Tirzo Martha: Things in Perpetual Becoming

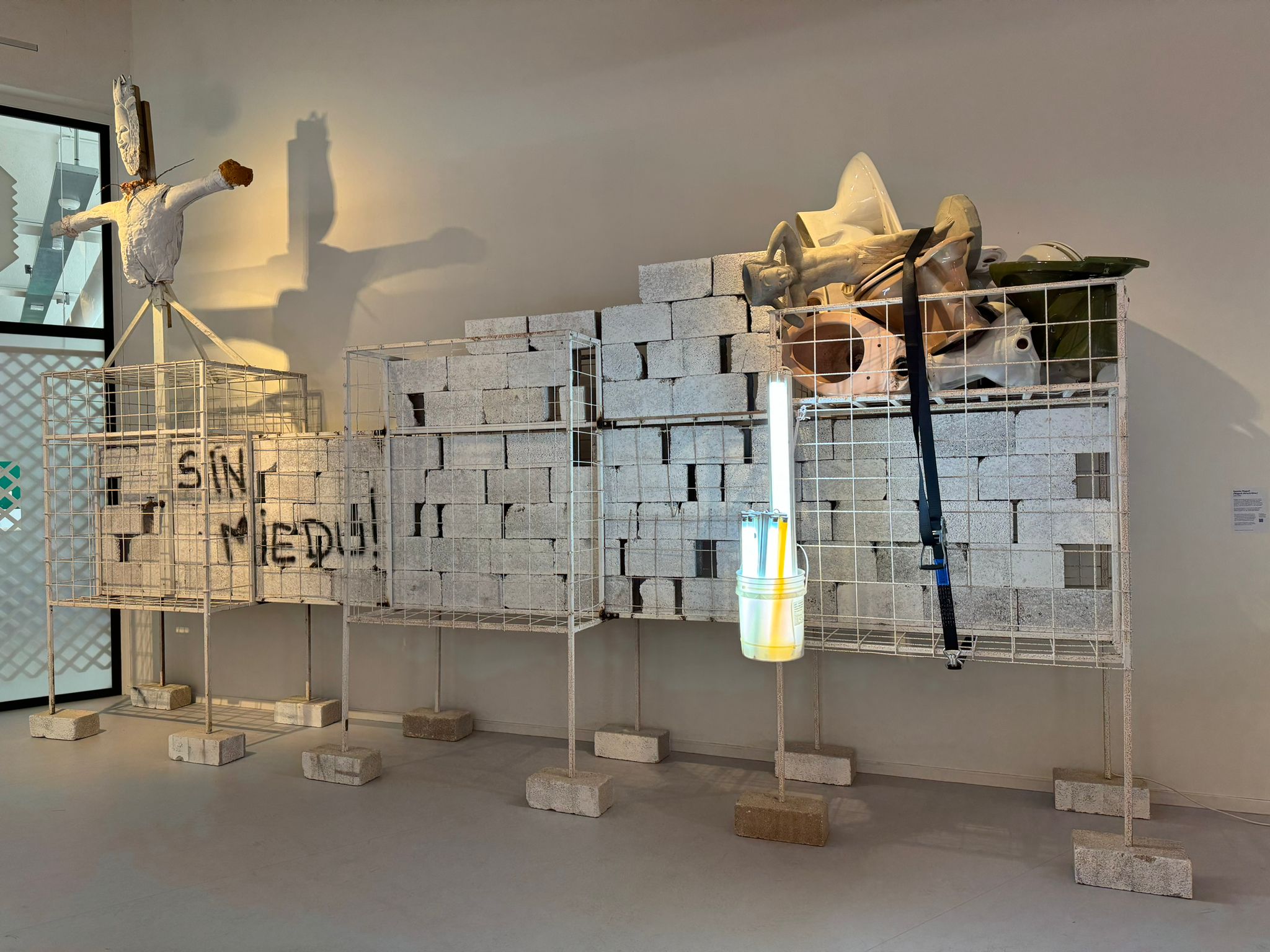

Tirzo Martha, untitled, installation view, 2022, [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Tirzo Martha is an artist based in Curaçao and the founder of Instituto Bueno Bista (IBB). I traveled to Curaçao in June 2023 to meet him and continue the research and writing I was doing about the island for my novel. IBB is a contemporary art center in Curaçao that offers a two–year art preparatory program to youth on the island who then go on to attend art school at the collegiate level in the Netherlands. IBB also hosts an artist residency that is open to international artists. While at IBB, I visited Tirzo Martha in his studio, which was the start of our conversation about his practice. This interview was conducted later, via Zoom, once I’d returned to the US.

