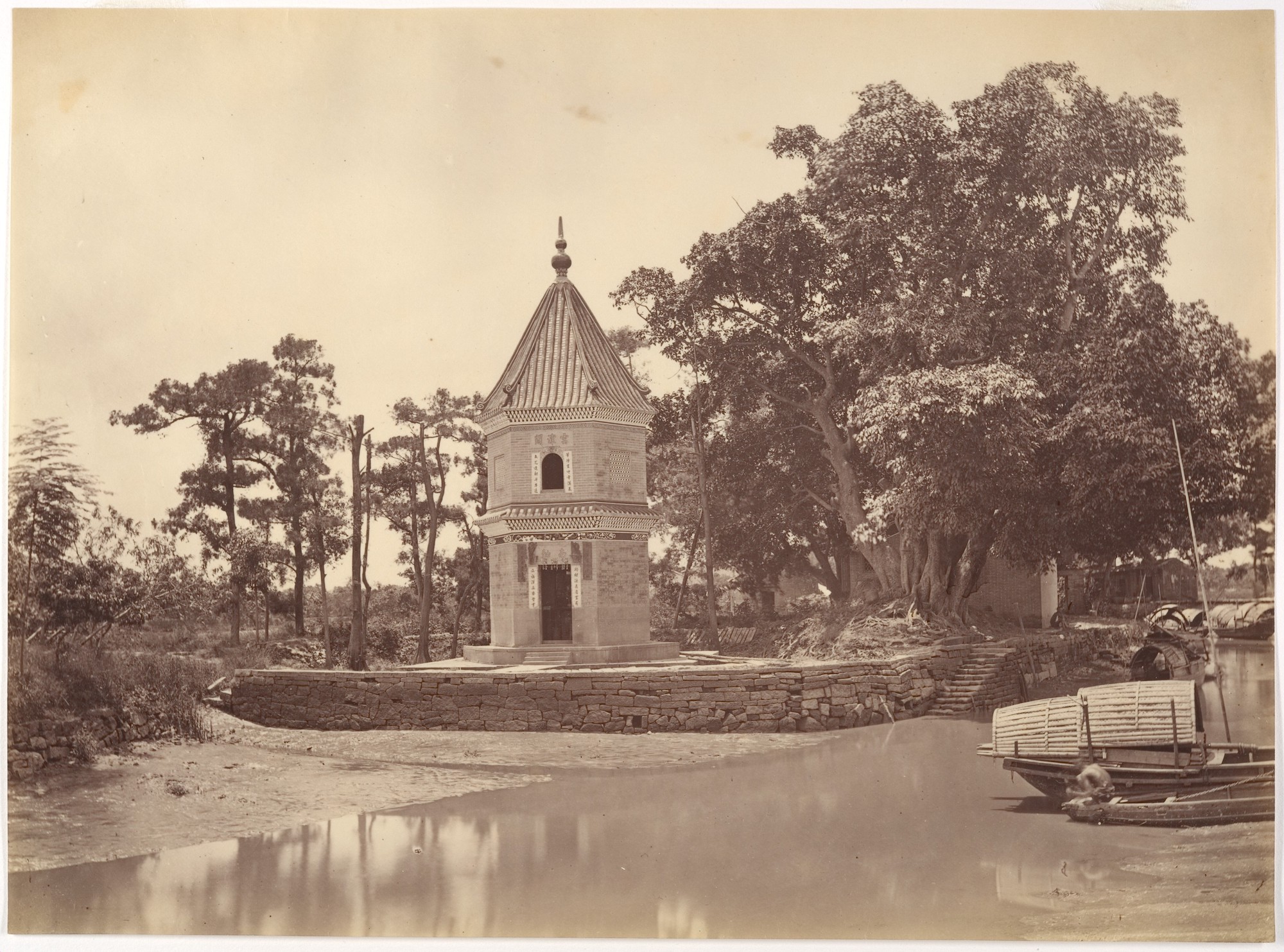

John Thomson, Garden at the English Consulate, Canton, circa 1869, albumen silver print from glass negative, 8.25 x 10.8125 inches [via Wikimedia Commons and The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The American Garden in Nineteenth-Century Canton

Share:

“The enterprising American cultivator … leaves nothing untried which human industry and skill can possibly accomplish. Whether in the simple operations of agriculture or in the varieties which horticulture presents he is at home, and nothing is left untried by which he can advance the importance of his country, and elevate her to the estimation of mankind.”

