The Un-Heroic Act

The Un-Heroic Act, installation view, 2018 [photo: Bill Pangburn; courtesy of Shiva Gallery, John Jay College, New York]

Share:

Content Warning: This review contains descriptions and visual depictions of sexual assault.

In late September 2018, Christine Blasey Ford testified against Brett Kavanaugh, and Bill Cosby appeared at a sentencing hearing, having been convicted of aggravated indecent assault after decades of rape allegations against him. “Crime is down” headlines proliferated in the news while reported rapes in New York City increased by 28%, and The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the U.S. [September 4–November 3, 2018] opened its doors to the public. 1

The exhibition’s 20 carefully selected works represent artists including Yoko Ono, Ana Mendieta, Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, Kathleen Gilje, and Natalie Frank, exposing the long-term effects of life after rape. The Un-Heroic Act presents three generations of artists—with the oldest work by Yoko Ono, from 1968, and the newest work from a workshop done on September 28, 2018 in collaboration with Guerrilla Girls BroadBand. In curator Monika Fabijanska’s words, “As we were watching what was going on in Washington, they were working on this poster. …. It will be present in the gallery, but it will also be posted across [the John Jay College] campus.”2 The Un-Heroic Act gives survivors a public voice and speaks not of the act but to its aftereffects.

The exhibition takes its title from Susan Brownmiller’s theory of “heroic” rape. She noted the glorified and sterilized depiction of rape in the work of male artists who turned the act into one of romantic desire and conquest. Historically, heroic depictions of rape expose sensuously helpless bodies. They are demure, yielding, and fleshy. They are “nude,” never naked. These images are historically created by men: Poussin, Correggio, Titian, Botticelli, Magritte, Picasso. A packed rolodex of dead male artists whose work romanticizes and idealizes rape sits on the desk of every art historian.

The Un-Heroic Act presents an alternative canon, investigating the seismic aftereffects of rape as a physical, emotional, and cultural trauma. Rape is never heroic, and the show is clear about this fact from the outset. By refusing to mitigate or censor the painful elements of rape, Fabijanska discovered multiple iconographies of unheroic rape images within contemporary women’s art.

