The Infinite Nature of Black

Paul Stephen Benjamin

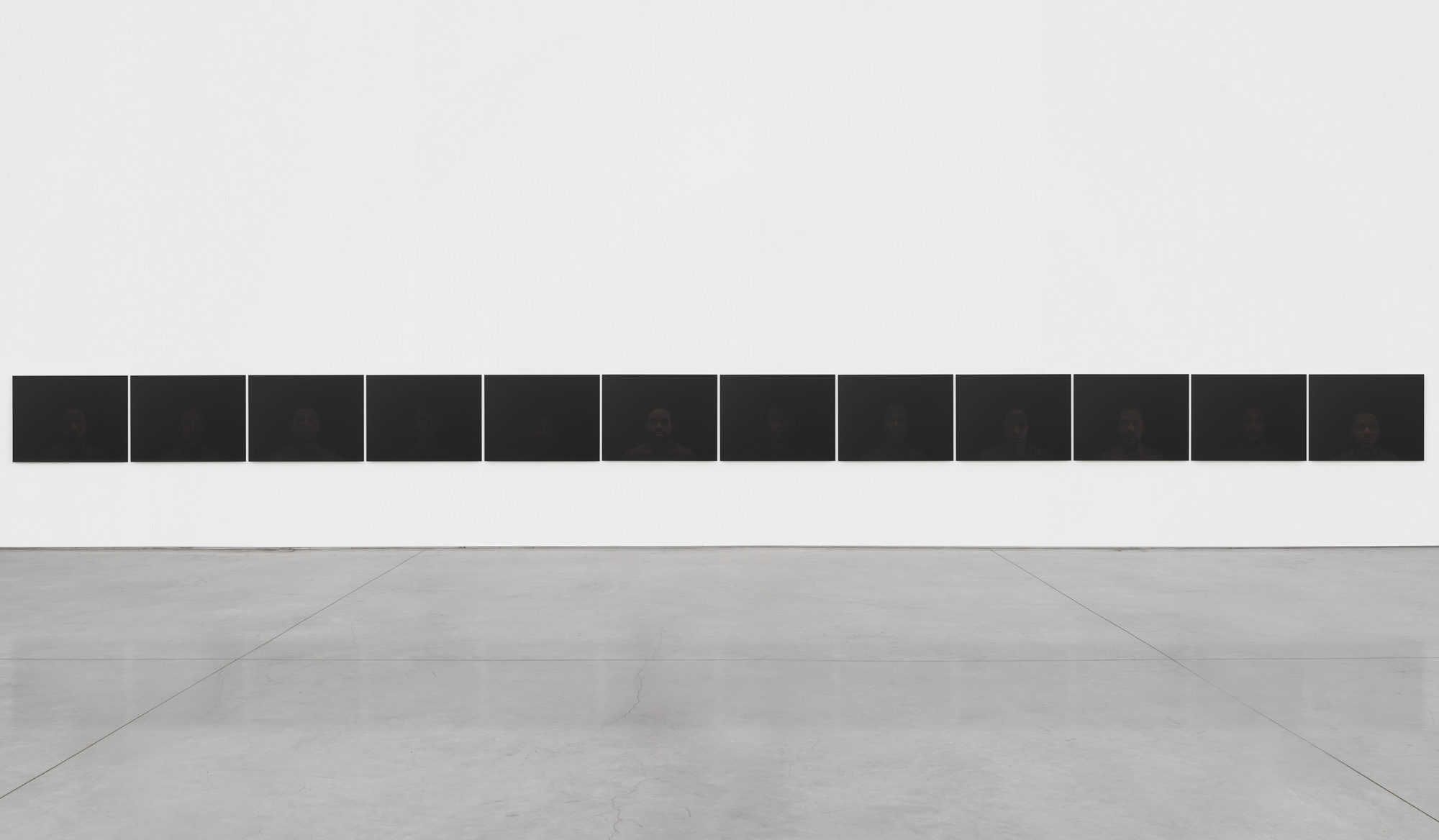

Black is the Color (Nina Simone), 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen.