—“Dispatch from Washington,” Canton Press, 18351

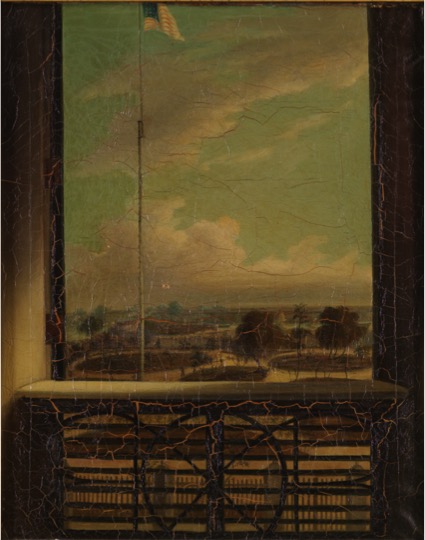

In the 1840s, an unknown Chinese artist painted a picture of the American Garden in Canton from a curious perspective: viewed through a window positioned above it.3 Titled View of the American Garden at Canton from Inside One of the Hongs, the picture is a so-called export painting, produced in Canton for sale in foreign markets.4 It is composed in oil on canvas and employs recognizably European pictorial conventions, perhaps most prominently in its composition as a view through a window, a motif and perspective common to 19th-century romantic painting.5 The garden’s circular planted beds and manicured flora are visible beyond the window’s prominent ledge. The plantings are presided over by an American flag atop a pole so tall that the uppermost part of the flag is cut off by the top edge of the painting. Dominating the foreground, the window’s latticework takes up nearly a third of the entire image; almost half of the garden is visible only through the structure of the window itself. Toward the lower edge of the painting, a fence surrounding the garden further impedes the view by intersecting the lattice and transforming the base of the picture into an almost abstract grid. In the background, ships are visible on the Pearl River, a sketch of trade and commerce at the busy heart of a port city.

Unknown Chinese artist, View of the American garden at Canton from inside of the hongs, mid-19th century, oil on canvas, 26 x 21 x 2 inches [photo: University of Tokyo; courtesy of ©Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, Gift of the Estate of Cassndra K. Dexter Colburn, and Kimia Shahi]

As depicted in this painting, the American Garden is a site of mobility and rootedness, representation and spectatorship, shaped by the commercial conditions and artistic paradigms of the United States’ trade with China. What was the significance of cultivating an “American” garden in the port city of Canton? What insights emerge from considering the American Garden’s material history alongside the stylistically hybrid and commercially collaborative images produced in export art? An analogy between the American Garden and images of it enables a more nuanced consideration of how both subject and representation inhabited the same historical intersections of trade, translation, and ideological negotiation. To look at the American Garden through the shifting historical prism of what art historian Vimalin Rujivacharakul characterizes as “Chineseness and objects, cultural identity and materiality, and geopolitical body and thingness,”6 is to provide a more complicated and interconnected picture of a site shaped by the circulation of both pictures and plants. Such a perspective more fully imagines the political, aesthetic, and botanical stakes of an “American” landscape transplanted into China, and in so doing reveals more about what Rujivacharakul calls the “geocultural texture” of the grounds on which the two met.7

Gardens have a rich history as sites of cultural exchange and encounter. Bound to a specific time and place, they are social spaces, expressive of common experiences that hold “traces of the tensions and energies” that flow through societies.8 Rooted in both science and art, gardens can be simultaneously utilitarian, ideological, experimental, and ornamental. In the context of European and American exchange with China in the 19th century, gardens were part of what historian Fa-ti Fan describes as “networks of information” that linked together trade and the study of natural history.9 In British Naturalists in Qing China: Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter, Fan explains how a growing European fascination with China’s plants and gardens was fed by botanical and horticultural motifs on imported Chinese furniture and artworks. As the aesthetics of Chinese gardens influenced American and European gardeners, trade stimulated a growing interest in Chinese “horticulture and garden plants.”10 In the 19th century the study of horticulture occupied a central place in both European and American scientific endeavors, and plant specimens often moved via the same transoceanic routes as consumer goods. “As with export art,” Fan writes, “plants were exotic goods.” Like export paintings, porcelain, and furniture, increasing quantities of Chinese tea, flowers, and ornamental trees were in high demand overseas, where they were valued for their curiosity and luxury appeal. Foreign horticulturalists even enlisted the services of Chinese painters, who produced botanical illustrations that “bore the visual signature of Chinese export painting”11: its distinctive blend of European and Chinese visual traditions.

Like all aspects of Western trade, however, foreigners’ ability to access Chinese flora was highly restricted. Well into the middle of the 19th century, neither China’s gardens nor its hinterlands were open to foreign plant collectors, who had to rely on Chinese-run nurseries established for the express purpose of distributing native plants to foreigners. The most famous of these nurseries were the Fa-tee gardens, a popular destination for American and European visitors to Canton, whether professional botanists or not.12 Through their presence at Fa-tee, numerous Chinese plants made their way into British and American gardens. And in Canton, to a lesser extent, some Western plants, probably brought to China for use in Western gardens, found their way into Chinese gardens.13

The setting for a complex commercial imbrication of plants and things played out in view of the world, 19th-century Canton was a particularly potent location in which to plant a garden under a foreign flag. It is somewhat ironic that a war fought over the illegal trade in opium, a drug produced from the poppy plant, would form the backdrop for the sowing of the American Garden. Although American traders had smuggled the drug into Canton as rapaciously as the British, the United Sates would remain avowedly neutral during the First Opium War, also known as the Anglo-Chinese War. The Treaty of Nanking ended the war in 1842, opening additional Chinese ports to foreign trade and ceding Hong Kong to Great Britain. By midcentury, however, the United States had surpassed Britain and other European nations to become the leading commercial presence in China.14 The American Garden came to be at the start of this transformative period, which heralded significant shifts in the kinds of mobility afforded to Europeans and Americans in China.