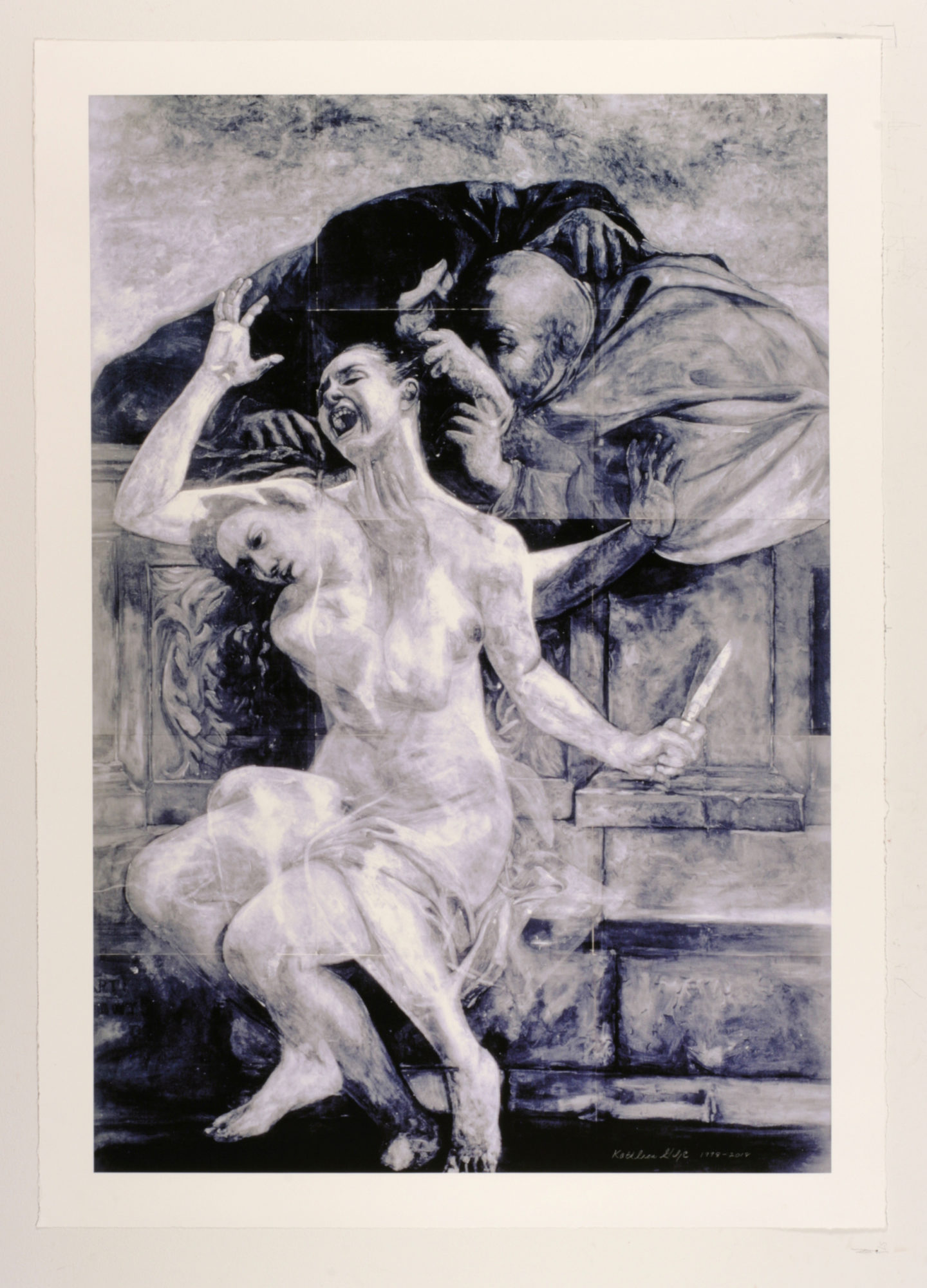

The canonical revision begins with Susanna. A grisaille x-ray repainting of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders by Kathleen Gilje shatters the usually calm entry space of Shiva Gallery. Positioned to the right of Gilje’s work, the exhibition title spans more than 10 feet of wall space, declaring the The Un-Heroic Act in all caps, naming the unnamed, and instantly shouldering the viewer with the historical fantasy of rape.

Kathleen Gilje, Susanna and the Elders, Restored, 1998/2018, X-ray image on Arches paper, 52.5 x 36.75 inches [photo: Monika Fabijanska; ©2018 Kathleen Gilje; courtesy of the artist and Shiva Gallery, John Jay College, New York]

Susanna is the victim of sexual harassment, abuse, a flawed legal system, and a history of romantically sexualized imagery. In 1610 Artemisia Gentileschi unbound Susanna from the objectification of the male gaze in her compressed, resistant composition. Almost 400 years later, Kathleen Gilje revealed that the story of Susanna was a mirror for Gentileschi’s own life. The artist was raped at age 19 by her teacher, around the age Susanna was raped. 3 Gilje’s painting prepares the audience to view the 19 other works in the exhibition through a historical lens, emphasizing the presence of these works throughout history as potent but consistently censored.

The exhibition appears to be organized around three subjects: the social, the personal, and the political. Susanna and the Elders, Restored (1998/2018) embodies the first iconography that Fabijanska identifies: the real experience of historical myth. Gilje’s work is social, in that it deals with history and culture, but each of the works in the show touches upon elements of all three categories.