Sherae Rimpsey: Hello, Tirzo! When I talked to you last, you were in São Paulo for Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil. What did you show there?

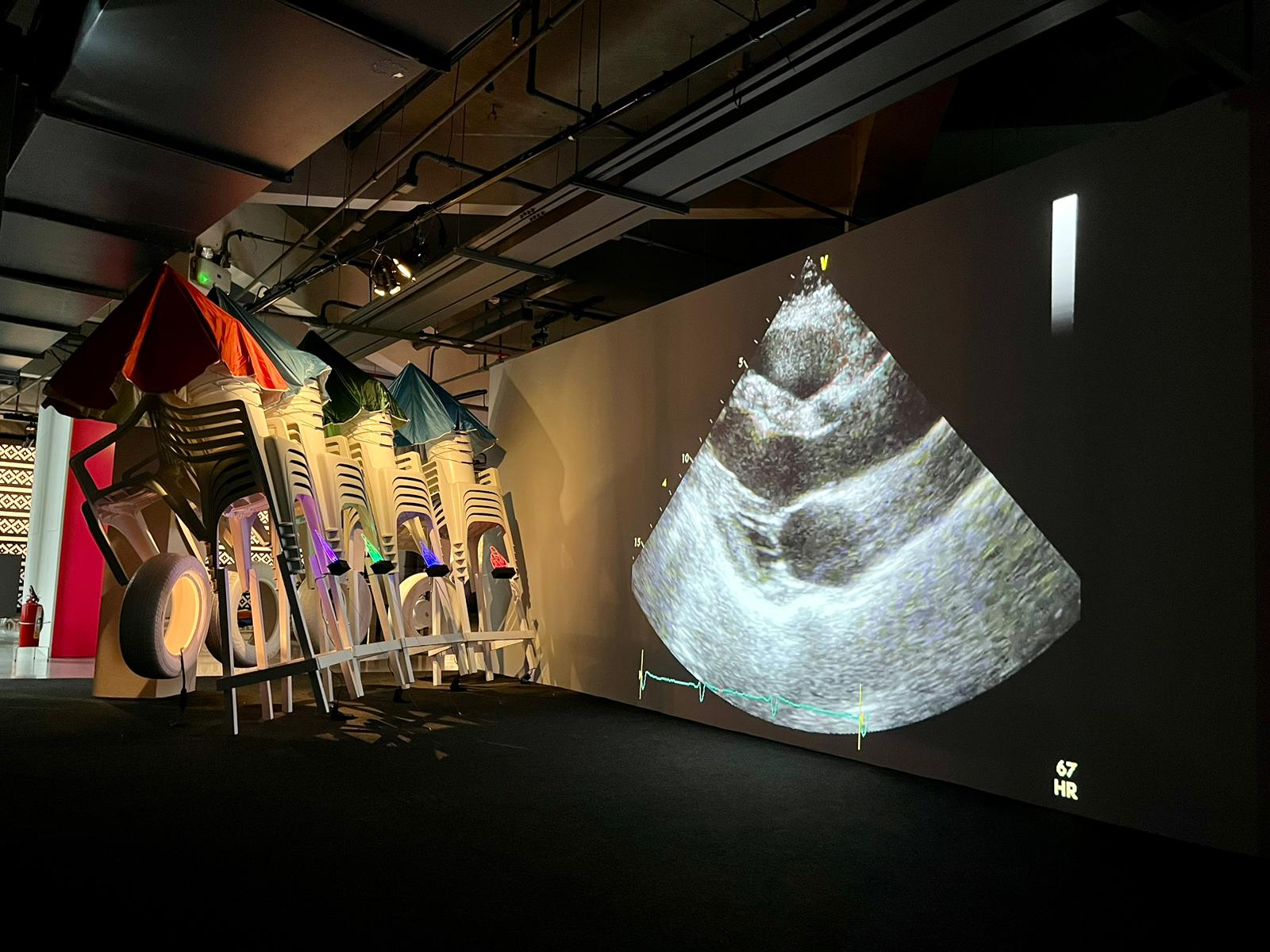

Tirzo Martha: This biennial was supposed to take place a few years ago, but because of the pandemic, they canceled it [then] and did it this year. I was asked to make an installation there, and I made this video installation. The title is Republic of the Caribbean. It is a work about when you have carnival here in the Caribbean. Most of the time, people along the roadsides—you know, the route where the Carnival is going to pass through—are building shacks, tents, and all these things, so they can [be] covered from the sun. And in a way, it’s like they build a new city. For me, it’s also like they build a new land—a totally new community. For me, this condition that they build has its own rule. They have their own conditions. It’s like they are creating a new republic. Here in Curaçao, the whole city is then dominated by all these big wooden constructions. They make music, they sell food, they’re enjoying [themselves] with their families. This video installation is a big projection of these constructions in Curaçao. There is also an animation going through the video. The animation is based on a character I developed in 2009 called Captain Caribbean. He is a superhero who wants to save the Caribbean, but he doesn’t have superpowers. His power is that, because he has traveled a little bit more, he has much more knowledge, experience, insight, and things. And by using this knowledge and experience, he would like to help the Caribbean. At Carnival in the Caribbean, they have these plastic garden chairs. With these plastic garden chairs, I made the installation, combined with all kinds of objects that they have in Carnival.

SR: I am familiar with your Captain Caribbean! This piece was commissioned for São Paulo, so it’s different from other installations that you’ve done incorporating video, right? How did that translate? Was it a good experience being there?

TM: It was wonderful. I felt so good and so at home in São Paulo. It’s like you are in Curaçao, but much, much, much bigger. São Paulo is huge. You know, you keep on driving, and the city doesn’t end. I’ve been to New York, and when you are in a tall building, you see the horizon. But in São Paulo, you don’t see the horizon. It’s still buildings and buildings and buildings and buildings. Also, in São Paulo, the culture is very familiar. For me, it’s like being at home. The people are super-friendly. The food is wonderful. I was very surprised how cheap it is there. I got the feeling that art there is also something different than in the West. There is an urgency. It’s really about daily life. It’s about expression and communication. It’s about creativity, in a way, so that you can survive— not only in a materialistic way, but also in a spiritual way—so that, in your mind, you can be creative in how you define your everyday life. In order to keep on living.