Share:

Artist Paul Stephen Benjamin’s work explores the relevance, resonance, and poetics of the color black and ranges across media including photography, painting, video, and sculpture. His solo exhibition, Pure, Very, New, curated by Lisa Freiman for Marianne Boesky Gallery, brings together existing and new site-specific works that plumb the formal and linguistic associations with black and blackness.

Not long after the exhibition’s opening, we sat down together in his Atlanta home, beside an impressive array of snack foods, to have a long overdue chat. We discussed his belief in simplicity, the relationship between interpretation and artist intention, and the experience of preparing for his solo debut in New York City.

Sarah Higgins: I want to ask you a little about your work in general. At first glance, so to speak, there’s a real simplicity to the conceptual underpinning of your work: a very straightforward statement of an exploration of the color black. You’re kind of known for being really hesitant to provide much more front-loading in terms of the subject matter, or [of] breaking down your intent. You’re really often much more about instigating a response. Can you talk a little bit about how that position has emerged in your work and how that’s evolved over time?

Paul Stephen Benjamin: I would say, early on in my practice, I was interested in symbolism, metaphors, and narratives. My work was heavily influenced by that type of information. I was adding to the rich conversation of earlier artists with things that were relevant to me. Over time I began to realize that I didn’t have to fill my work with so much. I didn’t want my work to be didactic. I think, as an artist there are so many thoughts that go through your head. Not all of them need to be communicated. But it is a part of who you are, it is a part of the experience or the process. Eventually I got to the point where I didn’t want to dictate what people see, hear, or think. It is about the experience.

Flow, installation view, 2017 [photo: Object Studios; Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

SH: There’s a kind of shock of the nakedness of the un-textually mediated work of art. And I think about that as a curator and a writer a lot because you want to give people enough. You want to give people a window. But I think that impulse leads people to a place where they just want to be told. Like, “Just tell me what this means so that I can decide if I like what it means or not.”

PSB: I like that, in part my attempt to create a window or an entry point is through simplicity. Using things such as the title, how materials are listed and including all the information that is provided. The way that things are listed is important. Whether I’m talking about black power chords, or black extension cords, black lights, or Valspar New Black 4011-1 latex paint—those are a part of the conceptual makeup of the work. My interest is in creating this balance between aesthetic and concept. It gives people different entry points. So, conceptually, if you can’t get into [the work] then maybe you can [do so] aesthetically. Or hopefully through the process, the work, the labor that went behind it, something may speak to you. The beauty of the color black—if that’s all you get out of it, I’m okay with that. But then also conceptually, what does it mean when you say “new black,” “very black,” “black magic,” what connotations do those have? But even Nina Simone singing “Black Is the Color,” and her voice becomes abstract and the sound becomes meditative or the words become like a mantra.