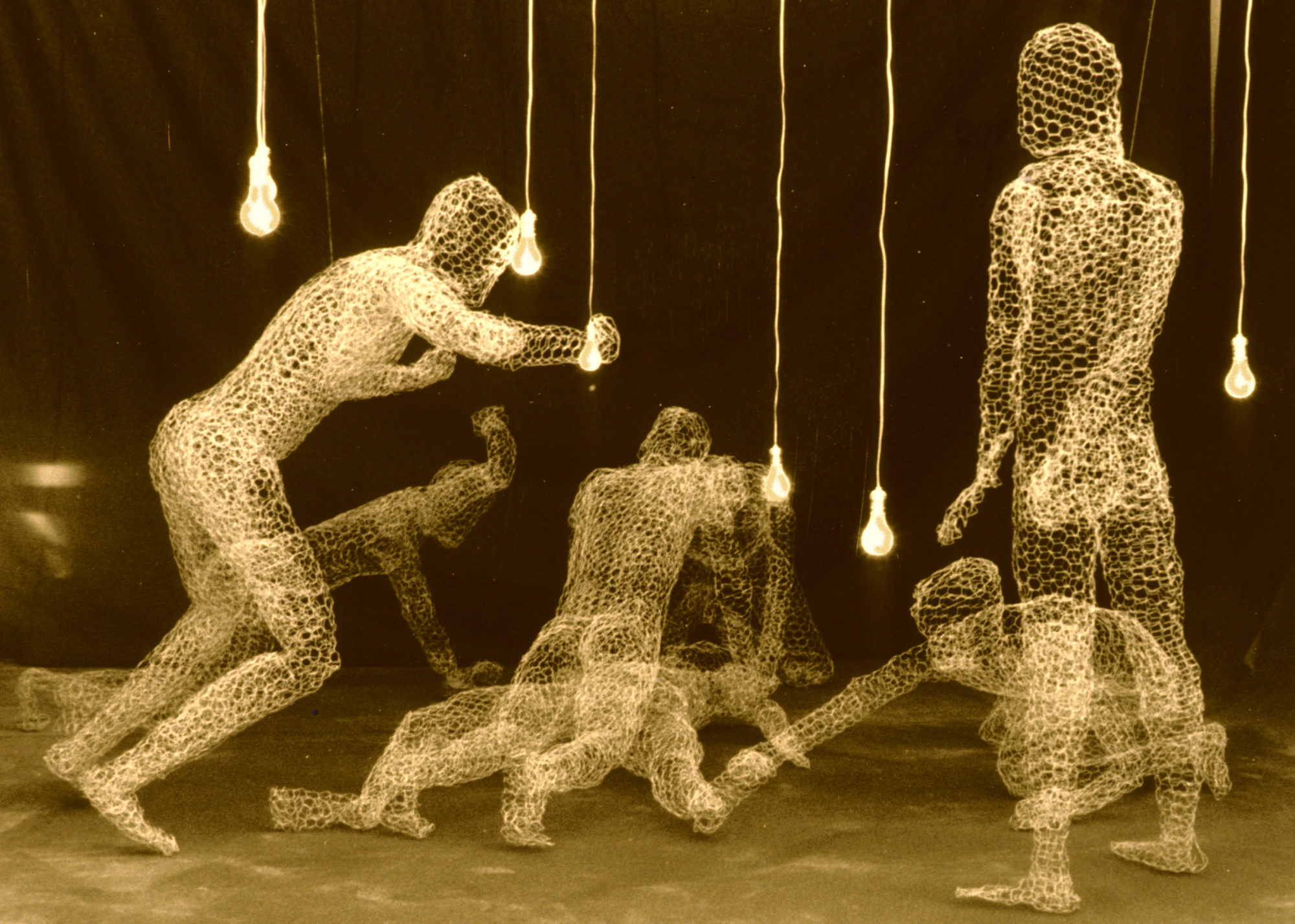

Just past the entrance, Carolee Thea’s Sabine Woman (1991) manifests as chicken wire ghosts of gang rape floating before the viewer. This work is an impression—a blurry personal memory imprinted in the audience’s mind, akin to the experience of partial memories left by trauma. In the very back of the gallery, a darkened screening room shows work by the youngest artist in the exhibition: Naima Ramos-Chapman. And Nothing Happened (2016) is a gut-wrenching video that the personal category by depicting everyday life after rape. Minute changes in behavior, small discomforts, and triggers slowly give the audience a glimpse of the dispassionate pain suffered daily by survivors.