Commonly known as Respondentia Walk or the Square, the original site of the American Garden was located outside a group of buildings called “factories,” or “hongs,” which were the designated headquarters for foreign merchants in Canton.15 These “Thirteen Factories” occupied a stretch of about a thousand feet along Canton’s waterfront that was kept separate from the rest of the city. From 1757 until the First Opium War ended, this small area was the only sanctioned zone of European and American trade in Mainland China, after which period four additional “Treaty Ports” opened along the coast.16 In the decades before the war, the Square had served as an open thoroughfare, something like a public plaza, where locals and foreigners mixed. As art historian Johnathan Farris has described it, though, the Square was “transformed by cross-cultural conflict” while tensions grew between the Chinese and the British over the illegal smuggling of opium into Canton, a practice that directly or indirectly involved or implicated most of the foreign mercantile community. Faced with increasing tension and confrontation on the streets of Canton, the foreign merchants would ultimately enclose the square as a security measure, prohibiting any Chinese people from entering. By the close of the war, what Farris calls a newly “fortified environment”17 had become the American Garden, a space “created as much to control Chinese traffic as to provide recreational space for the Americans and Europeans.”

John Thomson, Garden at the English Consulate, Canton, circa 1869, albumen silver print from glass negative, 8.25 x 10.8125 inches [via Wikimedia Commons and The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Born out of a conflict that added new borders to an already highly controlled urban space, the American Garden began as a site defined by exclusion. Contemporary accounts of the garden describe a pleasant and “agreeable” place, frequented by Americans and Europeans who strolled through grounds “arranged with walks and ornamented with shrubbery and flowering plants, presenting a delightful resort in the freshness of the morning and the cool of the evening.”18 As park-like as it seemed, however, the garden was also the only place where Americans and Europeans could freely “[take] air and exercise” within the small zone to which their movements were restricted in Canton.19 It would serve this purpose for less than two decades, perishing in an 1856 fire during the Second Opium War, which also destroyed the European and American hongs.20

The few firsthand descriptions of the American Garden that exist are tantalizingly vague, but one of the most interesting things they reveal is that the garden nonetheless seems to have been a place that was observed a great deal, both by the foreigners inside and by the Chinese kept out by its fences. According to some British and American diarists, the garden was apparently “one of the most interesting sights” for Chinese visitors to Canton.21 One 1855 account describes the scene:

They squat in rows along the sides of the quays, smoking their pipes and fanning themselves, contemplating all the while with a satirical and contemptuous eye the English and Americans who promenade up and down from one end to the other, keeping time with admirable precision.22

There do not appear to exist any Chinese writings that describe the garden, which means that this essay is restricted to a limited account of its impact on the social topography of Canton.23 Even so, it remains significant that Anglophone writers noticed, and noted, the pastime of observing “the Westerners promenading in their cage,” and described it as something of a common activity for the denizens of Canton.24 As Paul S. Forbes took the time to describe in an 1843 diary entry, “when walking inside [the garden] you can see outside.” This phrase suggests that people inside the enclosure were aware they were being watched, and they turned their gazes outward to look back at the spectators. Forbes later describes an incident in which this game of mutual observation escalated into a physical confrontation: a group of “humble Chinese looking through the rails with respect” became the target of suspicion from individuals inside the fences, to the extent that when a group gathered to peer through the garden’s gate, people inside felt their “dignity compromised by the simple curiosity of the Chinamen” and “slammed [the garden’s gate] in their faces.”25

It is fitting that a site at which the act of looking was so highly charged was reproduced in so many images during its brief existence. More so than in textual records,, the American Garden’s development and appearance can be partially documented in numerous export artworks, including “hong paintings,” a category of export art that featured views of the foreign factories as seen from the water. As the American Garden was coming into being, it occupied a central place in these views, forming part of a class of image that, according to art historian Patrick Conner, served as “the essential and symbolic Western image of the China Trade.” Views of this type chart the garden’s history, from its inception as a fenced-in square, to the beginning of initial plantings, to its final composition. They do so in what Conner characterizes as “a recognizably Western idiom [that retains] certain Chinese aspects,” combining, for instance, European “principles of perspective” with an “overall sharpness of detail.”26 As export artworks, hong paintings were images built to move. Their makers combined Chinese and European visual idioms to create visibly hybrid pictures that would reference their foreign origins once they crossed the ocean and were hung in an American or European dining room. As stylistic (and stylish) records of cross-cultural encounter, these objects were fully activated only by processes of spectatorship and of display, a dynamic that also inflected the American Garden itself.

Unknown Chinese artist, View of the American Garden at Canton, 1844-1845, ink and gouache on paper, 18 x 22 x 1 inches [photo: Mark Sexton; courtesy of ©Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, and Kimia Shahi]

View of the American Garden, a paradigmatic hong painting, presents a particularly striking view into the garden. Rendered in minute detail, circular and rectangular planting beds contain a large variety of trees and shrubs. Leisurely groups of pedestrians meander along smooth and curvilinear walks. Ringed by colorful flowers in the ornate center plot, the familiar flagpole towers in the middle. The garden is surrounded by tall fences, which are buttressed by a regularly spaced row of trees that lines the inner perimeter like a second fence. Bounded by tall buildings with blank windows on two sides, the garden abuts broad thoroughfares to the left and right; various figures walk or stand along these roads. In the immediate foreground, numerous small boats populate a busy waterway, which connects directly to the garden via a couple of staircases that descend directly to the river. If the American Garden’s high fence was a barrier, it also served as a site of encounter and a frame for the exchange of gazes into and out of the space. View of the American Garden can be productively interpreted in terms of an analogous problematic of vision, access, and point of view. Although the painting’s level of detail may suggest that this image was created at least partly from close observation, it is shown from a semi-aerial perspective, and from what appears to have been a fictional or, at least, highly implausible vantage point.27 This aspect suggests that the image is imaginative to some degree. To this point, one feature of the composition is especially peculiar: nearly half of the gates to the garden hang open, most prominently in the waterfront foreground. Outside the centermost gate, three boats angle themselves toward the garden, almost as if they intend to enter. In one boat, two figures even stand upright, as if to disembark. These open gates depict the garden as far more permeable than that it was intended to be, directly conflicting with period descriptions like those cited previously in this essay. As if to amplify the open gates’ suggestion of access and entry, the picture’s elevated perspective affords a panoptical, even cartographic view into the garden.28 On one hand, these pictorial liberties can be understood as part of an artist’s generally idealized or slightly fanciful representation of the garden. On the other, they might also subvert the garden’s identity as an enclosure altogether by suggesting its vulnerability to possible incursion by intruders. If in real life Chinese spectators threatened to violate the sanctity of the garden’s boundaries simply in the act of beholding, the artist’s indexing of a “Chinese” hand and eye in combination with “Western” stylistic conventions destabilizes the identity of the garden’s implied beholder, similarly to the way the painting itself is formally destabilized and physically mobilized as an export painting caught between two stylistic vocabularies.