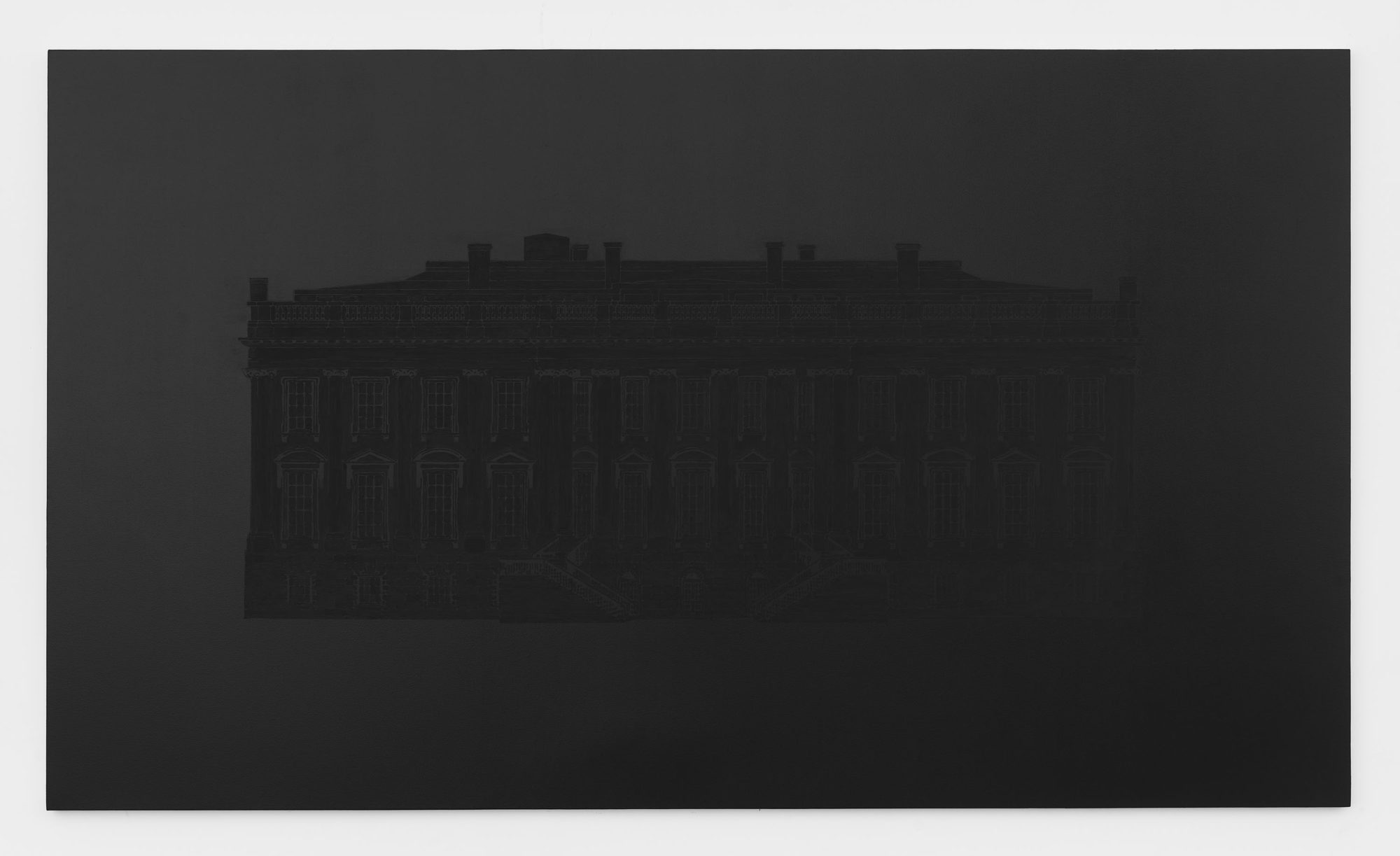

SH: I get the impression that the minimalism of the aesthetic of the work and the minimalism of the language are coming from a really poetic place, and a place where the bulk of the content and resonance is kind of left between the lines, but also alluded to really directly. And I know it’s even said in the press release and the essay for the exhibition, the open-ended and interpretive quality of your work is an important “completing facet.” And there’s a slipperiness there that is obviously political. It’s overtly political. There’s an all-black American flag, there’s the White House rendered in black.

PSB: I like how you initially stated that. But as an artist, I refrain from labeling myself a Minimalist. As you stated the poetic nature in which I’m working is very important. The information that I’m providing, for instance the black flag, is a black cotton flag made in Georgia. I never assigned that it’s an American flag, that there’s some political context behind it. I’m not saying that there isn’t. But at the same time, it’s material to me.

SH: True, but I’m going to push back on you, because it is sewn—while subtly and with a lot of nuance between the different black fabrics, their texture, the slight variation in the fabrics, the depth of the blackness—very clearly in the form of an American flag.

PSB: My studio is in the old cotton mill district, founded by Colonel Scott of the Confederate army, who was also one of the founders of Agnes Scott College, and started a cotton mill company in Scottdale, GA after he retired. So, there are a lot of things to it.

Paul Stephen Benjamin, Flow, 2017, installation detail, 36 x 48 inches [Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

SH: I completely respect a really hardline refusal to be prescriptive. And I think that there’s an importance [to] being a provocateur, in a way.

PSB: I don’t see myself as a provocateur.