In the last 10 years, the government has made a kind of adaptation of the culture here [in Curaçao] to make it more attractive for tourists. You do not see this urgency that used to be very visible on the island. The creativity—you don’t see that anymore. Now, it’s much more about the colors. The figurative. Yeah, the realistic thing, you know? It’s not about the artistic expression that finds its origin and urgency where artists communicate something that they want to communicate.

Tirzo Martha, Republic of the Caribbean, installation view, 2023, [courtesy of the artist and the Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil]

SR: I read about Captain Caribbean. I’m curious how you feel about how that persona has been reframed by art historians and curators in the Caribbean and the Netherlands. I appreciate you describing him as a superhero—a champion—for the Caribbean. For Curaçao, specifically. But there’s something [in how the work has been framed] that problematizes or challenges your envisioning of that persona. And how you view Curaçao, let’s say. I know that Curaçao is your home. You have deep, deep connections to it. You have a lucid idea of what Curaçao is for you, and it’s rather complex.

TM: Yeah, but the thing is that the Caribbean is very complicated. It’s complicated because of its colonial history. You know, the English were different than the French were different than the Spanish were different than the Dutch. So, these differences, up till today, are very deep in our bones, in our existence. One thing that we must not forget is that, up till now, we enjoy a system of education that is very Western. It’s a Western structure of education. And, most of the time, the structure that you get is the one that defines your content, your knowledge, and so on. So, each one of these islands has their own way of dealing with themselves. They have their own way of dealing with their history. They also have their own way of dealing with where they would like to go, in terms of their island’s future. And that’s the big thing of Captain Caribbean—Captain Caribbean wants to make them aware of the fact that, hey, we are all part of the same complication, we are all part of the same problems. We are all part of the same daily struggles to free ourselves from all this history. Maybe we are not going to be able to free ourselves of it, but at least we can be aware of it and be aware that we must not only support each other … we must also protect each other. The complications are the same, the consequences of all this—this history—is the same.