Writing to his wife, Rebecca, in 1843, merchant Nathaniel Kinsman described the American Garden as:

A great improvement, and great credit is due to those who designed the plan and to Mr. Bull who devoted his time to oversee and complete the work of laying out the ground, ornamenting etc. It is literally Yankee Square, for the English who did very little towards it, seldom avail of the place to promenade.29

As Kinsman mentions, the man responsible for planning and planting the American Garden was Isaac Miles Bull, a Connecticut-born merchant who had moved to Canton in 1833 and stayed until 1847. Although Bull was praised for his “skill and taste” in implementing the garden’s design, the specifics of his plans for the American Garden are unknown today. There does not appear to be any period documentation of his designs, nor do any extant sources record the species of the trees, flowers, and shrubs that were planted. In 1843 botanist Robert Fortune, of London’s Royal Horticultural Society, noted that the American Garden contained “numerous shrubs and trees indigenous to the country.”30 Notably, Fortune’s use of the word “indigenous” does not specify a country of origin. South Carolinian Louis Manigault visited the garden and wrote of seeing “numerous rare plants from Java, India, and other countries. Here are banana trees, cassia, and many others …. The American Garden alone cost $3,000.”31 Following Fortune and Manigault’s accounts, it is probably reasonable to assume that the American Garden included a mix of plant species of varying, even multiple origins.

If the American Garden did contain a global array of plants, it would be in keeping with American national horticultural and cultural values of its time. In October 1835, a “Dispatch from Washington” was published in the local English-language Canton Press. This dispatch proclaimed the industry and skill of “The enterprising American cultivator,” who made himself “at home” in all the “varieties which horticulture presents,” in order to “advance the importance of his country.” As the dispatch suggests, in the wake of American independence, gardening had become something of a patriotic duty. According to Thomas Jefferson’s maxim, “the greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to it’s [sic] culture,” and for 19th–century American botanists, the acquisition and culture of new and exotic plant species was a means of articulating national identity and establishing what historian Philip Pauly calls “horticultural independence” through gardens that affirmed America’s place in transoceanic trade networks.32 But the question of which plants were indigenous and which were exotic was not so straightforward for American gardeners like Isaac Bull. America’s was a landscape that had already been significantly shaped by colonial practices of transplanting, hybridizing, and replacing native and non-native species, including ones from Europe, Africa, and Asia. Eighteenth-century Anglo-American scientists had even noticed that a number of “rich and valuable”33 Chinese plants grew wildly in North America, which was thought to share a similar climate. America also possessed, in large quantities, one of the only natural resources that “Chinese merchants would accept in exchange for their goods”: ginseng.34 These revelations motivated botanists to explore the possibilities of transplanting Chinese species to America, even to seek the discovery of more potentially “‘native’ American analogies of Asian plants such as tea.”35

John Thomson, A Garden in Canton, circa 1869, albumen silver print from glass negative, 8.4375 x 10.875 inches [via Wikimedia Commons and The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Just as the cultivation and study of foreign plants played a vital role in America’s burgeoning horticultural nationalism, popular landscape architecture of the 1830s also emphasized the aesthetic importance of including exotics in well-designed gardens. The most prominent of them was known as the “gardenesque” style, a term coined by popular Scottish landscape architect John Claudius Loudon, author of the highly influential Encyclopaedia of Gardening, first published in 1824.36 Loudon, a prolific writer on garden design, encouraged planting schemes that showcased “rare and exotic specimen plants and trees,”37 and were arranged according to a “natural system” that grouped plants based on formal similarities and botanical classifications, dividing native and non-native species and emphasizing a quasi-taxonomic but highly aestheticized combination of horticultural science and sensuous design.

Observing View of the American Garden again, it is evident that gardenesque elements are present in its layout. For instance, the beds are arranged in curving, slightly irregular forms and include “elaborate color schemes” of planted annuals. Lawns are speckled “with potted exotics and urns” of flowers. The garden’s “trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants [are also] separated”38 from one another in agreement with Loudon’s schema. Although straight and irregular plantings are both visible, it is unclear how the division between native and exotic plants would have been articulated in such a culturally hybrid context. Some plantings also appear to be grouped according to formal or botanical properties, such as the prominent cluster of palms toward the right side of the picture. Loudon emphasized that every aspect of a garden must contribute to the aesthetic experience of natural beauty, including “the smooth surfaces, curved directions, a dryness and firmness of gravel walks.”39 The garden’s tightly controlled aesthetic sensibility is especially close to Loudon’s principles, in that if any horticultural logic is present, it is subsumed by what Loudon termed the most important element of gardenesque design, that is, “displaying the art of the gardener.”40 As the painting itself attests, Loudon’s garden designs seem particularly predisposed to an artistic afterlife.

Landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing was responsible for popularizing Loudon’s principles on American soil. In A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841), he advocated for American gardeners to, in his words, introduce “exotic ornamental trees, shrubs, and plants, instead of those of indigenous growth.”41 Contradictorily, however, Downing also emphasized the patriotic necessity of cultivating gardens as a way of more firmly connecting Americans to their own land. He felt that the restless, westward-moving American of the early 19th century was “unable to take root anywhere, he leads, socially and physically, the uncertain life of a tree transplanted from place to place, and shifted to a different soil every season.”42 Similar to Jefferson before him, Downing’s nationalistic appeal to Americans to “take root” paradoxically hinged on the idea that a good portion of those roots should arrive via circuitous overseas paths.43 While both Loudon and Downing praised many Chinese plants for their agreeability to English and American gardens, however, neither author was particularly invested in the aesthetics of Chinese gardens themselves, preferring to stick to European vocabularies of horticultural order and gardenesque display. Whereas Downing noted that Chinese-style architecture was “wanting in fitness” and unsuitable for the American “domestic” context,44 Loudon’s opinion was more disparaging; although he praised Chinese ornamental plants, he maintained that “it is our [Europeans’] excellence to improve nature; that of a Chinese gardener to conquer her.”45

Patrick Conner writes of View of the American Garden that, “except perhaps for the palms which occupy one of the planted areas [at far left], the scene presented here might as well be a park newly laid out in Europe or North America.”46 Conner observes that there are far more women and children present in the park than probably would have occupied the factories at the time, since it was only after war that foreign women were even allowed to enter Canton.47 The figures within the garden appear to be enjoying the sights; many of them gesture conversationally at the trees and plants. Far from security or surveillance, this scene communicates a sense of order, stability and fecundity, both botanical and human. This type of association between gardens and domesticity had served as a flashpoint in the years leading up to war between Britain and China. In the aftermath of an 1822 fire in the hongs, a small and informal garden had been set up in front of the British East India Company’s factory. An oblong enclosure, the so-called English Garden apparently provoked protest among Canton’s Chinese residents, probably in part because, as an extension of the foreign space of the factory, it was viewed as also extending foreign power into a previously unrestricted space.48 In this sense, the English Garden sent the worrying signal that a group of transient traders might be planning to put down permanent roots. Such roots would certainly have gone against the prevailing Imperial opinion that the British and the Chinese were fundamentally and inherently incompatible, as Ch’ien Lung, fourth Qing emperor of China, had famously expressed in a 1795 mandate to King George III of Great Britain, through the apt use of botanical metaphor:

Though you assert that your reverence for our Celestial dynasty fills you with a desire to acquire our civilization, our ceremonies and code of laws differ so completely from your own that … you could not possibly transplant our manners and customs to your alien soil.49

The suspicion that a reversal of this transplantation might take place was only reinforced in 1830, when three British and American women were caught attempting to enter Canton, violating the strict ban on Western women (and, thus, families) within the city. A decade later, as the American Garden was being completed, foreign women would for the first time be permitted to live in Canton. The Americans, it seemed, were then in a position to put down roots of their own.

More than just an agricultural endeavor, American garden culture played a large part in patriotic efforts to develop what Kariann Akemi Yokota calls a “vocabulary of material independence,” through the establishment of a system of trade with China.50 Just as it had had as a colony, the new American republic had an appetite for Chinese goods; tea and export art were foremost among them. As Yokota explains, conspicuous consumption of Chinese things would play a central role in American expressions of national identity on the global stage. The first United States ship had sailed for Canton in 1784, bringing with it a sizable cargo of ginseng. The Americans would quickly establish a thriving transoceanic trade with China, in part because of their famously fast clipper ships and use of Pacific trade routes, and also thanks to their comparative abundance of natural goods that were prized by the Chinese, with which Americans could acquire Chinese export ware and luxury items—“refined goods to adorn their natural habitat.”51

Thus, although export goods and plants were already closely interconnected in China’s trade with the West, it can be argued that these interconnections were particularly strong in the case of America. Ironically, as Americans sought to rival the British in their consumption of Chinese luxury goods and curiosities, they would exploit the affinities between their natural landscape and that of China, selling ginseng, sandalwood, and furs that were highly valued.52 They also demonstrated these affinities to the Chinese as a way of emphasizing their political power. In an 1843 letter of greeting to Daoguang, sixth Qing emperor of China, US President John Tyler employed this tactic yet, proclaiming:

The twenty-six United States are as large as China, though our people are not so numerous. The rising sun looks upon the great mountains and great rivers of China. When he sets, he looks upon rivers and mountains equally large in the United States. Our territories extend from one great ocean to the other, and on the west we are divided from your dominions only by the sea.53

Based on the prominence of the American landscape and American biota in both its political and commercial discourses with China, it is particularly interesting to consider once more the presence of the American Garden as an image in export art. On the most basic level, these images represent an “American” landscape transplanted into China. However, they also participate in a broader history of Sino-American cross-pollination, adding yet another layer of cultural synthesis to images whose stylistic rhetoric was meant to evoke what Conner calls “a distant and mysteriously alien culture.”54 If, as Wade Graham has eloquently stated, “anyone who creates a garden draws a map of their mind on the ground,”55 what is created when that garden acquires an independent life as an image?