SH: Well, there is clearly a depth of content that goes beyond the very beginning stages of interpretation. But I think that there is a difference between refusing to be prescriptive and disavowing the content that you have provided very clear entry points into.

PSB: So, I won’t disavow it.

SH: Okay.

PSB: I will say it is very much a part of the work, but that’s not all the work is limited to. What I’ve experienced as an artist [is that] once you assign that kind of content, whether you intend for it to be prescriptive or not, that’s what will be received and that’s what will be heard, articulated, and communicated on and on. “This is what the artist said.” Soon as you assign one aspect to it, that’s what it becomes, and for me it limits its ability to move forward and it limits its power to have even broader meaning.

SH: I guess part of why I feel inclined to press you on there being social and political content certainly has to do with our times. I believe to be apolitical is to be political. And I see in your work a very open-ended prompt to consider our times. Not to say that I’m searching for what your message is or what your personal position is within that—as much as to say that your work, to me, asks for a conversation that is a political conversation. And then in some ways, the work becomes the room in which you have the conversation, rather than a moderator of that conversation.

PSB: I won’t disagree with that. I think it’s very much a part of the work, but where I guess I have to pause to kind of redirect the conversation is, oftentimes with work there is this political climate, current events, and the work is not created based on that. If you look at some of that work based off of what’s [happening] today, this work was created before this situation, or it was conceived before it. Not that it does not entail or include the many facets that are the underbelly of it. I’m not denying that. I had a random question or comment from someone who saw some of my work—and was like, “Is this related to Black Lives Matter?” And I said, “I didn’t create this because of Black Lives Matter. Now if you see an association with it, I won’t deny that’s possibly a part of it. But I’m not responding to Black Lives Matter, or whoever the president is.” I don’t work in that way. Now, over time, I think that’s the beauty of the work—is that you can make these associations.

SH: So, you’re very open to interpretation, but very resistant to having any interpretation projected back onto you as intention. Would that be a fair way to phrase that?

PSB: If I said something, then yeah, you can write that. But to say that, “This is what the artist is saying,” I push back on that.

SH: Well, and, not to call you a poet—

PSB: I’m okay with that! I won’t call myself a poet.

Ceiling, installation view, 2017 [photo: Jason Wvche; Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

SH: There’s a vein in contemporary art of people who kind of get termed “materialist poets.” I would probably put you in that category (not that I would ever say you would want to be in that category). There’s a kind of violence that you can do to a poem by asking the poet to write an essay about the poem, but it doesn’t mean that the poet doesn’t want someone else to write an essay about the poem. But, you know, I’ve always found myself in those moments where I’ve witnessed you being asked very specific questions, being asked to decode your work.

PSB: And I won’t do that.

SH: Right. And watching you navigate your own refusal to do so, in a variety of different contexts, whether it was an artist talk or at an opening, I’m always impressed because I feel like you handle it very deftly and politely, but without conceding. But for me, it’s always taken me back to conversations around when black people in community with white people are asked to explain racial dynamics to the white person. When they are asked to do the labor of decoding, or teaching, or arguing for a history that is there, to be learned about. And at what point can white people stop asking their black friends and acquaintances to do this labor for them? And to me, it’s a similar thing. Often when I see you asked to decode your work it’s a white audience member or white collector who is saying like, “Confirm for me what I’m allowed to think about this.” It always reminds me of those moments when the argument gets made, like, don’t ask me to explain a history to you that you’ve had access to your whole life, so that you can have it in this neat, bite-sized thing.

PSB: I’ve certainly experienced that, but I mean, I have black people wanting the same thing. That’s a part of the work, that there are so many different perspectives and aspects, that there is this assumption that everyone thinks the same. And so, it doesn’t make a difference who the audience is that’s asking that question. With the importance of the artist making work, and all the efforts that go into it, it’s almost insulting when someone comes up and says, “Tell me about it.” What they’re telling me is that they have no interest, but [they’re asking me to] give them the quick and dirty.