Carolee Thea, Sabine Woman, 1991, chicken wire, electrical wire, sockets, bulbs, sound, dimensions variable [©1991/2018 Carolee Thea; courtesy of the artist and Shiva Gallery, New York]

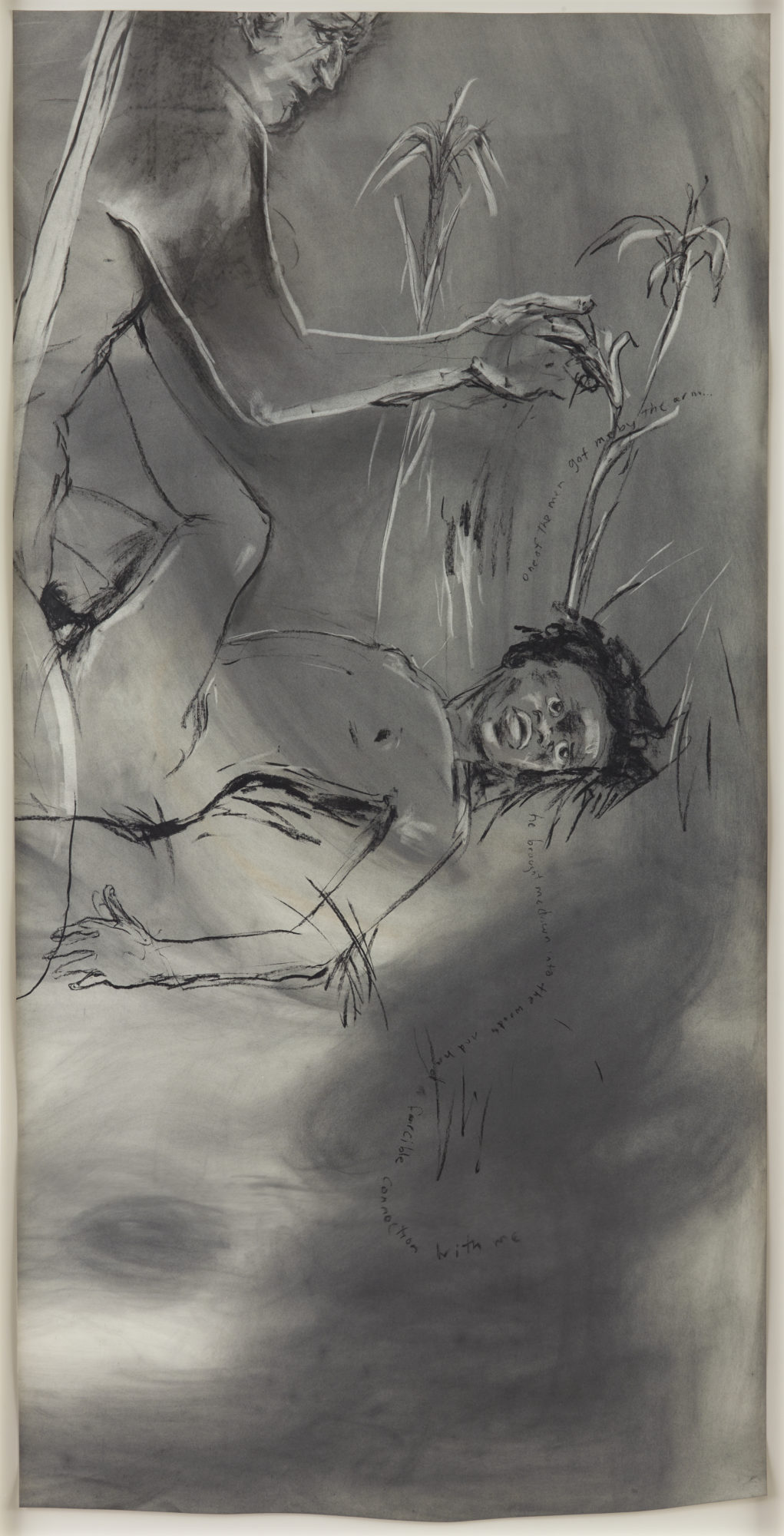

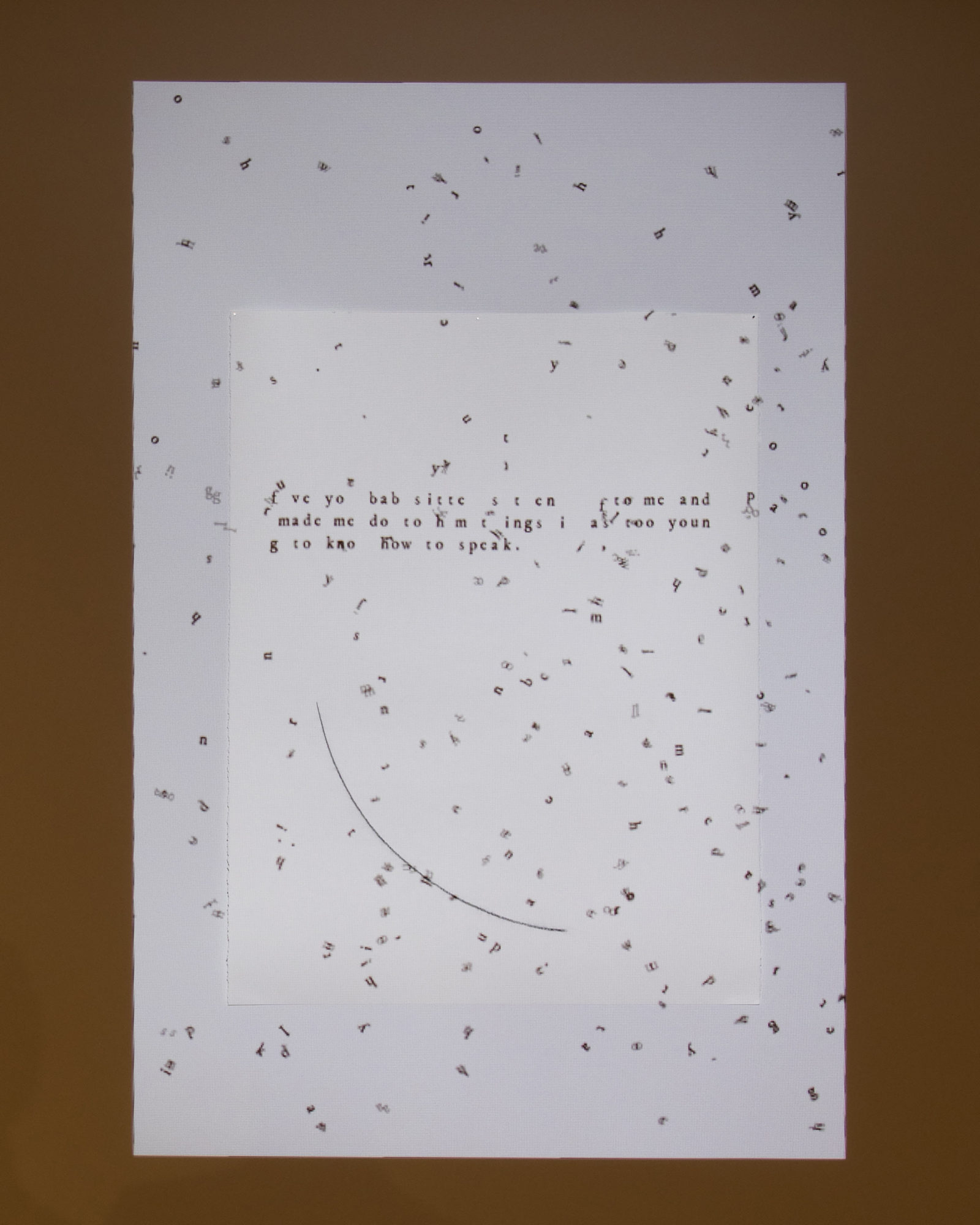

Through the deposition of Amanda Willis, a 12-year-old girl who was raped in 1866, Kara Walker’s work examines rape as a racist tool of segregation in the United States. Walker weaves portions of the child’s words into the image, and the full statement is available in the accompanying wall text. Another daring political work is by Bang Geul Han. Through the Gaps Between My Teeth (2017) compiles the 4,600 public testimonials made by women in reaction to the Access Hollywood tape recording of Donald Trump suggesting that he had committed sexual assault. These five works demonstrate the three categories addressed in The Un-Heroic Act, and together, all 20 exemplify the systemic nature of rape in America.

Fabijanska ’s research notes that “rape constitutes one of [the] central themes in women’s art,” but she acknowledges the limited scope of the exhibition.4 The Un-Heroic Act comprises art made by self-identified women artists who live and make work in the United States. This focus restrains the types of iconographies present, but Fabijanska “decided we must speak about what is going on here, and now, and around us.”5

What makes The Un-Heroic Act groundbreaking is Fabijanska’s iconographic formula, her focus on the lasting psychological devastation experienced by survivors, and her selection of works by such well-known artists as Ana Mendieta that have not been shown, that have been censored, or that have suffered from bland curatorial frameworks that avoided directly referencing rape.