So, for Captain Caribbean, it’s about the struggle of bringing us together. Because of this fragmentation of the islands, we are very fragile. We are easy to be attacked. If something happens in Jamaica, what are we going to do? And the other thing is, each one of us has our own perceptions of how we deal with interpretation. I like the fact that people are searching for something in this Captain Caribbean thing. It’s a very important component in my practice as an artist.

Tirzo Martha, Scare Nigguh, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

SR: Talk to me about your relationship to myth.

TM: My relationship to myth. [Tirzo laughs and points to a new artwork behind him titled True Rumors] That’s my thing with myth. Most of the time, myth is a myth and didn’t happen, or part of it is true, but it still inspires—by creating a myth. Especially on these islands. Rumors and myth are very important, and a lot of [the] time, they obviously have a big impact on how people think, how they function, and how they deal with themselves.

SR: I can see that myth is a thread running throughout the different works. And I like how you complicate myth, and how you might be looking at how Curaçao flies under the radar of most of the West. When we talk about the Caribbean, we may think of Jamaica, Haiti, Martinique. I feel like Curaçao is under the radar in ways that might protect it from intrusion.

Tirzo, you are aware of how myth can ground and empower a culture, signal important aspects of Curaçaoan history, while also getting caught in the fray of how Curaçao has been misrepresented or romanticized in some ways, even by its own citizens. So, I think it’s interesting how you use myth in everyday objects. I’m looking at The Great Epiphany of Curaçao, which is an older work from 2014. I looked at that and [thought], oh, Tirzo is painting, and I thought about Mark Bradford when I saw it. The lights that illuminate the welcome mat, or these little toys that are sticking out of the object on this expanse, or the umbrella, which almost becomes a magical totem.

TM: Yeah, the way we try to make it a romantic story is remarkable, because that’s how we make it acceptable. The hero wins at the end. And that’s something very present in the culture here on the island. We don’t need to worry, because the sun will shine tomorrow. Then you can start all over again.

But, in some cases, things aren’t that easy. So, that’s why, in a work that I made for the Brooklyn Museum, there are these two plates. One is: Your destiny is in your hand. The other is: There’s the strength of God. When you do well, you always say, I have destiny in my own hand. But when things don’t work out, then you say, it’s God’s will. So, between these two extremes is the island’s cultural mentality. Sometimes that creates very beautiful things and conditions that are very important in how people live their lives here—how they deal with their conditions, how they look at the future.

SR: The objects themselves feel very much like a staging, or maybe restaging, of something—whether it’s history or something internalized.

Tirzo Martha, Republic of the Caribbean, installation view, 2023, [courtesy of the artist and the Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil]

Tirzo Martha, Republic of the Caribbean, installation view, 2023, [courtesy of the artist and the Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil]

Tirzo Martha, Republic of the Caribbean, installation view, 2023, [courtesy of the artist and the Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil]

TM: Yes, they are the restaging of the daily conditions and situations of people’s life. The way that I restage them is that I create a composition of the different objects of daily life. But in these compositions, I apply certain objects that don’t fit. By doing this, I create a kind of dynamic that brings people into another way of looking, or dealing with their daily life. For example, people who live in very small houses today, they don’t have a kitchen. They have a table and this small room, and on this table, they eat, they iron their clothes, they wash the dishes, they do everything. So, this table is organized in a way that they can do everything they need to do on this table. Their structure of how the objects are organized, I take that along in the work, and I put something on this table that doesn’t fit there, to show how extreme people can be with their use. For example, the ironing of your pants on the table where you do your dishes—that they have to improvise with what they have to make their life function.

SR: I like that you say improvisation. Reality improvised. People reimagine themselves. This table, I see it very clearly, this table that it’s an ironing board and a sink and a place to eat. It’s more than resourcefulness. It’s the will to create something. To reconceptualize your own life.

TM: Yeah, the improvisation is because they want to make their life pleasant. It must be clean, it must be functional. It must add something to my personification of who I am. Everything is clean. The carpet will be a light color so people see that it’s clean.