I cannot limit the ability of my work to move forward by just ascribing a set of bullet points. I like looking at things long term. So once we get out of say, this particular era, what are the works that were created during this time? What do they mean 10 years from now, 15, 20 …?

The political climate now is not [the same as] when that work was conceived in 2013, 2014. If you find relevancy, that’s because the color black is relevant. And everything that goes with it is this continuation, it’s this compression of time and space—that the infinite nature of black or blackness, the longevity in history of the color black and being black, or the blackness associated with it is very important. I don’t know if I answered your question, but ….

Paul Stephen Benjamin, Paint The White House Totally Black, 2017, Behr Totally Black HDC-MD_04 on canvas, 84 x 144 inches [photo: Object Studios; Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

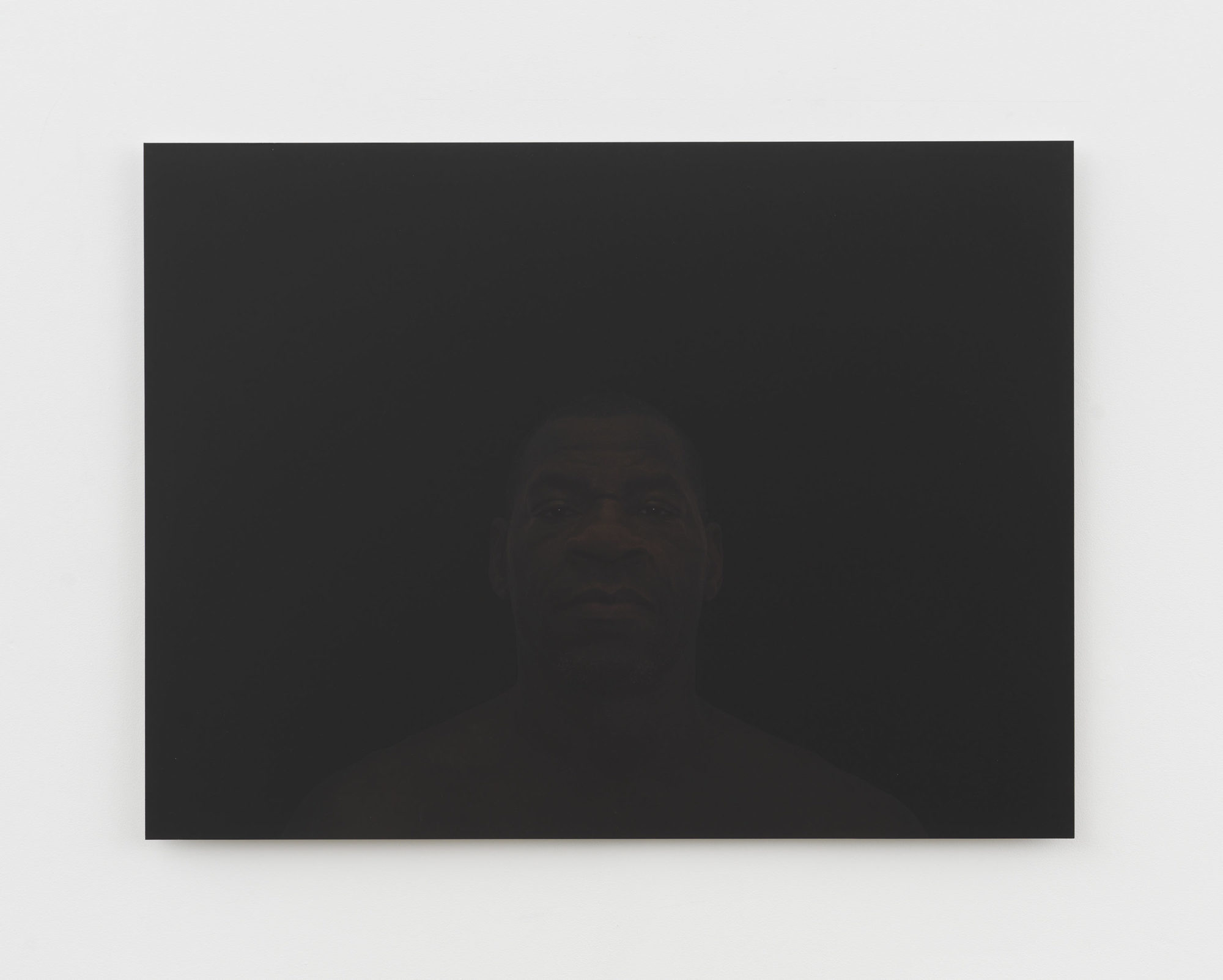

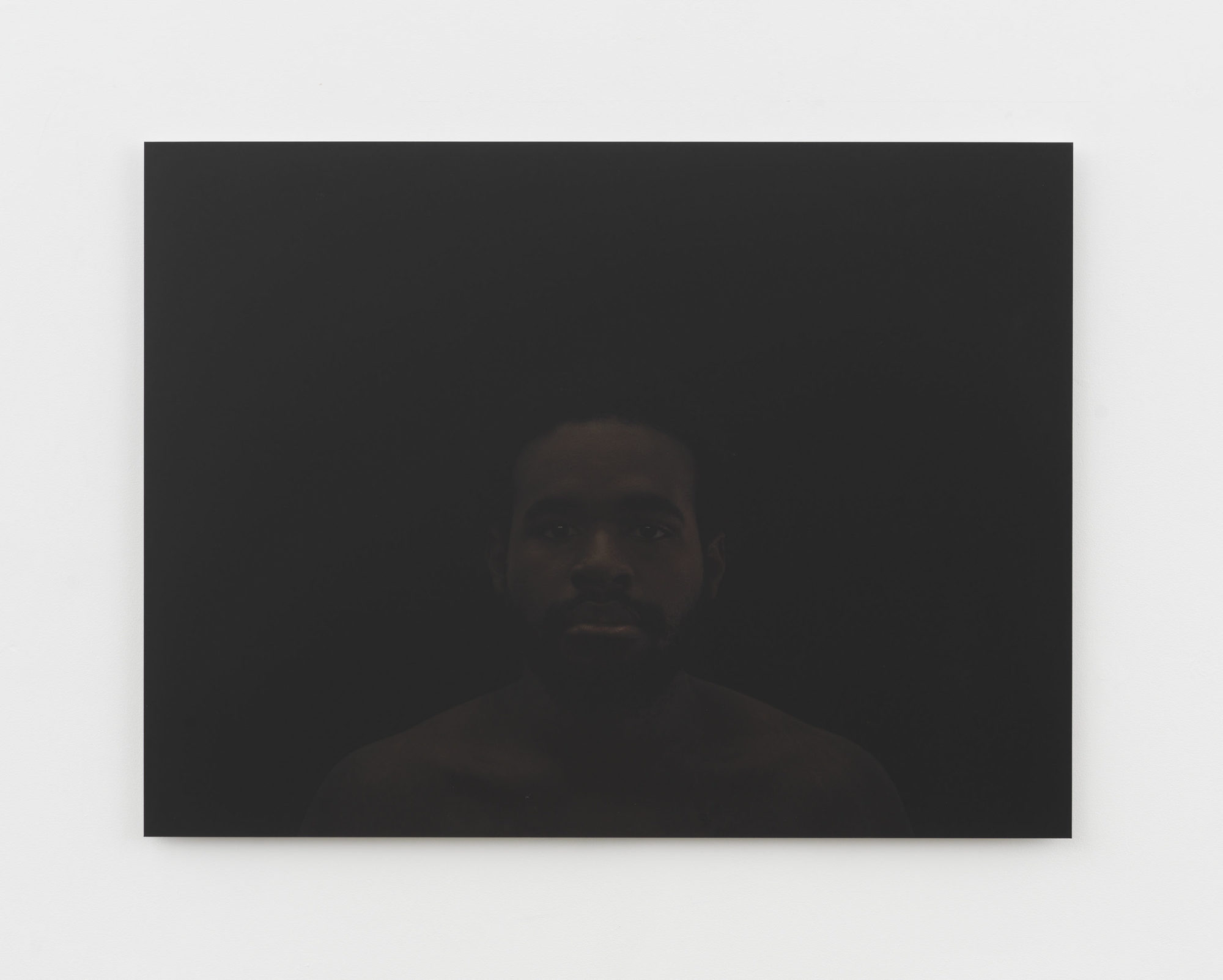

SH: Yeah, I think so. Or at least I like what you said and wouldn’t have you go back. I think that seeing the photographs in Marianne Boesky Gallery, the portraits that are these dark, horizontal portraits of black men and at least one boy, or young man.

