed to a Bill of Digital Human Rights.