Ana Mendieta, Rape Scene, 1973 (Estate print, 2001), suite of five color photographs, 16 x 20 inches each [photo: Monika Fabijanska; © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC; courtesy of the artist and Shiva Gallery, John Jay College, New York]

Many narratives about rape attempt to diminish women, either through hypersexualizing and romanticizing images of the act, or through disregarding or ignoring testimonials. A public exhibition that presents the brutality and trauma of rape can combat those narratives with a new type of social evidence, which encourages others to model their behavior in a given situation after the artists of The Un-Heroic Act. This counter-narrative provides a new social model for women: it encourages speech and visibility, and—above all—it aids in erasing the stigma of shame and isolation. A public exhibition that attempts to create a revised iconography of rape lifts the veil of shame from the shoulders of victims to cover the heroic monuments of male rape romantics.

The Un-Heroic Act is an exhibition with motivation, and its motivation is infectious. This counter-canon of woman artists has generated an atmosphere of solidarity. The Un-Heroic Act is staggering in its ambition and its seemingly clairvoyant timing. Although it ultimately would have benefitted from four more floors of exhibition space and a team of research assistants, I believe that this exhibition is unparalleled.

Rape is not about sex. Rape is about power. The Un-Heroic Act returns that power to survivors, providing allyship, visibility, and a platform that supports previously disenfranchised voices.