PSB: My son Joshua. He was five at the time, he just turned eight.

SH: Yes, and also one of yourself! There’s a self-portrait in there. They are rendered in such a way that they’re sort of busts. The shoulders and faces of this row of men emerges—they almost have a holographic look. They feel like windows into a really uncanny three-dimensional space. In the installation at Marianne Boesky, those works are on display in the room with a large painting of the White House painted totally in blacks, and with the flag work, and I’d never seen those three works placed together before, and it allowed me to experience it in a different kind of spatial reality. It all just fits the space so well, it’s hard to believe that so much of it is work that was made for other spaces.

PSB: I work in series. The series can evolve just as the individual works evolve. The portraits started out as a video project. The space in the gallery was important, placing the flag on the pole to extend upward, and taking advantage of the height of the ceiling allowed me to expand the scale of the work. The lights casting the shadow of the flag. Adding new elements throughout the exhibition was important. We added black lights to some of the ceiling and floor fixtures. They became part of site specific works throughout the gallery.

Paul Stephen Benjamin, Ceiling, installation detail, dimensions variable [Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

SH: There are the two spaces at Boesky Gallery, connected at the back by kind of a pass-through. And there’s a new work, one of the blacklight works, that exists in that pass-through. And I was thinking about it being a kind of transitional space or a liminal space. To me, there’s something about the intensity of the blacklight in that room, and the way people reacted to being exposed to it that felt like a purification as you pass through these two sides of this exhibition-as-diptych. That’s the interpretation I brought to it, but would you tell me a little about making work for that space? Did you make that work for that space?

PSB: So, it’s a site-specific work. It was interesting because having the galleries in the two spaces, that’s the way in which to keep a consistent flow. Which, in some ways, I guess disrupts the space because there’s viewing rooms and there’s private space. But it was really this interest in how do I, as a sculptor or a person dealing with light and sound, how do I manipulate this space so that the experience and the encounter is immersive? So, painting each of the walls in Pure, Very, New is a continuation from what I had done at the Telfair, when we painted that whole gallery space. And so that in itself was an installation and then adding the blacklight so that when you entered that space from any direction, the power of the suggestion of what it meant to be in there. What does it mean to be within blacklight? What’s revealed? What’s experienced? Just hearing it, what does that mean? It brings different connotations. Some people talk about their 60s posters that they saw in blacklight, but then [for] other people it is totally more—I keep using this word—nuanced, that deals with their experiences.

SH: I found it to be a kind of a way for me of realizing how contaminated I was.

PSB: Because it reveals everything.

Paul Stephen Benjamin, Flow, 2017, installation detail, 36 x 48 inches [Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen]

SH: Yeah! It revealed every piece of lint. It basically revealed every white thing on me. The white dog hairs on my coat. And I remember your kids being really taken with the way it was making their eyes and teeth glow. And it places so much attention on your body and the bodies of the other people in the room, that I feel like everyone that passes through that space becomes implicated in the work in a way that was powerful, but particularly because it was in this sort of transition space from one side of the exhibition to the other.

PSB: What’s interesting about what you said as well is that no one is immune when they go in that space of having details revealed. So no matter how perfect or imperfect you are, that blacklight will reveal many different things.

SH: You and I have the nice coincidence of both living in Atlanta, so I can pick your brain another time. But before we end our conversation, is there anything that you’d like to say about the experience of this exhibition, or your work now?

PSB: The evolution of the work is important, the spaces in which the work is presented are equally important. I will continue to mine the color black and pursue all aspects and relationships to blackness.

Pure, Very, New is open through February 16 at Marianne Boesky Gallery.