John Thomson, Garden, Canton, circa 1869, albumen silver print from glass negative, 8.125 x 11.125 inches [via Wikimedia Commons and The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Returning to View of the American Garden at Canton from Inside One of the Hongs helps excavate the implications of this question. The painting probably depicts a view through a window in the Imperial hong, a factory owned by the merchant Howqua, who rented it to a number of businesses, including the American firm Wetmore & Co. The Imperial hong had also the part-time residence of the British painter George Chinnery.56 Although Chinnery rented his upstairs rooms well before the American Garden was laid out, a distinctively angled view such as the one through the window was a rare and unconventional perspective used in export paintings, a type partly attributed to Chinnery’s influence.57 In contrast with View of the American Garden, this more picturesque style of composition embodies the viewing position of a Western subject, a position that is affirmed in the view’s literal framing, through the window, as from within one of the factories. The stark differences between View of the American Garden at Canton from Inside One of the Hongs and View of the American Garden offer differing analytical lenses through which to view the garden itself. Such images inform our perception of the American Garden as a place that participated in the complex currents of transoceanic trade, as well as the myriad material networks out of which the garden was conceived.

This interpretation of the American Garden is both historical and “etiological.” In her 1979 article “Grids,” art historian Rosalind Krauss defines etiology as a mode of thinking both alongside and around more straightforward or historically linear narratives of cause and effect, in order to understand something as part of a thicker grid of interrelated conditions.58 Such an approach is particularly useful in a study like this one, where gaps in archival information call for broader and more speculative registers of interpretation alongside close attention to period texts and objects. In the same article, Krauss also discusses the motif of the view through the window in 19th–century painting. Krauss argues that the window’s frame and bars anticipate modernism’s formalist grid, a reflexive representation of the painting’s own organizing structure, mapped back “onto itself.” At the same time, this window-grid also “operates from the work of art outward, compelling our acknowledgement of a world beyond the frame,” much like the actual experience of looking out a window.59 View of the American Garden at Canton from Inside One of the Hongs operates similarly: as an export painting, it is a formally self-conscious image, only ever European or Chinese enough so that each trait is recognizable. It is a picture that is neither here nor there, in much the same way as can be said of its subject, a landscape that has been configured by the apparatus of Sino-American trade, as well as the violence of the Opium War. Like the Chinese observers who peered through the garden’s fences, the Americans who looked out at them as they promenaded in Yankee Square, or the merchants who purchased export artworks to carry home across the ocean, any attempt at a historically complete picture of the American Garden remains elusive, even as it refracts outward, toward a number of intersecting contexts. It is glimpsed as if through a window, its frame “arbitrarily truncating our view but never shaking our certainty that the landscape continues beyond the limits of what we can, at that moment, see.”60

Kimia Shahi is a PhD candidate in art and archaeology at Princeton University. Her research investigates modes of picturing the ocean and sea coasts in the 19th-century United States. Forthcoming publications include contributions to Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment (2018), and For America: The Art of the National Academy (2019). Shahi is currently the 2018–2019 Wyeth Foundation Pre-Doctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

*this text and bio was originally written and published in our Summer 2018 issue, 42.02 Ports of Call

References

| ↑1 | “Dispatch from Washington from May 21, 1835,” Canton Press 5, October 10, 1835: 36. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Wade Graham, American Eden: From Monticello to Central Park to Our Backyards: What Our Gardens Tell Us About Who We Are (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), xiv. |

| ↑3 | Patrick Conner, The Hongs of Canton: Western Merchants in South China 1700–1900, as Seen in Chinese Export Paintings (London: English Art Books, 2009), 190. Conner includes an image of this view and calls it “unusual.” |

| ↑4 | Conner, The Hongs of Canton, 1. Conner defines “Chinese ‘export painting’” as work “intended solely for foreign markets, produced in Canton in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” |

| ↑5 | Lorenz Eitner, “The Open Window and the Storm-Tossed Boat: An Essay in the Iconography of Romanticism,” The Art Bulletin 37, no. 4 (December 1955): 285.“The pure window-view is a romantic innovation—neither landscape nor interior, but a curious combination of both.” |

| ↑6 | Vimalin Rujivacharakul, “China and china: An Introduction to Materiality and a History of Collecting,” in Collecting China: The World, China, and a Short History of Collecting, ed. Vimalin Rujivacharakul (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011), 22; 15. |

| ↑7 | Rujivacharakul, “China and china,” 15. |

| ↑8 | Graham, American Eden, xii–xiv. |

| ↑9 | Fa-Ti Fan, British Naturalists in Qing China: Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 3. |

| ↑10 | Fan, British Naturalists in Qing China, 14. |

| ↑11 | Fan, 38; 41. |

| ↑12 | Fan, 29. In his 1818 account of a visit to China, Clarke Abel recounts a visit to the Fa-tee nursery gardens, which he characterizes as the only area in the suburban environs around Canton that was not prohibited to foreign visitors. Abel notes a large variety of plants, many chosen for their visual appeal rather than their rarity. See: Clarke Abel, “Nursery Gardens,” 220–221 in Chapter VIII, Narrative of a Journey in the Interior of China and of a Voyage to and from that Country, in the Years 1816 and 1817, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1818. Abel was a member of the Geological Society of London, as well as Chief Medical Officer and Naturalist to the Embassy. |