References

| ↑1 | The number of rapes reported in September 2017 was 118, with 1,053 in all of 2017. In September 2018 there were 144 reported rapes, with 1,348 rapes in all of 2018. See the NYPD statistics: http://nypdnews.com/2018/10/citywide-overall-crime-continues-decline-september-2018/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4 | Excerpted from Monika Fabijanska’s introduction to the symposium panel discussion on October 3, 2018, in the Moot Court at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. A recording of this talk has been made available through Shiva Gallery at: https://vimeo.com/292171966 |

| ↑3 | Gentileschi’s exact age at the time of the assault is still disputed. For more information on the opposing sides of this argument see: Elizabeth S. Cohen, “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 31, no. 1 (2000): 47–49. Ward Bissell, “Artemisia Gentileschi—A New Documented Chronology,” The Art Bulletin50, no. 2 (1968): 153. Here, Bissell notes that Gentileschi’s father claimed she was 15 at the time of the rape. Cohen places Gentileschi at age 16 at the time of her trial. All scholars agree that she was in young adulthood at the time of the assault. Bissel suggests that she was actually 19 “at the time of litigation” (see p. 154), and Gilje has also written as much on her website and stated it during the recent symposium at Shiva Gallery. Also see Gilje’s writing on the work, available through her website: https://kathleengilje.com/artwork/321721_Susanna_and_the_Elders_Restored_X_Ray.html |

| ↑5 | Ibid |