SR: I’ve seen people write about your work as “misleading” or “intentionally confusing.” No one has used the term trickster yet in anything that I’ve seen written about you, which is interesting. I don’t think you would frame your work, or even your role as Captain Caribbean, as such. In your work Rhethorical Obstruction (2016), the binding, the illumination, the text, the right angle—there’s so much information in this small space. And then there’s the quandary of the wordplay with “rhethorical.” I love the language of it, which takes me to writers and thinkers from the Caribbean such as Césaire and Glissant. Can you talk a little bit more about disrupting the text, the language?

TM: It has to do with improvisation. Not only in Curaçao. I see it also with other people from the Caribbean. I’m not sure how you call it in English, but here, we have this thing where you are, like, trying to create a convincing story, you know, that I am late, and then you start with a long story. It basically doesn’t matter. You can just say, I am late because my car broke down. [But] you don’t say that. No, you say, I’m late because, this morning, I stood up and I wasn’t feeling well. And then I stepped on the dog, and the dog bit me. And then I went to wash my leg, and then I came back, and at the end, I went to start my car, and it was broken. You’re creating this whole story as an argument of your being late.

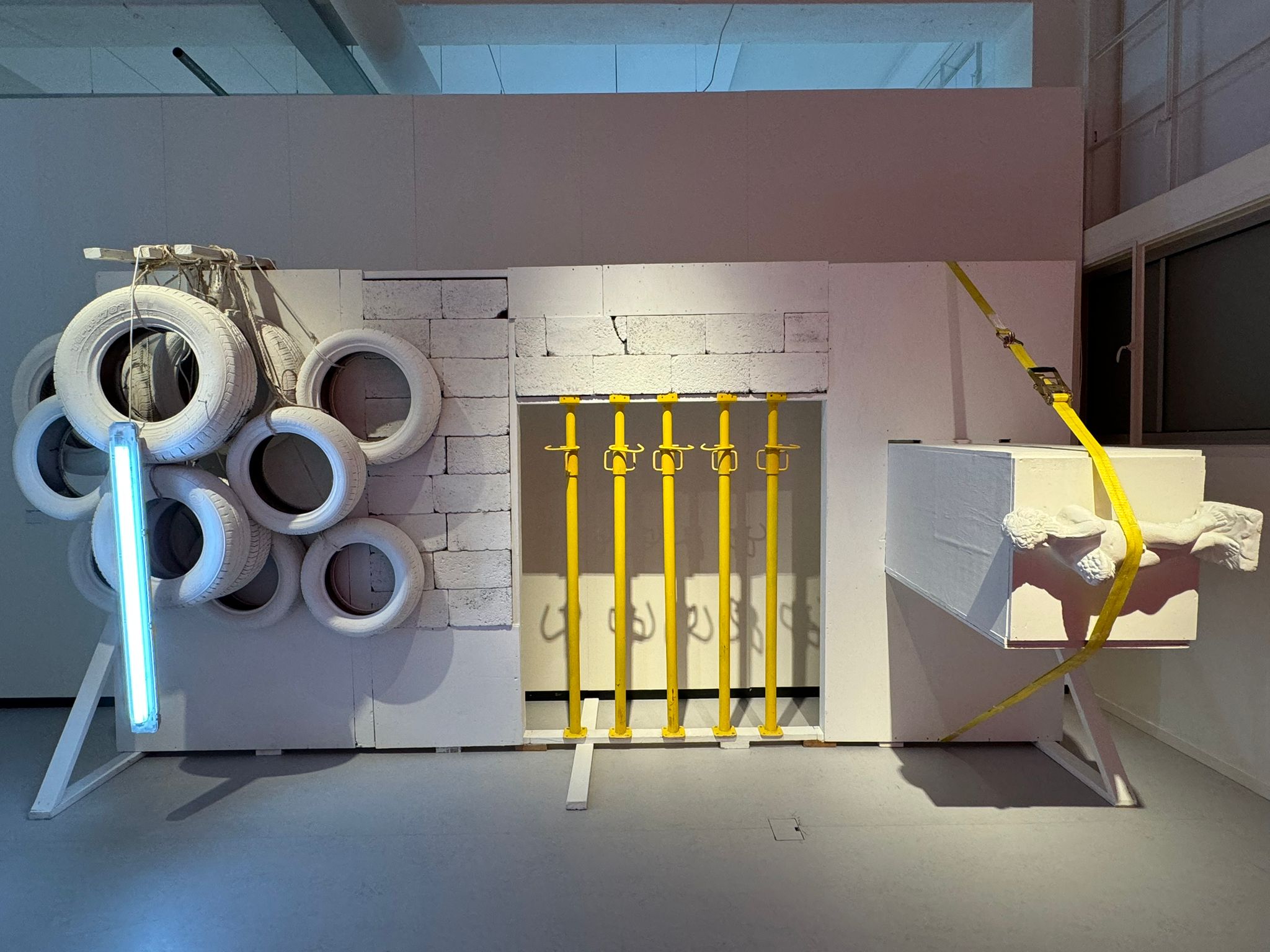

Tirzo Martha, Rhethorical Obstruction, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

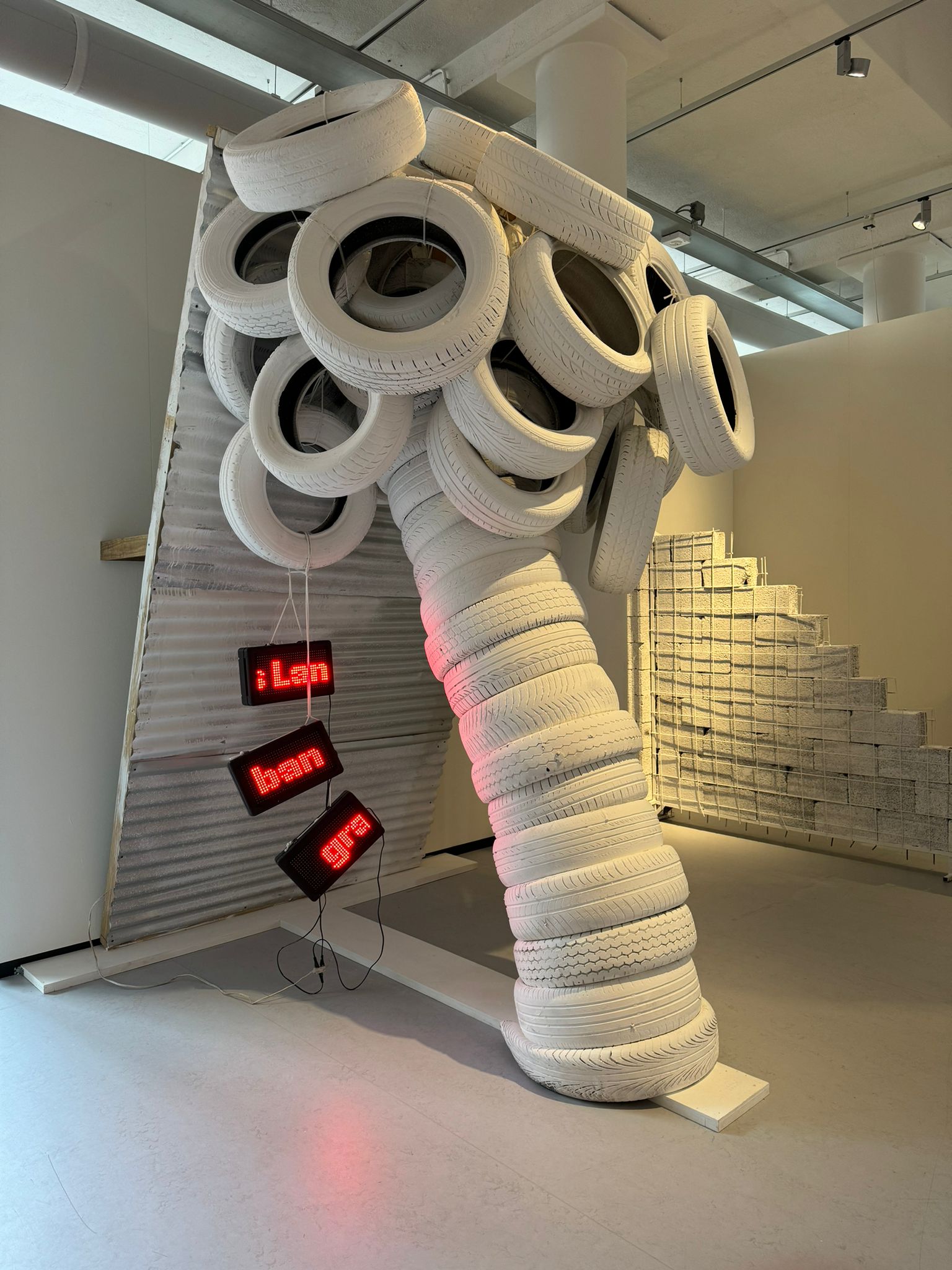

Tirzo Martha, Untitled, 2022 [courtesy of the artist]