| ↑13 | Fan, 35. Fan notes that these Western plants were probably “appreciated for their beauty, novelty, or utility” by Chinese consumers. |

| ↑14 | Kariann Akemi Yokota, Unbecoming British: how revolutionary America became a postcolonial nation, (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 151–152 |

| ↑15 | Conner, 100–101. Many sources confirm the interchangeable use of these names. Conner notes that the name Respondentia was in reference to a Respondentia Walk located near the Hooghly River in Calcutta, India. “A ‘respondentia bond’ was a loan for which cargo was named as security,” a common practice. Although today the word factory designates a building or group of buildings used for the manufacture of products, historically the word more typically referred to an establishment for merchants doing business in a foreign country. Webster’s American Dictionary of 1828, for example, defines the word in the following way: “noun. 1. A house or place where factors reside, to transact business for their employers. The English merchants have factories in the East Indies, Turkey, Portugal, Hamburg, etc.; 2. The body of factors in any place; as a chaplain to a British factory; 3. Contracted from manufactory, a building or collection of buildings, appropriated to the manufacture of goods; the place where workmen are employed in fabricating goods, wares, or utensils.” (Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, New York: S. Converse, 1828), 718. Nineteenth-century sources thus referred to Canton’s foreign hongs as “factories,” since they represented business interests for those profiting from the import and export of goods. Kariann Yokota observes that: “In Chinese, the terms ‘hong’ and ‘factory’ are interchangeable, if not identical, because factories included dwellings and offices. Hongs were strictly places of business … the word ‘factory’ was in this context synonymous with ‘agency’ rather than ‘manufactory.’” (Yokota, 135). |

| ↑16 | Stanley Lane-Poole, The Life of Sir Harry Parkes: Vol. 1 (Consul in China), (Wilmington, DE: 1973) (originally published, London/New York: Macmillan, 1894), 163. |

| ↑17 | Johnathan Farris, “Thirteen Factories of Canton: An Architecture of Sino-Western Collaboration and Confrontation.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 14 (Fall 2007): 78–80. Farris also notes that the garden’s size and format shifted in response to local happenings; for instance, after an 1846 riot it was apparently expanded, and new plantings added. Although its approximate date of completion is agreed upon by all scholarship I have consulted on the garden’s history (and images of the garden also support these dates), it is unclear exactly when the garden was initially planned, as well as the precise date(s) it was completed. |

| ↑18 | Harry Parkes, letter of October 27, 1842, quoted in “Parkes’ description of life at Canton,” in Lane-Poole, Life of Sir Harry Parkes, 168–169. Conner also quotes this letter, 187. Conner, 193, quoting Frances Hawks’ Narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China Seas and Japan: performed in the years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States Navy, by order of the government of the United States, Washington, D.C.: A.O.P, Nicholson, vol. 1 (1856), 136. |

| ↑19 | Parkes to Mrs. Lockhart, March 29, 1852, in “Parkes’ description of life at Canton,” in Lane-Poole, Life of Sir Harry Parkes, 168. |

| ↑20 | Farris 2007, 80. The destroyed foreign hongs were rebuilt on neighboring Shamian Island soon thereafter, never to return to the mainland. |

| ↑21 | The American Garden was definitely an attraction for the Chinese, but the idea that it was “one of the most interesting sights” in Canton was an inaccurate one. The foreigners were not allowed to leave their enclave and never realized that Canton had old temples, pagodas, the oldest mosque in southern China, etc. I thank Esther da Costa Meyer for this and many other important insights over the course of this project, which was begun in her seminar “Art in Translation” at Princeton University in fall 2014. |

| ↑22 | Évariste Régis Huc, The Chinese Empire, translated by J. Sinnett (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1859), 336. Quoted in Farris 2007, 78–80. |

| ↑23 | Professor May Bo Ching, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, email to author, January 9, 2015. Over the course of my own research, I have corresponded with noted scholars who study related topics: Professor Fa-ti Fan, of Binghamton University, whose work has proved incredibly useful to this project; Professor May Bo Ching of Zhongshan University in Guangzhou; and Professor Winnie Wong of the University of California, Berkeley. These scholars have not been able to point me toward any readily available source materials in Chinese, and I am limited in my own research by my inability to read Chinese. However, the Chinese side of the story remains a potentially fertile ground for further investigation and future research. |

| ↑24 | Peter C. Perdue. “Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System—III: Canton & Hong Kong” (Cambridge, MA: Visualizing Cultures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009), presented on MIT OpenCourseWare, http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/rise_fall_canton_03/cw_essay03.html |

| ↑25 | Paul S. Forbes, diary of 1843, (entry May 15, 1843), Forbes collection, Doing Business in 19th Century China, Manuscripts Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University. Quoted in Farris, 79. |

| ↑26 | Conner, “Views of the Pearl River: A Developing Art,” in Views of the Pearl River Delta: Macau, Canton and Hong Kong, ed. Gerard Tsang and Dan Monroe (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Museum of Art; Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, 1996), 16–17. |

| ↑27 | Eva Kit Wah Man has noted that it was only “Western painters [who] emphasized outdoor sketching, whereas the export art painters, who worked primarily in studios, are not recorded as having engaged in this activity.” Eva Kit Wah Man, “Influence of Global Aesthetics on Chinese Aesthetics: The Adaptation of Moxie and the Case of Dafen Cun,” Contemporary Aesthetics 11 (November 7, 2013): n.p. |

| ↑28 | Richard Capurso Research Papers, Acc. 2009.029, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. Quoting Canton Press 4, no. 37 (1839), “the enclosure is intended for the use of foreigners, and to keep out the populace.” |

| ↑29 | Nathaniel Kinsman to Rebecca Kinsman, November 28, 1843, Kinsman Family Papers, M55 45 Box 3, Folder 9, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. |

| ↑30 | Conner, 2009, 188. Quoting Robert Fortune, Three Years Wanderings in the Northern Provinces of China, London, 1847, 156. |

| ↑31 | Richard Capurso Research Papers, Acc. 2009.029, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. |

| ↑32 | Philip J. Pauly, Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 2–3. Pauly also notes that this ca. 1800 statement of Jefferson’s was cited frequently over the next century. |

| ↑33 | Pauly, Fruits and Plains, 19. Quoting partly from John Mitchell, “The Present State of Great Britain and North America,” 1767. These plants included mulberry (the food of silkworms), persimmon, and tobacco. |

| ↑34 | Janice L. Neri, “Cultivating Interiors. Philadelphia, China and the Natural World,” in: Amy R.W. Meyers and Lisa L. Ford, eds., Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 196. |

| ↑35 | Pauly, 2007, 20, quoting partly from Charles Thomson, Manifesto to the American Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Philadelphia, 1768. |

| ↑36 | Farris, 78. Farris states that Bull’s design was based on Loudon’s principles but offers no proof of this claim. |

| ↑37 | Graham, American Eden, 70. |

| ↑38 | Ibid. |

| ↑39 | John Claudius Loudon, The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (London, 1838), 161. Quoted also in Therese O’Malley, “Your garden must be a museum to you: Early American botanic gardens,” in: Huntington Library Quarterly 59 (1996) 2/3, 225. |

| ↑40 | Ibid. |

| ↑41 | Andrew Jackson Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (New York & London: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), 35. Quoted in Pauly, 169. |

| ↑42 | Downing, Rural Essays, ed. George William Curtis (New York: George P. Putnam and Company, 1853), 14. Quoted in Graham, 62. |

| ↑43 | James Clifford, “Diasporas,” Cultural Anthropology 9, no. 3 (August 1994): 308. I borrow the phrase from Clifford’s discussion of how “Diaspora discourse articulates, or bends together, both roots and routes ….” Although I appreciate and agree with the ways in which Clifford’s discussion of Diaspora captures the dynamics of mobility versus rootedness, I do not borrow his clever pun with the intent to suggest that the American mercantile community in Canton was a Diaspora as such. |

| ↑44 | Downing, 1841, 344. Quoted in Pauly, 169. Pauly also notes that in 1850s, Downing’s opinions took a much more nativist and racialized turn. Pauly notes the example of Downing’s 1852 characterization of the Chinese Ailanthus as a “Tartar” that, if not watched closely “will beget a new dynasty, and overrun our grounds and gardens ….” |

| ↑45 |

Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening: Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-gardening, Including All the Latest Improvements; a General History of Gardening in All Countries; and a Statistical View of Its Present State with Suggestions for Its Future Progress, in the British Isles (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1826), 108. Quoted in: Craig Clunas, “Nature and ideology in western descriptions of the Chinese gardens,” in: Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident, 22 (2000): 156. This view was new for its time. In the 18th century all European courts and wealthy noblemen had a “Chinese” garden. It is only when the opium trade was established that such negative critiques of the Chinese gardens appear. William Chambers’ book on Chinese architecture had been a primer for the Anglo-Chinese gardens, as was Georges Louis Le Rouge’s Les Jardins Anglo-Chinois (1775–1788). |

| ↑46 | Conner, 189. |

| ↑47 | Ibid; Lane-Poole, Life of Sir Harry Parkes, 163. Lane-Poole quotes the Treaty of Nanking: Article II: “The Emperor of China agrees that British subjects, with their families and establishments, shall be allowed to reside, for the purpose of carrying on their mercantile pursuits, without molestation or restraint, at the cities and towns of Canton, Amoy, Foochowfoo, Ningpo, and Shanghai.” |

| ↑48 | Farris, 77. |

| ↑49 | As quoted in E. Backhouse and J.O.P. Bland, Annals & Memoirs of The Court of Peking (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), 324. Also quoted in Yokota, 135. |

| ↑50 | Yokota, 117. Yokota notes that, in fact, Americans initially brought too much ginseng to China, causing the market to temporarily nose-dive until they learned to moderate the incoming supply. |

| ↑51 | Yokota, 145. |

| ↑52 | See: James R. Fichter, “America’s China and Pacific Trade,” Chapter 8 in So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Trade Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 205–231. |

| ↑53 | President John Tyler, to the Emperor of China, 1843. See: Congressional Series of United States Public Documents, Volume 457 (Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office, 1845), 738. Also quoted in: Chris Elder, ed., China’s treaty ports: half love and half hate: an anthology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 4. |

| ↑54 | Conner, 2009, 2. |

| ↑55 | Graham, xii. |

| ↑56 | Conner, 190, 122–124. |

| ↑57 | Conner, “Views of the Pearl River: A Developing Art,” 1996,18. |

| ↑58 | Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” October 9 (Summer 1979): 64. I thank Carson Chan for advising me to consult this article in connection to my project, and for suggesting that my approach to the American Garden was etiological in this way. |

| ↑59 | Krauss, “Grids,” 60–61 |

| ↑60 | Krauss, 63. |