So, it’s the same thing with the [works’] titles. The titles are a kind of argument, and the argument is just part of one thing, and you didn’t necessarily need to talk about it. But you take it always along with you, this long story, you know? There is this interaction, and going forward and back with this communication between the object and the title. Still, the idea of [a work being] untitled [is] an argument for the work—what you present as the argument—but in the end, the argument becomes something else. You try to give credibility to the story. That’s the idea.

SR: Credibility. The relationship between title and object, but also [between] the title and the object and the viewer. Because most viewers feel like the title is going to be the secret key to unlock everything.

TM: Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. And that’s the disappointment. That it’s not the secret key.

SR: So, the title leads you somewhere else. Is that somewhere else accurate? Is the accurate thing that you’re closer to something that’s right in front of you?

TM: It’s about denial. You are denying. What you are denying, that’s the truth. That’s the reality. And you’re denying it by creating a story to make it acceptable for other people. And what are they now going to do with the story?

SR: Symbolism has a very specific presence, from work to work, and operates differently in each one. I’m struck by how the pieces are never literal. Never didactic. Even though you’re speaking to the viewer in a way that is getting to the core of the thing. There’s a kind of direct address, for sure, but the symbolism and the myth and the restaging and the improvisation are done in such a way that it’s not didactic. It’s not a one to one. There’s something else at play here.

TM: That is because I don’t use the objects and the compositions in a symbolic way. I don’t believe in symbolism. But I know that other people do believe in symbolism. The composition needs to bring a kind of confrontation to the viewer. You see, symbolism isn’t a strict thing.

SR: The accumulation, though, gets into what you characterize as a Curaçaoan tendency or predicament. The accumulation of things, of objects, becomes not necessarily how they define themselves, but it’s key to the narrative. It doesn’t tie into the attachment to commodity in the same way as it does in the West. It’s something else.

TM: If you grow up with a lot of poverty, you are being taught that success is to have all these material possessions. Success has a certain image.

SR: The urge to do that is also tied into just wanting to be seen as human. You know, wanting to be seen as valuable. And our humanity is forever linked with this materialism.

TM: I believe that civilization didn’t begin with us making things. Civilization began the moment that we started taking care of each other. We need to protect each other. Art is something that is very important to our existence, because it is the validation of our existence with our urgency to express ourselves.

SR: I want to end with an image in one of your pieces, Pilgrimage to the Holy Caribbean. There is a small statue of Jesus, robed. And tied—or rather, taped—to his body, to his chest, is a small transistor radio.

TM: Yes, the transistor radio has a [recording of a] politician talking the whole time, saying that we have the support of God. You know, it’s very traditional in America that the presidents, at the end, say, “God bless America.” As if America is the one who gets all the blessing. [laughter] Politicians use religion all of the time. Religion and politics are so contradictive. How politicians use Jesus and God as their example, it’s crazy. So, that’s why I say there’s a pilgrimage to the Caribbean. It’s about the manipulation. They are fighting for their own interest, and they don’t care about the rest. They just do their thing. And then, when they finish, they go and retire, and they’re super-rich, and nothing new has happened.

Tirzo Martha, Untitled, 2022 [courtesy of the artist]

Tirzo Martha, Republic of the Caribbean, installation view, 2023, [courtesy of the artist and the Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil]

This text is part of ART PAPERS Spring 2024 theme, Interpreting Site, is guest edited by Sherae Rimpsey, the inaugural Mildred Thompson Arts Writing + Editorial Fellow.

Sherae Rimpsey is an artist and writer. Her book of poetry—neon neon—is available now from SHINKOYO / ARTIST POOL. Rimpsey is the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation–funded Mildred Thompson Art Writing and Editorial Fellow for ART PAPERS in partnership with the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University.